The body of a tiger lies lifeless in the freezer. It is stretched out, mouth agape, with a plastic bag of unidentified animal bones resting on its flank.

This was the condition in which the big cat was found this month on 16 September in Vietnam’s Ha Tinh Province. The carcass was being kept illegally to be processed into tiger bone glue.

In Vietnam, the once-ubiquitous Indochinese tiger is today functionally extinct in the wild, with 228 known to have been killed at the hands of wildlife trafficking networks between 2003 and 2019. The species is not alone in its plight.

Vietnam is one of the most biodiverse nations in the world, but decades of habitat loss, a lack of law enforcement and the demand for traditional medicine and bush meat have left many species near extinction. Others have disappeared from the wild completely.

“Vietnam is one of the biggest consumers of illegal wildlife products,” said Hong Hoang, the founder and executive director of the Ho Chi Minh City-based environmental conservation non-profit CHANGE.

“Awareness has been the biggest challenge for NGOs like us,” she told the Globe. “The general public would not consider endangered animals playing any role or contributing any value to their lives, so the concept of saving these animals does not really exist.”

It’s that crucial lack of public awareness of Vietnam’s at-risk species that young illustrator Đinh Kiều Dương is working to address through her artwork. With younger generations increasingly mindful of the bleak status of the country’s wildlife, like-minded artists have sprung up independently to do the same.

Whether sharing information on social media, collaborating on children’s books or working with animal conservation groups, the artists strive to bring attention to the plight of animals in the country.

“We’ve been viewing wildlife as a resource and as a commodity for as long as our history,” Dương told the Globe. “Families now still have bear bile extract and python fat in their fridges as [part of their] first aid kit, believe it or not. My family does, a lot of my friends do too and we are the people who work in wildlife conservation.”

Dương worked as a graphic designer for environmental organisations Education for Nature and Save Vietnam’s Wildlife before focusing on her art and storytelling full time, a medium she believes holds great power to reach people.

“Not many Vietnamese actually know about the local wildlife issues,” she said. “NGOs alone cannot solve all these problems without the understanding and willingness of the whole community.”

A wild tiger has not been seen in Vietnam for more than 20 years. However, attention was brought to illegal breeding of the species in August when police confiscated 17 adult tigers being raised in basements in Ha Tinh’s neighbouring province, Nghe An. The central province has a history of tiger farming that is often ignored despite its illegality.

“This guy is so popular lately,” Dương said in a Facebook post, referring to an illustration of a tiger after the animal’s seizure by authorities. “It’s rare to see the whole country interested in the same animal.”

In Dương’s drawing, a tiger is stretched on the floor of a cage. Its legs are splayed, red Xs cross out its eyes and its tongue protrudes inert.

“Raising industrial tigers for meat is not an art, but a crime,” she continued in her post. “These tigers are raised for meat … they care if it’s heavy, not if it’s healthy.”

Hoài Lê, Nguyễn Cẩm Anh, and Jeet Zdung are a disparate group of artists who, like Dương, have made endangered creatures central to their work.

Lê volunteered to draw murals of turtles on An Binh island during an event in 2017 held by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Vietnam is home to 25 species of turtle, two of which can’t be found anywhere else in the world. The effort sought to raise local and tourist awareness in protecting marine turtles.

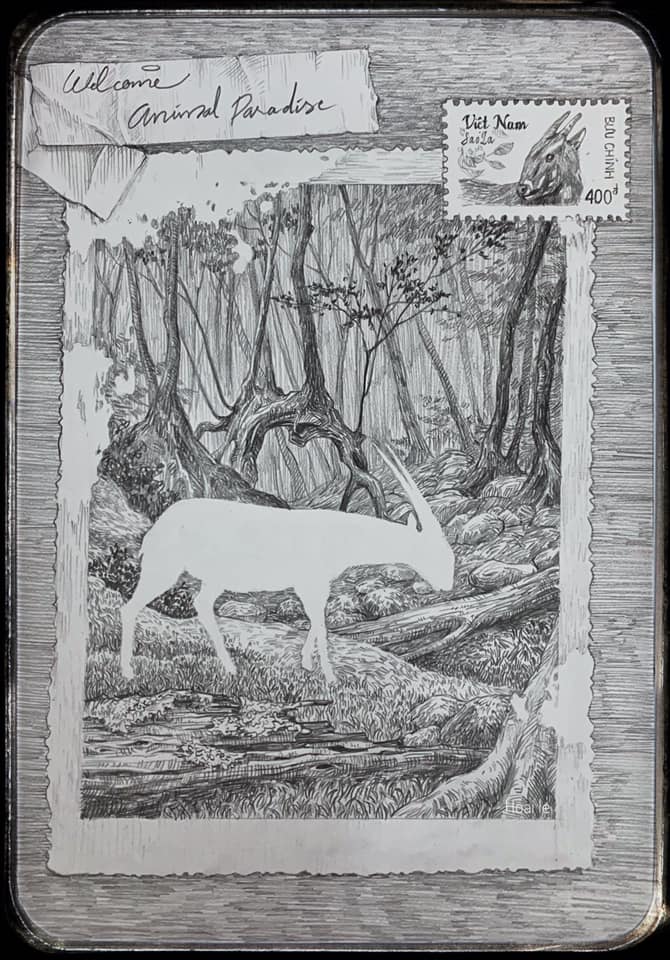

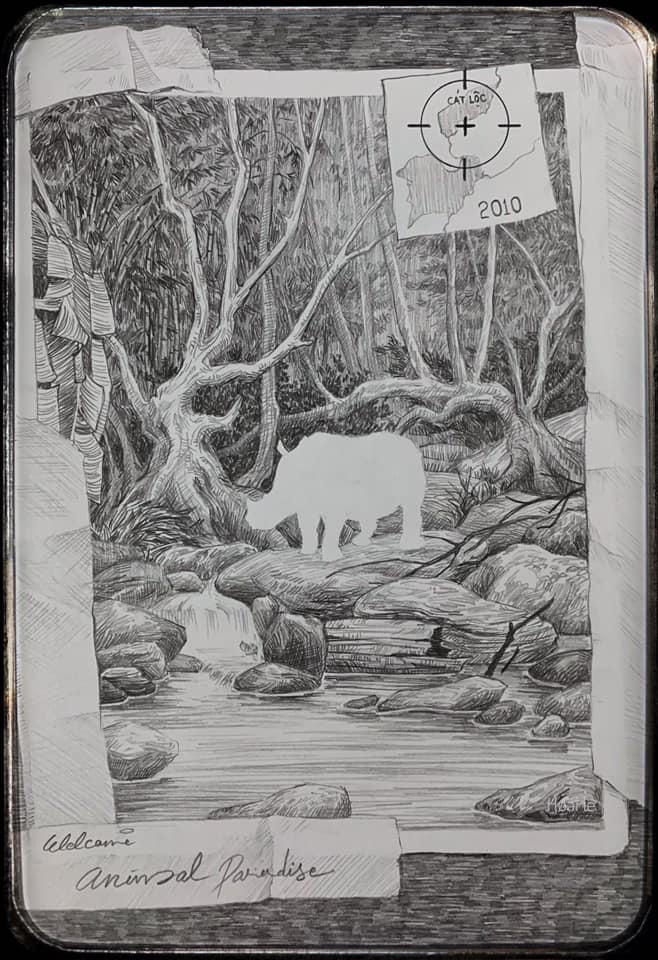

Ever since Lê volunteered on the island, she has continued to centre her illustrations on the country’s critically endangered species and some, like the Javan rhino, which have already disappeared completely in Vietnam.

“The last Javan rhino in Cat Tien National Park died from a bullet. He suffered a slow, painful death, which terrified me,” Lê told the Globe of Vietnam’s last rhino found shot and with its horn removed in 2010. “Using endangered animal products is popular in Vietnam. Some of my friends still sell snakes, squirrels, foxes, and wild animal meat.”

Lê depicted a rhino and the critically endangered saola – a forest dweller known as the ‘Asian unicorn.’ The landscape is intricately detailed while, in contrast, the animals’ forms are silhouetted in white.

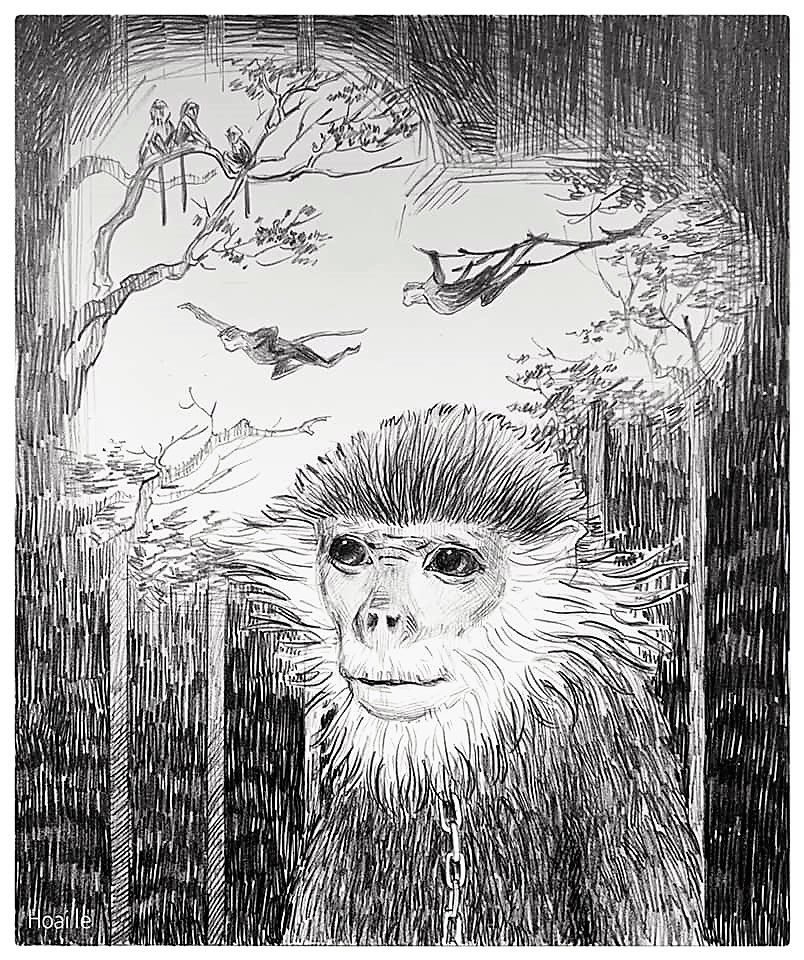

During Vietnam’s worst wave of Covid-19, which emerged in late April, Lê has been living in a small room in Ho Chi Minh City, which has been under total lockdown since the end of August. Feeling trapped, Lê began to think about caged wildlife and drew a series of six animals confined as pets.

“I have to stay in a tiny rented room, which makes me feel suffocated and super uncomfortable. It makes me think about caged animals,” she said. “In Vietnam, it was very rare to keep wild animals as pets, but recently the young generation started to keep turtles, illegally imported iguanas and frogs. Adults have birds, monkeys or other primates as pets.”

With the rise of social media in Vietnam, wild creatures are also easily purchased online and keeping them as pets is sometimes seen as a quirky hobby.

“I am strongly opposed to keeping wild animals as pets because, obviously, their wild environment is nowhere comparable to a caged environment. They will be harmed, lose their freedom and being cut off from their species must be very lonely,” she said.

“I do believe the arts can attract the public’s attention.”

Professional illustrator Cẩm Anh followed a similar path to featuring vulnerable animals in her work. In 2014, she came across the NGO Animals Asia, which was collecting signatures for a bear protection facility in northern Vietnam’s Tam Dao National Park. She has collaborated with the NGO since and is working on animated videos as well as botanical illustrations of medicinal plants, which can be used to replace bear bile in traditional medicine.

Art is a way to convey information directly and to reach emotions

“I was always an animal lover but felt that I was not good enough to be a vet or researcher,” she told the Globe. “I realised drawing animals in Animals Asia’s campaigns is also a way to protect animals.”

“Art is a way to convey information directly and to reach emotions,” she said.

There are two species of bear in Vietnam, Gấu chó and Gấu ngựa, or the sun bear and moon bear. Both vulnerable, only a few hundred are left in the wild in Vietnam. Bile is often extracted from the bears’ gallbladders for use in traditional medicines, although this practice has been banned since 2005.

A Ho Chi Minh City resident told the Globe she saw this practice firsthand while working at a zoo outside of the city. Although she wanted to share her experience, she did not want her name used due to concerns about her safety.

After graduating from veterinary school eight years ago, she took a position at the zoo. A couple of weeks into the job, the head vet asked the staff to gather in an area where moon bears were kept in small cages. The manager told them they would be tasked with extracting bile from the bears once or twice a month and demonstrated the procedure.

“I was shocked, I was really terrified,” she said. “I was young and innocent thinking I was following my passion and I was stuck in a mafia place.”

The young woman’s alarms had already been raised after hearing rumours that the tiger cubs she was looking after in a hidden room monitored by video cameras would later be sold for a profit. After the incident with the bear bile, she quit her job.

In late 2020, a moon bear and her cub were rescued by Animals Asia in northern Phu Tho province from a bile farm. The elder bear had been in captivity for 18 years.

From what I know, not many people know about endangered animals or it’s simply that they don’t care about it

Showcasing the impact that art could have on younger generations, Jeet Zdung illustrated the recently released children’s book, Saving Sorya: Chang and the Sun Bear.

The book is based on the early life of its author – the well-lauded conservationist Trang Nguyen – telling the story of how a young Vietnamese girl became an animal rights activist after witnessing a bear being tortured.

An animal enthusiast from a young age, Zdung told the Globe that he would draw animals and write down their features in a big notebook after watching Animal World on television.

Now, Zdung has been able to fulfill his childhood dream while helping raise the awareness needed to keep Vietnam’s at-risk animals from disappearing completely.

“I believe that comics and movies are effective ways to spread messages and knowledge about the incredible animals that are on the dangerous edge [of extinction],” he said. “From what I know, not many people know about endangered animals or it’s simply that they don’t care about it.”

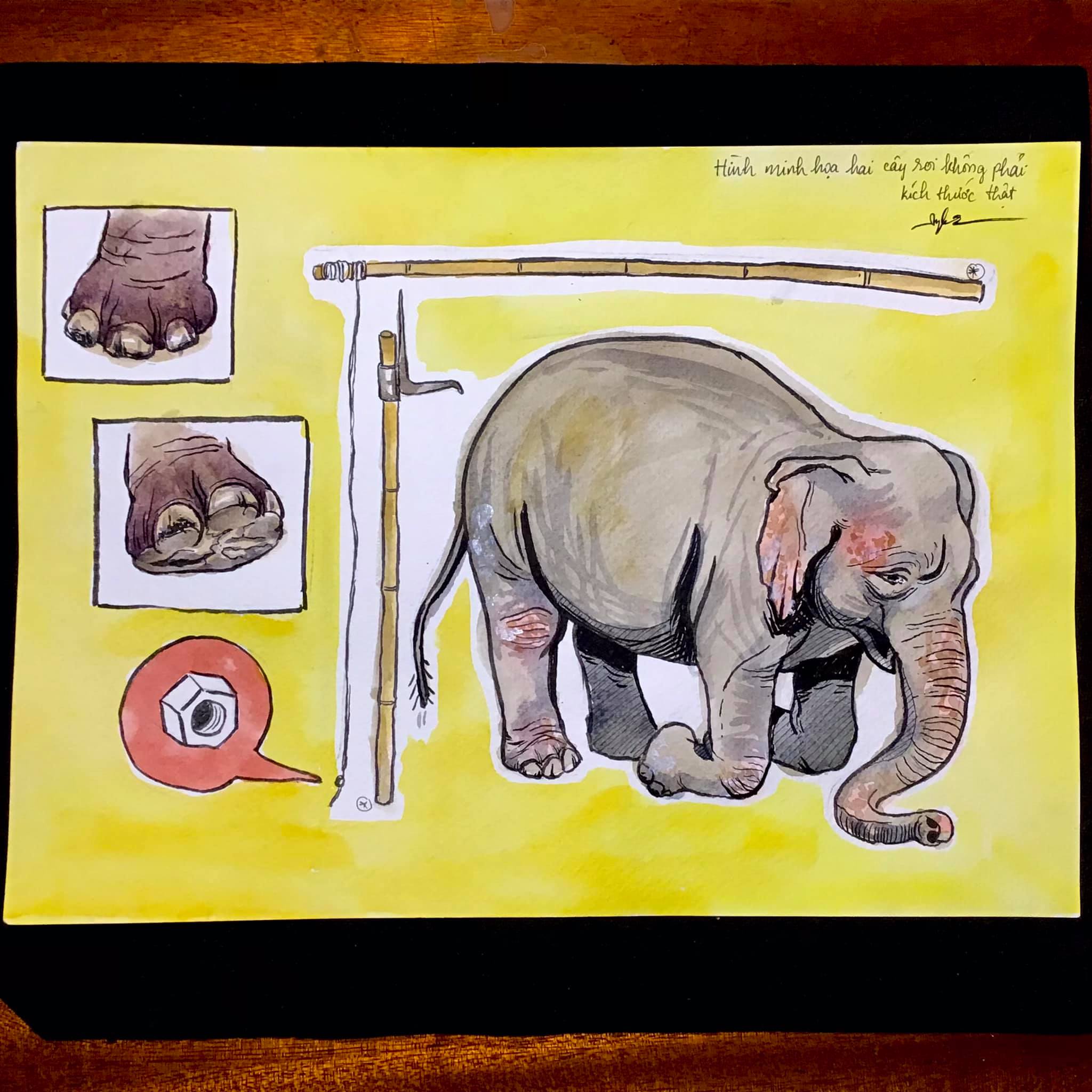

Nguyen and Zdung are working together on another book set to be published in 2022, Saving H’non: Chang and the Elephants. With a similar focus on the mistreatment of animals, the story follows the lead character’s attempt to free an elephant forced to work for logging and tourism companies. It is estimated that there are just between 60 to 100 Asian elephants living in the wild of Vietnam’s Central Highlands.

Zdung said he does not want to see endangered animals go extinct and drawing comics and illustrations is the best way he can contribute his capabilities to wild animal conservation.

He and the other illustrators offer different interpretations of their subjects – from Lê’s rhino and saola silhouettes to Dương’s alarming depiction of a tiger – but they share the common vision of using their art to help preserve Vietnam’s at-risk species.

“I’m simply in love with them and don’t want them to disappear,” Zdung said.

This article was updated on 13 October 2021.