SOPHEA* LOVES TO WALK. Small for her 16 years, she has short, boyish hair and a loud laugh that she shares with the world in a wide grin. Every day, she wanders around her rural village, not far from tourist-town Kampot in southern Cambodia, only sneaking back home for quick snacks before heading out again. In 2017, when Sophea was 14, she set out for a walk to her aunt’s house, just a few hundred metres from her own home.

She never made it.

When a neighbour finally found her, she sat slumped and naked in a field, the trampled crops around her stained red as a deep gash flashed across her throat.

Her neighbour, a 15-year-old boy, had tried to rape her, and when that failed he panicked and tried to murder her to protect his identity. Sophea has an intellectual disability, and like many others in her situation, this leaves her more vulnerable to all manner of violence. She barely survived.

Poverty, gender and disability all leave Cambodia’s women and girls living with disabilities at high risk of experiencing sexual abuse. A research paper released in 2013 by Australian Aid in association with two Cambodian NGOs – the Cambodian People’s Disability Organisation and women’s rights group Banteay Srei – found that women and girls with disabilities were far more vulnerable to violence inflicted by members of their own family.

“They were much more likely to be insulted, made to feel bad about themselves, belittled, intimidated, and subjected to physical and sexual violence than their nondisabled peers,” the report stated.

The report called for urgent action to make sure that women and girls with disabilities could access mainstream social services, and that “discriminatory attitudes which condone and perpetuate violence against women with disabilities are challenged and transformed.”

Sophea was attacked four years after the report was published.

According to Srey Vanthon, Cambodian country director for international disability charity ADD – originally Action on Disability and Development – little has changed.

“The situation of people with disabilities is not much different than from before,” he said. “Although we have many documents, policies and laws in place, the implementation of those remain challenging.”

*Name has been changed to protect the identity

The attack left Sophea with deep scars and unable to use her left arm. Her father told us that she has grown more violent since her attack. She still takes walks around the village and is well liked there. Sometimes people give her small amounts of money.

Sophea’s story

Seurn takes slow drags on a cigarette with his left hand – his only hand. He never tells us how he lost the other. The wiry 56-year-old retired commune guard, who we’ve identified only by his first name to protect his daughter’s identity, is a single parent to five daughters, all of whom live with him at home. Sophea, the youngest, observes us as we talk, occasionally letting out bursts of laughter.

There was nothing remarkable about that day, Seurn says. Not at first. He is sitting on a wooden platform outside his one-room house, his eyes reflecting the grey sky as his thoughts turn inward.

“It was around 2:00pm and I was taking a nap in the hammock,” he says. “The neighbours came to us and shouted that my daughter was slashed with a knife and nearly dead. I was shocked and could not walk to see her by myself.”

Sophea was taken to hospital, where she spent 17 days. The cuts to the tendons in her neck were so deep that she still cannot use her left arm.

“On the day of the incident I gave the suspect’s grandmother food,” recalls Seurn. “I cannot believe he could do that to us.”

Seurn is no stranger to difficult hospital visits. When Sophea was three months old she was struck down with a bad fever. The family took her to the hospital, but no diagnosis was ever made. From then on, her mental capacities never fully developed. She has never spoken a word, but she does understand, and helps with the housework when asked. Later, doctors would simply tell the family that there was no cure for what had happened to her.

After her mother passed away when she was six years old, the responsibility of caring for her fell on her father. Every day, he had to wash her, clothe her and feed her. Like most people living with disability in Cambodia, Sophea has no formal education. A non-governmental organisation (NGO) – Seurn cannot recall which one – approached the family, and at one stage Sophea attended language classes in Kampot, but she couldn’t sit still and they pulled her out of the class. The next time an NGO approached the family, Seurn told them that it was pointless to try to educate her. His daughter, he said, was too restless.

Since the attack, life is harder.

“She becomes more aggressive than before when we scold her – she will get very angry and shout,” Seurn says of his daughter.

“Sometimes, she just suddenly starts to cry and gets mad with everyone.”

Seurn points to the spot where Sophea was attacked, just a couple of hundred metres from their home

Out of reach

Ngin Saorath sits behind a large desk strewn with papers in his otherwise orderly office in Cambodia’s capital of Phnom Penh. He speaks with the careful delivery of a man who has repeated himself too often, and yet his words have not lost any of their conviction.

Saorath is the executive director of local NGO the Cambodian People’s Disability Organisation (CDPO), and a key player in pushing for rights for people with disabilities in the country.

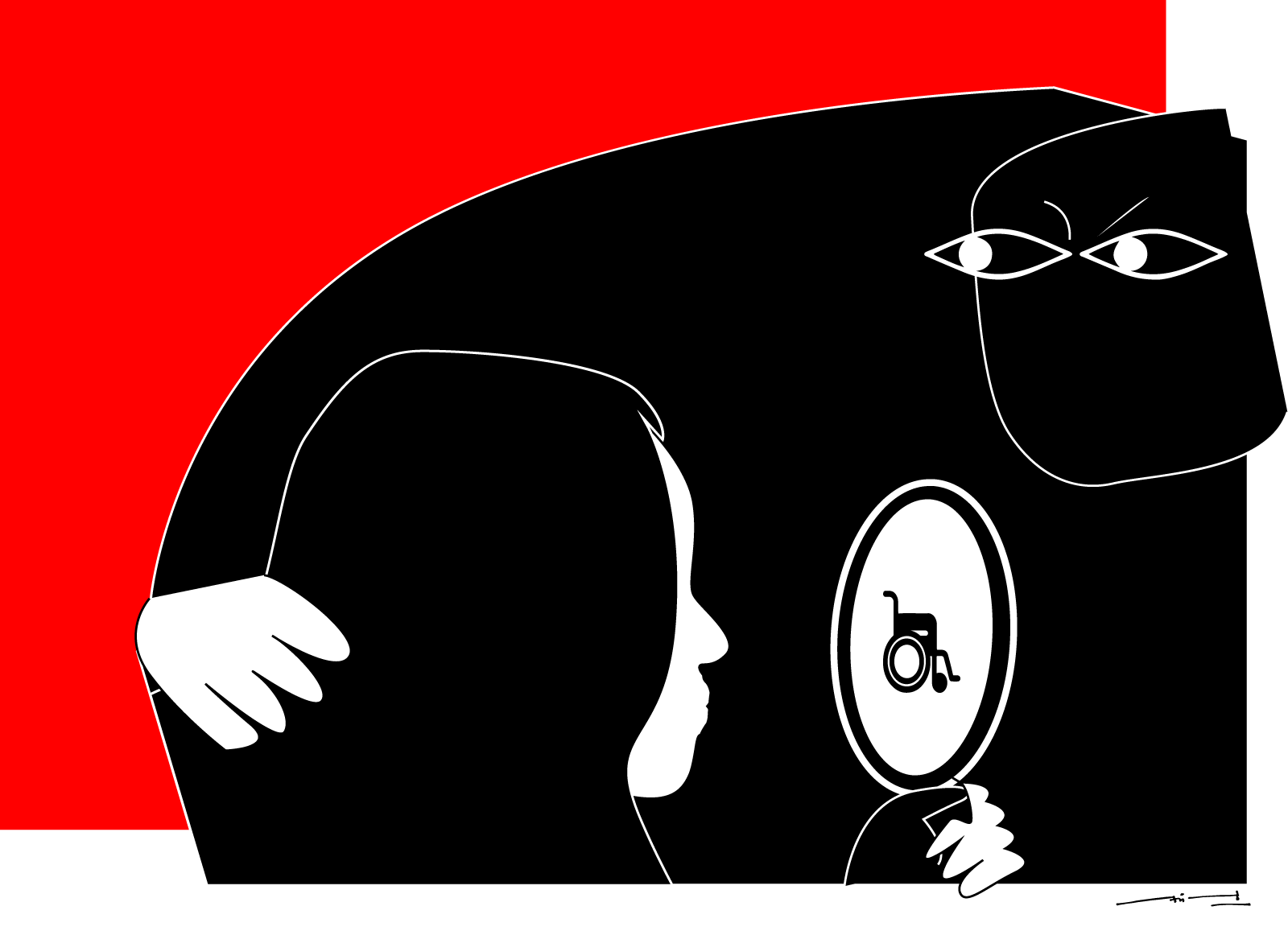

“Women and girls with disabilities live under the mirror of the world; they can see it but they cannot reach out to our world,” he said.

With no reliable data to go on, it’s impossible to know how many people in the Kingdom are living with disabilities. Estimates from the World Bank and the World Health Organisation put the global number somewhere around 15% of the world’s population.

In Cambodia, that would put the number of people living with disabilities at 2 million – 320,000 of whom experience significant difficulties with every-day living. The proliferation of landmines across the country, a legacy of decades of civil war, could well have pushed that number higher than the global average.

Saorath says that many people with disabilities remain shut out from Cambodian society.

“There is a stigma around them. It creates a barrier for women and girls with disabilities.”

This barrier extends to higher levels of authority too, where women with disabilities who are the victims of discrimination or violence are often denied access to justice.

A women’s rights activist in Cambodia, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of government reprisals against the organisation that she works for, said that there is a lack of a support system for victims of sexual violence, and often a failure by authorities to collect evidence or act on complaints.

Women and girls with disabilities live under the mirror of the world; they can see it but they cannot reach out to our world

Ngin Saorath, Cambodian Disabled People’s Organisation

“The judicial system in Cambodia is still corrupted by the rich and [by] high ranking officers, and [is] also very biased [against] women – especially if they were raped or harassed,” she said.

Vanthon from ADD International summed this up in a story: there was one particular case in Kampong Thom province that has stayed with him, he told Southeast Asia Globe over the phone. A girl with disabilities was raped. When her case was brought up at a local meeting, a member of the commune council broke the silence. The man had given the girl a gift, he said. No one else would have wanted to be with her.

The problem is worse for people such as Sophea who have non-physical disabilities such as intellectual, psychosocial or sensory impairments. An abstract on disability inclusivity written by Saorath’s CDPO notes that all 11 rehabilitation service centres in the country are focused only on physical disabilities – and these are still “insufficient to meet demand”.

Chea Bopha is a wheelchair user and the programme coordinator at the Phnom Penh Centre for Independent Living (PPCIL), an NGO that supports and promotes the rights of people with disabilities. She said that she has faced ongoing discrimination for her disability – and the resentment that came from that rejection.

“I felt so much anger – I was shy and afraid to meet people. I locked myself in my home and kept silent,” she said. Bopha said that her own situation has greatly improved since she discovered PPCIL, but that there are still many challenges facing women with disabilities.

“People have little understanding of disabilities – they look down on [people who have] them and compare them to a person without disabilities.” She said it is difficult to find a job or a partner.

‘It is too political’

The government response to supporting women and persons with disabilities has not been negligible.

In 2009, the Law on the Protection and the Promotion of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was passed. This in turn led to the establishment of the Disability Action Council (DAC), a body that falls under the Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation (MoSVY) and is tasked with working with ministries and institutions to support people with disabilities in Cambodia.

These laws, passed in many of Cambodia’s grand ministries in the urban capital, feel a long way from Sophea’s village in rural Kampot province. For her father, the priority is putting enough food on the table to feed his family. Like many caregivers of persons with disabilities in Cambodia, he is unaware that any help is available.

It is a challenge that the DAC secretary general, Em Chan Makara, is mindful of.

“Awareness raising and capacity building on disability needs to be scaled up,” he said.

There have been some early steps towards action. In December 2018, a spokesman for the Ministry of Justice announced that the government was “in the process of preparing a common national policy” to make it easier for people in vulnerable situations – such as women, children and persons with disabilities – to gain access to legal justice.

Makara also pointed to a joint project involving the United Nations Development Programme and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. It is intended to bring authorities up to speed on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – which Cambodia adopted in 2012 – and includes training for judges, prosecutors, court clerks, lawyers, prison officials and ministry officials.

But many in the disability sector still feel that this is not enough. One source who did not wish to be named, fearing government backlash against their organisation, said that “there are unclear roles between the MoSVY, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and the DAC. It is too political, and there is not enough direct action.”

And Makara admitted that within the government, there is a lot of passing the buck.

“The situation of persons with disabilities can [not] be improved unless all ministries and civil societies fully participate in taking actions to eliminate barriers that persons with disabilities [face],” he said.

For Saorath of CDPO, he believes there needs to be unity.

“I strongly believe that the government, as well as the donors and the organisations, need to work together to have solidarity… to learn more about best strategy from developed countries as well as countries in a similar situation [to Cambodia].”

It’s a piece of advice that many in the disability sector are taking to heart.

The heart of the matter

On a slightly overcast April day in a small park close to Phnom Penh’s riverfront, a group of women sweat their way through a series of dance moves. They could easily be mistaken for any one of the many exercise groups that gather in the capital each morning, but this is no ordinary meeting.

These women, all of whom are living with disabilities, are making a music video for a song titled Rise Up, a collaboration between inclusive arts organisation Epic Arts and the Cambodian branch of the Austria-based international disability development organisation Light for the World.

Bopha of PPCIL was one of the women involved in the video, which she hopes can help raise awareness of women with disabilities.

“The women can present themselves to society and can show their ability to social media and become an active person,” she said. “Everyone enjoyed it. The women made new friends and they can learn from each other.”

The music video is part of a programme that Light for the World has been running in the country for nearly three years aimed at empowering women through providing entrepreneurial training and support.

Disability inclusion advisor David Curtis said that it was essential to level the playing field for people with disabilities.

“What I say about inclusion… is with all organisations and all systems, unless you make an effort to include, then you’re always going to exclude by default,” he said.

There are now 52 women involved in the leadership programme, and Curtis has plans to take it further. He hopes to create an inclusion academy that can provide women with disabilities with skills in areas such as basic counselling, sexual reproductive health, seeking justice, first aid and business development.

The idea is that the women will form their own networks and be able to lobby for disability rights by themselves.

ADD International is one organisation embracing this grassroots approach, having recently received funding from the UN to specifically tackle the issue of sexual violence against women and girls with disabilities in Cambodia. It’s a three-year project that will be based on an approach known as Sasa, a technique that was developed by a Ugandan NGO to help fight violence against women.

Sasa, which means “now” in Swahili, is grounded in community mobilisation. Instead of organisations leading the push for change, this approach would give individuals in communities the support they need to take the lead in spreading information and knowledge about violence against women and its harmful impact.

The first year of ADD’s new project is dedicated to mapping the most marginalised women with disabilities in five target provinces around the country before launching more hands-on strategies over the following two years based on their findings.

It is only six months in, but Vanthon of ADD Cambodia is hopeful.

“This project is really ambitious in terms of engaging and adopting a sustainable model on the ground. The aim is to change the mindset of the people,” he said.

At the core of Sasa is the idea that focusing on the rights of, and being more accountable to, women and girls with disabilities is the most effective way of tackling gender and disability inequality as the root cause of the violence they experience.

But prevention is only one side of the story. While authorities and organisations are still struggling to put an end to the sexual abuse of women and girls with disabilities, those who have already been victim to it are left with permanent scars.

Seurn has little hope for his youngest daughters’ prospects.

“I don’t know what her future is going to be like,” he said. “I don’t know, without me, who will take care of her.”

CDPO’s Saorath admitted that there was still a long way to go for women living with disabilities.

“We cannot change the world overnight,” he said.

“We need time, we need human resources, we need young people to grow their mindsets so one day they will say ‘hey, we are all human’.”