The hopes of 8,000 people reverberate around Yangon’s Thuwunna Indoor Stadium in a blaring chorus of shrieks and screams. In unison, the crowd chants the name of their countryman, Aung La N Sang, as he trades blows with the formidable Vitaly Bigdash, a Russian reincarnation of Michelangelo’s David.

The two are fighting in a mixed martial arts (MMA) contest, one that Sang and his many fans in Myanmar hope will end in him being crowned the country’s first ever `world champion’ in any major sport – as far as anyone can recall.

Minutes into the contest, Sang stuns the undefeated Russian with a savage uppercut before flooring him with a lightning-fast hook. The wall of sound emanating from the sweaty fans grows louder still. Bigdash contorts his body into a series of unnatural positions, writhing around the mat in an attempt to avoid the avalanche of punches and elbows raining down on him. Somehow, he manages to weather the storm and the crowd is deprived of the first-round knockout it so desperately desires. But their support and Sang’s perseverance are soon rewarded.

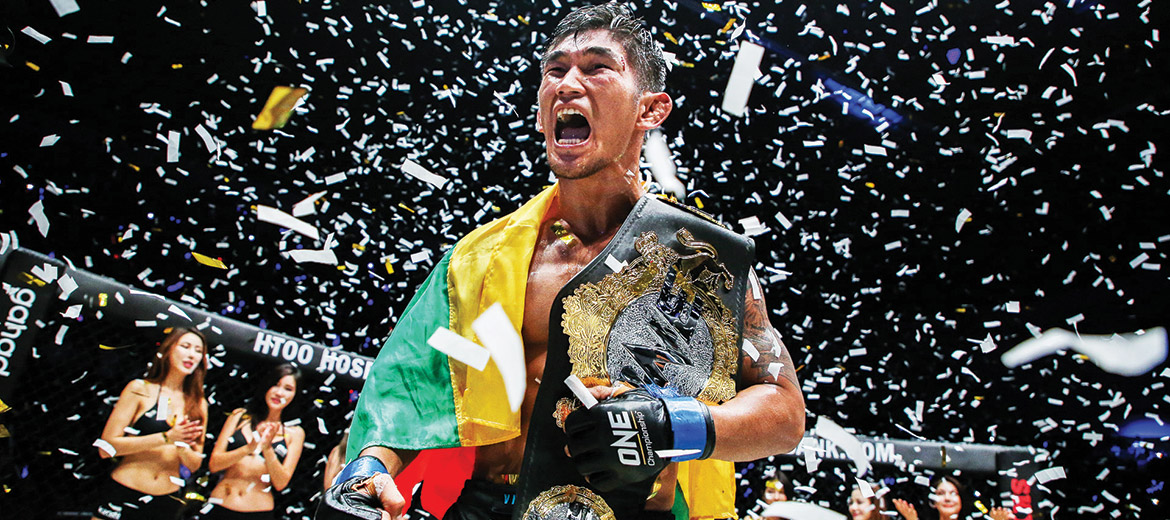

After five five-minute rounds, all three judges decide that Sang has inflicted the greater damage on his opponent. As the ring announcer bellows “your winner and new One Middleweight World Champion”, the `Burmese Python’ drapes himself in the Myanmar flag and raises a clenched fist in celebration, tears of jubilation streaming down his face.

“I’m not talented, I’m not good, I’m not fast, but with you,” Sang says while pointing to the crowd, “I have courage, I have strength, I have what I need to win a world title.”

It is a humble victory speech from a new hero of One Championship, a “world champion that clearly represents all of [the] great values of martial arts”, says Victor Cui, one of the organisation’s CEOs, in a post-fight press conference. As with many sporting world champions, however, he is the champion of just one organisation – one that is locked in its own fight for Asia’s rapidly expanding audience for this sport.

Along with its commitment to showcasing local talent, One’s brand is built around reverence for values such as honour, respect and humility, a marketing strategy that has helped the Singapore-based promoter become the leading MMA outfit operating out of Asia. But with the US-based Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) recently announcing its first-ever event in mainland China and demonstrating renewed regional ambitions since its $4.4 billion sale to a mix of American and Chinese investors last July, the fight to woo fans and the accompanying cash they bring in has only just begun.

Two weeks prior to Sang’s historic title fight, Singapore’s Indoor Stadium is playing host to a UFC event. By 3pm, the fan zone outside the venue is alive with anticipation. A diverse mix of expats and locals line up to get their hands on a $110 signed event poster or a $140 UFC jumper, while others test their punching speed, take note of company milestones on a lengthy exhibition wall or gawk at state-of-the-art Harley-Davidsons while sipping on free samples of Monster Energy drinks.

The main fight of the night pits the Brazilian brawler Bethe Correia against Holly Holm, an American who rose to fame after defeating household name and former Women’s UFC bantamweight champion Ronda Rousey in Melbourne in 2015. After the bell rings, two minutes pass before the pair make contact – a coming together that’s met by a wave of sardonic applause that just about manages to drown out the cacophony of boos swirling around a crowd hungry for action. One minute into the third round, just as people are beginning to write the event off as a certified anti-climax, Holm reacts to Correira’s taunts in spectacular fashion: shin connects with skull, and the Brazilian slumps to the ground. It’s a breath-taking finish to a night that rarely got the crowd on its feet.

The events typify the vastly different approaches taken by the two promotions: where One prefers to groom local talent and tailor its events to local markets, UFC stages its top talent wherever it goes, trusting that a global audience will appreciate good fights even without local allegiances. Despite their differences, they are both fighting for the same prize: media rights and sponsorships in a continent home to three out of the world’s top five countries most interested in MMA, according to market research firm Nielsen.

Joe Carr, UFC’s outgoing head of international and content, told Southeast Asia Globe that media rights make up 75-80% of UFC’s total revenue, a figure that jumps to 90% in the Asia-Pacific due to the low number of events staged in the region. “If you look at our Asia business, we’re making $40m-plus a year in media rights between Asia and Australia with limited overheads. We make small losses [putting on events] in Asia and we have a couple events a year, so all that money is going to the bottom line,” Carr said in a telephone interview from Las Vegas.

Media rights are the basis of One’s revenue and business strategy too, Chatri Sityodtong, One’s CEO and founder, told Southeast Asia Globe. He said the company bases its business model on the NFL, which earns $7 billion a year in media rights, a deal that equates to $200m per team. “Of course, we do look at ticketing, sponsorship revenue and merchandise also. But those are less of a focus,” he said.

In purely business terms, putting on events is essentially a means to an end. They are effective marketing tools for building a loyal fan base and increasing viewership, but they are also expensive.

“It doesn’t matter what promotion you look at, whether it’s UFC, One Championship, Bellator, whatever – the ticket revenue is never covering the costs associated with that event. You’re making money on the broadcast,” said Carr. “We’ve always used international events… to give fans a chance to experience the brand in person. We get more coverage in the media when we come with a live event than we would do otherwise. It’s just a way of putting the brand and the sport on the map in different markets.”

As it stands, UFC’s revenue is large enough to withstand losses made by putting on shows in Asia, but One, despite recording revenues that are in “eight figures and growing very rapidly”, is only “very close to profitability”, according to an interview Sityodtong gave to the Financial Times in June.

The Singapore-based company keeps a tight lid on its finances, and it is, therefore, difficult to accurately assess why it’s not turning a profit. However, given media rights are its main source of revenue, it would seem that it is not making enough money from these deals to cover the losses associated with putting on events. The catch-22 for One is that the most effective way of increasing the value of those deals is by putting on more events in order to increase its fan base and, hopefully by extension, its viewership.

Forecasts based on data gathered by Nielsen, Facebook and Repucom suggest that it certainly stands a chance of becoming profitable in the near future. According to that dataset, One expanded its broadcast reach from 60 countries in 2014 to 118 countries in 2017, as well as increasing its social media video views from 312,000 to 600 million and its social media impressions from 352 million to 4.8 billion during the same period.

UFC has done a wonderful job in the Western hemisphere, and I have nothing but respect for the UFC and what they have achieved there. But the reality today is there’s a global duopoly, right?”

As with a pair of trash-talking MMA fighters, however, both promotions claim to rule the roost when it comes to TV viewership statistics in Asia, which ultimately determine the value of the regional cable and free-to-air broadcast deals that make up the bulk of their revenue.

“UFC has done a wonderful job in the Western hemisphere, and I have nothing but respect for the UFC and what they have achieved there. But the reality today is there’s a global duopoly, right?” said Sityodtong. “We’re both market leaders in our respective territories. Whether it’s stadium attendance, penetration, fanbase, whatever – One Championship is significantly larger than UFC here in Asia.”

The idea of a global MMA duopoly has been accepted into conventional wisdom across Southeast Asia, and scrupulously peddled by One’s slick PR machine, which points to the data supporting its claim of regional hegemony.

A different Nielsen dataset made public by One shows that the live viewership statistics of its highest-rated shows in 2017 have eclipsed those of UFC’s most-watched shows in three out of four key Southeast Asian markets. In Indonesia, for example, One’s most successful event was watched on TV by 909,385 people, while the UFC’s reached 246,872. It was a similar story in Malaysia and the Philippines, while the UFC marginally edged out One in Thailand with 572,559 viewers to One’s 513,880.

However, three days prior to the UFC’s most recent Singapore event, the company published a report by the Australian consultancy firm Future Sports + Entertainment, which said that, in Asia, “the total hours viewed of UFC content [on TV] was 26 times more than the total hours viewed of the next-largest MMA promotion”, a figure that Carr said reflected the simple fact that the UFC puts on more events than One. Sityodtong called the report “hocus pocus”, and was not alone in noting the consultancy firm’s relative obscurity.

Gab Pangalangan, the editor in chief of the Philippine MMA website Dojo Drifter, said that the UFC, which he described as “the consensus cream of the crop of MMA”, had a much larger following in the Philippines despite One’s “bevy of local fighters”.

“Casual MMA fans would know about the UFC, while only the more hardcore fan would know about One. The simple fact that bootleggers are peddling fake UFC gear and not One gear means that the UFC branding bears more weight or is more well-known, even to casual fans,” he said. “UFC doesn’t have that many local fighters and still has a massive following in the Philippines; imagine how much that would increase if they were able to sign more talent and potential stars from the Philippines.”

While admitting the UFC would love to have an Asian champion, Carr said that the region suffered from a lack of MMA talent and the promotion would never put on local fighters for the sake of boosting attendances.

“In a perfect world, we’d have had a Singaporean fighter [on the Singapore card], but what we’ll never do is compromise the quality and put someone in there that shouldn’t be in there,” he said. “Part of [One’s] strategy is to have local fighters, and that works for them from a marketing perspective. But we pride ourselves on the quality of our competitions… if you watch something, you want to watch the best, right?”

However, according to James Goyder, a journalist who has covered combat sports in Asia for a decade, Carr’s explanation for the UFC’s limited number of top Southeast Asian fighters doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. In his eyes, One simply got there first.

“If you look at the Filipinos UFC have signed – Roldan Sangcha-an, Mark Eddiva, Jenel Lausa – Roldan is not even the best lightweight on his team, he’s the 4th- or 5th-best lightweight. The three or four best guys all signed with One. The opportunity was there for [the UFC] in 2011/2012 when One was just starting up, but they didn’t [take it], and One signed them on long-term contracts” he said.

One has done “very, very well”, especially given its short lifespan, Goyder added. The upstart organisation also has the backing of a number of powerful investors. In July, the company said it secured a “significant” investment from Sequoia India and Mission Holdings, bringing its total capital raised to $100m. The investment came a year after the company had raised an “eight-figure” investment from Heliconia Capital Management, a wholly owned subsidiary of Temasek Holdings, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund – an undeniably powerful ally.

Sityodtong also plans to expand into Japan and Korea within the next year and to take the company public within three years – a move he believes will help him realise his grandiose goals for One.

“I want all of Asia – its 4.4 billion people – to rally around One Championship as the first truly pan-Asian sports media property. And I think an IPO [initial public offering] will only further that cause,” said Sityodtong. “We want to hold 52 live events in every iconic major city across Asia. That’s the ultimate dream for me, the ultimate vision, where we truly become Asia’s first multibillion-dollar sports media property and part of everyday life.”

Ultimately, in the world of business, the numbers that matter are those on a company’s profit and loss statement. In this regard, at least, both the global superstar and the regional challenger are still trying to land the knockout blow in Asia.