It is a relatively recent history in which motorbikes have become synonymous with everyday living in Vietnam, and even more recently that helmet-wearing has become the norm.

With more than 60 million motorbikes in Vietnam today, the fourth largest total globally, safety issues related to their usage have been of top concern for decades. Since the early 2000s, a particular focus has been put on the helmet to quell the most egregious impact of the dawn of the motorcycle: Traffic fatalities.

In the area of public health, Vietnam’s helmet laws have been both incredibly successful, while, paradoxically, simultaneously ineffectual. Helmet-wearing has gone from nearly nonexistent to as high as 90%. But, despite this huge endeavour, most helmets remain insufficient in the event of a crash and road accidents persist as the leading cause of death for people aged 15-29.

Although the insufficiency of the majority of helmets has long been common knowledge, solid data to support this fact has been missing – until recently.

In October, the road-safety nonprofit AIP Foundation published their study in which researchers randomly selected 540 drivers and passengers in Saigon and Thai Nguyen city, swapping their current helmet for a high-quality one. The surrendered helmets were then subjected to a range of physical tests to see if they met national standards. As AIP’s study found, “an astounding 90%” of the collected helmets did not pass these tests.

The results highlight that, while getting helmets on heads has been a successful and important effort, much work remains to make helmets an effective tool to decrease brain injuries and traffic fatalities in Vietnam.

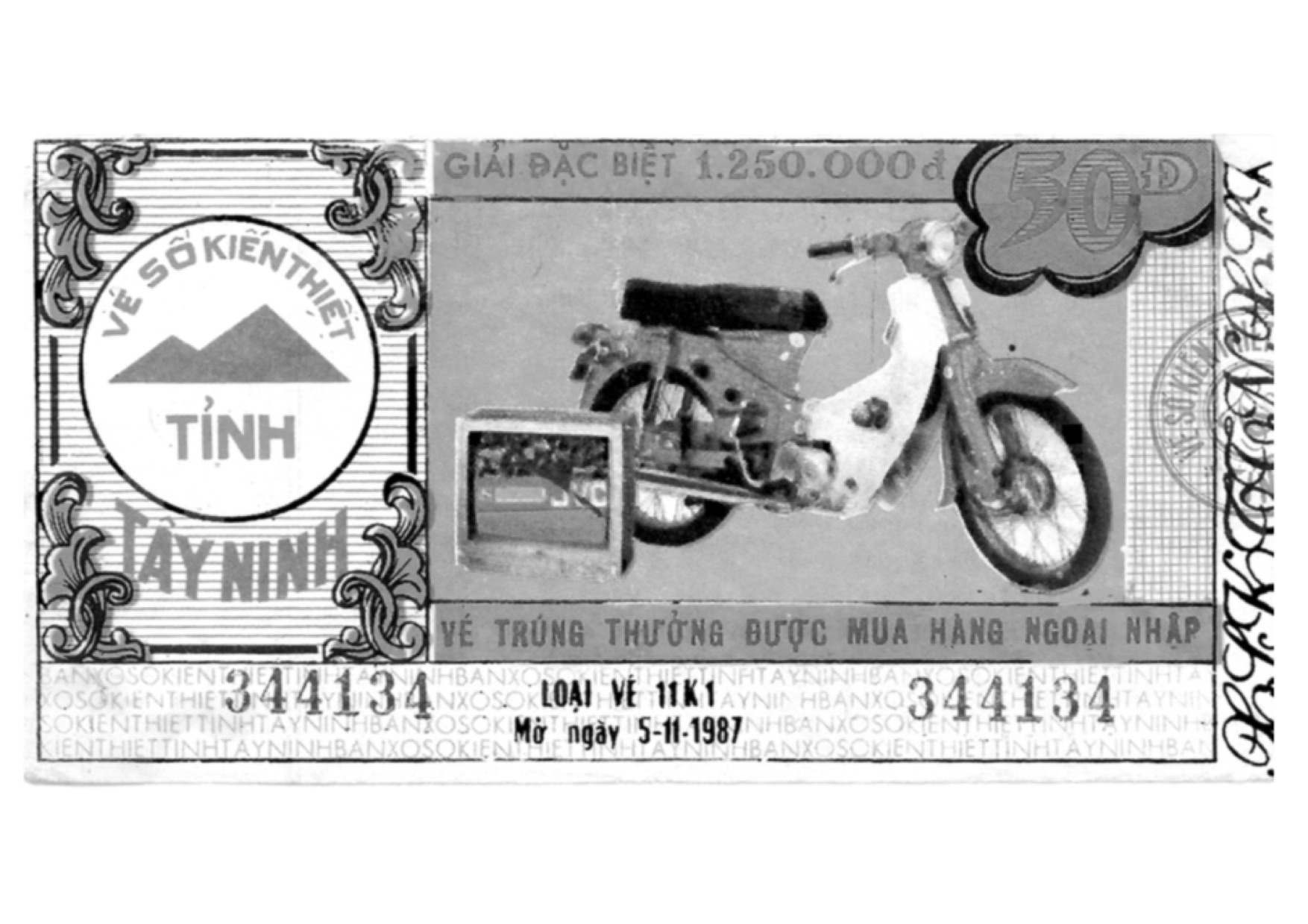

The blossoming of motorbike culture in Vietnam began in 1986 when the government initiated the Doi Moi reforms liberalising the economy. The broad policy ushered in foreign imports such as the motorbike, which quickly became a signifier of upward social mobility. Between 1990–2010, the number of motorbikes on the road increased 30-fold and, by 2011, there was more than one motorbike per household nationwide in Vietnam.

Dr. Pham Viet Cuong, the head of the department on public health informatics at the Hanoi University of Public Health, has been researching road safety in Vietnam for a quarter of a century. He was also the principal investigator for AIP’s recent study.

Sitting at a cafe with a view of the passing traffic on Saigon’s busy Cao Thang Street, Cuong recalled his initial 1996 foray into studying road safety, a small-scale study enabled by a meagre grant from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that compared mortality rates related to traffic injuries with other health risks.

Looking at the results, it became aparent that nonspecific injuries were causing 30-40% of the deaths among the Vietnamese youth population.

“We thought okay, we have to find out more,” Cuong remembered.

Drawing from his studies, Cuong explained that while the Doi Moi economic reforms precipitated major economic growth, and ultimately significant progress in Vietnam’s public health, they also correlated with a dramatic increase in casualties on the roads.

“Children were not dying young because of polio or diarrhoea, but they were dying because of drowning and road safety,” Cuong said.

This is a trend that continues on, with approximately 2,000 young people dying every year in Vietnam due to traffic accidents. A leading cause of these fatalities is that young people often do not wear helmets while on motorbikes, despite those aged six and above being mandated to do so under the 2007 law.

A study of traffic incidents involving children in Ho Chi Minh City, with data collected from 2010–2015, showed that 74.9% of child deaths were among highschoolers. The study found that 85% of the children in accidents were male and over 80% occurred while a child was driving.

Vietnam’s first helmet law, which passed in 2001, required motorcycle drivers to wear helmets on specific roadways. With limited enforcement of this legislation, the use of helmets was estimated at 30%. In June 2007, the government passed a decree that made it mandatory for all motorcycle drivers to wear a helmet on all roads from December of that year. With the law in place, helmet-wearing reached 90%.

The quick adoption of helmets was a surprising cultural shift says Ivan Small, an associate professor at Central Connecticut State University who studies mobility in Vietnam.

“Before the law passed, people said that it was never going to work, people are not going to change their lifestyles,” he told the Globe. “When people started talking about helmets in the early 2000s, no one wanted to wear them. People used to say that a helmet was like a rice cooker.”

When helmet-wearing reached 90%, everyone thought that it would help to reduce the number of brain injuries and deaths. But we didn’t see that happening

With the 2007 helmet law in place, the demand for helmets increased dramatically. This demand drove the burgeoning market for cheap, unstandardised helmets which are readily accessible from roadside businesses. But despite this successful push to get people wearing helmets en masse, riding a motorbike remains unsafe in Vietnam due to the prevalence of insufficient cap helmets and counterfeit helmets, says Cuong.

“When helmet-wearing reached 90%, we thought it was a great success and everyone thought that it would help to reduce the number of brain injuries and deaths initially. But after a couple of years, we didn’t see that happening,” he said. “We did a lot of studies and looked at a lot of issues and we saw the problem of unstandardised or low-quality helmets.”

Government stipulations for the production of helmets have been implemented – in November 2009, the Ministry of Science and Technology stipulated all helmets for sale must have a Conformity to Regulation stamp of approval – but the proliferation of shoddy helmets remains.

Drivers who do not conform to these regulations can be fined up to VND200,000, or about $9. Regardless, a lack of implementation of this directive on helmet quality and the self-regulation of the standardisation process leaves many drivers wearing inadequate helmets. This is something Cuong feels strongly about, gesturing out the window as individuals wearing cap helmets drive by.

“If you look at those people there you can see that many of them are wearing them now.”

Beyond blatantly unsafe helmets, the matter becomes complicated by how and how long you wear your helmet too.

“Lots of people use their helmets for six or seven years,” Cuong stated. This, along with factors like sweat, rain, and the extremely hot weather are likely to impact the safety that a user’s helmet provides.

With the number of motorcycles only rising in Vietnam, Cuong pointed to the importance of AIP’s recent study, as well as the enormous challenge ahead to lower road fatalities – a scourge among the country’s youth.

“To change the policy to improve this [road deaths] is not easy because now everyone uses motorcycles. We have a population of 96 million and 60 million motorcycles,” he said. “Very few places in the world do they have the amount of motorcycles like in Vietnam. It’s very convenient, it’s cheap to buy, it’s cheap to operate, but it’s dangerous, very dangerous.”