Laos, a country once named Lan Xang or ‘the land of one million elephants’, has a strong historical and spiritual bond with the pachyderm. While the country was once known for its herds of elephants, the outlook for the population is now bleak.

About 9,000 people currently live on the income generated by some 400 domesticated elephants, primarily in the logging industry. Working hard to earn their keep, elephants pull and carry logs for a sector that is destroying their natural habitat and ultimately leading to their slow demise.

Commercial logging in Laos, a mountainous, poor, and sparsely populated country, has helped reduce the country’s forest cover to 40%. While Laos has employed logging moratoriums and cut back on and postponed logging quotas at various points in recent years, the survival of the species in the wild is seriously endangered. Home to between 300 and 600 elephants, the country’s wild elephant population is plummeting at an alarming rate, with some estimating that at their current rate of decline, they could be extinct within 50 years.

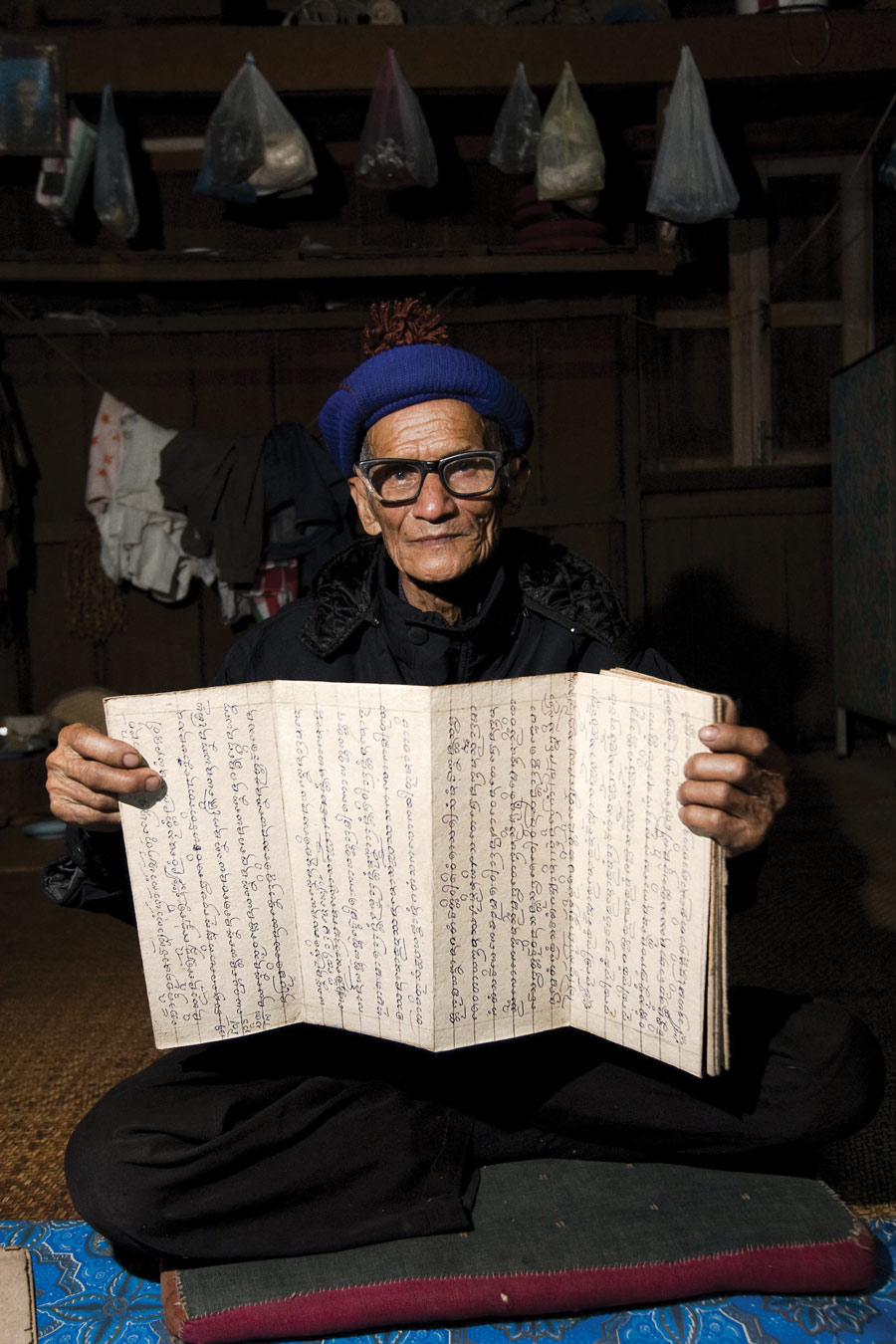

Traditionally, elephants from wild populations were captured and domesticated by skilled mahouts. In the past, elephants were employed for two or three hours a day to bring rice from the harvest, to carry firewood and to help build houses. Now they are employed in logging camps and typically work at a furious pace for eight hours a day. The elephants are overworked, exhausted and isolated from each other, and therefore unlikely to reproduce. For every two births there are ten deaths among the domesticated population, and if this trend remains unchanged, domesticated elephants are likely to disappear by 2060.

Many conservationists hope that a well-managed tourism industry may offer a way to regenerate the stock of captive elephants, by giving owners cash incentives to allow female elephants to breed. The tourism route is appealing for many owners, some of whom risk their and their elephant’s safety and endure long-periods of isolation to extract valuable hardwood from remote hillsides.

While it remains to be seen if logging bans and tourism will provide enough of a respite for elephants to revive their population, it is clear that unless something changes, Laos will likely become the land of no elephants.

Brent Lewin is a Canadian photographer based in Bangkok. His work has been featured in publications such as National Geographic, The New York Times and Newsweek. Pictures of the Year International, Px3, the International Photography Awards and American Photo have awarded his ongoing documentary work on the vanishing culture of elephant keeping. Photo District News (PDN) also selected Lewin as one of the PDN 30 photographers in 2010. More of his work can be viewed on his site: brentlewin.com