For a region with a famous diversity of cultures, economies and interests, the motto of Asean – “One Vision, One Identity, One Community” – is rather ambitious. However, one thing most Southeast Asian countries do have in common is a staunch refusal by their governments to ensure a free press.

In Vietnam, 35 bloggers are currently serving prison sentences on trumped-up charges such as trying to overthrow the government. Since 34 Filipino journalists were killed during the Maguindanao massacre in 2009, another 21 journalists have been killed in the country. In regional nations from Malaysia to Myanmar, the state enjoys a stranglehold on mass media, with the ruling regimes and their friends tightly controlling much of the information that reaches the people.

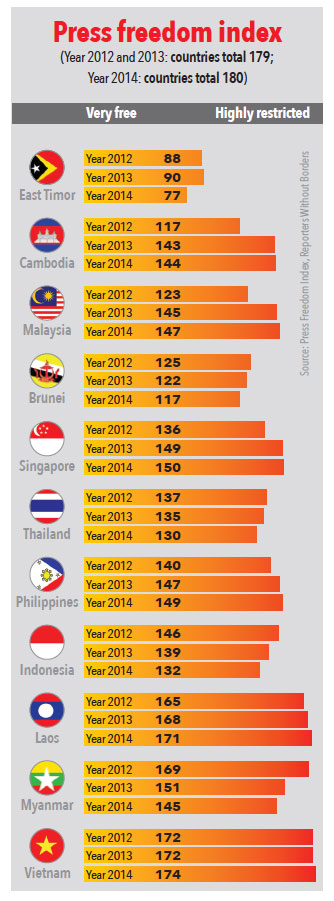

In the World Press Freedom Index 2014 by Reporters Without Borders, which reviewed 180 countries, East Timor was the only Southeast Asian country to crack the top 100. Brunei ranked 117th, followed by Thailand at 130th and Indonesia at 132nd. Laos and Vietnam were the least free countries in the region, ranked 171st and 174th respectively.

But despite efforts by governments in the region to control and silence the press, journalism in many countries in the region is thriving, due in large part to the rapidly expanding reach of the internet. State mechanisms to filter information have been slow to adapt to the digital age, leaving populations better informed than ever before.

In Cambodia and Malaysia, political information being shared online contributed to hotly contested elections that saw opposition parties make significant gains. In the Philippines, recent murders of journalists have not prevented the independent press from exposing damning cases of corruption among government officials. Even in Vietnam, where the government has taken a hard line against online dissent, bloggers continue to investigate the inner workings of the communist party.

“In the region generally, broadcasting is heavily state dominated,” says Oren Murphy, the Asia regional director for Internews, a US-based independent media development organisation. “With the internet, I think governments haven’t fully gotten their heads around it – initially because internet penetration was so low they didn’t care so much. But now that connectivity is expanding and people are being much more vocal online, [governments] are starting to care,” he said.

Malaysia, where laws have been passed against internet censorship, and almost 70% of the population has online access, is a “forerunner of what’s happening more broadly around the region”, according to Murphy. “The vanguard of online media can change the landscape,” he added. “Usually blogs themselves don’t have a large following. They put it online, it goes viral and then the government denounces it, which of course brings more attention to it and then even if mainstream media doesn’t cover the story, they cover the reaction to the story.”

Steven Gan, co-founder and editor of the political news website Malaysiakini, said that an increasing appetite for impartial coverage of current events allowed his website to build an audience of more than 300,000 paying readers.

“In general, we do a lot of things the mainstream media cannot do: reporting on corruption, reporting on police brutality, reporting on major demonstrations in the streets of Kuala Lumpur. People want to know what is happening and they want the media to be a check on the government,” Gan said.

Although the Malaysian government has held true to its promise to keep the internet free, which was made in a bid to attract investment from global tech giants, online journalists are not free from intimidation. “Instead of using repressive laws against independent media, you see a lot of tycoons and politicians suing independent media and bloggers,” Gan said, adding that the government has also made minor reforms to its control of mass media, lifting a previous law that required media companies to renew their licence every year.

While the courts are often the most effective tools to intimidate journalists, the Philippines is something of a paradox. It has both the most liberal media laws in the region and is one of the most dangerous countries in the world to be a journalist. Despite freedom of the press being enshrined in the constitution, endemic violence against journalists, and impunity for their attackers, has had a chilling effect on investigative reporting in the country, according to Luis Teodoro, a journalism professor in the Philippines and deputy director of the Centre for Media Freedom and Responsibility.

“The basic problem in the Philippines’ press nowadays is killings. Since 2010, there have been about 21 journalists killed for their work, so naturally this has an impact on how journalists are doing their jobs. A lot of journalists try to swagger it off, but a lot of journalists are also looking over their shoulder constantly and some of them have been more careful in the way they report,” Teodoro said, adding that out of 139 murders of journalists since 1989, only 11 have seen the murderers prosecuted and convicted.

Nonetheless, a strong public appetite for news about high-profile crime and corruption continues to fuel an aggressive print and broadcast media, Teodoro said. “Some journalists have armed themselves as well, there is a [media] group that has systematically armed their members. But besides being more careful, most investigative journalists have not been cowed by the killings.” With one of the highest percentages of social media users in the world, news scoops and exposés are having a wider reach than ever before, Teodoro added.

While the administration of Philippines President Benigno Aquino has widely respected freedom of the media, it has been slow to put in place measures to curb rampant attacks on journalists, Teodoro said. “The current administration is in a state of denial. For example, on the eve of the International Day to End Impunity, a presidential spokesperson said impunity has ended in the Philippines. A week later another journalist was killed,” he said.

As most governments in the region are fighting to keep in place systems that marginalise independent media, Myanmar has shed its distinction as one of the most restrictive media environments in the world. In 2010, Myanmar was fifth from the bottom of the Press Freedom Index. By this year, it had climbed almost 30 spots to 145th.

“In the previous system, we needed to submit all our articles to the censor boards and we could publish it only with their approval,” said Sann Oo, editor of The Myanmar Times, an independent weekly newspaper published in Yangon. “Now we are free to publish whatever we want and whatever we write.”

“But the government still has control over radio and TV,” Oo added in an email. “All the TV channels in Myanmar are joint ventures between government and private and most of the programs are entertainment. The main TV channel, MRTV, is being broadcast by the Ministry of Information and it is full of propaganda.”

As Myanmar recovers from years of totalitarian rule, both the government and the press are struggling to keep up with changes to the media environment, Oo said. “As the government dominated the media for more than 50 years, we are facing difficulties in getting information. Some of the ministries don’t want to deal with media and some don’t even want to talk to us. People are still afraid to talk to journalists, too. And in the meantime, most of our journalists are still young and they don’t have proper training.”

As Myanmar seemingly begins the process of expanding access to information, Vietnam has chosen an opposite tack, taking a hostile approach to battling bloggers and journalists at the online frontier. “Vietnam has stepped [up] information control to the point of being close to catching up with its Chinese big brother,” says the 2014 Reporters Without Borders report. “Independent news providers are subject to enhanced internet surveillance, draconian directives, waves of arrests and sham trials… It shows that the party is waging an all-out offensive against the new-generation internet, which it sees as a dangerous counterweight to the domesticated traditional media.”

Although Vietnam represents the worst case for freedom of the press in the region, governments are finding it difficult to curb the demand for independent information online, said Gan at Malaysiakini. “To put the genie back into the bottle will be very difficult. Press freedom is like a tube of toothpaste. Once you squeeze a little bit out, it is very difficult to put it back in.”