Singapore has a growing ageing population facing difficult conditions. They are living in smaller family units, increasingly scattered abroad, amongst things we often ignore including Covid-19, the climate crisis, failing health and mental illness.

By 2030, 25% of Singapore’s residents will be older persons, according to Charlene Chang, the Ministry of Health’s group director of the Ageing Planning Office.

An ageing person often is puzzled by ‘end-of-life’ decisions, especially after retirement. My own thoughts imagine those years as a journey from my bed to a hospital bed, which more or less sums up the choices for Singapore’s older population – either you live at home or you go into a hospital ward.

We should have more options for those in-between years. This requires a public discussion of infrastructure for the daily lives of older people including housing, services, socialising and purpose.

While it is easy to pin this on the ‘system’ or the ‘government,’ it is really up to us to own our plans as we become older persons ourselves. What do I do? What documents do I finalise? Who can I depend on? Do I know who I am and what I like?

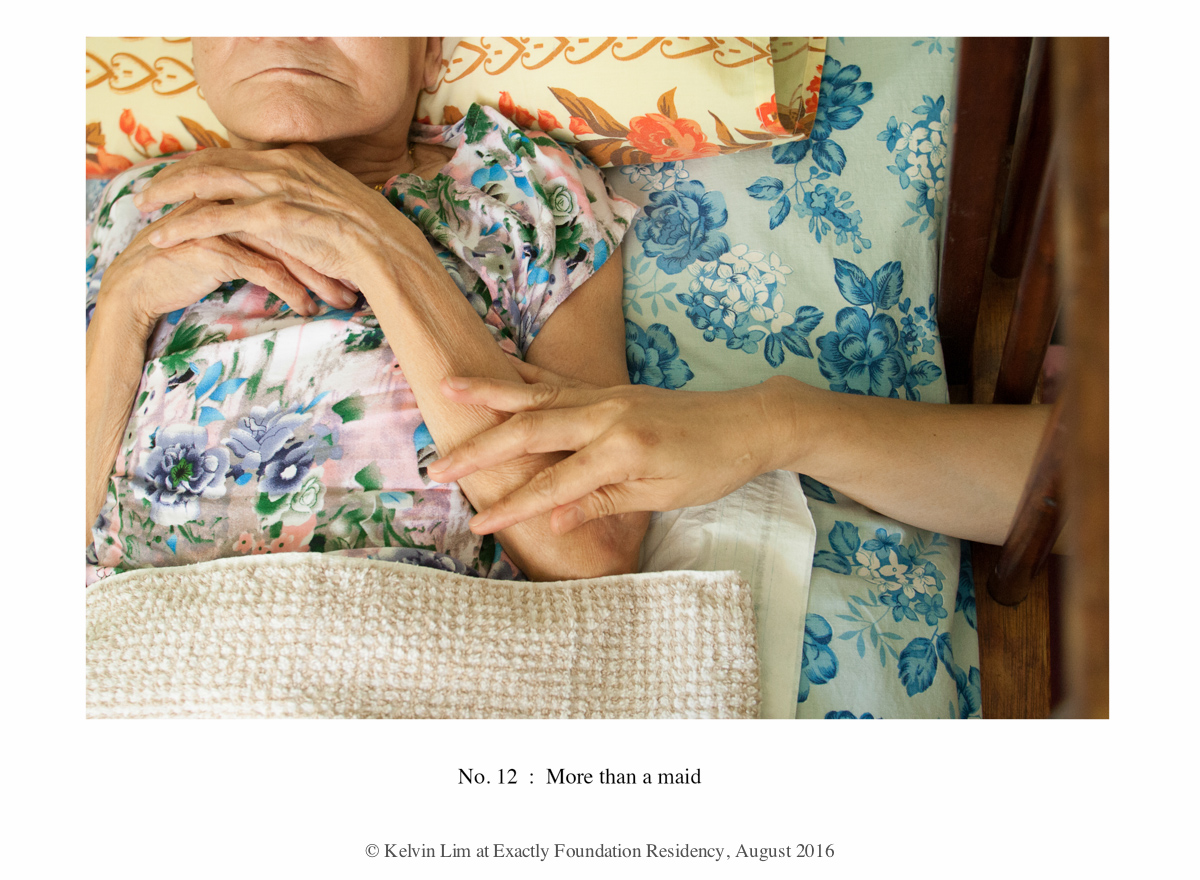

We should also consider the other looming unknown of what happens to someone acting as a caregiver and then ageing into their own inadequate support. As we live longer, older people are often caring for other, even older people. The caregiver’s role usually falls to a female relative or hired help.

This long spectrum of needs and care was visualised through my Exactly Foundation projects, as well as my own experience living in Singapore and caring remotely for my mother in Taipei.

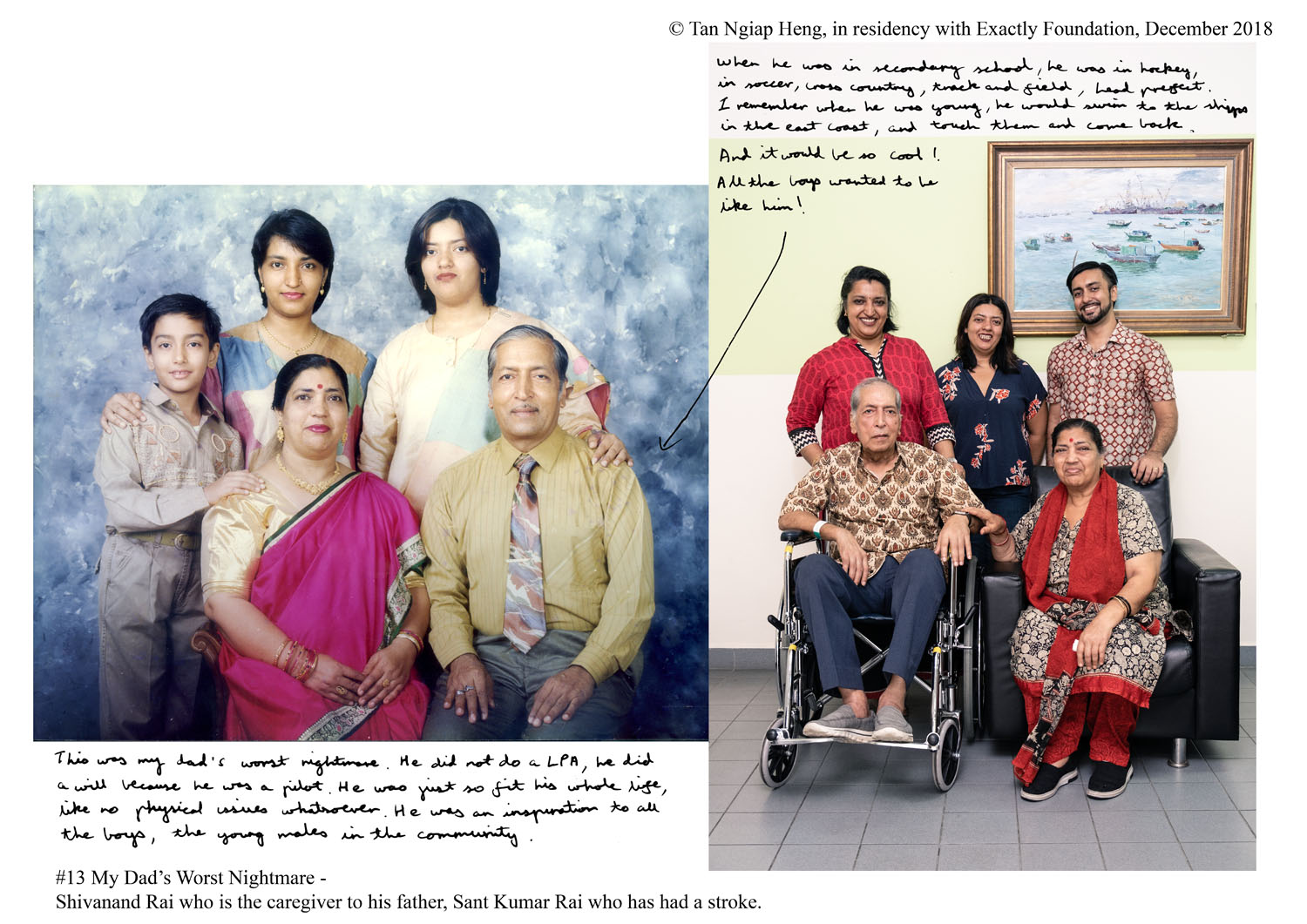

The Exactly Foundation, a nonprofit promoting photographic work stimulating discussion about social concerns in Singapore, commissioned Kelvin Lim in July 2016 to create an artwork titled, ‘Who Cares?’, and in December 2018, Tan Ngiap Heng was commissioned to make ‘Holding Space’.

Ngiap Heng’s father and my mother would pass away in 2019 in the midst of the ‘Holding Space’ project, making the reflections even more profound. While their deaths were expected but sad endings, the long, preceding years were frustrating and fearful, mostly because as their children, we fumbled about the best courses of action as their diseases progressed. Did it have to be this way?

I wondered about my mother, why didn’t / couldn’t she plan better, face up to the issues and death? Well, she just didn’t like it.

My mother lived in Taipei and I was in Singapore, so I outsourced her care. This experience taught me about different types and perceptions of care. That finding the best person to take care of my mother was itself a way of showing my concern for her. But I still ask myself, did I do everything a good daughter should?

Over time and because of her immobility, my petite mother expanded to 67 kilograms (147 pounds). I was not strong enough to do the frequent lifting between her bed and wheelchair required for nearly ten years. Yet I convinced myself that despite her advanced dementia, she acknowledged my presence by flickering her eyelids and moving her mouth. That was the entire extent of our communication during those years.

When my mother developed breathing difficulties in late 2018, she went into a hospital intensive care unit and had to undergo a tracheostomy, which involves cutting an opening below the vocal cords to intubate the windpipe for air to directly enter. The procedure is considered uncomplicated, normally taking 15 to 20 minutes, but she was in surgery for an hour; the last 30 minutes of not knowing the progress of her surgery was excruciating.

The big question from the medical staff was always, “Do we resuscitate?” They said she was so old and resuscitation is so aggressive that it would damage her. Death is a topic our mother refused to talk about. We finally gave permission to resuscitate and I added, “at least once.”

I thought very hard, not about what I personally wanted, but what our mother would have wanted and what I remembered of her. While we were growing up, our mother would go all out to preserve life, for herself and her loved ones. One sniffle and an aspirin tablet would appear. She had not gotten to 100 ignoring illness and she would have wanted us to try to resuscitate her.

My mother was a devout Christian, daughter of a pastor, married to a pastor. She believed dying involves going home to heaven, to God. And yet she had great discomfort in her journey getting there, the pain of ill health and treatment, the pain of loss and the pain of not seeing her children, grandchildren and great grandchildren. I often wonder if she could change and take comfort in the possibility of once again seeing the people she loved who had passed on.

I believe it is natural to live and to die. From the moment we are born, we are already expiring. Yet there is so much living to do, which is so consuming that we don’t want to think about death. I admire my mother for her tenacity, stamina, love of food and just plain goodness. I want to be like my mother, but I also don’t; I want to be better prepared.

End-of-life preparation adds to faith and gives us more headspace to enjoy living. For me, it also removes the confusion, mystery and unsolicited help I try to provide my son, who lives overseas. My attempts to minimise any fumbling he might do gives me peace of mind.

Yet I find Singapore social welfare policies lack options for individualised planning; the assumption is immediate family is the primary port-of-call. This does not take into account situations in which an older person doesn’t have family in Singapore, live in private housing or have access to a licensed caregiver.

Li Li Chung is the founder of the Exactly Foundation.

Kelvin Lim, a commercial photographer and accomplished painter, was the winner of the Best Portrait Photography 2016 award (Singapore Tatler). He has exhibited solo at Portraits of Love by the Home Nursing Foundation.

Tan Ngiap Heng originally studied engineering but started working in the arts in 1995. He was a programmer at The Esplanade and then a professional photographer since then specialising in the performing arts. He has exhibited his photography and installation works. In recent years, he mooted the Work In Process project which documents the rehearsal process of dance and theatre companies in Singapore as they prepare for production.