The name Thorstein Veblen might not be up there with the likes of Coco Chanel and Louis Vuitton, and he certainly didn’t have their eye for design, but this late 19th-century economist made some telling contributions to the world of luxury. The Norwegian-American not only coined the term ‘conspicuous consumption’, he also noticed that certain goods actually became more popular as they got more expensive – a direct contradiction to the law of demand. These products would be forever known as Veblen goods.

In the century or so since Veblen’s time, the world’s obsession with luxury goods has exploded. In the past 20 years alone, the number of luxury consumers has trebled to about 330 million people, who spent an estimated $300 billion in 2013 according to Bain & Company, a global management consultancy. Interestingly, that money was not solely concentrated in traditional luxury strongholds such as Europe and North America. Most analysts agree that emerging markets are becoming the new darlings of the luxury industry.

Sales in Asia reached $90 billion in 2014, about the same as North America, according to London-based market intelligence firm Euromonitor International. Meanwhile, a study released in 2013 by Bain & Company stated that Indonesia and other Southeast Asian nations, including Malaysia, Vietnam and Thailand, are the “new engines of luxury growth within Asia”.

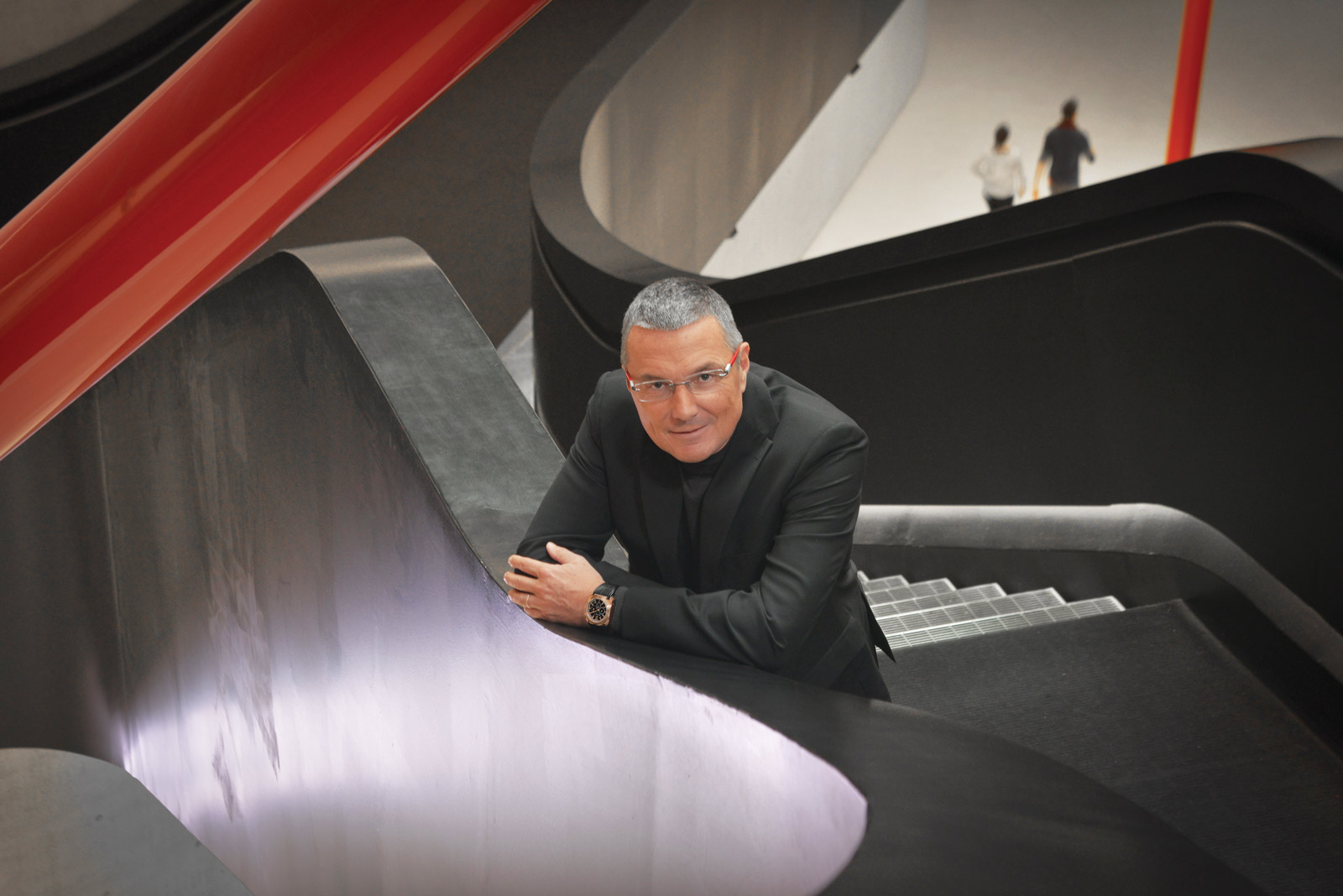

“More and more domestic people in Southeast Asia are becoming capable of entering the luxury market,” said Jean-Christophe Babin, CEO of luxury giant Bulgari. “Indonesia is a hugely populated country, then Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia – all together we’re talking about hundreds of millions of people going through economic development… This is one reason why Bulgari has added six new boutiques [in the region] in just eight months.”

Large numbers of incoming Chinese tourists is another key driver of luxury demand in the region. Partly due to inflated prices at home, Chinese consumers are renowned for doing much of their shopping outside of the country, with the Economist reporting that some spend 73% of their holiday budget on shopping. Southeast Asia welcomed more than 10 million Chinese tourists last year, according to figures from the Centre for Aviation, a research company based in Hong Kong. “The large numbers of Chinese arriving on holiday is certainly adding to the luxury market,” said Babin.

Southeast Asia is following in China’s footsteps in other ways too, with the region’s growing middle class experiencing income growth that is changing their spending priorities. In many urban centres, lifestyles are being completely redefined. Better employment opportunities have even had a direct impact on luxury sales in the Philippines, for example.

“Improved employment rates encouraged consumers to look their best at work. As such, the majority of consumers who bought luxury goods in 2014 did so to accentuate their status, with priority placed on conspicuity of brands to ensure high brand recognition among their peers and the public,” stated Euromonitor’s report, Luxury Goods in the Philippines.

Even as much of the world moves away from logos and toward ‘codes’ – understated ways of conveying brand identity, such as the red soles of Christian Louboutin shoes – a large group of Southeast Asian consumers still places value on goods that noticeably reflect their status. Broadly speaking, there are two types of Southeast Asian consumer in terms of taste.

“I would clearly differentiate between sophisticated luxury customers and customers in the emerging stage of exploring luxury. And you can find these types of customer in many different countries in Southeast Asia,” said Chris Neff, Asia managing director of Swiss luxury watchmaker Chopard. “The established luxury customer has a very good understanding of the quality of the product. So this segment is clearly very well informed and needs a different approach to be nurtured and excited further in terms of luxury consumption.

“Then you have the emerging group of luxury customers, the growing middle class that have attained an income level that allows them to buy quality, branded products. There, you need to invest a lot of time to educate them on what luxury is all about, because this group buys for two reasons: because customers trust the brand in terms of quality, and the bigger the brand or more famous the logo, the higher the trust; second, it shows society that this specific person can now afford luxury products, which is very, very important in most Southeast Asian markets.”

A key characteristic of the Southeast Asian luxury consumer is their overwhelming preference for face-to-face retail experiences. The personalised service offered by knowledgeable staff, the desire to see and feel a product before spending a relatively large amount of money, lingering doubts over counterfeit goods and even the simple desire to shop in a mall to escape the heat are all factors that push the region’s consumers toward boutiques.

Babin, however, is adamant that Southeast Asian consumers should not be afforded atypical status. “They are not so different from what we observe in the rest of the world. Global brands are communicating very evenly across all four continents. People follow the same websites and the same social networks. I think we have to forget the times when we’d say: ‘The Chinese taste is so different from the American taste, which is totally different from Europe.’ No. There is probably the same taste difference between Shanghai and Chengdu as there is between Shanghai and New York.”

Yet research by Agility Research & Strategy, presented at Retail Congress Asia-Pacific 2015, seems to paint the opposite picture. They identified four distinct categories of affluent Asian shoppers, from the “exclusivity seeker” to the “indulgent traveller”. The firm also branded a set of ambitious and affluent young consumers as “Generation AAA”, a key group for brands to focus on. This group spends equally across jewellery, tech, travel and fashion and has embraced digital technologies.

“Luxury brands can reach out to AAA consumers by first understanding their demographics and psychographics. Who are they? Where do they spend? What are their hobbies?” Amrita Banta, managing director of Agility Research & Strategy, told luxury marketing website luxurydaily.com. “One of the most common misconceptions about affluent Asian consumers is that they are all the same.”

One way that global brands have reached out to regional consumers is through events, where brands seek that elusive connection with customers and aim to woo them with their potent synthesis of timelessness and modernity. Gregoire Blanche, regional managing director for Southeast Asia and Australia at Cartier, details the company’s recent Etourdissant Cartier event in Singapore, where, in a sign of Southeast Asia’s growing status, more than 600 pieces made their world debut.

At Bulgari, Babin cites the company’s luxury hotels, currently open in three locations, including Bali, which he describes as “ultimate experiential temples of the brand”.

In luxury brands’ battle for hearts, minds and wallets, nothing can be left to chance. Yet a delicate balance is required. Some consumers aspire to the luxury lifestyle with every inch of their being; others find it shallow, particularly in regions where millions live in poverty. The challenge for brands is to continue satisfying the former while deftly wooing the latter.

“In this journey of educating emerging luxury customers you always lose some clients along the way. That’s natural,” said Neff. “But there is a great opportunity by coming [into markets] early and being the first to offer luxury products… That’s one of the ways. But by doing that you have to be very authentic in the way you promote your brand. It’s not an approach where you can implement the same luxury strategy in any country. It requires patience; you have to invest a lot of time in understanding the local market and the mindset of the customers. That is how you build loyalty.”

Offering an exquisite product is also rather important. Most Southeast Asian consumers’ first interaction with a brand will be through an entry-level product such as perfume, accessories or lower-priced jewellery. “Luxury brands cannot afford to offer an entry-level product which is not of excellent quality,” Neff pointed out. The most successful companies not only retain the lustre of their $3,000 handbags, they also bathe their $30 mascaras in its iridescence.

For most luxury brands, the first step is increasingly taken digitally. Live streams of catwalk shows, web-only videos and endless interaction on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest and Instagram are now the norm. Famed British department store Harrods even created a game named Stiletto Wars, not so loosely based on Candy Crush, to promote a shoe sale.

“The digital component is sometimes the first touch point we have with our clients,” said Blanche. “It is a key part of the storytelling behind our creations and also offers readily accessible details about them. In fact, Cartier was one of the first players in the digital world, with our L’Odyssée de Cartier digital film in 2012. That is an example of how we used technology to really bring our creations to life with immersive storytelling.”

The film has rightly gone down in luxury marketing history. Comments such as: “It’s the most enchanting advertisement I have ever come across,” are indicative of the response it has received on YouTube, where it has been viewed 18.1 million times.

However, experiencing and buying are two very different things. Engaging with customers online is widely seen as the first step – albeit one that requires a great deal of effort – in a sequence that ends with someone actually entering a store and buying a luxury product.

“Chopard and many other luxury brands have a strong online presence and are working on strategies to reach new clients and help them get attached to the brand before they’ve even purchased it,” said Neff. “How do we turn that attachment into sales in Southeast Asia? Well, the emotional attachment to the brand is the first step. You create that with marketing, making the brand relevant to certain consumer groups by linking it to regional celebrities. Then you provide additional information about the credibility, authenticity and history of the brand to give customers confidence that they are buying a product that has a soul.”

Babin, however, sounds a note of caution: “Digital advertising is a new way to invest in media and has far more possibilities than ever before. But it also has far more question marks. In traditional media we know exact information such as the reach, the frequency and the efficiency… I’d estimate it took about a century to master traditional advertising, so with digital we’re going to have to go much quicker.”

One area where the region is certainly swimming against the tide is e-commerce, a key space for marrying up online interaction with instant gratification through purchases. Consumers in more mature luxury markets are turning to the likes of Net-A-Porter, a high-end fashion website with a customer base of six million, according to the Economist. But in Southeast Asia, e-commerce for luxury goods is simply not taking off, despite the fact that, according to Neff, “Southeast Asian customers are among the most social media savvy in the world”.

A number of factors are in play here, including Southeast Asians’ aforementioned fondness for malls, a relative lack of credit cards and secure payment systems, the counterfeit conundrum and, according to Babin, a lack of websites in local languages, something he says is “fundamental” for e-commerce. Perhaps the biggest limiting factor, though, are the logistical challenges posed by poor infrastructure and a lack of trust in delivery systems.

“In the US there are three or four delivery companies, the likes of FedEx or UPS, that are very reputable, so for people there it’s normal to buy a $2,000 Bulgari ring online and have it delivered without ever worrying whether it’s counterfeit or that it might never arrive,” said Babin. “In Southeast Asia, sophisticated private delivery companies aren’t as widespread or accessible.”

It seems that, even as some brands tailor their approaches to individual markets and others adopt sophisticated digital strategies, luxury companies know that for the foreseeable future there is no substitute for shopping in a boutique, particularly in Southeast Asia.

“It is clearly the expectation that it will be a long time before e-commerce is up and running in Southeast Asia,” said Neff. “The craftsmanship, the materials being used, the sophistication of design being implemented – which are the fundamental decision-makers when purchasing – can only be seen by the naked eye, by feeling the product. At the end of the day, you buy with emotions. We are selling emotions. We are selling dreams.”