All Myanmar citizens’ names have been changed at their request.

As dawn breaks over a crowded market in Yangon, a student strolls in, browsing casually through the stalls of vegetables, fruit, spices and fish. Picking up an onion to inspect the quality of the produce, he doesn’t stand out in the crowds of people.

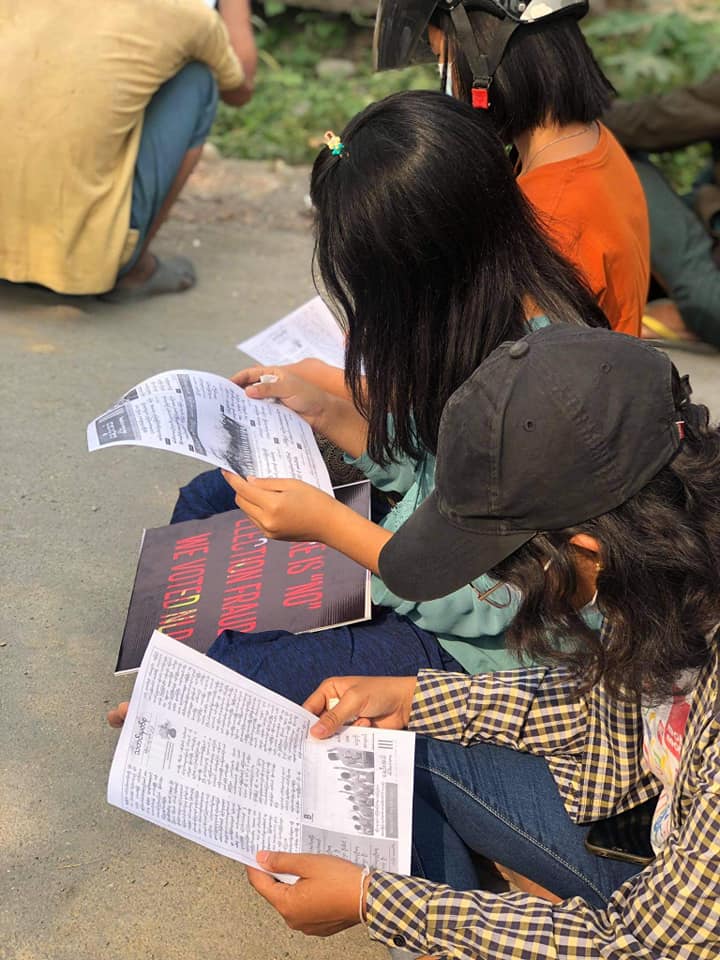

“One person has to go first and check, is it clear or not?” said Ko Naing, who became part of the underground newsletter movement in early April. “They just try to pretend they are buying something, and then they leave the info paper, the Voice of Spring.”

Pushed hurriedly into the hands of vendors and shoppers while students look over their shoulders, underground publications are surfacing amidst dwindling press freedom after Myanmar’s February 1 military coup. As open persecution of journalists rises in the country, these underground news outlets, usually only a few pages long for discretion or broadcast anonymously over the airwaves, are bringing information and motivation to the revolution amidst a new wave of press violence and censorship.

Ko Naing is one of a few leading alternative media sources in the wake of the February 1 coup. A journalism student, he founded Nwe u a Tha, or The Voice of Spring in early April, when he realised the growing need for news circulation that could withstand Myanmar’s daily internet shutdowns under the junta.

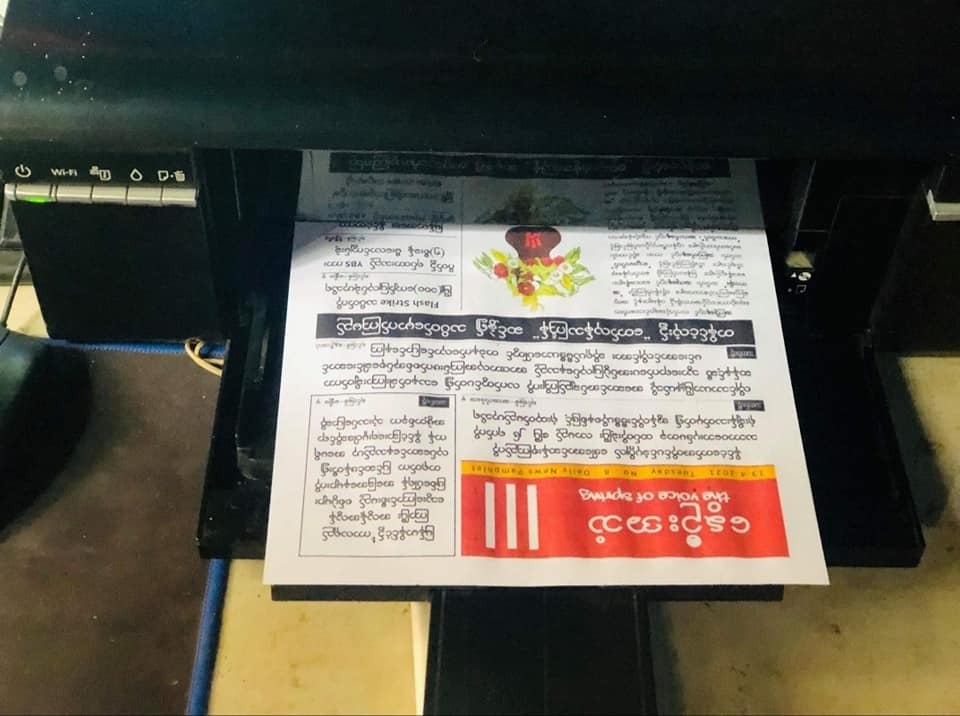

“I see that people really need information flow, and that’s why we’re getting back to the printing era,” Ko Naing told the Globe. A one-man team, he relied on the practical experience of his schooling, like creating a layout on InDesign and condensing international news on strikes and protests, but the secrecy required by the coup brought on several challenges for him.

“I need to think seriously to print it out. Where should I go? I have to find a place to print it out safely.”

After perfecting his one-sheet method to fit as much news as possible and choosing a secret location to print his first 100 copies, he took to the streets, nervously clad in a surgical mask and hat to hide his face. He says he was constantly looking over his shoulder, but the satisfaction is clear in his voice as he describes how The Voice of Spring was received.

“I was jumpy, really excited. I had [so much] tension checking the environment, because I have to be aware of spies,” Ko Naing said.

But that day, he was only met with gratitude from those who took his newsletter.

“They were really surprised,” he remembered. “Their smiles gave me so much energy. I can see that this is right, what I’m doing is right.”

That warm reception also included reminders to stay safe, as well as recognition from those who remember the underground publications of the 1988 uprising, the nation-wide strike following the devaluation of certain currency notes that ended in a strong military crackdown.

History serves as inspiration for many of the country’s citizen journalists, as is obvious by the reverence in Ko Naing’s voice as he talks about political prisoner and press activist, U Win Tin. The poet and journalist was jailed in 1989 for 19 years after working co-founding the National League for Democracy in 1988. While reading U Win Tin’s autobiography, What is Human Hell, Ko Naing was drawn to the blue shirt-clad icon’s struggle to create a journal in prison through taking notes from radio broadcasts.

“He really made me inspired with his life in prison,” Ko Naing said. “I still have [the internet] and the opportunity to go everywhere, so I need to do it.”

The Voice of Spring publishes daily, and while Ko Naing creates the digital soft copy alone for security, he’s gained a major virtual following with more than 9,000 likes on Facebook and plans to launch an SMS service this week.

Distributors and activists all over the country print from soft copies circulating on Twitter and Facebook, handing them out in their communities spanning major cities Yangon, Mandalay, Magway and Pyinmana, as well as locations in Mon and Kayah State. Some are even raising funds to buy their own printer.

“It really looks like a professional daily newspaper, that’s why I think we got so much support and participation from the people,” Ko Naing said.

The Voice of Spring isn’t the only outlet of its kind, as underground media outlets spring up across the country, their ranks swelling with students and labour unions moonlighting as citizen journalists. The crew at Molotov, another underground zine, are among them.

In a video by AFP, the staff of this other popular newsletter can be seen in the throes of the publishing process while smoking cigarillos on the floor, readying their supply for another day of discrete handouts at the markets and crowded areas.

Molotov co-founder U Chit Maung, who works under a nom-de-guerre paying homage to the independence-era writer of the same name, laughed as he recounted the publication’s journey to that point.

“It’s a long story, let me tell you,” he began.

Similar to Ko Naing, U Chit Maung is a student who was inspired by his studies to form a news outlet. He told the Globe his team saw an immediate need for information during the internet shut down and began publication on April 1.

“We noticed when the internet is shut off, the back-and-forth information disappears and people in their homes do not know what is happening on the streets, and that makes them fear more,” he said, adding that many in the low-media-literacy country can only access the state-run media’s narrative.

“To fight that back, we created Molotov.”

There is a need to give people motivation. So our newsletter features some articles and some text which gives people motivation, like poems

Popularised by active student and labour unions, Molotov’s connection with the General Strike Committee quickly created a network of eager supporters, both in the streets and on social media. The publication, which U Chit Maung claims has reached all states and regions in Myanmar, has contributors and reporters covering protest efforts and distributing in a wide array of cities.

Invited by a friend to assist in communications and distribution for the publication, U Chit Maung now works with Molotov to create the zine-style newsletter with basic printers and A4 paper. Their content ranges from an article series on guerilla warfare to international news, as well as information on protests, and finally, some more free-form content.

“There is a need to give people motivation. So our newsletter features some articles and some text which gives people motivation, like poems,” U Chit Maung said about their spring revolution prose.

Similar to the Voice of Spring, the publication also uses social media to spread digital copies. Despite the robust online following of nearly 2,000 followers on Twitter, many of the distributors and publishers of Molotov are unknown to even each other for security. There’s good reason for that, with U Chit Maung saying the military recently declared Molotov an unofficial and illegal publication.

“We cannot prepare any help for them [the distribution chain], because we are also running and playing hide-and-seek with the military,” he said, adding that Molotov has no plans to discontinue publication.

The attack on the underground was probably inevitable as official, mainstream media has increasingly come under attack itself since the first day of the coup.

Police and military arrests of journalists across the country, including two foreign correspondents in Japanese reporter Yuki Kitazumi and Polish journalist Robert Bociaga, are on the rise. Local reporters bear the brunt of this assault, with the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) reporting 43 journalists currently behind bars in addition to targeted violence at protests and elsewhere.

This persecution contributed to independent publication the Myanmar Times, founded in 2000, halting production on February 1, soon to be joined by other outlets as reporters across the country struggled to find safety. By late March, digital outlet Myanmar NOW declared Myanmar a country that “no longer has a single independent newspaper in [print] publication”.

“This is the worst crisis we’ve seen for the media in Southeast Asia in all our monitoring days,” Shawn Crispin, senior Southeast Asia representative for the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), told the Globe.

This dwindling press freedom is especially difficult to see for journalism educator Shin Nyein. The longtime instructor had watched the country’s independent media grow over the past ten years by teaching students from around the country. It was a far cry from how she’d first started her teaching career years before in 2014, in secret and under a false name at a time when it was still politically unsafe to openly train journalists.

Although she’s noticed a rising popularity of journalism, the media sector has a long way to go given Myanmar’s lack of independent outlets historically.

“We didn’t have journalism education before 2010, so no one thinks journalism is a professional career,” Shin Nyein told the Globe. A former student of hers is now one of the young reporters taking the risk to produce an underground publication.

“But there are some few who know about the values of journalism and know about the values of the news, and they are ready to take every risk to become that kind of profession.”

Myanmar’s growing underground anti-coup media movement isn’t just taking the form of ink and paper, it’s also hitting the airwaves.

“Let’s unite, we all won’t kneel and will fight the military coup …”

That’s how Nway Oo Guru Kyi opens his radio programme on Thursdays and Sundays, his voice cutting fast-spoken and confident through the radio waves on 90.2 MHz.

Despite having no reporting experience, the activist hatched his plan for Federal FM: Voice of the People with fellow rookie activists, technicians and journalists in the early weeks of the coup, ordering equipment after seeing the junta’s internet shutdown tactics.

As with the young newsletter publishers, the participants in this corner of the most recent citizen journalism movement lack formal training. But, credentialed or not, all hands are on deck in a revolution, getting out the information any way they can.

“In radio, it’s more powerful. You can hear the strength of our voice,” Nway Oo Guru Kyi told the Globe. “They cut phones, they cut the internet, they can do whatever they want. But for the radio channel, they can’t do anything.”

He’s now broadcasting his 40-minute programme in the cities of Mandalay and Yangon, talking with activists, sharing news about protest efforts around the country and sharing updates during emergencies. Thanks to digital platforms like Soundcloud and Mixlr, Federal FM can also keep the nation up to date and broadcast worldwide on the internet.

That reach could put a target on the backs of the programme team, and so members take special precautions to hide the location of their broadcasts, aware of the threat to their colleagues and family. For this reason, they don’t broadcast on a regular schedule, only announcing their programmes an hour or two ahead of time for fear the location of host Nway Oo Guru Kyi could be traced.

“It’s quite challenging for us, not only for the technology, but also for the security,” he said, sharing worries his loved ones could be kidnapped like countless others in the country. “If they know me, then my family will be at risk. If they want me, they can easily arrest my family.”

These citizen journalists are quick to point out press activists dating back to even the colonial era as inspiration for why they’re willing to take so many risks to distribute news. Shin Nyein says creativity in the face of risk is embedded in Myanmar’s press history, and publications are accustomed to pushing boundaries.

“A country like ours, we somehow knew how to work around it to get where we want in this established system,” she said. “This is a long struggle.”