The art of war

Despite recording many iconic scenes from Vietnam's decades-long struggle for independence through his art, the story of Colonel Pham Thanh Tam has largely gone untold. But the man behind the pencil will not go forgotten.

By James Springer

Vietnam: The Art of War is a project that builds on more than 20 years of research and documents the decades of conflict that took place in Vietnam during the 20th century through the experiences of the Vietnamese artists who lived through it. All images and videos courtesy of Witness Collection.

For much of the world’s population, some historical names are inextricably linked to war in Vietnam. Christian de Castries lost French Indochina after losing the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ. Richard Nixon was branded a monster over his indiscriminate bombing campaign. Photojournalist Sean Flynn became a man of mystery after disappearing in Cambodia. Michael Herr became a best-selling author with his book Dispatches.

In most cases, the fame was justified. Tim Page, for example, didn’t become the world’s leading war photographer at the time by relying on fabricated press briefings and drinking the kool-aid at five o’clock follies. He went out to locations in Vietnam that most Marines wouldn’t dare go, snapped pictures that fed into Life and Time magazines, and survived an IED blast that robbed him of 20% of his brain.

However, due to the cruel nature of Western-orientated history, it is safe to say the world will not remember, or even know of, Colonel Phạm Thanh Tâm, who sadly passed away on 30 May 2019. Which is a shame, because Colonel Tâm – journalist and war artist – made Richard Nixon look like a cheerleader, Sean Flynn a tourist, Michael Herr a by-stander and Tim Page a dilettante.

On meeting Phạm Thanh Tâm in April 2018, despite physical signs of his growing years, he flicked through piles of war sketches with a mental alacrity that belied his age. He remembered the time, place and situation of each piece in astounding detail. Although, given the history he retold through his sketches, maybe it was not that surprising – the memories he conjured so easily would be difficult for anyone to forget. “Even in wartime,” recalled Tâm, “colours were very intense… We always remembered and we always recorded.”

After being born close to Hải Phòng, a port city 120km east of Hanoi, in May 1932, Tâm and his family fled the city when he was only 14 years old under occupation from French colonial forces. In their new community run by the Việt Minh, an organisation leading the struggle for Vietnamese independence from French rule, Tâm began acting as liaison between Military Zone 3 and other areas, carrying letters to and from resistance camps.

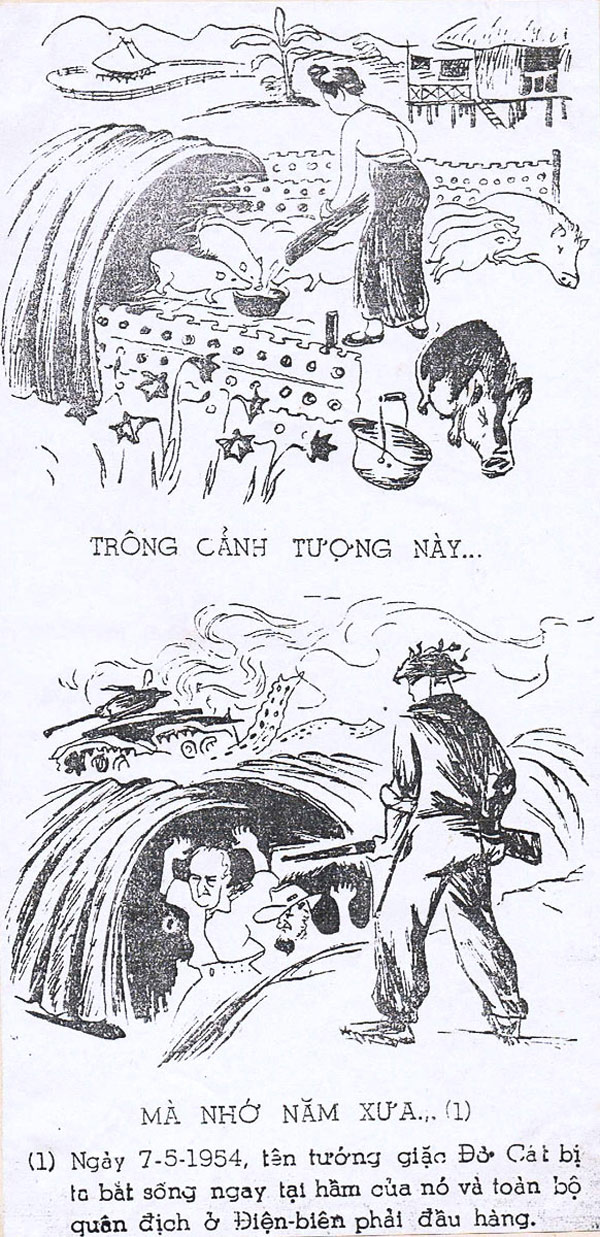

A few years later, and after attending a six-month painting training course, he and other course mates were tasked with carrying out an early version of psychological warfare in aid of the resistance to French occupation. Tâm produced wall posters and subterfuge propaganda leaflets and distributed them to intimidate French units stationed nearby. “One slogan was very strong,” Tâm recalled. “‘Drinking alcohol means drinking the blood of our people.’ It was true because… if you used rice to make alcohol, then there would not be enough rice for people to eat.”

Although still young, if he were caught, Tâm risked execution by firing squad. However, as Tâm pointed out in Sherry Buchanan-Spurgin’s Mekong Diaries: Drawings and Diaries from the American-Vietnam War 1964-1975, “I was too young to know what death really meant.”

Tâm officially joined the Việt Minh in 1950. “So I signed; I was not concerned,” Tâm said, in reaction to committing at least three years to military life. In his first assignment with Infantry Regiment 34, he worked for the Tất Thắng newspaper, helping the population of Nam Định to raise their own militia army to fight French forces. He then transferred to Artillery Division 351 to work for Quyết Thắng newspaper as a journalist and artist, travelling to China for artillery training in 1952. “At the time, we only had two cannons,” Tâm said. “After that, the Soviet Union and China supplied us with an entire artillery regiment.”

On his return to Vietnam in late-1953, Tâm and his division walked 300 kilometres from Vietnam’s northern border with China to the small town of Điện Biên Phủ.

At this point in his life, the First Indochina War had reached its crescendo and was about to burn itself out like a violent tornado. The Việt Minh had suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties. More than one hundred thousand French Far East Expeditionary Corps troops had been declared killed or missing. Hundreds of thousands of civilians had been killed in the process.

The convergence of the two sides at Điện Biên Phủ was to be the final straw; to the victor would go the spoils; a continued colonial empire in Southeast Asia or a country returned to its people.

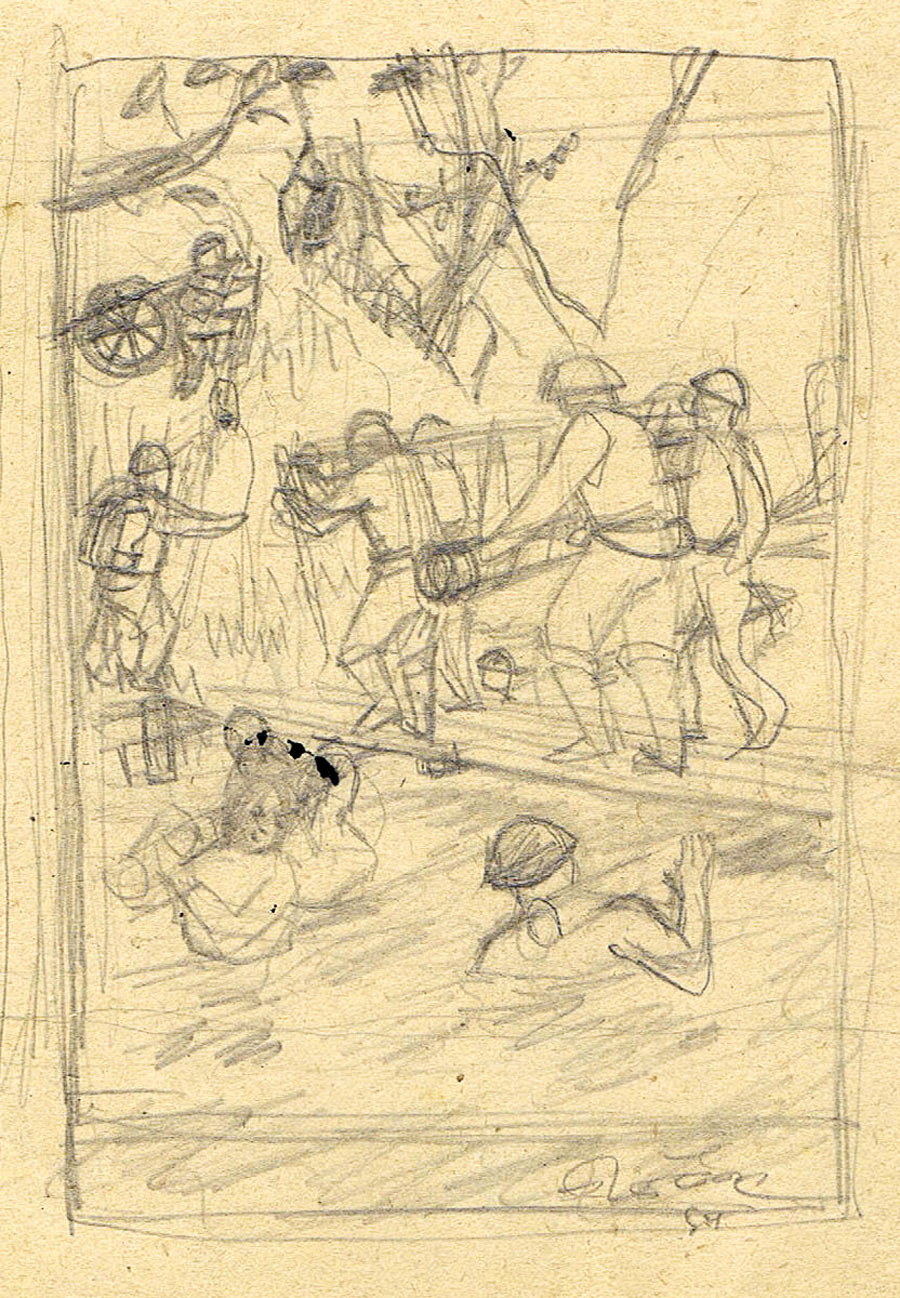

Tâm recorded his journey to Điện Biên Phủ, and the ensuing battle, through journal entries and hasty sketches, finally making his story known to the outside world in English and French by publishing Drawing Under Fire: War Diary of a Young Vietnamese Artist in 2005.

Between documentary evidence of his division carrying their artillery equipment on the long march to Điện Biên Phủ and General Võ Nguyên Giáp’s revolutionary tactic to use them as mobile units, Tâm’s account was filled with compassion, amazement and a growing sense of pride in his people’s sense of purpose and determination.

“The marching was arduous,” Tâm said. “It must be said,” he continued, “that for us to march like that, the sappers had to build the road beforehand… There were also young volunteers.”

His division, and others like it, did not go unnoticed by Hồ Chí Minh, who referred to the Việt Minh as “soldiers of bronze foot and iron skin”.

When Tâm recounted his experience of the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ, he did so with a pragmatism that could only come from having lived through such a hideous moment in time. His description of blown out bunkers covered in the flesh of comrades were not told to shock but only to define. His explanation of how a Việt Minh soldier wedged himself below the undercarriage of a firing artillery cannon to prevent it from rolling down a hill, being gradually crushed to death in the process, was not told for effect but with pride.

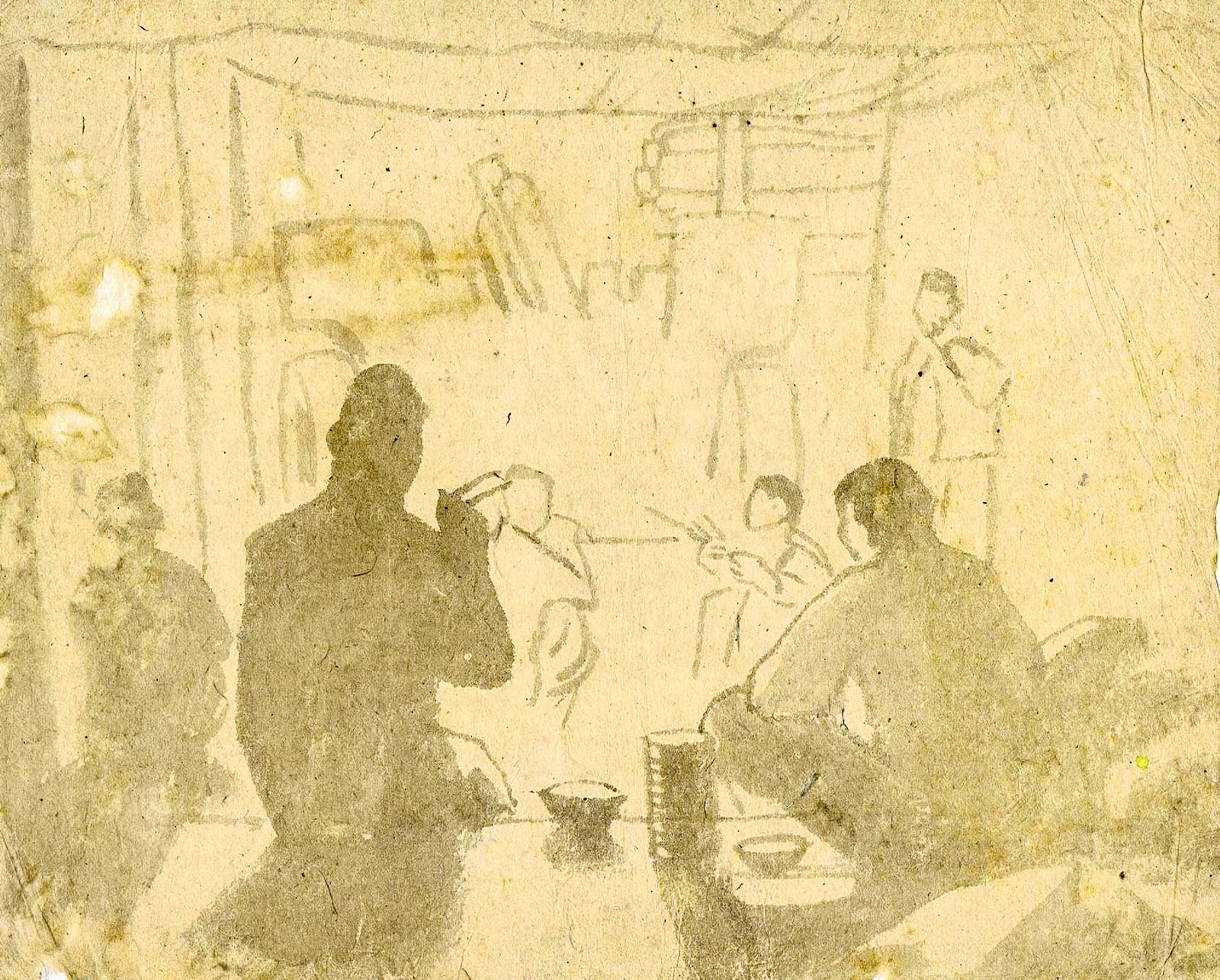

However, Tâm also included memories of beauty and joy. As he described how the Việt Minh ate, how they were entertained by dancing troupes, and how, on the evening after victory, the lone wail of a harmonica played out over the destruction that Điện Biên Phủ had become, it was easy to see how such memories could be dominated by the good over the bad.

Not least of all as he, and all Vietnamese at Điện Biên Phủ, imagined they had finally reclaimed their country from colonial rule after the guns stopped pounding. “My artillery unit took part in Điện Biên Phủ campaign for 56 days and nights, from the beginning to the end,” Tâm said. “On 7th May 1954, we beat the French and claimed victory.”

Hồ Chí Minh’s dream of a unified Vietnam, however, did not come to pass. And, although Tâm revisited the north-western region of Vietnam to document how ethnic communities were starting to rebuild, the Geneva Accords ensured that Vietnam would not become united. Instead, Tâm found himself left with half a country – not even half, by mathematical standards.

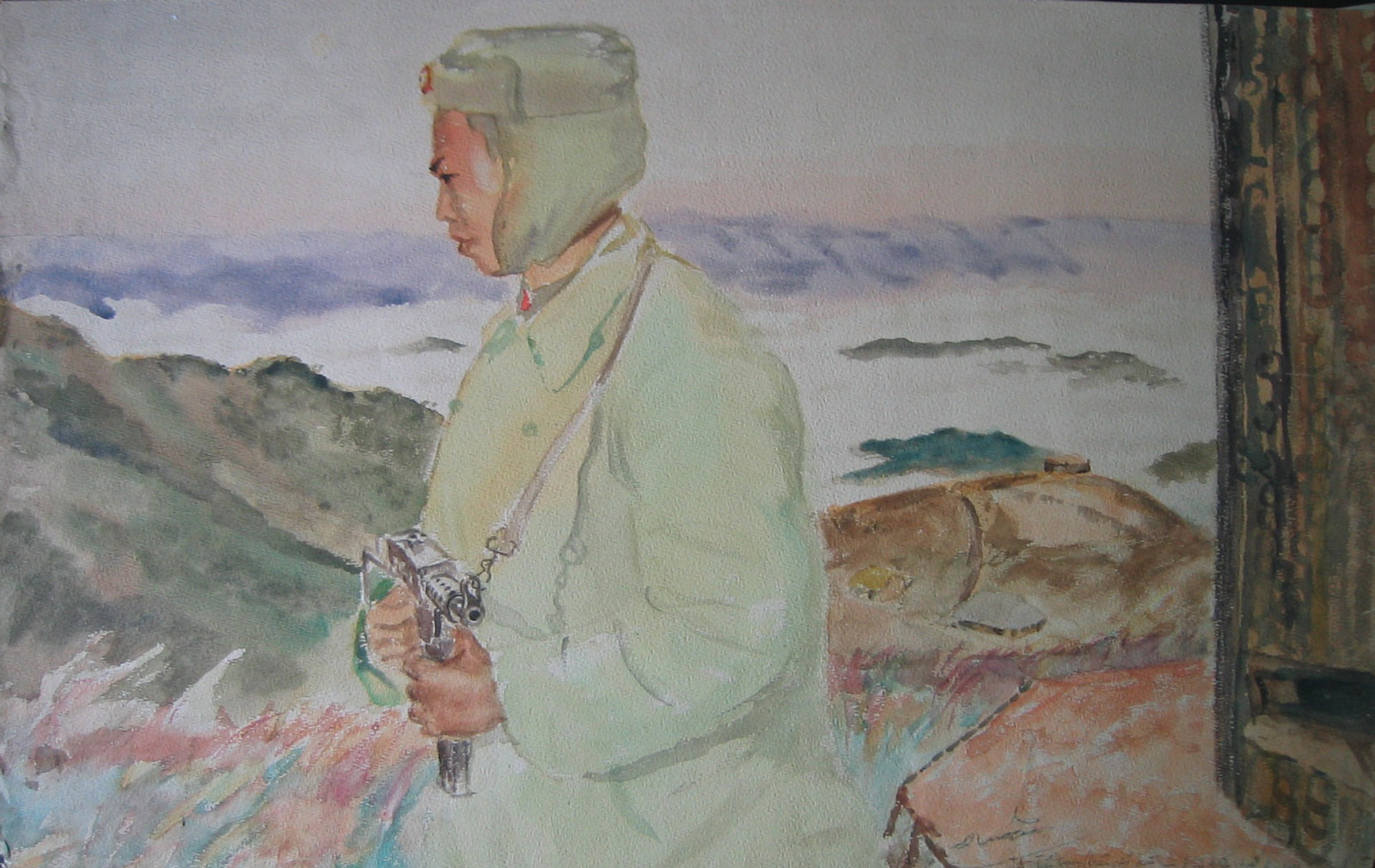

No wonder then, as the Second Indochina War (or the Vietnam War) started, Tâm volunteered for the front in South Vietnam while enrolled in the Vietnam Fine Arts College. He was given permission to paint from the battlefields in Khe Sanh and Quảng Trị, the shelters and caves along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and the mountainous regions in northern Vietnam.

With his experience of Điện Biên Phủ, Tâm’s cartoons of American soldiers hunkered down at Khe Sanh Combat Base are easily relatable. “At that time, the press in the world considered Route 9-Khe Sanh as “a Điện Biên Phủ” in the battle against the US,” Tâm recalled. “Every now and then the enemy’s aircraft came and dropped bombs. It didn’t matter if they hit the target or not… the only way was to run through the area without being hit by the bombs. If we could do it then we were lucky; we escaped death.”

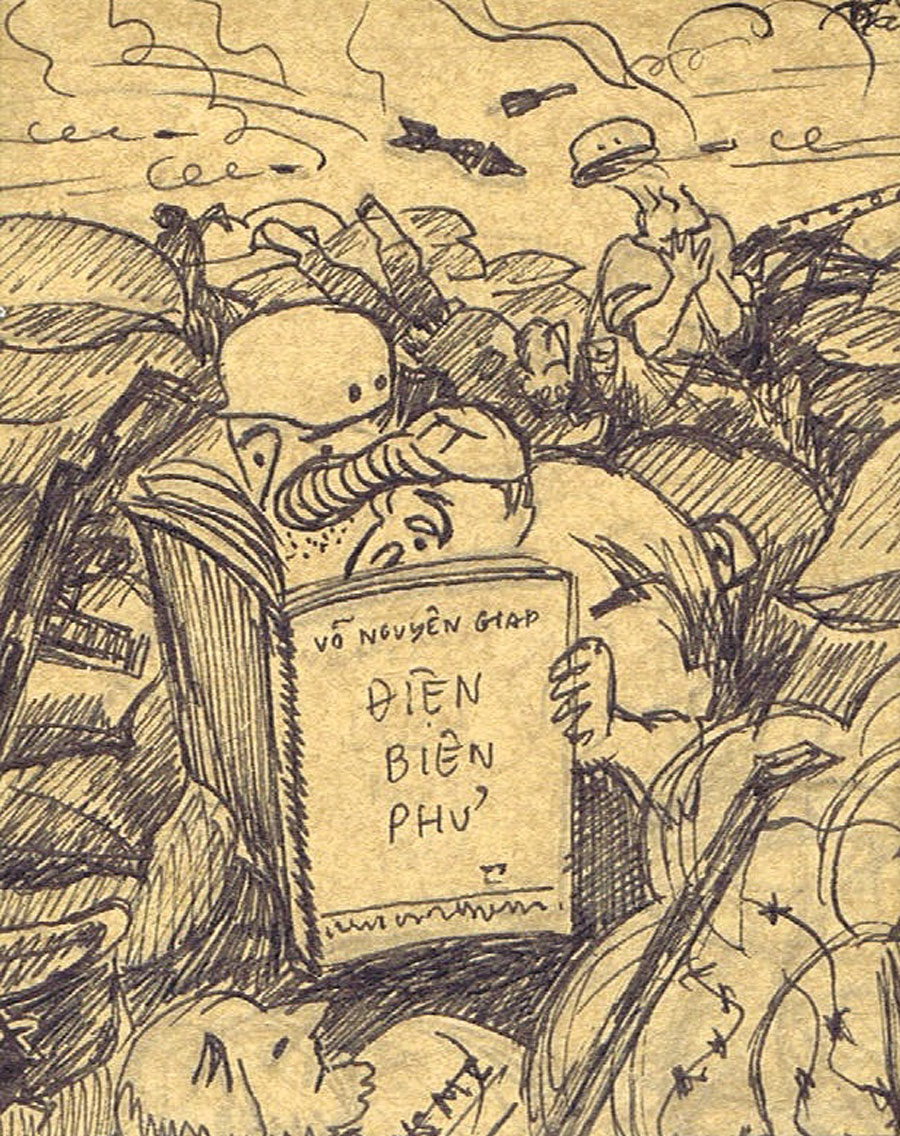

In one of his cartoons, clearly confused while reading from the handbook “written” by Võ Nguyên Giáp almost a decade before, American soldiers are portrayed as utterly dumbfounded how to fight back. Arguably, Tâm had a clearer insight to the US military’s situation than the American public had at the time – even possibly most of its leaders. “My caricatures were also inspired by things that I found humorous and deserved to be satirized.”

After he graduated the Vietnam Fine Arts College in 1967, Tâm was tasked by the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) with opening art classes in North and South Vietnam. “When I was in Hanoi during the anti-American period, everybody had evacuated from the city,” Tâm said. “People lent me their house as I could help them look after them. But there were times when I got to stay in a place that was not a house. For example, once, before participating in The Route 9-Khe Sanh Campaign, I stayed at Chu Văn An high school. I borrowed that room to stay. I brought my belongings, my paintings and old sketches with me and lived in a room.”

As part of a Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) government directive to spread art and propaganda among Việt Cộng forces, it was an important job.

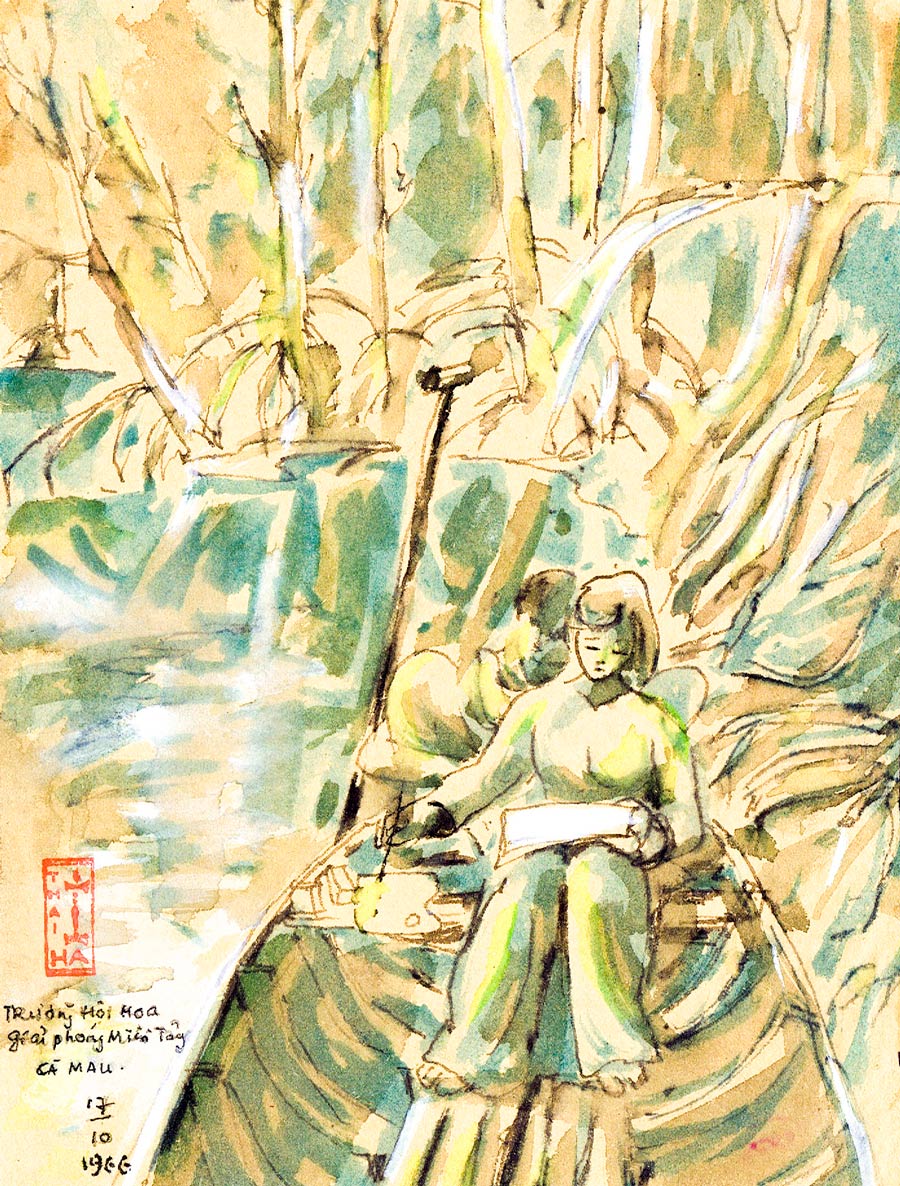

In this capacity, Tâm was based in Hanoi but organised for paintings created in South Vietnam to be delivered to North Vietnam, and vice versa. These artworks were then exhibited in the grand colonial buildings of Hanoi, in ethnic minority villages in the jungle forests of the Central Highlands, and in mobile resistance camps set up in the Mekong Delta’s mangrove swamps. Tâm’s role aided other artists like Thái Hà, who was already stationed in South Vietnam with the National Liberation Front (NLF) opening similar art classes.

Although based in Hanoi, Tâm made frequent trips along the Ho Chi Minh Trail and Highway 1 to Quảng Trị Province. “When đi B (travelling south), we preferred to go long B than short B,” Tâm said. “Going to that battlefield was considered “short B”, which means “B5”. On B5 we had to confront the enemy and often get hit by bombs from B52 bombers. The artillery shelling there was more fierce than other places. If we could go further to the South, it was less dangerous.”

Between 1968 and 1975, Quảng Trị City was considered an important symbol of South Vietnam’s government authority. As Quảng Trị’s northern border formed part of the 17th Parallel, it was a highly contested area with near constant conflict between PAVN and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces. In January 1968, Quảng Trị City served as one of the many locations under attack as part of the PAVN’s Tết Offensive campaign. In June 1972, the Second Battle of Quảng Trị took part in response to the Easter Offensive earlier in the year, again plunging the city and province into turmoil.

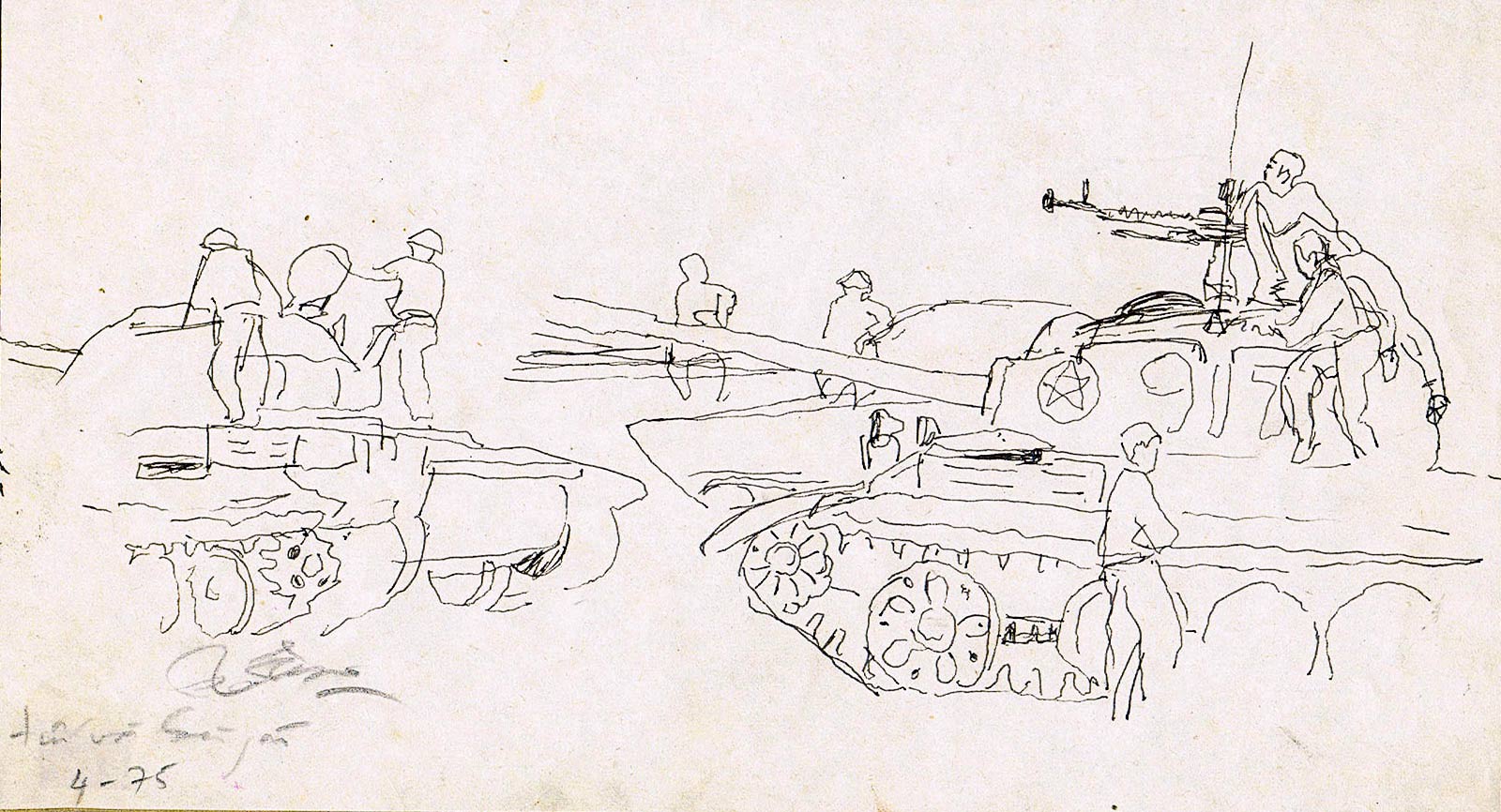

Then, twenty-one years after victory at Điện Biên Phủ, Tâm joined elements of the PAVN, the NLF and Việt Cộng militia on the final march to Saigon in April 1975. As American personnel coordinated their last-ditch evacuation, Tâm and his compatriots rolled into Saigon’s northern suburbs with tanks and armoured vehicles, encountering little resistance on what would be the last military action of the Second Indochina War.

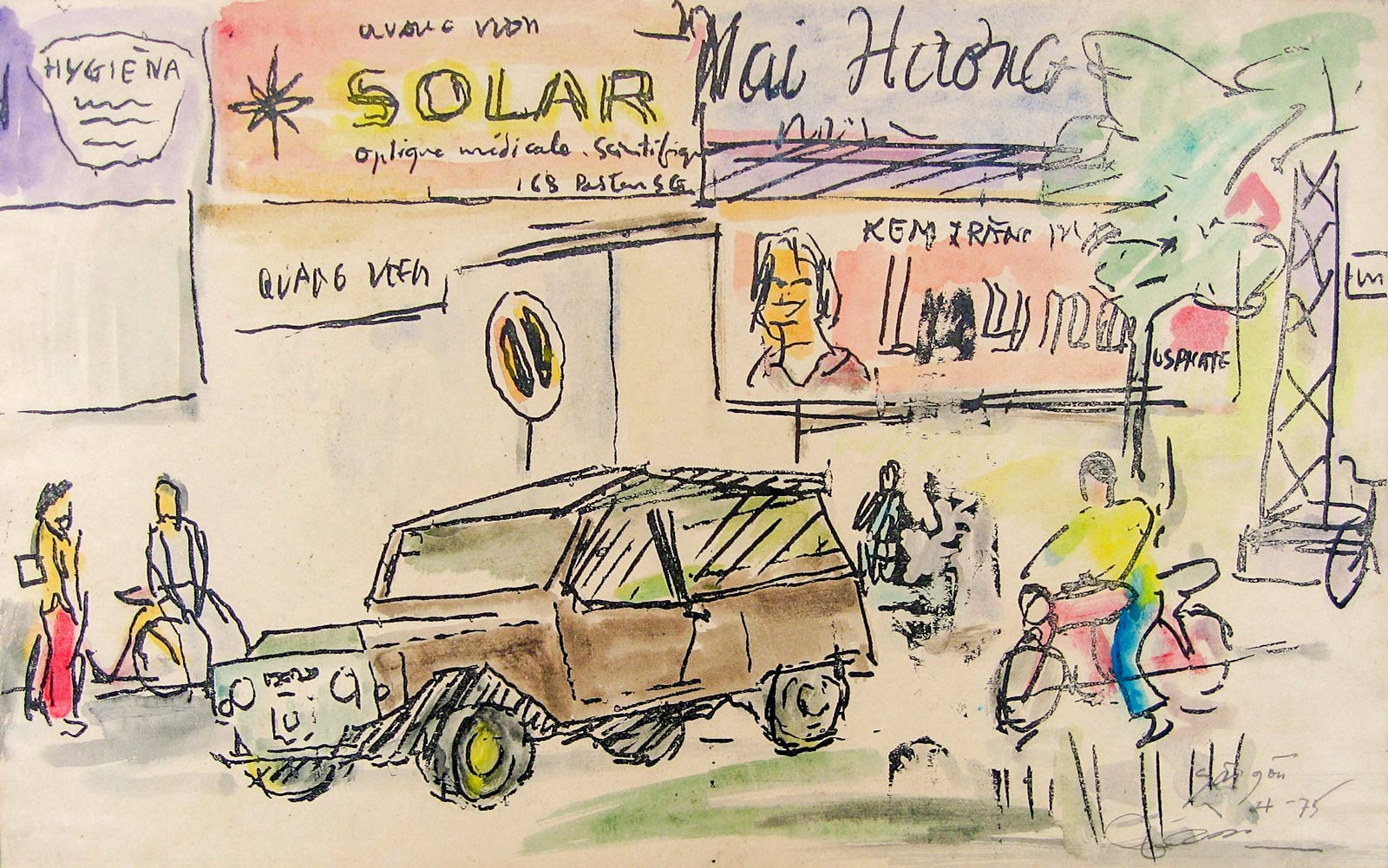

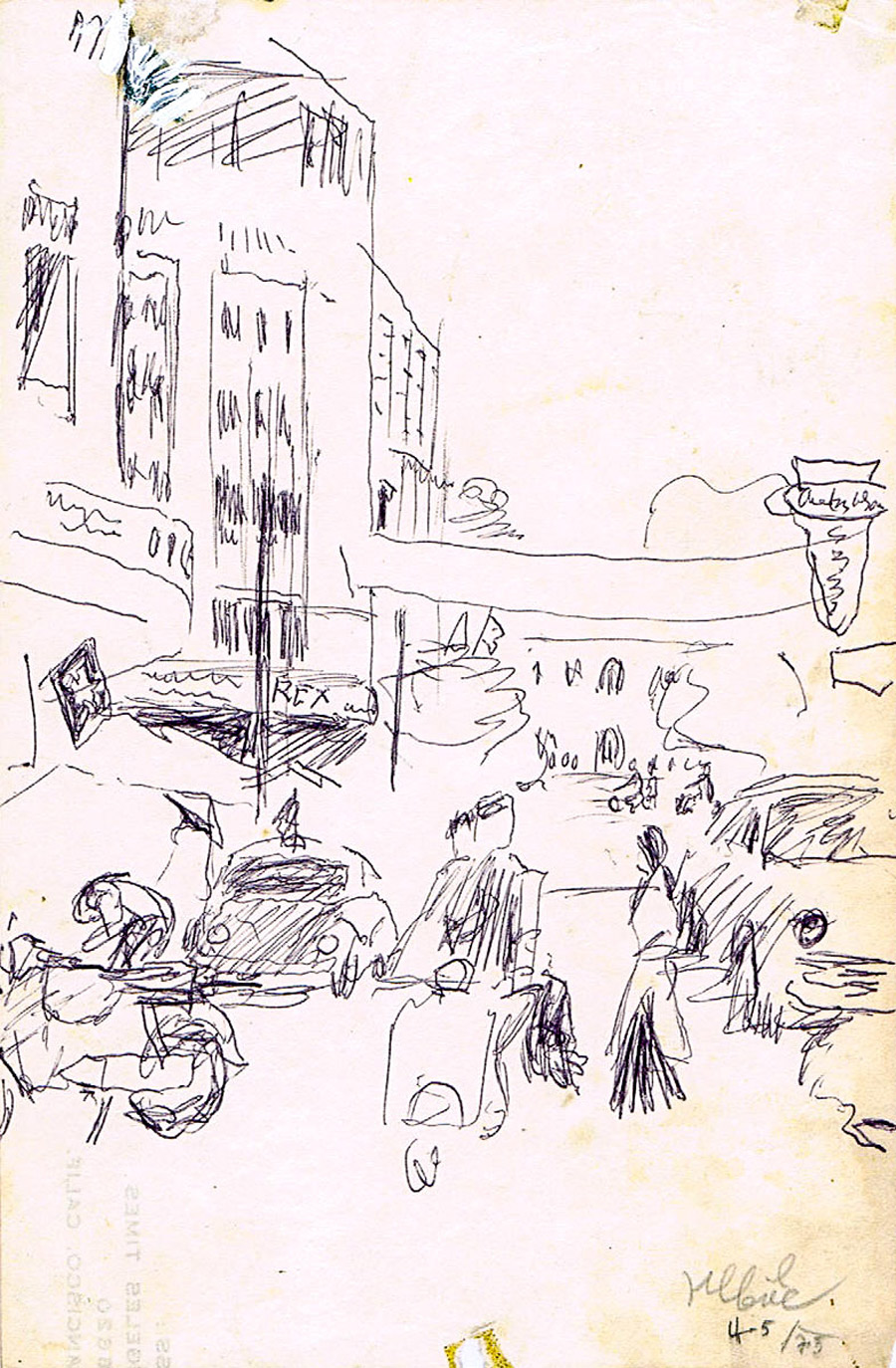

Once in Saigon, Tâm depicted scenes of surprising normality on the day of liberation, 30 April 1975. In stark contrast to what he was used to in Hanoi, Tâm revelled in the bustling streets, foreign brands, nightclubs, modern dress, cars and motorbikes that he had never seen before. He took the opportunity to sketch the Rex Hotel, in the same way that other artists like Nguyễn Đức Thọ were equally fascinated by Saigon’s architecture.

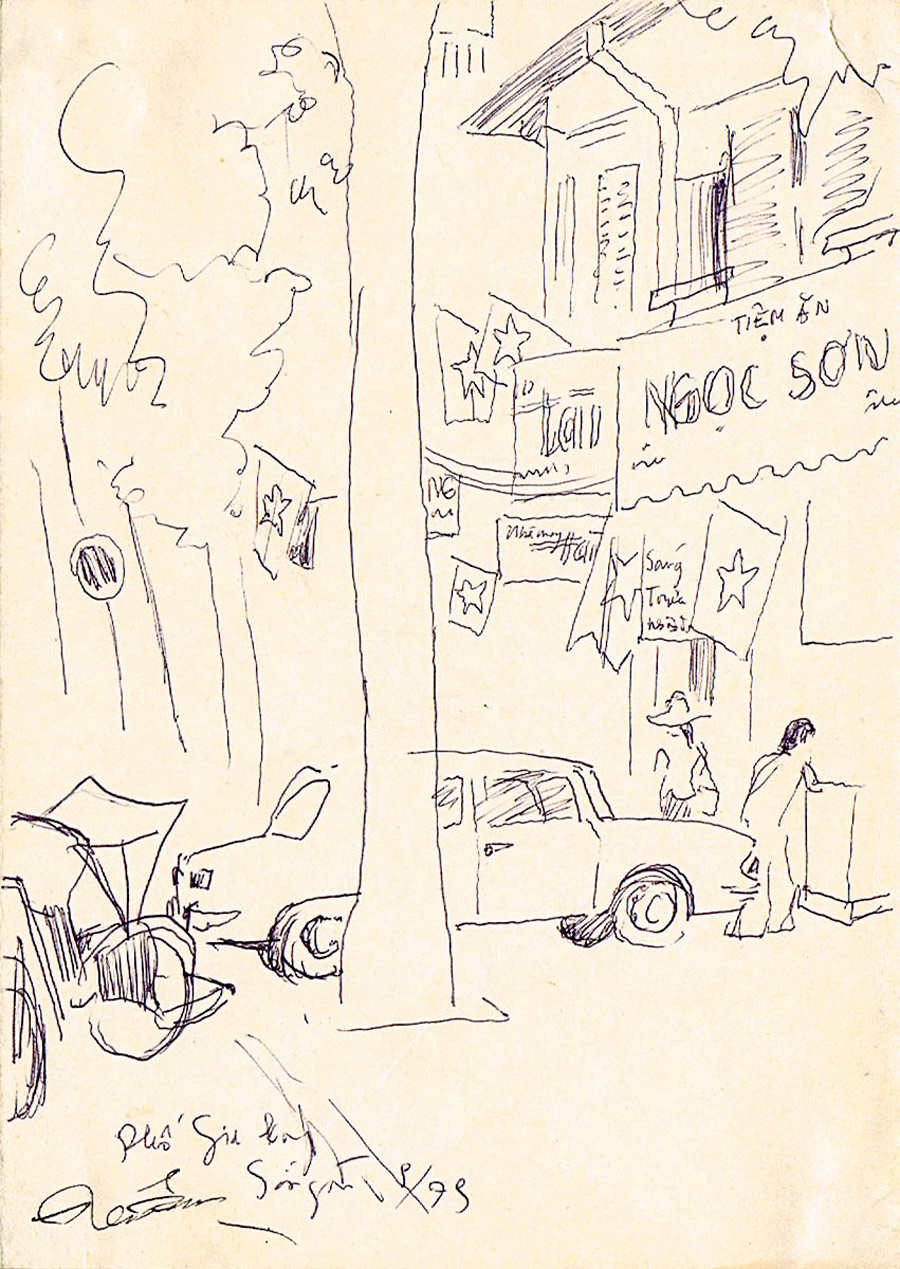

As much as Tâm was taken with the unfamiliar, he did not miss the opportunity to record the recognisable in Saigon. Quick sketches of drinks stalls on the street-side would have resembled a slice of home for him. “The city was still full of the liberated atmosphere. Then I witnessed the evenings when the lam-carts carried fruits and rice to give to the soldiers and visitors in front of the Independence Palace.”

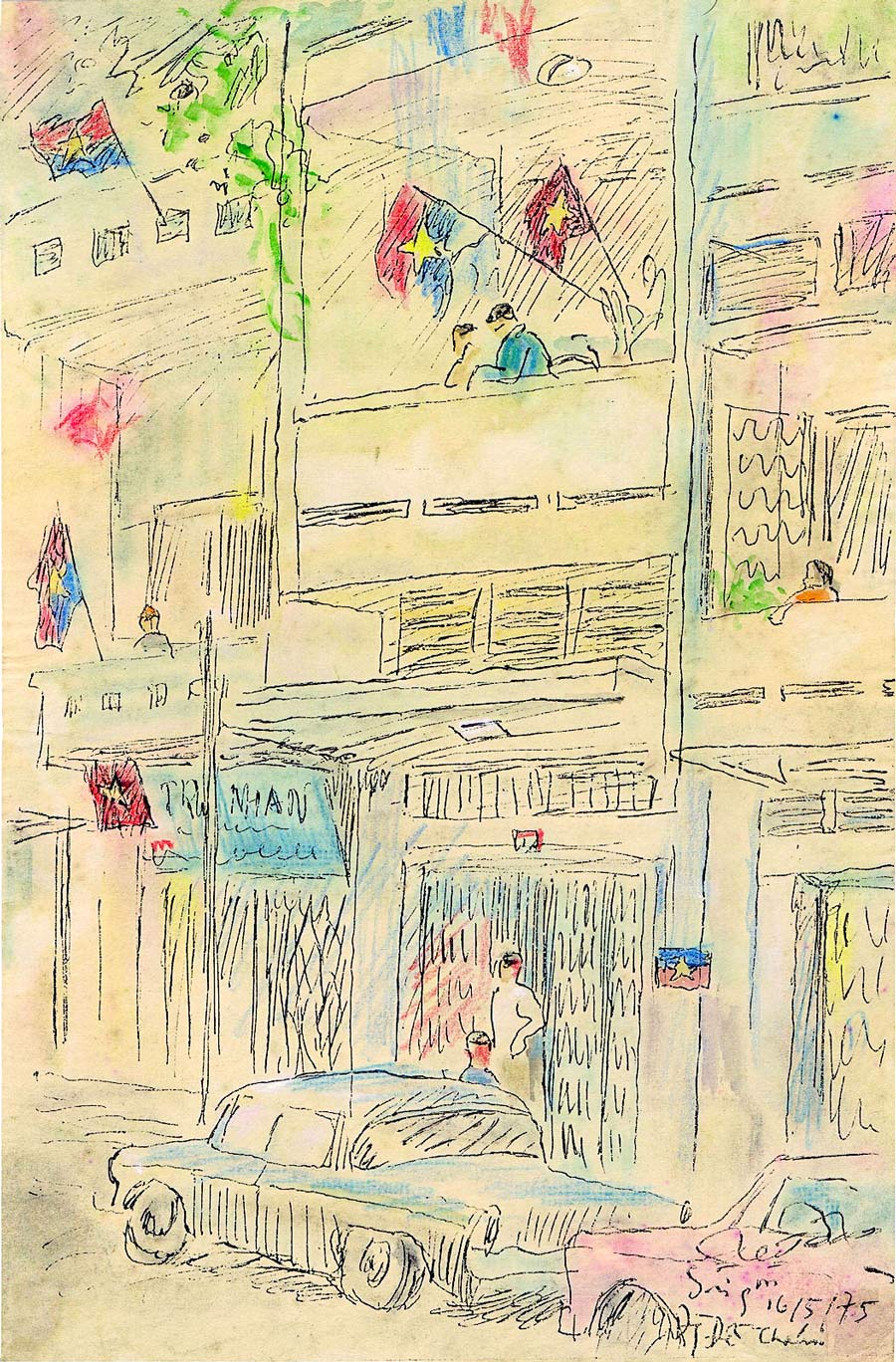

Terraced shop lots pinned with DRV and NLF flags would have solidified his sense of belonging in the rival capital city. An unassuming building on Gia Long street (now Lê Thánh Tôn street) would not have escaped Tâm’s attention as a neighbour to the rooftop used as an assembly point for some of the last prominent US-RVN personnel to leave Saigon via Huey helicopter.

Particularly after the initiation of đổi mới free-market economic reforms in 1986, Ho Chi Minh City, renamed after its fall in 1975, held an allure for many artists from North Vietnam. The sense of artistic and social freedom allowed them to explore aspects of an artist’s career hardly encouraged in the North. In some cases, even the warmer weather offered a boon.

Tâm moved to Ho Chi Minh City with his family after he retired from the PAVN in 1989. As a colonel, Tâm was given a house, which he lived in for the rest of his life. From there, Tâm devoted his time to creating images of his experiences during the resistance wars from his frontline sketches, using signature materials; oils, silk, watercolour, pencil and pen.

As is often the case, people remembered through the prism of war can be misunderstood. Although branded a monster, Nixon inherited the war in Vietnam rather than having started it. Sean Flynn and Tim Page sympathised with North Vietnam’s cause to unify the country and worked as much to reveal the absurdity of the US government’s involvement than to document it. And although his reputation from Dispatches earned him a successful career as a screenplay writer, Michael Herr never truly overcame his experience of the Vietnam War, carrying the ghosts of the dead with him for his remaining years.

In the same way, Colonel Tâm was not merely a “communist enemy”. In reality, he was a patriot, a father, a husband, a compatriot and an undeniably important documentarian. In the pursuit of objectivity, Tâm’s contribution to Vietnamese history should be appreciated and remembered for the dedication and bravery it entailed. The world has lost a fascinating historical figure. “I was lucky to be able to witness both major victories against the French and the Americans,” Tâm said. “That’s what I find fortunate about my life.” Luckily, his stories will live on.

Read more fascinating stories of Vietnamese war artists at Vietnam: The Art of War. For more video interviews with war artists, visit Witness Collection’s YouTube page.