For Diep Nguyen, life in Vietnam is good. The 32-year-old entrepreneur is a native of Ha Long, a rapidly changing city on the northeast coast known for the karst-studded bay with which it shares a name.

She now lives in Ho Chi Minh City, where she helps oversee several popular Airbnb properties in the booming commercial centre.

“The job opportunities in Vietnam are quite good,” Diep said. “I didn’t come from a very big city, and I had a normal education. I started studying English in sixth grade, but it wasn’t very proper. A lot of my friends were like that, and we’re turning out well.”

Meanwhile, chronic problems associated with a fast-growing city, such as relentlessly expanding urban sprawl, traffic which grows denser by the day, routine flooding and worrying air pollution, are seen as minor hindrances.

“Of course the traffic and the pollution are annoying in some ways, but it’s just something you have to deal with,” she said. “I’m a positive person.”

Diep’s upbeat outlook on Vietnam jives with recent findings in a study on the quality of life of earth’s more than 7 billion inhabitants, in which the country performed unexpectedly well.

The wide-ranging study, called A Good Life for All Within Planetary Boundaries, published by a group of researchers from the University of Leeds, argues that we need to dramatically rethink the way we view development and its relationship to the environment.

One of the study’s authors, Dr Andrew Fanning, a Marie Curie Research Fellow at the university’s Sustainability Research Institute, explained how his team undertook the study.

“We were essentially working on several different indicators and relationships between social outcomes and environmental indicators,” Fanning told Southeast Asia Globe. “We came up with the idea of, well, if we’re looking at social indicators, can we define a level that would be equivalent to a good life?”

The researchers settled on 11 social indicators that included life satisfaction, nutrition, education, democratic quality and employment.

“The next question was, what is the level of resource use associated with achieving those basic needs, and how does that then compare to what is environmentally sustainable?” said Fanning.

The researchers established seven biophysical boundaries against which they measured the social indicators – things like CO2 emissions, material footprint and blue water. In the scientific community, maintaining healthy limits in these areas is considered key to ensuring a sustainable planet moving forward. Essentially, meeting human development goals is meaningless if they come at the expense of the very environment we live in.

“It did surprise us that Vietnam did so well overall. You might expect it to be Costa Rica or Cuba, as Vietnam doesn’t typically come up as a sustainability hero”

Dr Andrew Fanning

The team gathered information on 151 countries, leaving out any with a population of under a million and those without sufficient data. In the end, Vietnam was the most sustainable country. This means it provides the most social benefits while doing the least environmental damage.

To be clear, these findings do not show that Vietnam provides the best quality of life in the world. In fact, according to the research, no country currently has a sustainable way of improving the lives of its people. Germany, for example, met all 11 social indicators, but it also failed at five environmental boundaries. Such a result suggests that the development model of highly industrialised nations is not the way forward, and developing countries need to find a new path if they hope to offer a sustainable livelihood.

The findings also set up an intriguing political debate in an era when the dominant liberal democratic model faces scrutiny around the world. By and large, the countries that performed best socially but worst environmentally are advanced democracies, while Vietnam is a single-party state that scored poorly in terms of democratic quality.

“It did surprise us that Vietnam did so well overall,” Fanning said. “You might expect it to be Costa Rica or Cuba, as Vietnam doesn’t typically come up as a sustainability hero.” Fanning was referring to two countries the researchers expected to do well since they generally provide good social support and haven’t seen the same environmental damage many countries have.

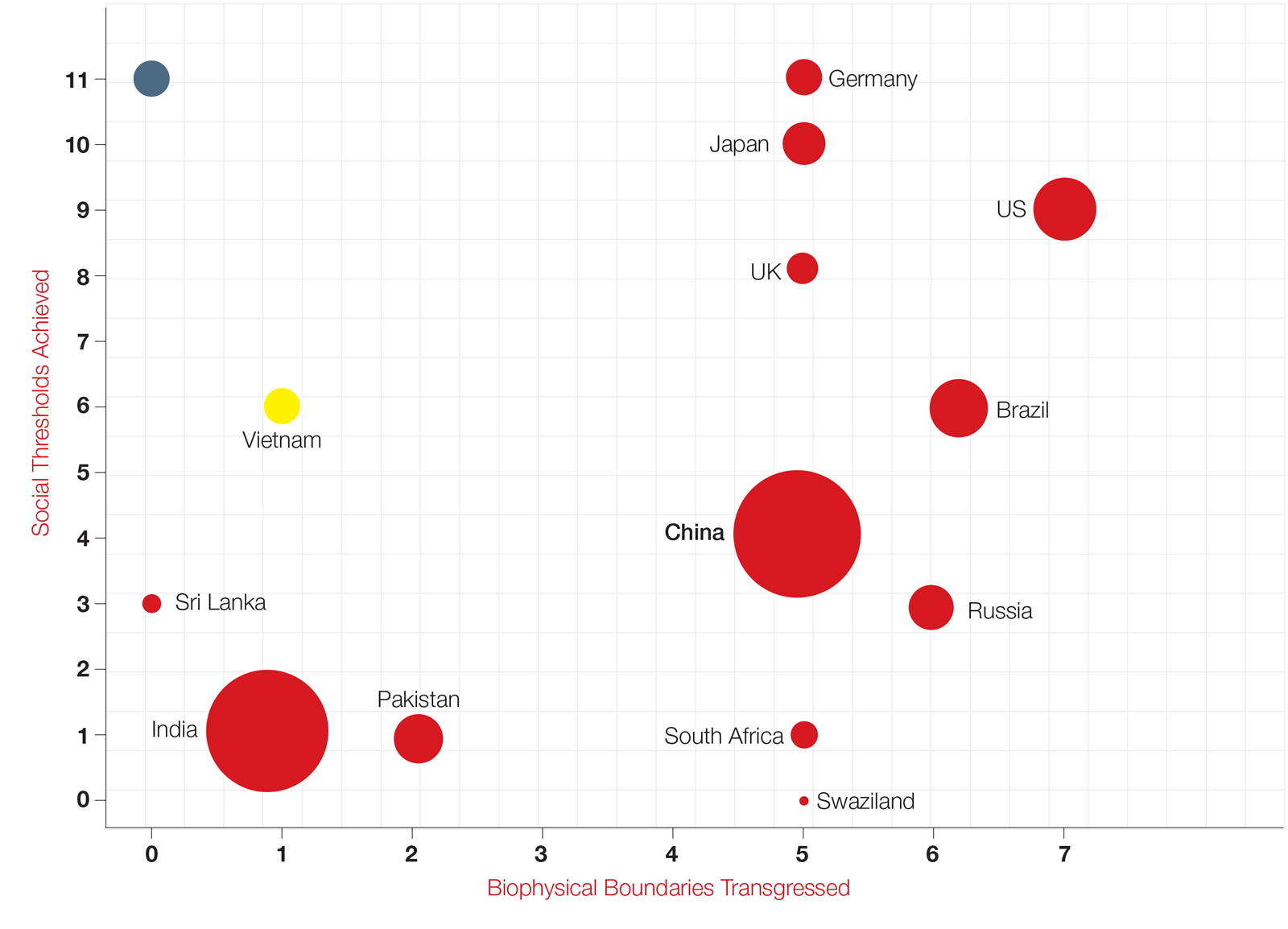

Good Life in Planetary Boundaries

This table depicts social thresholds achieved against biophysical boundaries transgressed. The ideal sustainable country is represented by the gray circle in the top left corner.

Indeed, national media routinely tell stories of deforestation, industrial pollution and mountains of plastic waste, issues that have a sharp impact on the daily livelihoods for many. At face value, these problems don’t portray a sustainable nation, but by taking a close look at the methodology behind the research, one can get a sense of how Vietnam fared so well.

Fanning’s group used a consumption-based method for the environmental indicators. “This means that if Vietnam is producing goods and services which are then exported, the environmental degradation related to that production is not attributed to Vietnam; it is attributed to wherever those goods and services are consumed,” he explained.

This presents a huge advantage for Vietnam, which is an export powerhouse across sectors such as agriculture, textiles and electronics. According to MIT’s Observatory of Economic Complexity, in 2016, Vietnam exported over $207 billion worth of goods, largely finished products like smartphones and televisions. Samsung alone ships millions of made-in-Vietnam phones globally every year – yet, under this methodology, none of the associated environmental damage falls on Vietnam.

Fanning added that it is also important to keep in mind that the study has a global focus: “The planetary-boundaries framework is meant to look at tipping points for the earth system as a whole, so it doesn’t really capture local environmental-quality issues. What the framework argues is that now we’re at a point where the human enterprise is so large on a global scale that we need to start talking about planetary impacts, as well as local.”

This goes against the national-level goals preferred by many countries, like the United States, with its current resistance toward global agreements on climate change. The research stresses that the development path followed by the US and many European nations has been a failure, both for Earth and the people living on it. The complete unsustainability depicted through this research of Germany, a country widely viewed as an eco-friendly icon, highlights the vast shortcomings of modern development theory.

One final caveat to keep in mind, particularly in regards to Vietnam, is that much of the data used by the researchers came from 2011. In the years since, Vietnam has largely maintained a robust annual growth rate of over 6% of GDP.

“It’s true that Vietnam has made incredible progress from the 1980s until now by lifting people out of poverty and improving access to education”

Louis Vigneault-Dubois, UNICEF

While this has created huge economic benefits for many, it has spurred rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, leading to pressing issues across sectors like the environment, healthcare and labour, meaning Vietnam’s positive performance could be in danger. It’s worth taking a granular look at some of the indicators in the study to see how they stack up on the street.

According to the World Bank, 70% of Vietnam’s population is under the age of 35. This means indicators such as nutrition, education and healthy life expectancy will be vital for the country moving forward.

Louis Vigneault-Dubois, chief of communication for the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) Vietnam, believes the nation’s strides in bettering its people’s lives are worthy of praise.

“It’s true that Vietnam has made incredible progress from the 1980s until now by lifting people out of poverty and improving access to education and so on,” he said. “I think the story there is quite clear.”

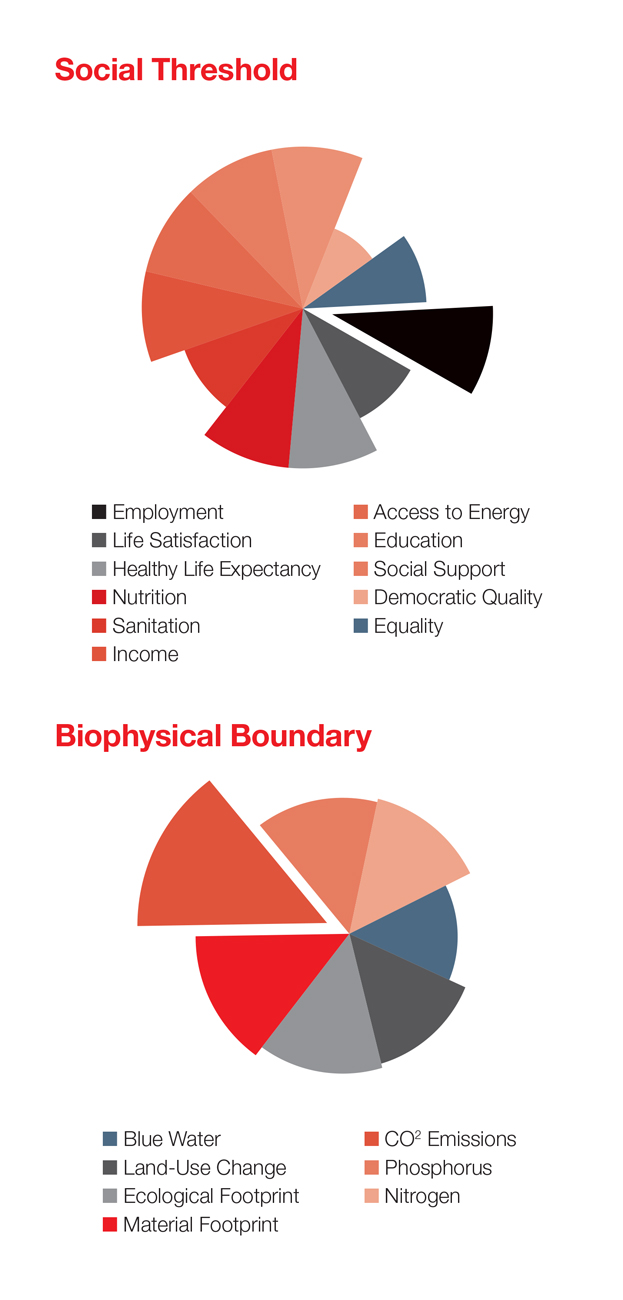

These graphs are breakdowns of the amounts of social thresholds gained and biophysical boundaries transgressed by Vietnam in the study

Vietnam is one of the world’s impressive modern economic success stories. Following the devastation of major wars against France and the United States, much of the country was in ruins, and food rationing lasted into the early 1980s. Economic stagnation and food shortages hit as a rift with China grew and the Soviet Union collapsed, spurring the introduction of a program called Doi Moi, or Renovation, in 1986. This radically altered the country’s economic structure and, along with the end of the American embargo in 1994, opened the country up to rapid economic change and growth, a run that is only now hitting its stride.

For Vigneault-Dubois, though, the story changes when you break it down by region: “What we see is that this progress has been uneven across the country. So if you’re a child from an affluent family in Ho Chi Minh City, chances are you’re probably having a good quality of life.”

Chau Nguyen, 31, recently had a baby with her expatriate husband and lives in the city. She believes that Vietnam has the resources to give children a comfortable upbringing, but only if their parents have the means to afford them. “I can see that there are now many childcare options in Vietnam because it is a prosperous country that welcomes a lot of opportunities across different industries, and especially education,” she said.

But these opportunities aren’t necessarily available to all parents. “If you have a lot of money, you will definitely go for international childcare and education,” said Chau. “There is no doubt, however, that not everyone has enough money to give their kids an international education.”

This is a particularly acute problem for people living in the Central Highlands or the mountainous far north. These rugged regions are home to most of Vietnam’s ethnic minority populations, who have been left behind in Vietnam’s impressive race up the global economic table.

There’s a gap in education, a sector that Vietnam prides itself on. “If you look at the national average, you probably have 95% of kids who are going to school, but in provinces in the mountainous regions, it drops to around 80%,” said Vigneault-Dubois. “And then if you move up to secondary school, this falls to roughly 50%.”

Nonetheless, Vigneault-Dubois believes Vietnam has the capacity to improve these indicators – but prioritising them is another matter.

Vietnam fared very well in the social support, employment and income indicators. On top of the healthy economic growth mentioned above, the national unemployment rate was 2% at the start of 2018, according to Trading Economics.

Makiko Matsumoto, an employment specialist at the International Labour Organisation in Bangkok, is generally upbeat about the country’s labour sector, though she noted a few areas of concern: “There’s an ongoing gradual shift out of agriculture and into industry and construction. What is a bit different in Vietnam compared to some other countries in Southeast Asia is that it has a high incidence of wage employment, meaning wage and salaried employees.”

This means that wages generally increase every year, a positive for workers, especially as cost of living increases annually.

“But of course it doesn’t mean everything is great,” she went on. “One issue is productivity – it is increasing, but a bit slowly, especially compared to other neighbouring countries.”

In fact, according to the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, national labour productivity is a sixteenth of Malaysia’s and a third of Thailand’s, and is even behind less-developed economies like Cambodia’s.

“If you’re a child from an affluent family in Ho Chi Minh City, chances are you’re probably having a good quality of life”

Louis Vigneault-Dubois, UNICEF

Another area of growing concern, especially given the country’s increasingly prominent role as a production powerhouse, is support for unskilled factory workers. “At least anecdotally, yes, that’s a problem,” Matsumoto says. “I think there is an issue of [training] workers, particularly while they’re working. Otherwise, by the time you get married and you’re 30 years old, then either you’re fired or you quit anyway, and if you try to come back later, you won’t have the right kind of skills or abilities to do new things.”

While Vietnam was the most sustainable country in the study, Fanning, the researcher, was disheartened by the fact that it is still not as sustainable as the researchers had hoped for.

“To me, the biggest take-home message from this paper is that there is no country who is achieving basic needs for its citizens at a sustainable rate of resource use,” he said. “We’ve been talking about Vietnam doing the best, but really they’re not doing very well… So what that says to me is that there really is a need for a fundamental restructuring of how we achieve basic needs if we hope to not surpass critical environmental boundaries.”

So according to Fanning, the human species needs to rethink the way we improve our daily lives – or risk planet-wide ecological disaster.

For Chau, this way of thinking means being flexible when it comes to raising her daughter in Vietnam: “For her growing up, we are considering letting her spend her childhood here, where she can understand her own country, both the good and the bad. But for her future education, we are considering letting her have the chance to learn in the best education systems, either in the United States or other foreign countries.”

Both Diep and Chau are content – for now, at least – with taking Vietnam’s positives, along with the negatives. As the new mother said, “No country is perfect.”