Preventing a pandemic of black-market vaccines in Southeast Asia

With the Covid-19 vaccine on the brink of being rolled out across the globe, in Southeast Asia, there are several things needed to expedite immunisations and quickly curb the pandemic, as well as reduce the risk of illegal and counterfeit supplies emerging

As the world celebrates the recent approval of Covid-19 vaccines, questions remain as to how affordable and accessible they will be.

There also exists concerns over their safety given their fast-tracked approval and whether governments will make the vaccines mandatory or voluntary as the world witnesses the birth of a more contagious strain of the novel coronavirus in the UK. As United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres points out: “It is not with ‘vaccinationalism’ that we are going to defeat COVID-19. It is with international cooperation.”

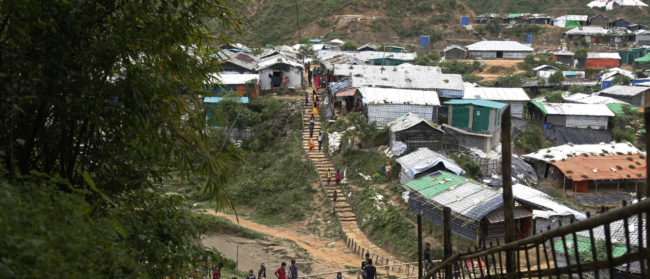

In Southeast Asia alone, how will we immunise more than 622 million willing and impatient people? Authorities must work together to expedite vaccines and curb the pandemic, or face the risk of illegal and counterfeit supplies.

In the first quarter of 2020, authorities in the ASEAN states confiscated fake medical goods such as masks and sanitisers, the market for which was fuelled by high public demand and limited, regulated supply during the pandemic’s rise. In this regard, Covid-19 vaccines can be stolen while in transit or storage or improperly reproduced for sale to the public.

The first priority for mass vaccination would be to secure and monitor distribution channels. The vaccines are currently imported by air-freight in Singapore, where Changi airport is positioned as a regional storage and distribution hub. Since the city-state adheres to strict laws, the greatest risk of vaccine interception by organised criminal syndicates will occur when they are transported to larger and developing neighbours.

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reports trafficking networks generally recruit pharmaceutical companies and state officials to exploit weaknesses. This means that authorities will have to remain vigilant to corruption opportunities in airports and medical facilities during the initial vaccine delivery. Fortunately, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine requires intense refrigeration which will limit the amount of facilities in the region that are able to store it (thus making it easier to secure and monitor).

However, Southeast Asian countries are in negotiation with other vaccine distributors that have lower refrigeration requirements, therefore increasing the amount of storage facilities.

Authorities must therefore encourage cooperation through instruments like the ASEAN Plan of Action in Combating Transnational Crime (2016-2025), and national authorities must share intelligence and resources in early stages to prevent the formation of illegal distribution channels. Failure to do this will result in a new wave of infections and health-related restrictions that will further impede ASEAN’s rapidly developing economies.

It is welcoming to see that Indonesia and Cambodia are pledging free vaccines for its citizens, which will likely reduce the potential of a black market forming

The second priority would be to ensure that vaccines reach their intended recipients in-line with national health policies. On the one hand, it is welcoming to see that countries like Indonesia and Cambodia are pledging free vaccines for its citizens, which will likely reduce the potential of a black market forming either online or within communities.

As more citizens are vaccinated, authorities must consider providing similar services to foreign residents and undocumented migrants to avoid a rise of xenophobia. For example, Singapore and Thailand have quarantined migrant workers in their dorms amidst a sudden wave of new infections. Similar measures could be implemented elsewhere in foreign resident communities under the rationale of protecting public health and vaccinated citizens.

If migrants cannot in the relatively near future access free or subsidised Covid-19 vaccines, national authorities will face the risk of increased demand for fraudulent identity documents, false Covid-19 vaccine certificates and alternative channels to acquire vaccines within their community networks.

Furthermore, as many public health priorities aim first to vaccinate health workers and the elderly, local authorities may need to be present at vaccine stations to ensure that there are no opportunities for corruption or theft.

For example, vulnerable population groups can be violently coerced or bribed for their designated vaccinations by a wealthy individual or one in a position of power. Should a person be incorrectly marked as having received the vaccine in official records, they could then pose serious health risks to the people around them and can lead to new infections or virus strains.

The third immediate priority for Southeast Asian authorities will be to counter a potential rise in counterfeit vaccines. According to the UNODC, Southeast Asia spends an estimated $520 million to $2.6 billion on falsified medicines per year, and falsified medical products are often produced in poor or unhygienic conditions by unqualified personnel.

In the Philippines, counterfeit rabies vaccines have found their way into legitimate supply chains and required entire batches to be quarantined. Should this happen with the Covid-19 vaccine, an influx of fake vaccines can have detrimental effects to public health and result in a more devastating wave of new infections and lockdowns.

Apart from finding its way into official channels, there are further avenues for Covid-19 vaccine distribution and official production which require international cooperation. For example, Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang pledged vaccines for the Mekong countries, and Thailand’s Siam Bioscience aims to set up local manufacturing facilities for AstraZeneca’s vaccine. In these instances, protection of the vaccine’s intellectual property and harsh penalties for offenders must be upheld in the name of public health and safety.

As such, local authorities also need to implement public information campaigns that encourage residents to only be immunised in authorised medical centres, and also be ready to quickly crack down on illegal, pop-up vendors who may appear either in communities or online.

One such counter-initiative was recently launched by the National University of Singapore for commercial use. DeepKey uses identification tags and artificial-intelligence-enabled authentication software to check products for counterfeits and has been proposed to be added to vaccine vials for remote testing. If applied, data can easily be tracked and shared between authorities.

As demonstrated, Southeast Asian authorities have many upcoming priorities to ensure safe and effective vaccines and prevent the formation of a shadow economy. This will specifically concern monitoring distribution channels, promoting international cooperation, and balancing rule of law with public health policies.

The people and governments of Southeast Asia have also made some remarkable achievements in minimising the risk of Covid-19 infections in the region and definitely serve as role models for other countries to follow. They should not lose the critical progress made to the development of black-market vaccines.

Zandre Van Straten is a Master of Arts in International Relations graduate from Webster University Thailand specialising in political and economic situations throughout Southeast Asia.