Credit officers called Kamblor Sanok every day for three weeks to demand he pay back his loans.

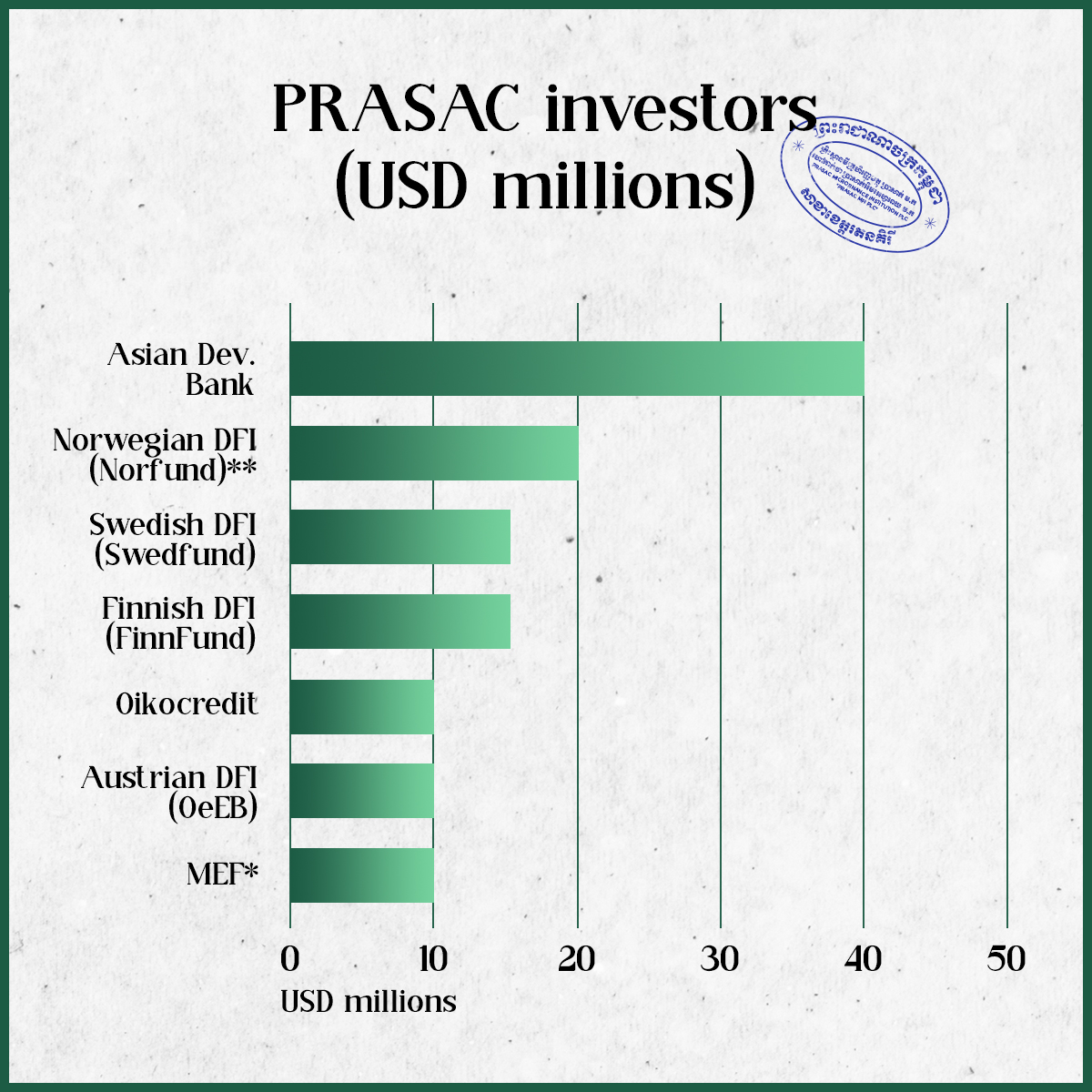

The employees of the PRASAC Microfinance Institution Plc. repeatedly warned Sanok he had lied about his ability to pay by his March deadline. As the constant phone calls and intimidation continued, Sanok could not sleep.

“There is a fire in my head, like my brain is overheated and ready to explode,” Sanok said.

Cambodia has the world’s highest average microloan debt per person at $4,280, despite a GDP per capita of $1,543 in 2020, according to the World Bank.

In Sanok’s home village of Kres, one of eight indigenous Kreung villages in Poey commune in northeastern Cambodia’s Ratanakiri province, the burden of this debt weighs heavily on the rural poor. More than 70% of Kres residents are in debt, according to research by human rights NGOs Licadho and Equitable Cambodia.

As the village chief, Sanok was well aware of the severe debt afflicting Kres residents, even as microlenders promised to help develop the community.

“[Microfinance] hasn’t helped reduce poverty, it hasn’t helped us to improve our livelihood,” Sanok said. “There’s nothing left for our families, everything is going to the microfinance payments.”

Marginalised from Cambodia’s dominant Khmer culture, indigenous villagers are especially vulnerable to the downsides of microfinance debt, which in Kres has prompted land loss and deforestation.

But indigenous people also have strong land rights that experts say the microlending industry is violating in pursuit of profit, illegally mortgaging protected communal land for individual loans that villagers struggle to repay.

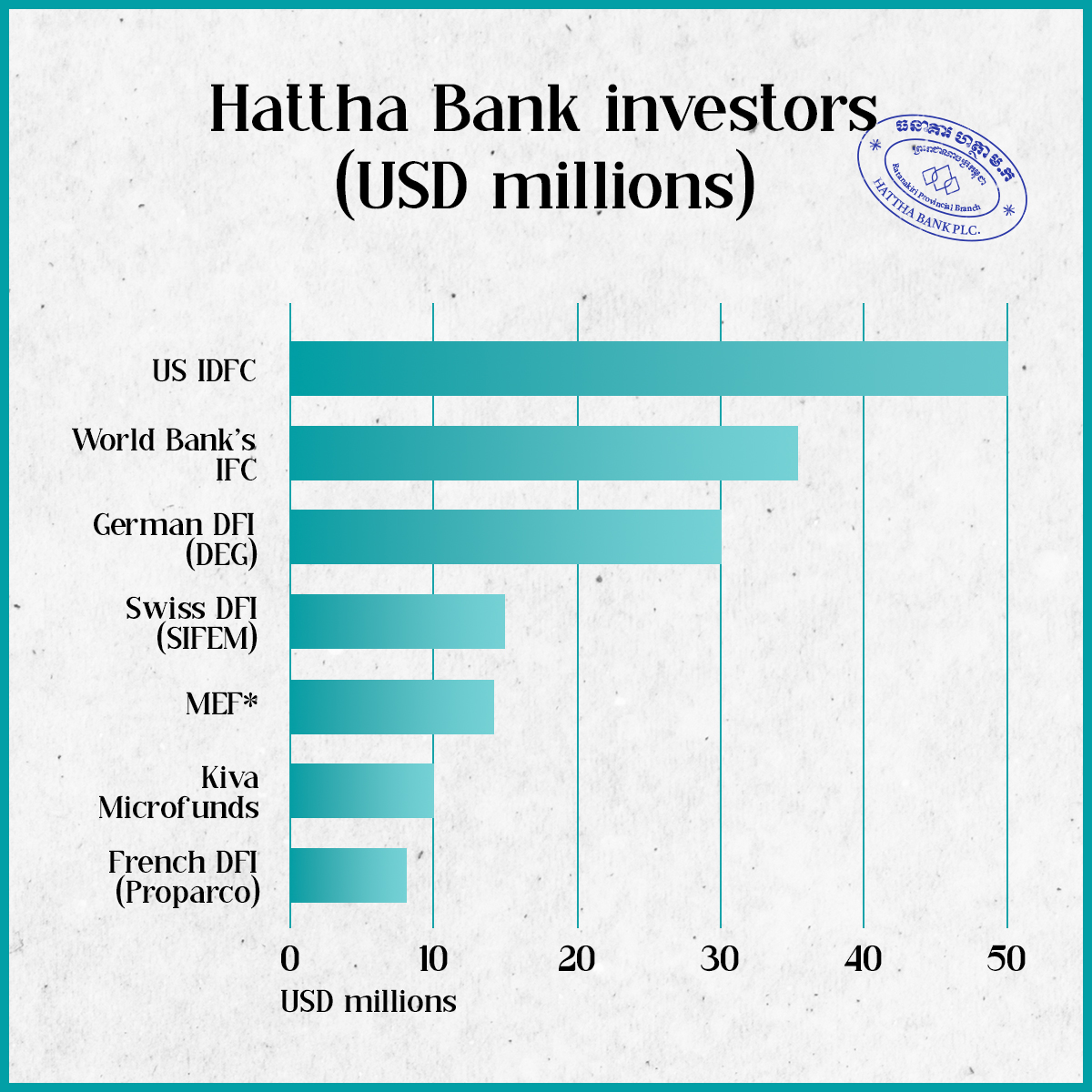

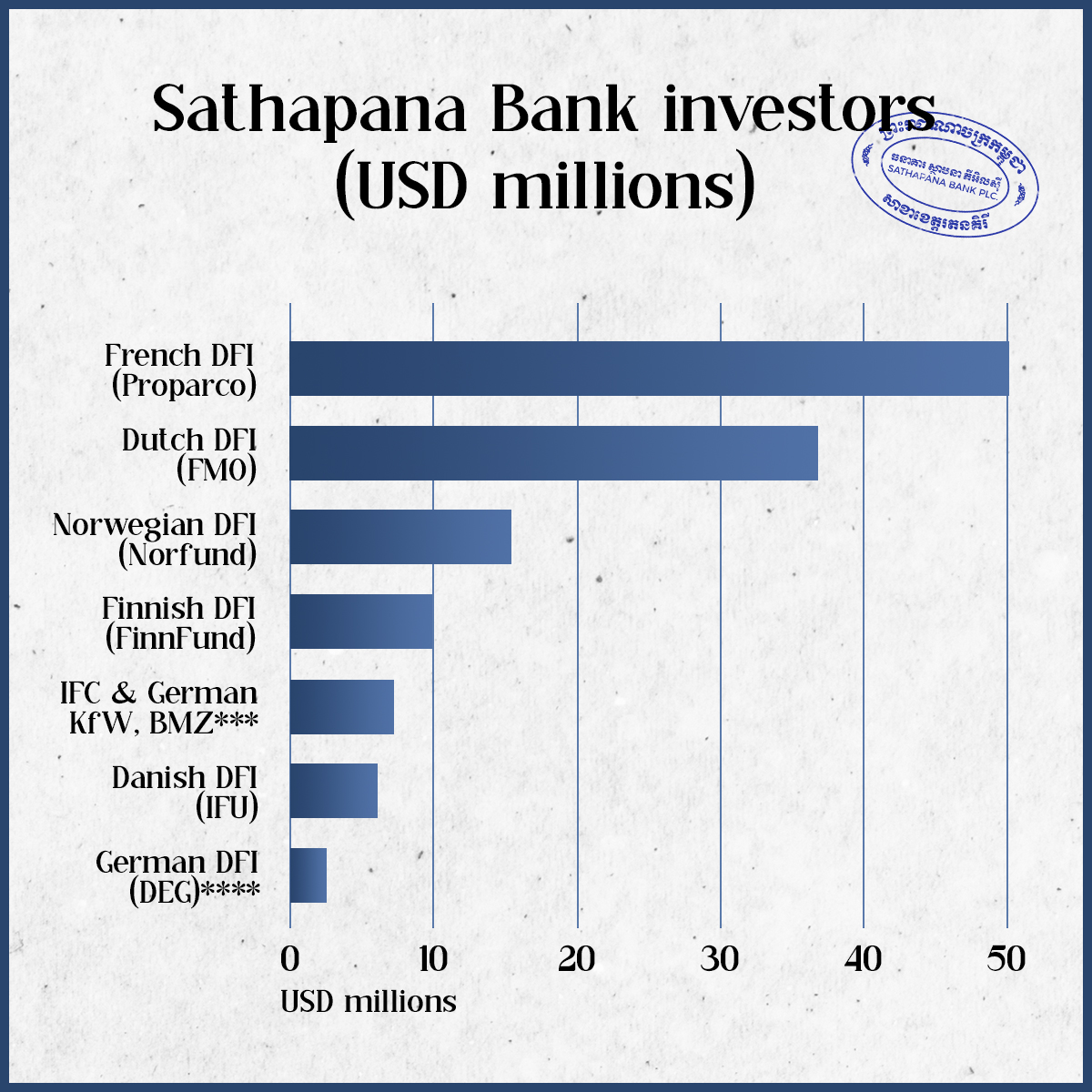

There are at least 10 microlending institutions operating in Kres. These businesses receive millions of dollars from numerous government-run European development financial institutions (EDFI), the Asian Development Bank, the U.S. government’s International Development Finance Corporation and the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC).

The institutional investors mandate strict environmental and social regulations to protect vulnerable indigenous communities. The IFC Performance Standards ban “activities that impinge on the lands owned… by Indigenous Peoples” and EDFI prohibit the destruction of “high conservation value areas.”

Compliance Advisor Ombudsman, an auditing unit within IFC, plans to review alleged violations of IFC’s performance standards by six Cambodian microlenders, according to a 3 May announcement by LICADHO, which filed a complaint with Equitable Cambodia. The lenders named in the complaint, which are responsible for 75% of Cambodia’s microloans, include ACLEDA Bank Plc., Amret Microfinance Institution, Hattha Bank, LOLC (Cambodia) Plc., PRASAC and Sathapana Bank Plc.

The below graphs show ongoing loans issued to support the microlending practices of PRASAC Microfinance Institution, Sathapana Bank and Hattha Bank from international financial institutions, development banks and government development agencies.

Methodology: The data is restricted to international nonprofits, development banks and institutions. The data is based on the total amount of the original loan(s) issued from each investor, based on public information issued by microlenders, government development banks and international financial institutions and when possible confirmed directly by investors.

*Microfinance Enhancement Facility (MEF) funders include: IFC, OPEC Fund, German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), German KfW Development Bank, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) and Development Bank of Austria (OeEB). MEF lists PRASAC’s last maturity payment as 25 April 2022.

**Distributed among 10 financial institutions via Norfund’s Norwegian Microfinance Initiative Fund III.

***BlueOrchard manages Microfinance Initiative for Asia (MIFA) funding via IFC, KfW and BMZ.

****The Globe could not confirm if the loan is still active, but a DEG spokesperson stated DEG funds multiple microlenders operating in Kres.

Microlenders have misinformed institutional investors about their lending practices, while the investors appear to accept false information about their clients’ legal compliance in Cambodia.

In the case of Kres, that includes fraudulent land titling by local officials – including the heavily indebted Sanok – who were encouraged by credit officers, according to villagers who showed the Globe loan documents and illegal land titles accepted by microlenders.

“It’s really contrary to the policies of the international banks and institutions,” Equitable Cambodia Executive Director Eang Vuthy said. “They need to make sure [microlenders] comply.”

International development banks investing in Cambodia’s microlending industry do not seriously investigate allegations of wrongdoing or harmful debt consequences, said Mathias Pfeifer, a programme officer for anti-hunger NGO FIAN.

“[European development financial institutions] have invested so much, for so long, in Cambodia’s microfinance sector that it is perhaps considered ‘too big to fail’ now,” Pfeifer said. “So they conveniently look the other way when evidence of severe problems in the sector and negative impacts for borrowers surface.”

Microlenders typically require land titles proving property ownership from individual borrowers, which are taken as collateral that can be seized by the lender following a default.

Many Cambodians lack certified land ownership via “hard” titles issued by the national government. Instead, they rely on informal “soft” titles granted by provincial authorities, which can be used as microloan collateral if the soft titles do not overlap with the legally binding hard titles. Soft titles are not recognised by the national government.

As an indigenous village, Kres received a collective land title (CLT) in June 2017 from the national government incorporating houses, farmland and forest areas into protected communal property. The CLT, a hard title intended to preserve indigenous culture and prevent land loss, cannot be divided into individual private property.

Kres also is one of five indigenous villages jointly managing conservation of the Ya Poey community forest, an important Kreung cultural site adjacent to the Kres CLT land. The national government in 2003 protected the forest from being sold, transferred or included in soft titles.

Ya Poey was intended to preserve practices such as subsistence gathering among the surrounding Kreung villages, said Chansophea Sompoy, a land rights expert with Cambodia Indigenous People’s Organisation (CIPO).

Microlenders asked Kres residents seeking loans to provide soft land titles, which required local authorities to illegally confer individual ownership over portions of Ya Poey forest or the village’s CLT.

Despite spending years managing Ya Poey while working for conservation NGO Non-Timber Forest Products, Keo Ram introduced microlending to Kres in 2012 when he began working for one of Cambodia’s biggest banks, Sathapana Bank Plc. Now a Ratanakiri-based Sathapana supervisor, Ram said the Kres villagers “are like family” whose lives the bank is committed to improving.

“We have to bring the product to them,” Ram said. “Like selling snacks… we show them what they want.”

While acknowledging the bank still issued loans in Kres requiring soft land titles, Ram denied legal wrongdoing and argued commune authorities were to blame for illegal titles accepted by Sathapana. However, he admitted to training the same authorities about the CLT and helping Kres map its communal land.

Commune authorities said in interviews that they signed off on more than 125 individual soft titles even though five of the eight villages they represent have CLT protection.

At the village level, Sanok also signed off on illegal soft titles overlapping with the village’s CLT and the Ya Poey forest since becoming chief in 2018. He claimed to have inherited the practice from his predecessor and faced pressure to allow family, friends and neighbours to access microloans.

Microlenders offer group loans, enabling several people to mutually guarantee repayments without collateral, but the funding comes in smaller amounts, leading many residents to seek larger, individual loans requiring land titles.

Sanok used his own microfinance loans to purchase a motorbike, invest in his cashew farm, fund his daughter’s education and begin constructing a larger house. He initially believed microlending would improve the village.

“We saw that the world was changing,” Sanok said. “We thought that this is our way to keep up with how everyone else was getting ahead.”

Kres village soon became deeply indebted, with 51 households collectively owing more than $243,000 in principal to microlending institutions, according to a community survey in January. The loans carried an estimated $107,000 in interest, to be paid on average within 31 months.

At least nine families in Kres, desperate to repay microloans, sold land to people outside the community, Sanok said. Dozens of villagers seeking additional farmland also cut down swaths of Ya Poey forest, according to CIPO.

Microlenders encouraged indigenous borrowers to mortgage CLT and forest land, said Kres resident Choun Bunla, who used property to secure a PRASAC loan and became mired in debt.

“[The credit officer] said if I want to get more I just have to get my land title done and I will be able to get the second loan,” said Bunla, who eventually sold his mother’s soft title farmland to a non-indigenous person despite its location within the Kres CLT.

The Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction issued a statement in March condemning the use of soft titles in protected areas, which the ministry noted has become a widespread, illegal practice among Cambodia’s indigenous communities.

Poey commune officials overseeing Kres defended the soft titles by claiming the practice occurred throughout Ratanakiri province and they did not know it was illegal.

Authorities were encouraged to break the law because granting soft land titles fueling microlending was profitable for them, claimed Mong Vichet, deputy director of the Ratanakiri-based NGO Highlander’s Association, which advocates for indigenous communities.

Vichet said microlenders shifted the risk and responsibility of breaking the law by claiming local authorities are responsible for verifying land titles: “They [microlending institutions] don’t care if CLT or not, they care if the commune council dares to issue land titles.”

Kres residents said they paid the commune as much as $100 for each hectare covered by their titles.

Microlenders operating in Kres assured investors they do not violate any policies or laws.

In turn, development banks funding microlenders denied allegations that protected lands were accepted as collateral or sold to repay debt. Microloan documents and statements from villagers and the lenders themselves attest otherwise.

Of the 10 microlenders issuing loans in Kres, only Sathapana and Hattha, formerly Hattha Kaksekar Limited, responded to requests for comment.

In an interview at Sathapana’s Phnom Penh office, Head of Credit Operations Koy Chamroeunvichea admitted there were 15 active loans secured with Kres land as collateral, while Chief Risk Officer Meng Veasna falsely claimed Kres had not received CLT status until December 2021. Government records show the village received a CLT in June 2017.

Sathapana officials also appear to have misled investors, including the Norwegian investment fund Norfund and the Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank (FMO). In written statements, Norfund and FMO representatives repeated Sathapana’s inaccurate claims that loans to Kres were legal because the village did not yet carry CLT status. FMO invested $20 million in Sathapana in April, classifying the loan’s environmental and social risk as “low.”

Sathapana officials acknowledged they could not share any evidence to support what investors claim they were told. But communications head Adam Lee said the bank must “rely on the communities to verify whether the collateral is correct or not. We have to take their word for it.”

Hattha Bank, whose investors include the IFC and the U.S. government’s IDFC, also accepted illegal land titles. Multiple written requests by Kres villagers to the commune for unlawful soft titles bore Hattha’s stamp. In some cases, Hattha issued collateral receipts indicating the land was mortgaged.

Within a CLT or protected community forest, no individual borrower can claim ownership of land for the purpose of a loan, according to Equitable Cambodia and CIPO. “None of this land can be used at all” for collateral, said Sompoy, the indigenous land rights expert.

Yet investors seemed to believe CLT land could be converted into individual property. Norfund stated Hattha used soft titles from Kres to verify “ownership of the borrower.”

Hattha Chief Distribution Officer Leang Siebh stated the bank was aware of the Kres CLT and had accepted soft land titles from villagers, but said this was only an administrative measure. “We do use the soft title for the deposit in order to identify the address, the ownership of the collateral and to know if the client has usufruct rights for the land,” he said.

Even though villagers didn’t actually own the property they used as loan collateral, many depended on land to make their living. Soft titling may have given an illusion of ownership, but often led to a very real loss.

Chavay Brang used CLT property to secure a Hattha loan to help pay for home construction, then sold Ya Poey forest land to a farmer outside the community to meet a microfinance loan used to pay back Hattha. After losing much of his stable income from the land sale, Brang began work as a day labourer.

“I am afraid of the future, what will happen to me and my family,” he said.

+

The Covid-19 economic downturn and several years of poor cashew harvests have made timely loan repayment nearly impossible for many Kres villagers. Even investments in seemingly viable business plans can quickly become overburdened by payment schedules undermining the ventures.

Kres resident Jon Lol took out two simultaneous loans to invest in farm land and cashew planting, partly using three illegal soft land titles to secure loans from Hattha.

Lol and his wife began working two weeks per month as day labourers to meet monthly interest payments of $150 and were unable to care for their cashew farm, where weeds smothered the saplings. His 15-year-old daughter and 10-year-old son left school to help the family pick other people’s cashews.

All they care about is that we make our monthly payment on time.”

Jon Lol, Kres resident

Lol said they could cultivate the farm with reduced interest payments, but credit officers remained unwilling to change their repayment schedule. Hattha countered that the bank is willing to restructure loans on a case-by-case basis.

“They don’t care about our cashew harvest, they don’t care what happens on our farm, what happens to our land, they don’t care about us,” Lol said. “All they care about is that we make our monthly payment on time.”

Sanok said the residents of Kres “have no options but to borrow from one microfinance company to pay back another microfinance company.”

Sanok rented out his farm for three years to repay part of his principal, but remained $1,000 short of his next instalment. Without loan restructuring, he planned to resign as village chief to work as a day labourer elsewhere in Cambodia or become a migrant worker in Thailand to meet years of upcoming repayments.

He said it is the only way forward in a place where debt has become all consuming: “The life is going out of us.”

Additional reporting by Borin Sopheavuthtey, Loun Hoklek and Molenna Sok.