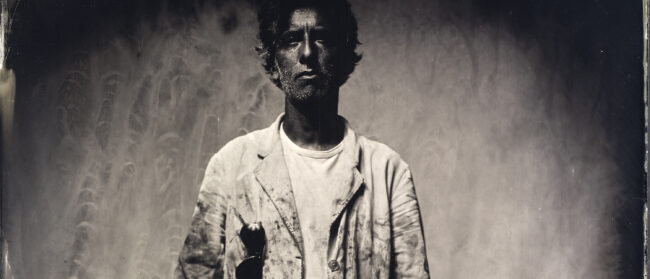

The moment Jeremy Holden stepped onto the tarmac at Phnom Penh International Airport, he knew Cambodia would be home.

For nearly two decades, the freelance conservation photographer has traversed the Kingdom with multiple environmental organisations, including Fauna & Flora International and Wildlife Alliance, to document the species living within its natural landscapes.

The smell of Holden’s black coffee lingered as he downloaded photos from his most recent 25-day expedition into Virachey National Park, one of the most remote protected areas in Cambodia.

He and the rest of the crew never properly left the forest for more than three weeks, Holden said. When they needed supplies, they simply went to the edge of the woods for a coordinated hand-off of goods with some outside helpers.

That deep-rooted approach is part of Holden’s style. A naturalist who refuses to wear chemical sunscreens or insect repellants – he sees them as “kind of cheating” and potentially deadly to the frogs and other small, delicate creatures he often finds – Holden has discovered species previously unknown to science.

That includes a carnivorous pitcher plant that biologists named after him: the Nepenthes holdenii, which grows deep in the Cardamom Mountains. But these findings also include two species of frogs, which hold a special place for Holden.

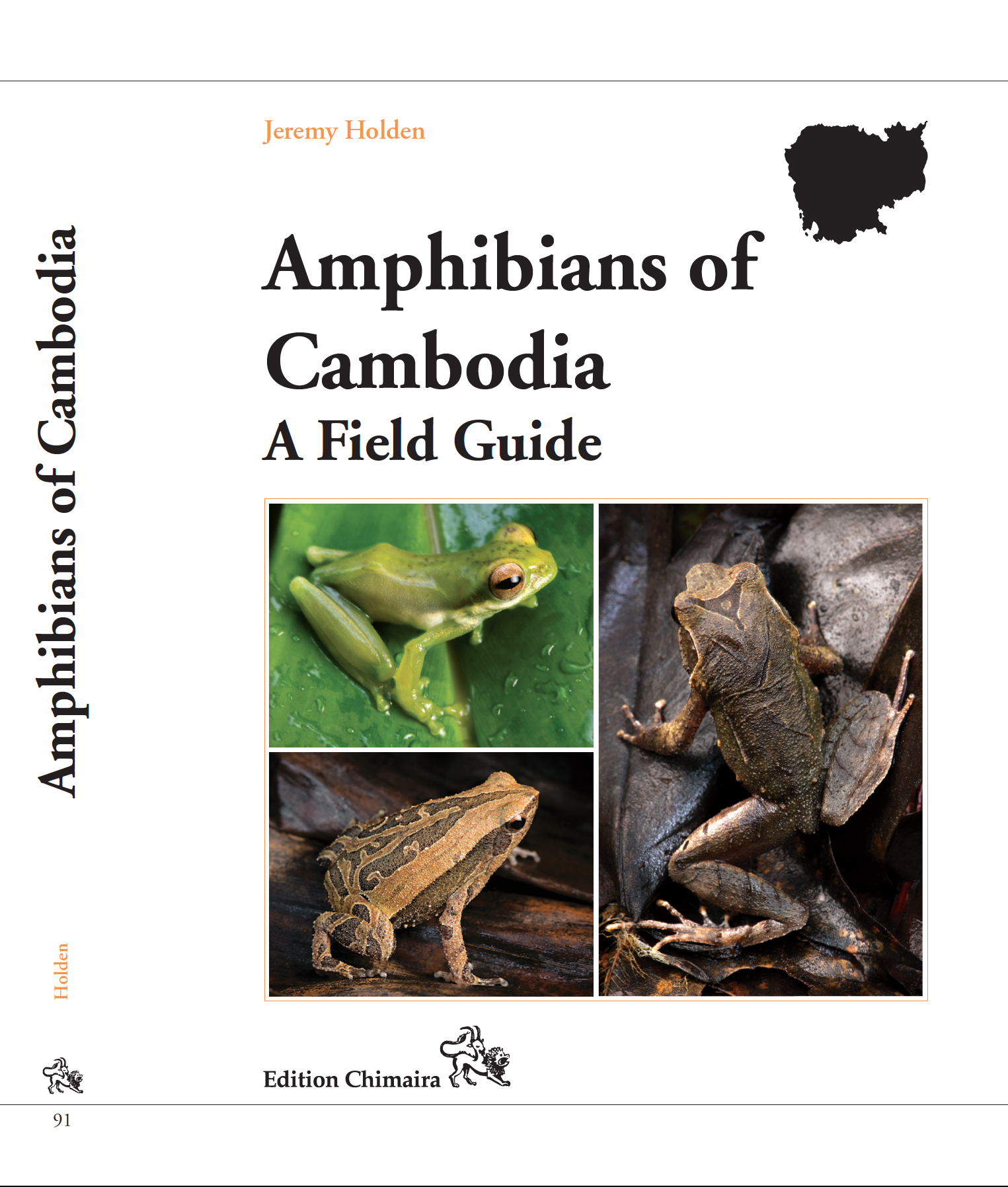

The photographer elaborated on that as he perched in the corner of the second floor of a cafe in Phnom Penh, where he has lived since 2006. His latest major work, a comprehensive field guide to Cambodia’s 75 known frog species, stems from a lifelong interest dating back to his childhood in the U.K.

Since the outbreak of Covid-19, Holden has worked toward documenting these species, many of which are increasingly rare. This guide, Holden’s second on the subject, was just published in Germany last month. But he hopes to bring it to Cambodia, where it might encourage conservation of amphibians in the Kingdom.

Holden sat with the Southeast Asia Globe for a free-roaming conversation on the book and his years of photographing Cambodia.

What was your first memory of Cambodia? And what about the Kingdom made you eventually want to stay?

I always find I know almost immediately as I’m coming down the steps of a plane, whether I like somewhere or not. It’s in the air. And I’m almost never wrong.

When I first came to Cambodia – I had to come down the steps of the plane onto the tarmac at the airport, there wasn’t yet a tunnel through – so I got to smell the country, feel the heat. Immediately, upon arrival here, I knew this is a place I like. I didn’t know why I just knew I liked it. And that has stayed with me.

While having visited Cambodia for the first time in 2001 and several subsequent visits. Holden moved to Phnom Penh in 2006, following nearly a decade in Sumatra, Indonesia. How did you find Cambodia as a photographer?

As a photographer, you have all these prickly senses working when you’re walking in the street. Whether you’re welcome or unwelcome. These are all things that photographers have, you’re very aware.

In Indonesia, it was very difficult to walk the streets and take photographs. One of the reasons I found it so pleasant here is that in Cambodia, when I got to know it a bit better, I saw there was a live-and-let-live attitude. As long as you’re not harming anyone, not being offensive, they just look at you, as if to say, ‘That’s a barang [foreigner], he does barang things’ and it’s accepted.

Walking around and taking photographs, it was suddenly a dream come true. I could do that without being confronted, without people screaming and shouting, they just didn’t care.

When did your passion for frogs begin?

I’ve been interested in frogs since I was four or five years old. My first ever illegal act was to steal a frog from a neighbour’s garden, though I let it go out of guilt. If you go through my old encyclopaedias, there’s little bits of yellow newspaper, on every page that has a frog. So it was a very early interest for me.

But the thing that crystallised that interest here was in 2000, during my first visit to Cambodia when I took part in an expedition into the Cardamom Mountains. I accidentally went to the top of Phnom Samkos and amazingly, because it was dry, I found a small frog, which turned out to be a new species. This connected me to amphibians in Cambodia, because I found a new one.

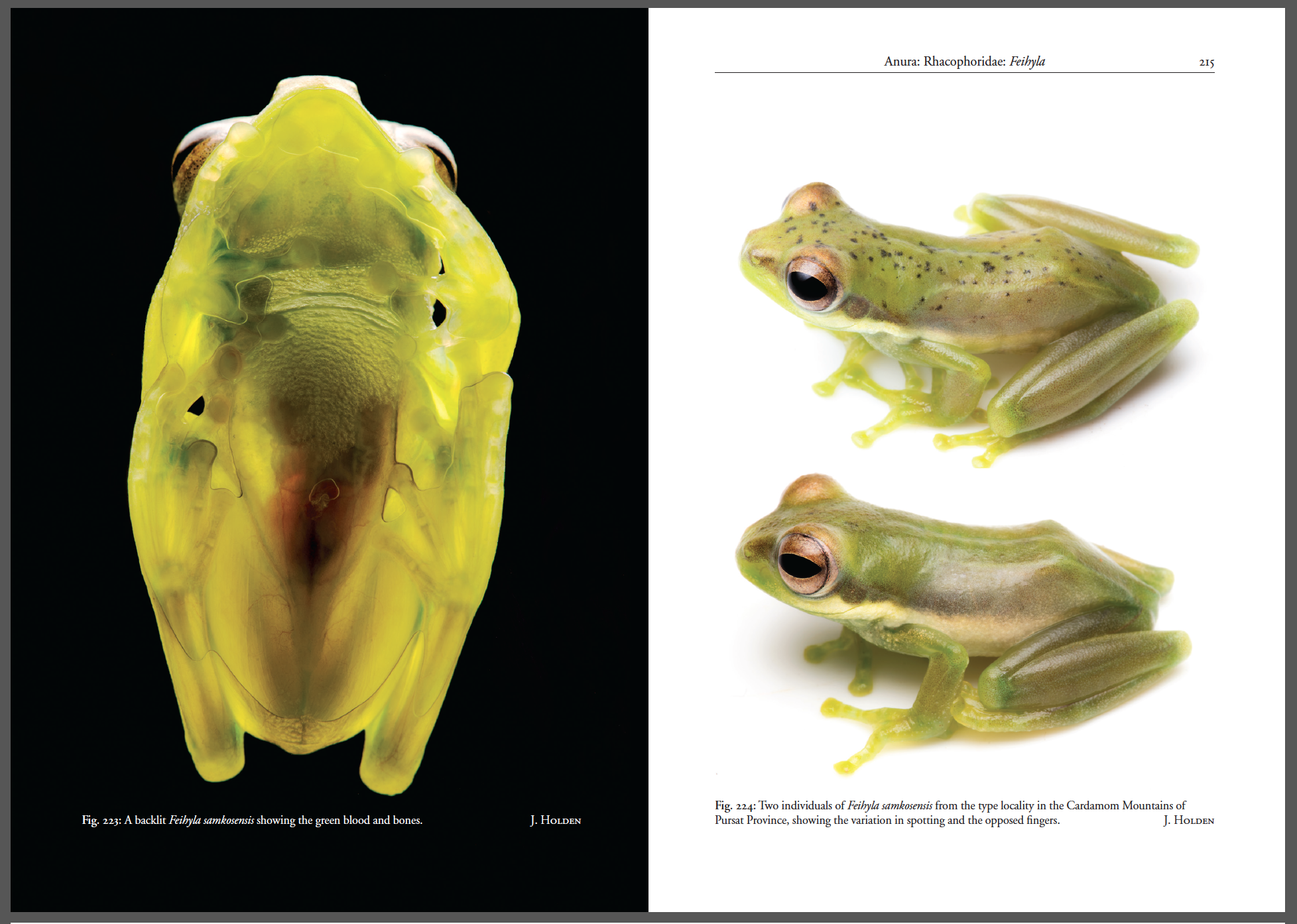

Then in 2007, on the same mountain, I found an incredible tree frog with green blood and blue bones. So that was further kind of making this something that was mine. I was the only one that ever found this.

It’s a lifetime, in the sense of interest and keeping my interest from fading. In a way I’m still the same as I was as a five-year-old in my range of interests. But finding a new species, I’ve got a photograph that no one else has got. Photographers will understand how photographs build upon each other. When you start to get a series your interest piques and you have something to work towards. So a lone photograph might give birth to a whole exhibition, or book in this case.

What were some of the challenges of discovering new species in Cambodia?

The work was in finding somebody that could tell me this was a new species. You still have to find an expert that can prove this is a new species because that’s the easy part, finding it. The description, you have to go through all of the literature to make sure it’s never been found before. It’s never been described before. That’s what takes academic work.

Anybody that goes into the tropical rainforest and spends a little bit of time looking could probably find a new species. Now, to find somebody that can tell you it’s a new species. That’s the challenge.

Why did you feel that there was a need for a frog field guide in Cambodia?

There’s nobody here dedicated to herpetology, this is something I can step into. I’m not a herpetologist. I’m not a scientist. But I can step in. I can take good photographs. I know enough about the frogs that I can produce a book which hopefully isn’t a complete embarrassment and is useful for people.

If there was a herpatologist here that was going to do this work, I would have just helped with photographs, I wouldn’t have done the book myself. This is something nobody else would do, so I did.

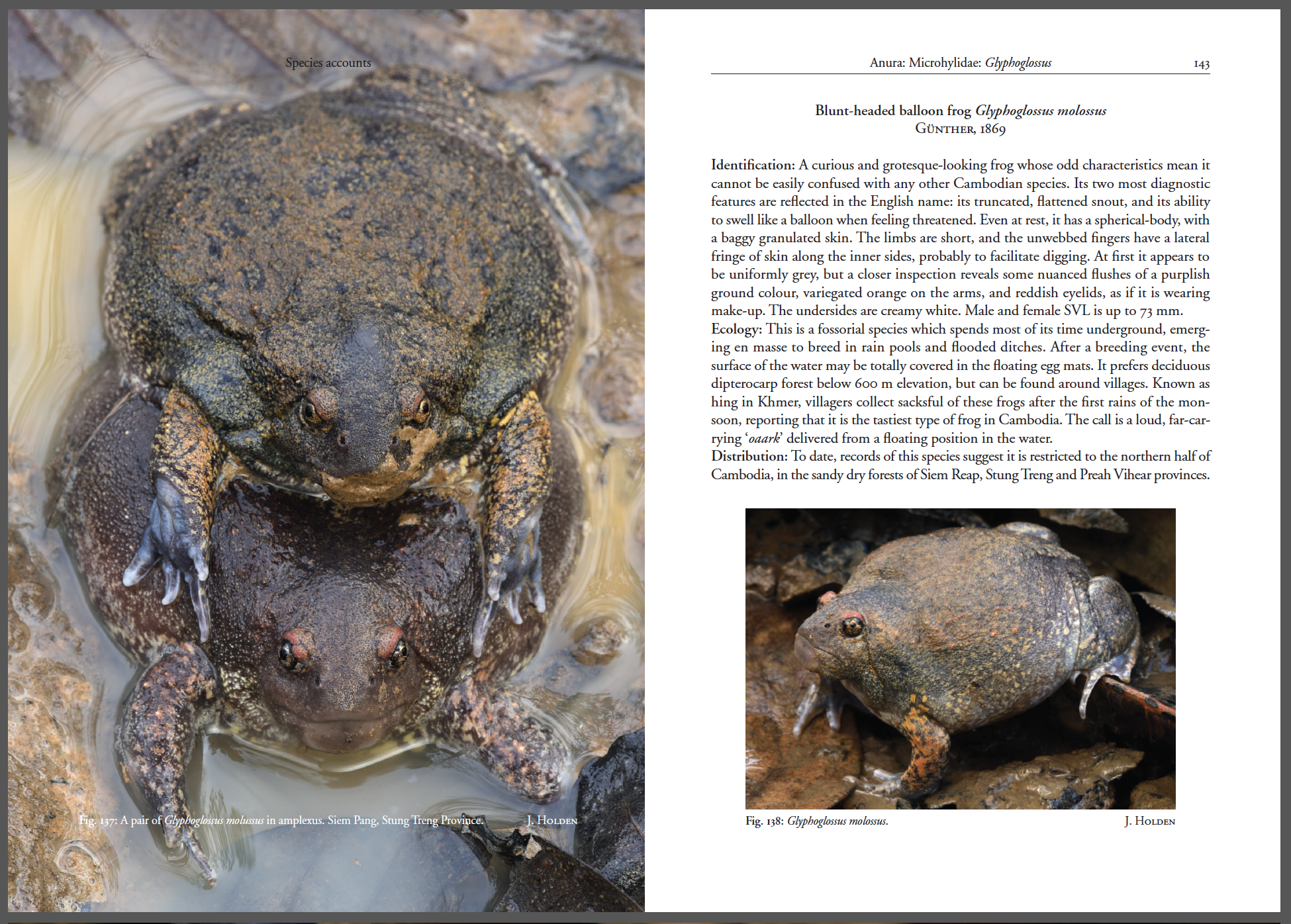

The thing about frogs is that they are a vital component of an ecosystem, they’re in the middle. So much relies upon eating frogs. For instance, Cambodia’s rarest birds – Giant ibis and White-shouldered ibis – both eat an awful lot of frogs. Take away the frogs, and those birds are gone.

While speaking about his expeditions to capture these images of rare frogs, Holden shared that he never wears mosquito repellent or other insecticides. Not only could these chemicals kill the frogs Holden is handling since frogs absorb through their skin, but he also considered them cheating…

This is a covenant that you make when you go into the forest. There’s going to be ticks, there’s going to be leeches, there’s going to be mosquitoes. It’s like a tax. How I look at it is that you are becoming part of the process of the rainforest so you can’t go in in full armour, that’s kind of cheating in a way. So it can be unpleasant and sometimes it’s maddening, but there’s nothing you can do. With that forest tax, in the best way, you’re invited to be part of the process.

Do you have any photojournalism or personal ethics while you’re documenting these frogs?

Respect. Whether it’s towards people or inanimate things, or smaller creatures, respect can only be a good thing, right? I think it does make a difference. I do believe in things people can’t measure, and I think respect has a resonance. It has something that goes beyond just our visible reality.

Did you have a driving mission throughout the process of piecing together this book?

One of the most important motivations for me is to impress the five-year-old child I used to be. I wish I could go back and say to that kid, who was sticking bits of newspaper in his encyclopaedias wherever a frog appeared, and say ‘You will one day produce a guidebook for a country that has things that you discovered.’

Also, every photographer wants to see their work used. They want to see their photos have meaning, rather than sitting on a hard drive. This is the perfect vehicle for that. I’m not just going out taking stuff which a few people see and say, that’s nice. The book has got meaning, it’s got purpose.

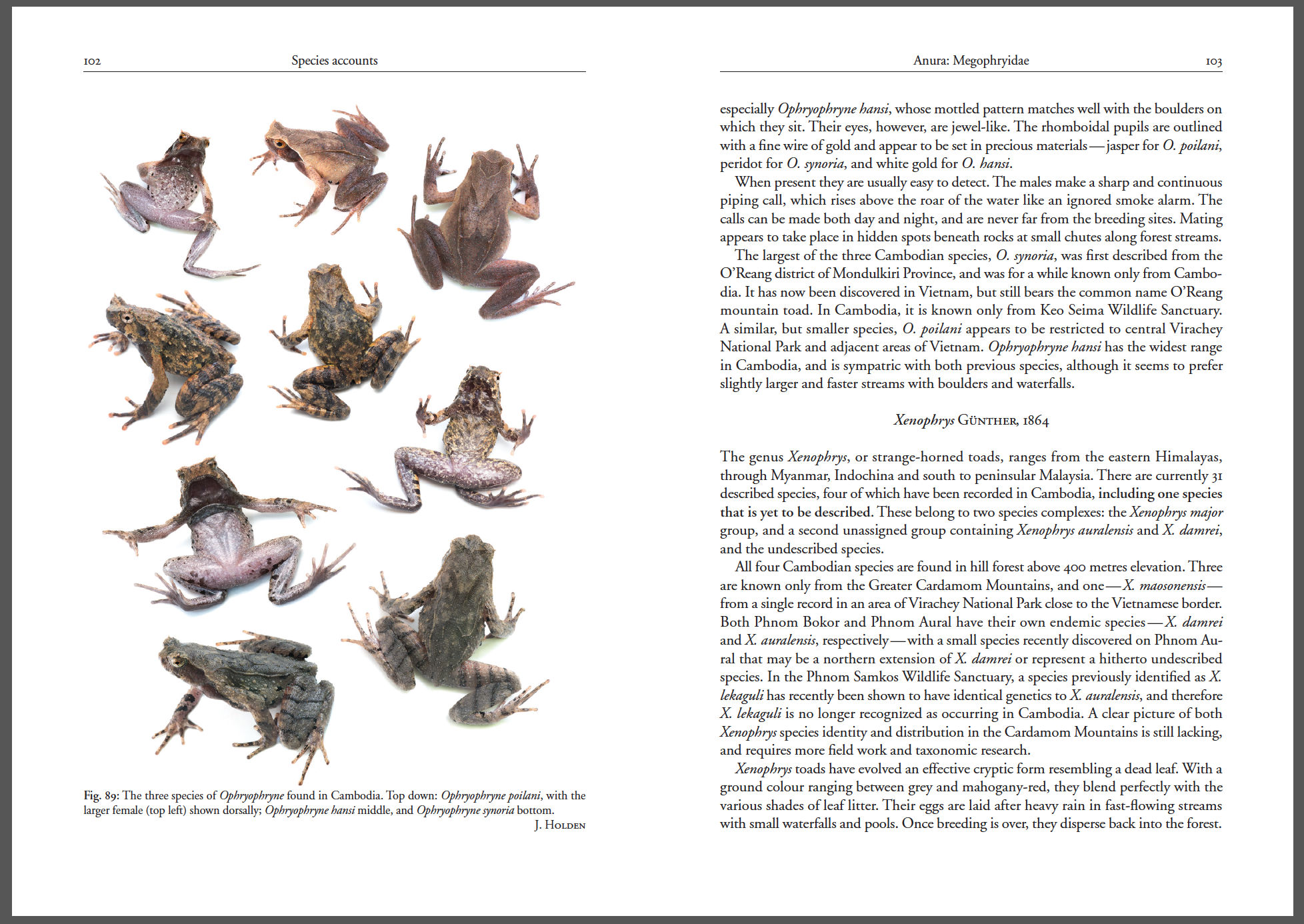

The images in the book will hopefully get people interested in frogs as more than just something you barbecue on a stick, or something that keeps you awake at night in a village, suddenly they have an identity.