Editor’s Note: This article is the second in a three-part series addressing landmines and other unexploded ordnance in Cambodia, a remnant of past conflicts continuing to impact the safety and livelihoods of people living near former war zones.

The red signs staked into the bleak landscape stood out distinctly from the yellowing crops and browned piles of soil. The only contrast more visible were the white skulls and crossbones on each sign with the warning “Danger!! Mines!!”

If all goes to plan, always an uncertainty when dealing with decades-old explosives, those signs will be toppled across Cambodia in the coming years.

In 2018, the Kingdom released a National Mine Action Strategy with the goal of declaring the country landmine free by 2025. This goal applies to known landmine fields across 946 square kilometres (365 square miles), according to the strategy.

In advance of the announcement, Cambodia adopted the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and added another target: “end the negative impact of mines/explosive remnants of war and promote victim assistance.”

“Young men and women working on the ground to clear landmines inch by inch, metre by metre, every day. They are our heroes,” said Ly Thuch, a senior government minister and vice president of the Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA).

The removal of landmines and other unexploded ordnance, also known as ‘mine action,’ is regulated through the CMAA, which works with government agencies such as the Cambodian Mine Action Centre and the National Centre for Peacekeeping Forces. The authority also partners with humanitarian demining groups, including the Mine Advisory Group, HALO Trust, Cambodian Self-Help Demining, Norwegian People’s Aid and APOPO.

There are approximately 2,600 deminers in the Kingdom, Thuch said.

Since Cambodian mine action officially began in 1992, more than 1.1 million mines have been cleared, as well as approximately 2.9 million other explosive remnants of war, according to CMAA’s February 2022 demining progress report.

The efforts have led to 155 deminer deaths and injuries, adding to the national total of nearly 65,000 casualties of explosive remnants of war, CMAA data reports. After more than a decade without an incident, the accidental detonation of a buried stack of anti-tank mines killed three deminers with Cambodian Self-Help Deming (CSHD) in January 2022.

“They put their life in risk just to save other people,” CSHD Operations Manager Sophin Saphary said.

To understand the daily risks taken by deminers working towards the 2025 goal of clearing the country of hidden explosives, Southeast Asia Globe embedded with CSHD and APOPO crews working to clear landmine fields in Siem Reap and Preah Vihear provinces, part of the Kingdom’s most heavily mined region. The resulting photographs illustrate a day as a deminer.

~ Mine Action in Action ~

Since joining CSHD as a deminer in 2020, Moun Reaksmy, left, has discovered four landmines and two other types of unexploded ordnance with her trusted metal detector. At the end of 2021, Reaksmy worked to clear a landmine field in Toul Krous, a village in her home province of Siem Reap. Before heading into the field each day, Reaksmy warmed up by testing her detector on a training plot.

Shamsa, an African giant pouched rat, prepared for the day’s work by running down the arm of Sokeoum Oun, right. Oun is an APOPO rat handler, working to clear land ‘contaminated’ by mines in Trapeang Sanke Keut, a village in Preah Vihear, a province bordering Laos and Thailand in northern Cambodia.

~ Clearing the Way ~

Before mine detection and disposal begins, vegetation and brush need to be cleared to improve visibility and thus the safety of deming crews. But the method depends on the condition of the contaminated land.

CHSD deminer Koy Seudy, left, spent about an hour carrying away armfuls of brush to clear the 50 square metres (538 square feet) he was assigned to in Tuol Kruos in early December. An excavator brush cutter, right, is used to fell trees to create a safe path for APOPO and Cambodian Mine Action Centre demining crews in Trapeang Sanke Keut village.

~ Differing Detections ~

Metal detectors often send signals indicating the discovery of any type of metal. Deminers clearing contaminated land in Tuol Kruos have come across various remnants of war fragments, top right, including shrapnel and bullet shells, as well common items including nails. Reaksmy has detected roughly 120 similar fragments since joining CSHD in 2020. Reaksmy demonstrated, top left, how she cleared away dirt after a metal detection.

The African giant pouched rats used by APOPO are trained to scratch the ground only detecting an explosive scent, explained Michael Heiman, APOPO’s Asia regional manager. Jeehwan sniffed his rat handler, Sophea Mao, bottom left, after detecting the location of an anti-personnel landmine in Trapeang Sanke Keut. Zefania, bottom right, scratched at the ground to indicate explosive residue at an APOPO training area in Siem Reap.

~ Identifying Threats ~

‘Unexploded remnants of war’ is a broad term used to describe the munitions and ordnance continuing to plague Cambodia following three decades of conflict last century.

Landmines are often referred to as a separate category of unexploded remnants of war, with two different mine types: anti-personnel, top left, and anti-tank, top right. These two Soviet-made mines, a PMN-2 and a TM-46, were detected by APOPO rats in Trapeang Sanke Keut village. More than 1.1 million anti-personnel and nearly 26,000 anti-tank mines were cleared between 1992 and February 2022, according to a CMAA demining progress report.

Unexploded remnants of war also refers to unexploded ordnance and abandoned explosive ordnance. The former refers to weapons fired during conflict that failed to detonate as designed. The latter describes weapons never fired and left behind.

A mortar, bottom left, is used at the APOPO headquarters in Siem Reap as an example of unexploded ordnance to educate the public. While rocket-propelled grenades, bottom right, recovered from a suspected Khmer Rouge weapons cache and stored at the Golden West Humanitarian Foundation facility in Kampong Chhnang, are examples of abandoned explosive ordnance. The CMAA report, which did not differentiate between types of ordnance, records the clearance of more than 2.9 million explosive remnants of war.

~ Destroying Threats ~

Explosives are often used to destroy landmines and other unexploded ordnance. While explosive harvesting exists in Cambodia, landmines are often too dangerous for deminers to move, according to CSHD Field Officer Sin Kosal.

Kosal’s team detected a Type 72b anti-personnel mine in Tuol Kruos village in December. The Chinese-made 72b is slightly easier to detect, compared to the 72a, because of an anti-tilt device requiring more metal, Kosal explained. The visible part of the detected mine, bottom left, included the side of a green, cylinder casing. The mine was reduced to charred pieces after detonation, bottom right.

“I want to be one of the citizens working with both the government and communities to rid the land of landmines and save the lives of people from Cambodia,” said Kosal, who has been involved with mine action projects for seven years.

~ Benefiting from Demining ~

A little more than 70% of land cleared and released back to owners since mine action began in Cambodia has been put to agricultural use, according to the Geneva International Centre of Humanitarian Demining. While farmers often wait years to safely cultivate their land, many face a new threat to their livelihood.

“I am very happy to have the landmines removed. This will make my family much safer. Also, I have plans to grow vegetables, like morning glory, spinach and lemongrass. I will be able to feed my family and hopefully even sell some of the vegetables,” said Pov Vanna, top left, a villager in Toul Krous who hopes CSHD will clear his half-hectare (1.2 acres) in 2022.

Senchey village in Preah Vihear is home to several farmers whose land was cleared of landmines and other unexploded ordnance in 2021. Top centre to bottom: Ream Dom, Hen Sonn, Lem Phary, Kean Log and Hol Yeou.

Preah Vihear province borders Laos and Thailand in northern Cambodia and is part of the most heavily mined region in the country. As of March, there were still more than 500 square kilometres (around 193 square miles) of contaminated land in Preah Vihear, CMAA reported.

~ Safeguarding Cambodia’s Future ~

Even if goals are met and Cambodia is declared landmine free in 2025, other unexploded remnants of war will continue to be a concern. The challenge needs to be met with more investment in explosive ordnance disposal and risk education, Thuch said.

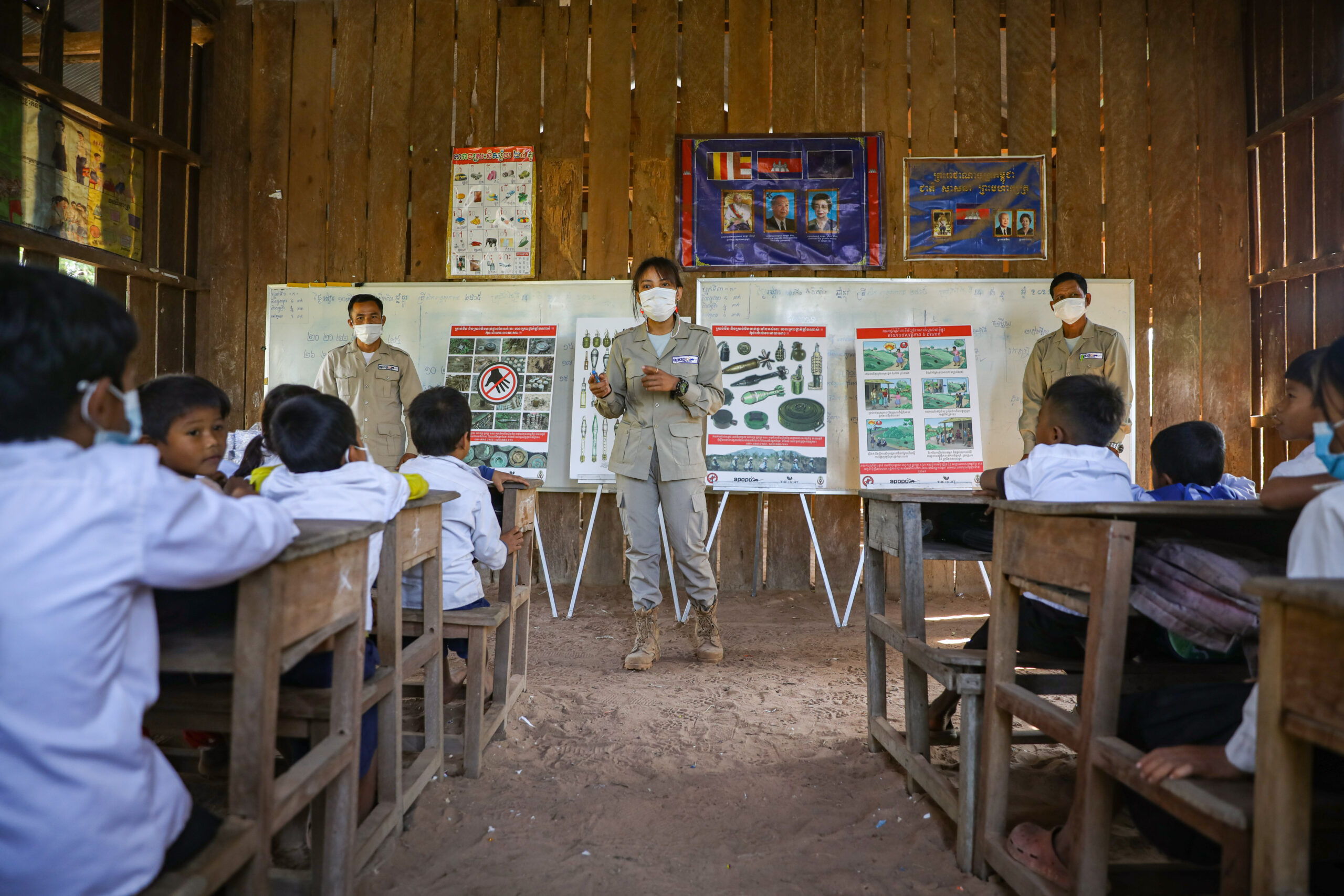

With a stack of notebooks balanced in one hand, Chey Vannoch handed out free notebooks as she passed each row of students at a school in Preah Vihear’s Prey Smach village. The booklet’s back page, left, features six comic panels depicting the stages of explosive risk education and safety behaviour.

Before going into explosive ordnance risk education with APOPO, Vannoch worked as a dog handler for landmine detection and as a deminer for the Cambodian Mine Action Centre.

“If I compare, each job I have had – deminer, dog handler and educator – each has been special,” Vannoch said. “I hope in the future, all the people will understand the risk of mines and unexploded ordnance. Hopefully in the future after that, there will be a day none of those jobs are needed anymore because everyone is safe.”

The first part of the three-part series on landmines and unexploded ordnances can be found here and the third can be explored here.