In the coastal city of Danang, restaurant owner Bui Tuan Lam filmed himself preparing a bowl of noodles. In the video shared to Facebook, Lam slices meat, sprinkles chives and carries a soup bowl to a plastic table in the dance-like style of influencer chef Nusrat Gokce, or “Salt Bae.”

The noodle seller, who titled himself “Green Onion Bae,” was parodying the lavish meal Gokce served to Vietnam’s Minister of Public Security General To Lam. After attending the COP26 climate change conference in Scotland in November 2021, To Lam headed to London where he was photographed eating a gold-encrusted steak sold for approximately $2,000.

The pricey excursion was widely criticised and Bui Tuan Lam was taken into police custody after his mockery went viral. In September, he was charged with “spreading anti-state propaganda.”

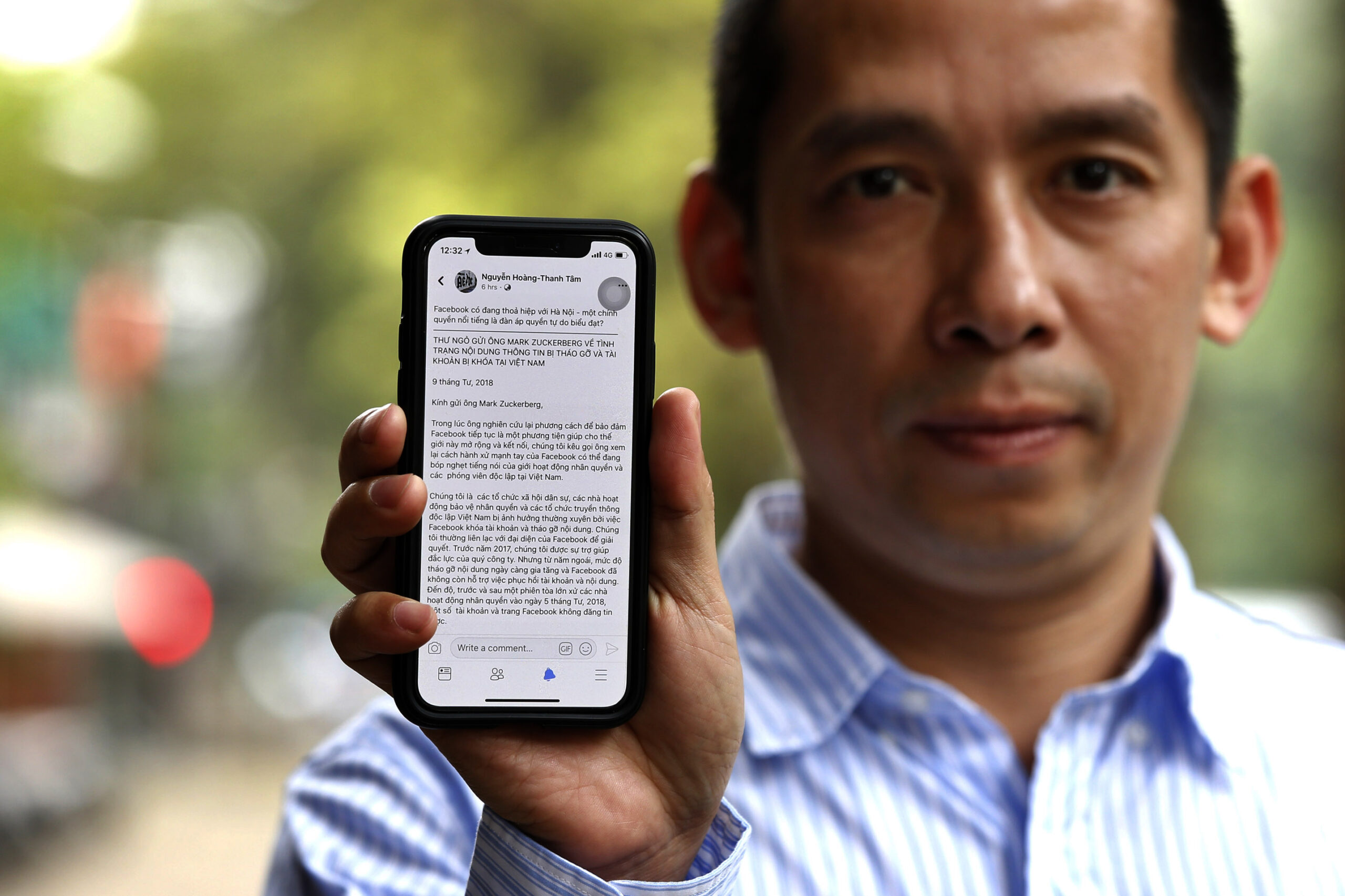

Lam’s case is not unique. Many Vietnamese who voice online critiques of politicians or government policies are arrested and sometimes jailed on similar cyber charges. According to The 88 Project, a nonprofit advocating for freedom of speech in Vietnam, there are 206 jailed activists in the country as of 11 November. Scrolling through their profiles, arrests are often tied to the use of blogs, Facebook and YouTube.

In September, music teacher and online commenter Dang Dang Phuoc was arrested for spreading “anti-state propaganda.” YouTuber Phan Son Tung was arrested the same month for the same charge. Tung’s two YouTube channels have since disappeared.

Since the internet became increasingly accessible in Vietnam starting in the early 2000s, the Vietnamese Communist Party has struggled to silence online dissent. In response, the government is tightening its grip on the internet. About four years since policymakers approved the Law on Cybersecurity in June 2018, the state has released a guiding decree for the implementation of the law.

The government unveiled Decree 53 on August 15. It states tech companies must store user information – including financial records, biometric data, ethnicity and political views – within Vietnam for a minimum of two years. If users post something deemed to violate government guidelines, authorities have the right to issue data collection requests.

While data privacy is not a major concern for most Vietnamese, Decree 53 will put increased pressure on vulnerable groups, according to Nguyen Khac Giang, senior research fellow at the Vietnam Institute for Economic Policy Research.

If an activist posts something considered a threat to the country’s security, the government can ask social media companies to provide that user’s information including private messages. Along with being a blatant breach of privacy, Giang explained, the information could be used against the individual in criminal proceedings.

“There will be very, very huge risks for those vulnerable groups,” Giang said, referring to human rights defenders and democracy activists. “There now would be much more risks for those working inside Vietnam.”

Decree 53 went into effect on 1 October and tech companies have one year to set up local offices and begin storing data onshore. While much remains to be seen on how data will be stored in Vietnam and how the new regulations will be enforced. Experts stated the decree showcases the political will for enhanced policing of the internet.

“The obsession with control is only growing with this particular government,” said Zachary Abuza, professor at the National War College in Washington, D.C. “They’re definitely trying to use laws, like Decree 53, to raise the stakes.”

Increased risk for activists

Since the internet and social media became popular in Vietnam, the state has wrestled with its hold on the spread of information.

In 2016, the military formed Force 47, a unit of over 10,000 soldiers tasked with correcting “wrong views” online. The unit is known to create pro-government pages and groups on Facebook and mass reports users critical of the state to get them suspended or removed from social media platforms. This October, Freedom House ranked Vietnam the fifth worst country for internet freedom in a survey of 70 countries.

Although the suppression of online speech is nothing new for the country, Decree 53 showcases intensifying efforts to regain control, according to Trinh Huu Long, co-founder of nonprofit Legal Initiatives for Vietnam.

“What happened over the past 15 years is that [the government] lost control over the flow of information via foreign platforms,” Long said, referring to the rise of social media sites such as Facebook.

“Now they are gaining it back by forcing these foreign actors to comply with local laws almost like domestic ones. Without having a free platform to voice their opinions, citizens are certainly more vulnerable.”

For Abuza the two-year period required for storing user data in Vietnam puts activists in danger. If requests for user data are complied with, he said, the government could show a pattern of “anti-government behaviour” instead of arresting a user over a single post.

Along with the potential impacts of Decree 53, a Reuters exclusive reported the government is considering implementing new rules by the end of 2022 to limit which social media accounts can post news-related content.

“They’re afraid that Facebook has become the de facto source of news for the public and they want to get people back into reading state media,” Abuza stated in response to the Reuters report. “This is a regime that clearly cares about control and increasingly cares about control.”

This is a regime that clearly cares about control and increasingly cares about control.”

Zachary Abuza, professor, National War College, Washington, D.C.

From Giang’s point of view, a law limiting who can share news would be difficult to enforce and to follow. If this regulation comes into play it would likely create a situation where everyone is technically breaking the law – heightening the atmosphere of fear online.

“When you make the regulations very hard for both users and providers to follow it could mean that everyone will break the law. This means that there’s always a possibility for you to be punished,” Giang said. “[Users] would self censor themselves because of that.”

Since the September Reuters exclusive on heightening internet rules, Vietnam’s information minister Nguyen Manh Hung announced new regulations for dealing with “false” content online. On 4 November, the minister stated such content must be taken down within 24 hours.

According to a spokesperson at Amnesty International’s regional office, the government is potentially “suffocating” one of the few places left for the discussion of politics, the economy and social issues in Vietnam by its strict policing of sites including Facebook and Google.

“Vietnamese authorities have shown they are willing to abuse power to surveil and harass dissidents, and Decree 53 adds to their toolbox,” the spokesperson stated.

“The international community needs to show solidarity with the Vietnamese people and keep scrutinising the way Vietnam controls its society, especially online.”

The Amnesty spokesperson further highlighted the impact the country’s harsh cybersecurity laws could have on the deterioration of human rights in the region.

“Other countries in ASEAN are watching Vietnam and replicating their tactics,” the spokesperson said. “Without continued pressure from the international community, this trend will continue and worsen.”

Party position

The unusually long interim period between the 2018 cybersecurity law and the release of a guiding decree showcases the push and pull between conservative and reformist factions within the government. While reformists worry over the impact requiring data localisation could have on economic growth, conservatives feel that control of the online ecosystem is paramount for maintaining national security.

“[It is] national security in the sense that it is more about ideological control of the internet,” said Giang. “I think [the decree] reflects a wider trend of a more conservative turn in Vietnamese politics in the last four years.”

Abuza shares this view.

“The crackdown on dissent has not let up – it’s gotten worse.”

The government is particularly focused on Facebook due to its popularity in the country. There are approximately 70 million Facebook users in Vietnam. Yet years of debate have led up to issuing Decree 53.

Meta, Facebook’s parent company, declined a request for comment.

International tech firms have generally caved to Hanoi’s demands to take down content. In the first quarter of 2022, Facebook complied with 90% of take-down requests, Google with 93% and TikTok with 73%, according to Vietnam’s Ministry of Communication.

Despite this high level of compliance, the government is seeking further methods to monitor social media sites.

“They’re very compliant, it’s just the government doesn’t trust them to always be compliant and always to be so quick,” Abuza said. “There are going to be greater consequences should you not comply with our demands.”

Data storage

Although the 2018 Law on Cybersecurity now has a guiding decree to make data localisation enforceable, it is still unclear how data will be stored both from a legal and technical perspective.

“There are some ambiguities and some sort of conflicts,” said Kent Wong at Ho Chi Minh City-based VCI Legal. “All the big tech guys are concerned about how it’s going to be implemented.”

As Wong explained, there is confusion if data can only be stored in Vietnam, or if it’s sufficient to store a copy onshore. Further, it’s uncertain what form the data will be stored in.

“These are technical things but it makes it unclear for the big tech companies how to comply,” Wong said.

And while large firms will be able to shoulder the costs of setting up a local office and storing data in Vietnam, smaller companies may not have the capital. “For the smaller startups, they might not be able to invest that much in order [to comply] so that may be a deterrent to the long term,” Wong added.

A data security expert from Vietnam also has concerns about how smaller telecommunication operators will store data in relation to Decree 53. The expert asked for his name to be withheld as he and his employers may face scrutiny from the Vietnamese government for speaking out.

For the expert, there is nothing which makes it clear in Decree 53 that tech firms cannot simply store a copy of user data in Vietnam. If only the copy is stored in the country with an encrypted key kept outside of Vietnam, user data will be relatively secure. While he expects big players in the tech industry to utilise this loophole, less experienced companies may not.

“[Smaller companies] don’t really have any person like me to show them how to do this correctly… It’s more than likely that they would do it wrong,” the data expert stated.

He pointed out that while government officials voted for the 2018 cybersecurity law without revealing their identities, the law restricts Vietnamese people’s online anonymity.

“It was kind of ironic because when the National Assembly representatives voted for the law they voted anonymously and they did it to take away the right to stay anonymous on the internet,” he noted. “They did not expose who voted yes or no.”

From Wong’s perspective, the data localisation order can be seen as a savvy move to rake in taxes.

“Now that there’s a nexus, something closer, and they have a physical server or a cloud which is held in this territory, then they can tax any revenue later on. So this is a bit of a smart play by the Vietnamese government,” Wong said.

Abuza also gestured to potential monetary benefits. The country’s first domestically-owned data centre officially opened on 15 August in Ho Chi Minh City. According to Abuza, prominent political figures are investors in the Tan Thuan CMC Data Center.

“What a coincidence, they’re demanding data localisation… I don’t believe in coincidences.”

The anonymous data security expert questions government claims the cybersecurity law is for citizens’ protection.

“They keep saying that the cybersecurity law protects the privacy of Vietnamese,” he said, questioning the purpose of the law. “What the hell… it doesn’t.”

For him, potential government access to user data poses a very real danger.

“As a Vietnamese I’m more worried about my government than Google or Facebook. Of course I don’t like big tech to snoop on my data, but I don’t think Google or Facebook can harm me compared to the government.”