This op-ed was written on behalf of Rimba, a group of scientists who conduct conservation research to produce evidence-based management recommendations that will help decision-makers mitigate threats to biodiversity in Peninsular Malaysia.

A rock, is a rock, is a rock. Or is it?

Hard to believe, but we owe our lives to white craggy rock formations. On this International Day of Biological Diversity, we’re giving thanks to these rocks.

Why? Because these rocks built our deep appreciation for nature. They built our careers as conservation scientists. They even helped build our homes!

Millions of people across the globe, and particularly in Southeast Asia, are also indebted to towering formations of this amazing rock known as limestone karsts – and most don’t even know it.

We’re all indebted to limestone for the water we drink, the rice we eat, the durians we enjoy, the scenery we marvel at, and the homes we live in.

Caves in limestone karsts provide tonnes of bat guano for farmers to nourish their crops. They also shelter millions of insectivorous bats that keep mosquito populations and their associated diseases in check, and help devour crop pests to save farmers millions of dollars on artificial pest control.

They also shelter fruit bats that pollinate commercially important fruit trees such as durian, which generates millions of dollars for economies around the region. Without caves, there will be fewer bats, and fewer durians to supply the region’s insatiable demand for the ‘King of fruits’.

Breathtaking caves are also used by people to house religious deities in countries such as Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam. Millions of Buddhists and Hindus use them as sanctuaries for worship throughout the year.

Limestone karsts have also become major attractions for the region’s multibillion-dollar tourism industry. They have been a staple backdrop for many island destinations in Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam, some of which are recognised as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

When limestone outcrops become watery graves, there is a more intangible cost – the extinction of unique organisms that no amount of money can ever bring back to life

In Hollywood, these oddly shaped rocks have somehow captured the imagination of movie producers for James Bond: Tomorrow Never Dies and Kong: Skull Island. Visit Halong Bay in Vietnam, and you’ll see why.

Who would’ve thought that theme parks also owe their income to the gorgeous backdrops and natural hot springs that limestone karsts provide? If not for these tourism values, limestone quarries might already be in these places.

But limestone quarries are necessary. Without them to make cement, no concrete buildings would exist. The problem is, when a limestone outcrop gets completely quarried away, this piece of rock ceases to provide invaluable ecosystem services to people living around it.

When limestone outcrops become watery graves, there is a more intangible cost – the extinction of unique organisms that no amount of money can ever bring back to life. And this brings us back to our story on how this piece of rock shaped our formative lives.

Children typically collect stamps and coins as hobbies. Well, the both of us were slightly different: we were shell-collecting geeks.

Before we met each other, both of us spent our teenage years independently visiting limestone karsts all over Malaysia to look for new species of snails. This hobby actually trained us to become malacologists – scientists who study molluscs.

In 2008, during a research survey at a limestone karst in Malaysia, we hit gold – in the figurative sense.

We discovered an alien-looking land snail species entirely new to science. It was so outlandish, so mind-blowing, that it got featured by the New York Times, and was voted by Arizona University’s International Institute for Species Exploration as one of the world’s top 10 species discovered in 2009.

Meet the worm-like snail Whittenia vermicula, named in honour of the late Dr. Tony Whitten, a staunch advocate for limestone biodiversity conservation, and a nurturing mentor who set us both on a long and winding road to help save limestone biodiversity from extinction.

Land snails are just one group of living creatures that have made limestone karsts in Southeast Asia globally outstanding. Caves in Thailand, for example, are home to the smallest mammal in the world – the bumblebee bat (Craseonycteris thonglongyai).

Dubbed “the Galapagos Islands on land”, limestone karsts have been a favourite target for hobbyists and glory-seeking scientists when it comes to species discovery. On a piece of rock, some no larger than the size of a car park, one can find unique species found nowhere else on the planet. But why?

It has something to do with the Galapagos analogy. Like the archipelago made famous by Charles Darwin, Southeast Asia’s limestone karsts have become modern-day terrestrial islands scattered and isolated from one another after millions of years of weathering and erosion. Indeed, they were once massive blocks of reefs beneath ancient seas before they were uplifted by tectonic events.

Plants, fish, frogs, insects, lizards and snails that can only move limited distances often make limestone karsts their permanent homes. So over millennia, these organisms have evolved into distinct species

Plants, fish, frogs, insects, lizards and snails that can only move limited distances often make limestone karsts their permanent homes. So over millennia, these organisms have evolved into distinct species, and became restricted or endemic to one or a few limestone karsts only.

Yet despite the obvious importance of limestone karsts to people across Southeast Asia, this ecosystem and its unique biodiversity remain poorly managed or even ignored in conservation plans.

On the surface of forested limestone karsts, we’ve observed overly ambitious farmers recklessly burning and clearing vegetation to plant fruit trees, despite the thin soils on limestone karsts being obviously unsuitable for agriculture.

In suburban areas, we’ve seen rubbish piled high and burned against the base of limestone cliffs, creating massive wildfires on limestone karsts during droughts, and wiping off large swathes of limestone forests. Some limestone organisms are so intolerant of dry environments that they cease to grow without sufficient humidity, let alone survive a burning inferno.

In limestone caves, many organisms are also sensitive to disturbance, having lived their entire lives in stable dark environments to the point where some have even lost their eyesight. The opening of caves for mass tourism or conversion into temples and resorts can result in species extinctions if the wrong limestone karst is chosen for development.

Ultimately, it’s a question of which limestone outcrops the government chooses for development. Some need to be sacrificed for cement quarries – after all, without this crucial ingredient, we won’t be able to build stable structures and buildings. But how should governments decide?

It’s high time to develop a science-based approach to prevent ourselves from killing the goose that lays the golden egg. In Malaysia, we’re trying to do just that.

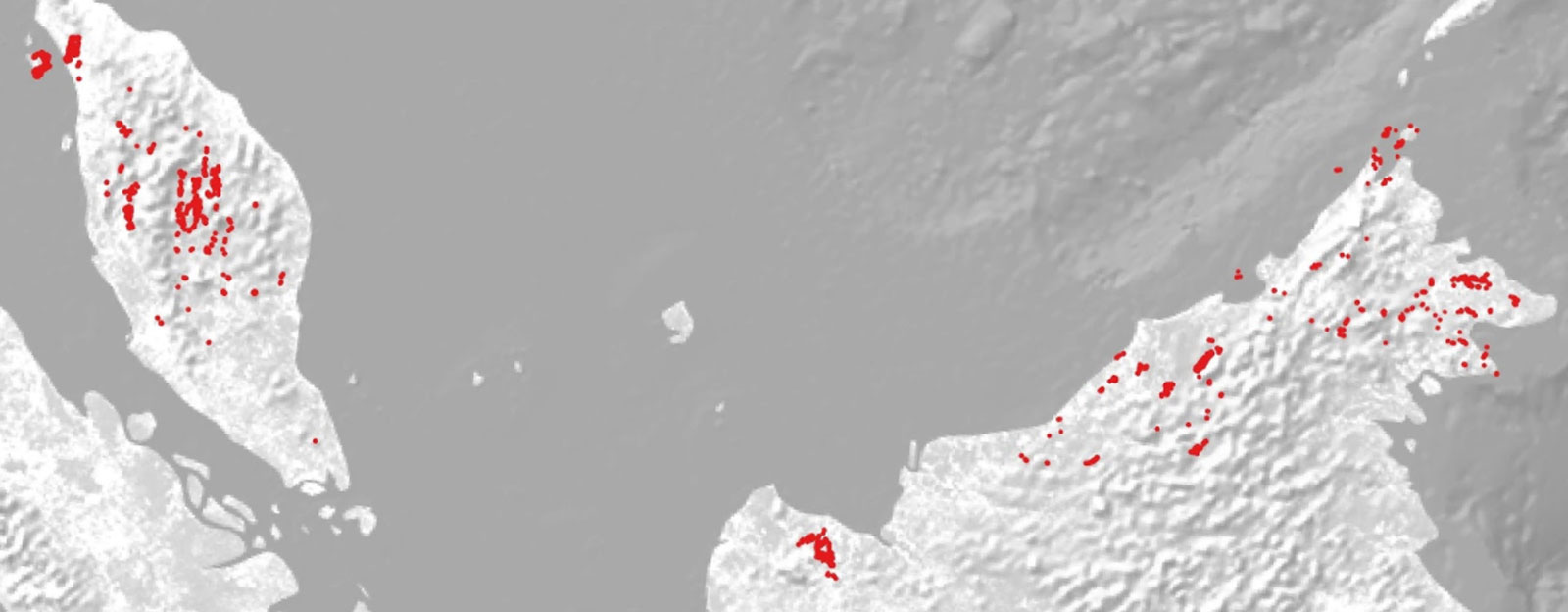

You can only conserve what you know. Prior to 2016, nobody knew how many limestone outcrops there actually were in Malaysia. So we turned to satellite imagery from Google Earth to visually cross-check limestone outcrops identified from previous studies and mapped 445 limestone outcrops in Peninsular Malaysia from the seat of our chairs.

Fast forward to 2020, we’ve now doubled that number through our on-ground surveys armed with just a GPS and a drone. This was done through collaboration with the Malaysian federal government, local universities, and our local NGO Rimba.

With a baseline map for the whole of Malaysia completed, we’re now able to conduct a science-based prioritisation exercise to identify limestone outcrops that should be set aside for conservation due to their importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, and which karsts can be sacrificed for development. This makes decision-making a whole lot easier.

We are also developing a National Limestone Conservation Roadmap for Malaysia, which details objectives and activities for the public and private sector to better manage limestone karsts. Limestone karst or cave mapping projects are also being undertaken by various researchers in Myanmar, Thailand, Timor-Leste and Vietnam.

In Malaysia at the grassroots level, limestone karst enthusiasts from cavers to biologists, teenagers to retirees, have formed non-governmental organisations to advocate and promote the appreciation and conservation of limestone karsts and their biodiversity.

All across Southeast Asia, interest in limestone karst research is increasing. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, tireless researchers have been scouring limestone karsts to discover, publish, and share biodiversity information to further the conservation of rare and endemic organisms on limestone karsts.

We’re heartened that more people are beginning to recognise the immense value of this rock, and are working towards becoming better custodians of these unique natural landscapes and their biodiversity.

Sometimes a rock isn’t just a rock – some rocks are actually worth fighting for.

Dr Gopalasamy Reuben Clements is an Associate Professor with Sunway University and co-founder of Rimba. He has 15 years of conservation research and management experience in forest ecosystems that include limestone karsts.

Junn Kitt Foon is a researcher with Project Limestone in Rimba. He researches land snail taxonomy and biogeography. He is also involved in conservation planning and management for limestone biodiversity and their habitats in Malaysia.