If you were to describe yourself as a food ingredient, what would you be?

Dee May Tan, founder and editor of independent food culture magazine Plates, described herself as the Southeast Asian mangosteen, which she said is the “queen of fruits.” The number of petals on the surface of the fruit, also known as stigma lobes, corresponds with the delicate, juicy fruit segments inside.

“What you see is what you get, this is it,” Tan said. “There’s no pretence.”

With a mission to redefine food narratives, Tan started Plates to seek out underreported stories about the food supply chain and the people involved. She writes about food culture from the lens of human rights, social justice, heritage and the environment to shed light on significant issues and provoke crucial discussions, one ingredient at a time.

The inspiration to start Plates was seeded one night during a conversation over a meal with a friend.

“It was really just a concept to focus on one ingredient and broaden the conversation around that ingredient. You let the ingredients speak for itself, through people who touch, plant, trade or cook with it,” she explained.

In food writing, celebrity chefs and food writers from the Global North dominate. Narratives of marginalised communities at the early stages of the food supply chain, such as rural farmers or indigenous tribes producing food, are limited in mainstream media.

Tired of the status quo favouring elite-centric magazine features, Tan aimed to give a greater voice to people on the ground who grow, cultivate and harvest.

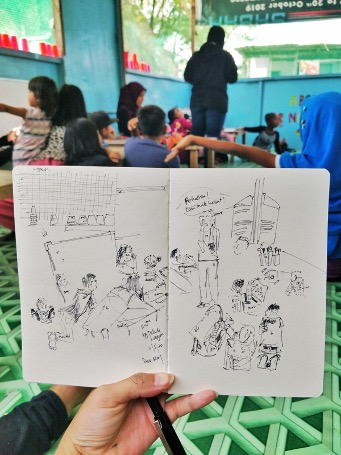

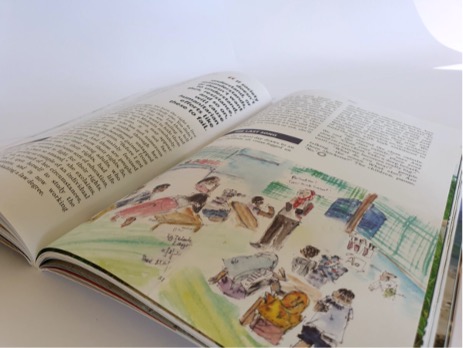

Photo: courtesy of Dee May Tan

“Why don’t we portray the makers as an equal? Usually when we talk about people like the farmers, it’s always ‘Oh, kesiannya!’ (‘That’s so pitiful’ in Malay),” she said. “The farmers are probably very proud of what they do and they just live a different lifestyle, with fresher air and food that they harvest on their own. So who are we to judge?”

A 2016 Chevening scholar who holds a master’s degree in multimedia journalism, Tan always wanted to be a force for change, but she does not enjoy political journalism: “I can start conversations about heavier issues and replace it into something more digestible, more palatable.”

The first issue of Plates, ‘Rice,’ was published in March 2019. From designing to marketing and distribution, she runs the show on her own. Spontaneous connections and daily conversations with local people are her best story leads.

“I will spend anywhere from two weeks to six months in a location to just let the stories come out. When you are alone, I learned to be a lot more resourceful and just talk to people,” Tan said, explaining that she sketches her subjects before taking photographs, which also sparks conversations.

“Sketching allows me to see things that I wouldn’t have captured in a photograph, it allows me to just slow down and absorb the environment,” she said.

In 2019, Tan was in Tubau, Sarawak, part of the Malaysian state of Borneo, gathering stories from longhouse elders about Laké Dian, a mythological leader figure of the Kayan ethnic group. A friend in Berastagi, a town in North Sumatra, Indonesia, told her about a durian that sells out the moment it reaches the town, despite the prospective buyers not having inspected the fruit beforehand.

When she arrived, the locals told her she had met a durian dead end. Berastagi is in the highlands and the climate is too cold, while durians are all mostly from Medan.

“I hung out with the locals, got invited to a wedding and tried to live like them. I went to the pasar (local wet market) with them and talked,” Tan said.

During the trip, she learned about Karo coffee, a crop local farmers turned to harvest after a volcanic eruption destroyed their orange plantations. It is now a story in her fourth and latest issue, “Seeds.”

Cultural appropriation and racial disparity are on display on the international food writing scene, Tan noted.

“There is also a trend of writers and celebrity chefs [from the Global North] publishing stories, cookbooks and recipes from Southeast Asia. They take all these recipes from your everyday aunties and uncles and they become ‘experts’ in a certain cuisine,” Tan said.

Cultural appropriation and racial disparity are on display on the international food writing scene

Elizabeth Haigh, a Michelin-star celebrity chef and owner of a Singapore kopitiam-style restaurant in London, faced plagiarism allegations in her October cookbook, “Makan.” Haigh’s debut allegedly lifted recipes and introductions from the 2012 cookbook memoir, “Growing Up in a Nonya Kitchen,” by Sharon Wee, a lesser-known Singaporean author of colour.

Asian food ingredients also can be the subject of cultural microaggressions and orientalist depictions in mainstream media. Food writers and journalists have berated the jackfruit as an “unharvested pest-plant” and durians as the “stink of death,” but articles have also have applauded new discoveries with Asian ingredients such as turmeric lattes or jackfruit meat.

Tan believes breaking free from that conditioning will take some time: “This only happened a couple of years ago when I started realizing, how can they call these foods that have huge cultural significance to people from Southeast Asia all sorts of names on an international media platform?”

Plates is Tan’s attempt to take back ownership of indigenous food narratives.

“There’s the question of appropriation, but also how Southeast Asians are not talking about our own ingredients,” Tan said. “Why are we waiting for journalists and writers from the West with a Eurocentric point of view to do so? It was about finding a way to get people to be proud of what we already have.”

During a pitch to an independent bookstore in London, Plates was dubbed “too niche” and “a little bit too Asian,” Tan recalled. Yet she said the bookstore offered magazines entirely focused on American and Western European narratives.

Tan hopes alternative media gain more opportunities to appear in literary festivals, food events and other cultural outlets.

“I hope that the curators and the programmers begin to look outside of their existing network and listen to the people in the crowd, to search for underrepresented narratives and stories, to use their privilege and create space for others,” she said.

Plates is sold by 32 retailers in six countries, but there are only seven across Asia, all in Malaysia and Singapore. Throughout four years of producing Plates, Tan still encounters difficulty widening her magazine’s distribution and convincing people they are missing out on alternative food narratives.

“Going back to the readers, I hope that they realise that they are in a position of privilege and as a consumer they have to ask, why is this person not at the table? Who else can I bring to my table? Be part of the change that they wish to see more of in the world,” she said.

Dee May Tan was a resident artist at Rimbun Dahan, a private arts residency outside Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, from October 2020 to April 2021. She recently launched her fourth and latest issue of Plates Magazine, ‘Seeds’, on the 17th October. The complete collection of Plates Magazines are available for purchase here: https://platesmagazine.com/shop/ .