They left home seeking a better future, lured by a dream to be free from the shackles of poverty, only to risk returning with nothing or little to show for the years spent abroad.

While a common tale among migrant workers, domestic workers are even more likely to find themselves vulnerable with little chance of escaping exploitative behaviour by irresponsible and occasionally cruel employers.

Even for those who escaped, migrant domestic workers who seek shelter in government, NGO or embassy-run facilities may find themselves at another crossroads – to choose between reclaiming their rights or going home and starting anew.

It was slightly past 7pm on a Tuesday evening and a group of about a dozen women were sitting in two rows along a corridor.

Like every other night, they had just finished dinner and their chatter whiled away time spent at the Indonesian Embassy in Kuala Lumpur’s (KBRI) shelter.

Hidden out of sight from the bustling daily crowd of hundreds lining up to process their travel documents, the shelter comprises five bedrooms, a communal kitchen, shared bathroom, prayer room, laundry, and since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic – a quarantine section for newcomers.

Following an assignment roster posted on the wall, residents in each bedroom take turns carrying out the daily cooking and cleaning tasks. They were not permitted to purchase food at the public canteen.

Another sign listed 21 more rules to be followed, including a 10pm bedtime, no leaving the premises unless with permission, no switching rooms and no possession of electronic devices.

“We can accommodate a maximum of around 50 to 60 people. The condition is not ideal,” conceded KBRI KL counsellor Rijal Al Huda, in charge of its administration.

“One room can fit 10 to 15 people at once, some on bunk beds while others lay mattresses on the floor,” he said.

Quizzed on the ban on electronic devices, Rijal said it was intended as a safekeeping measure “to avoid things from going missing”. He was quick to add that calls or messages are accessible via a landline in the office and the shelter coordinator’s mobile phone.

Additionally, Rijal said the embassy is also renting another house that is used to shelter mostly mothers with children or those in need of more space.

Entering the embassy’s main gate, as written on a whiteboard in the guardhouse, there were 29 women at the shelter as of Dec 6 and three children. There were also another 12 women and three children in the second facility, bringing the total number to 47.

This year up to Dec 3, 321 women and children have been repatriated from the shelter.

Can’t afford lawyers

On average, Rijal said those with no outstanding cases could expect to leave for Indonesia within two weeks, while others in more “complicated situations” have had to remain in shelter for more than a year.

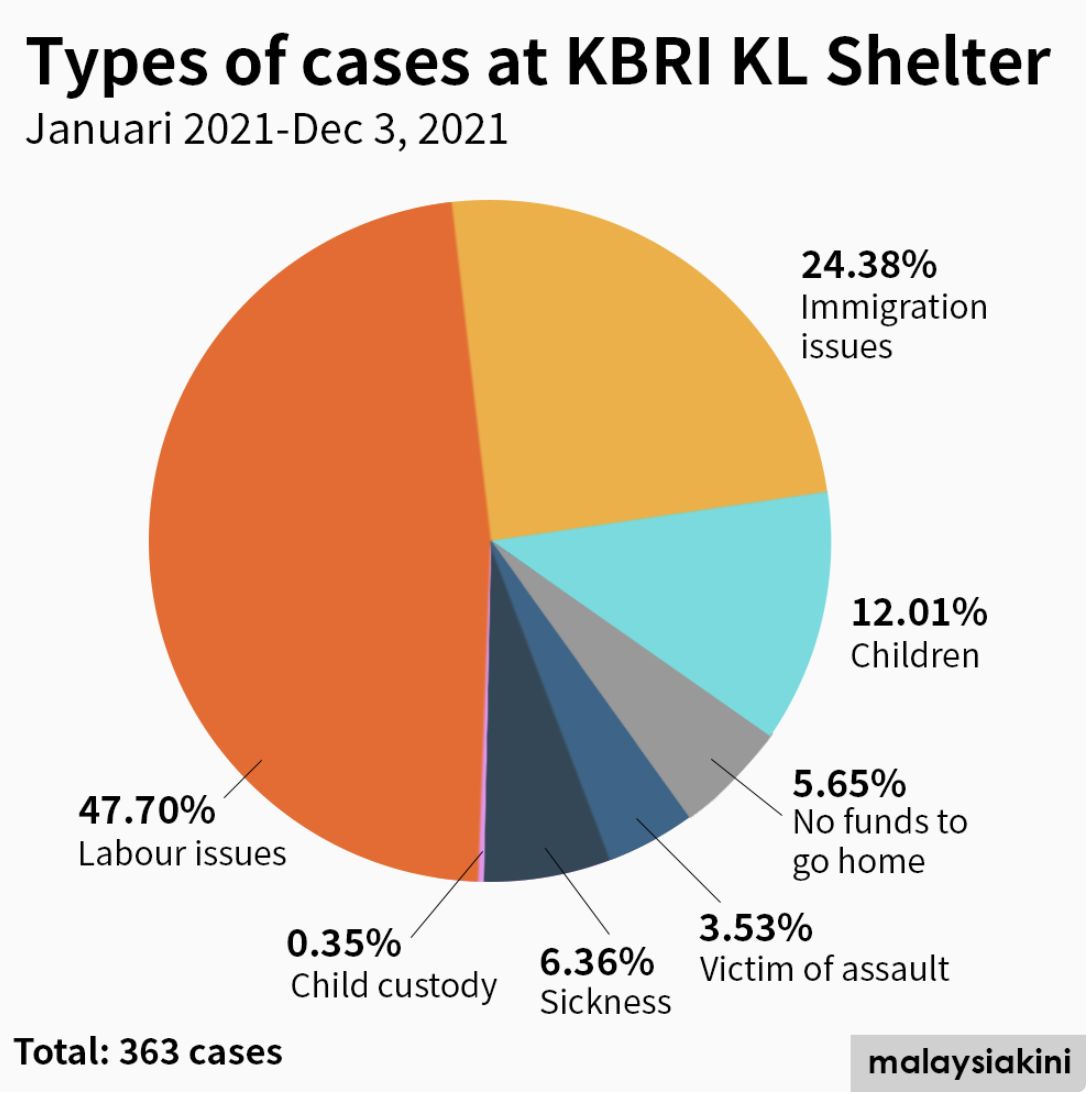

Of the current active cases, he said almost half, or 47.7 percent, involved labour disputes with employers, and about one-quarter, or 24.38 percent, had immigration issues, for example, missing official documents.

Both local and migrant domestic workers in Malaysia are currently excluded from protection under the Employment Act 1955 – a legal shortcoming cited by Rijal and migrant activists as a factor driving many women to flee an exploitative working condition, at times leaving behind their claims to unpaid hard-earned wages.

With a limited budget to hire lawyers, Rijal said the embassy has to be selective about which cases to fight.

“It is not certain that we will hire a lawyer. We will have to calculate the pros and cons. For some cases, we hire lawyers, but usually, in civil matters like unpaid salaries, we will try our best first (to seek redress) before we resort to hiring lawyers.

“First, we will try to contact the employers, the agents, and we also in some cases talk to the Labour Department,” he said.

Rijal said the situation became more complex when dealing with cases of undocumented migrants who are illegally employed here.

In one ongoing case, Rijal said the woman has been in the shelter for close to three years, going up against an employer who allegedly tried to “deny her existence”.

“We had to come up with creative ways of proving otherwise,” he added. “We have proven she was employed by the employer and right now, we are hiring a lawyer.

“But with the Covid-19 pandemic, the hearing has been changed multiple times already. It is heartbreaking to have them here for a long time, knowing that the facilities we have are not ideal,” he lamented.

Some are tempted to give up

Having spent years away from their families, in some cases leading to estrangement due to prolonged lack of contact, Rijal noted how some women requested to leave, even with outstanding salaries owed to them.

“There are at least three or four cases that due to the length of time… they just gave up. We have already assigned lawyers and the first step is to issue a letter of demand.

“After that initial step, they had to wait here for a long time and eventually, they asked us to send them home,” he said.

Malaysiakini previously reported on other ongoing claims for back wages handled by the Indonesian Embassy on behalf of women in their shelter, one of which allegedly amounted to RM106,000 for 12 years of unpaid work.

The outstanding amount varies between cases, to be claimed either via mediation, a Labour Court declaration, or civil proceedings, for any sum totalling more than six years.

Tenaganita officer Joseph Paul Maliamauv said one of the migrant rights group’s longest ongoing cases was filed on behalf of Nona* (name changed to maintain her privacy) – a young woman from Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara – seeking unpaid wages for work performed from 2013 until her escape sometime towards the end of 2017.

Little did Nona know that her newfound freedom turned out to be another ordeal.

It took her several more years of living in Tenaganita’s shelter before she eventually returned to Indonesia early this year. That too, with no certainty she would ever receive her hard-earned wages.

“She was being abused, and finally, she couldn’t take it anymore. She left the place with the help of a pastor who knew about us, so he took her to Tenaganita. That’s how she came to us,” Joseph said.

“With no end in sight, she wanted to go back home. ‘How long do I have to wait? I want to rebuild my life again’,” he said, quoting Nona.

Nona was promised a monthly salary of RM550 but never saw a single sen of her money, with RM9,000 or about 16 months’ pay from her four-and-a-half years in service supposedly sent directly by her employer to an account belonging to a family member.

She was being abused, and finally, she couldn’t take it anymore”

Joseph Paul Maliamauv, Tenaganita officer

On Aug 14, 2018, Labour director Misswandi Pardy said Nona’s claims for unpaid wages amounting to RM30,265.32 “be rejected and subsequently dismissed” as he argued that the Labour Court is not competent to hear the case because Nona was an undocumented migrant worker.

On July 19, 2019, after a year of multiple deferments and a change in presiding judge, a ruling was finally made that the Labour Court must hear cases involving undocumented workers.

“(However) her employer has appealed against the High Court ruling that she has a right to be heard in the Labour Court.

“That is where the case stands now. The appeal hearing has been postponed for over a year now,” Joseph said in an interview at his office in Tenaganita’s headquarters.

His office is filled with years of case files, documents and a small framed photograph of his late wife, well-known migrants rights activist Irene Fernandez.

Even if Nona’s claim was eventually heard in court, Joseph noted that with the time that had passed, there could be little evidence left to counter the employer’s defence that she never worked for them.

Nevertheless, he said the High Court ruling would still serve as an important legal precedent for claims by undocumented workers, despite a Labour Department’s alleged refusal to accept such cases.

‘My son calls me sister’

Coming into Malaysia through proper channels is also no guarantee of protection from being trapped in an exploitative working condition.

Mary* from Cambodia came to Malaysia in 2009 with a dream of saving enough money to raise her three-month-old son. Now, 12 years later, she stays on to fight for her hard-earned money.

“My boss didn’t pay me… I worked for nine years, but she would only pay me small sums of RM50 or RM100 or RM200.

“I asked my boss for my salary, and she said ‘you’re not going back so why need to keep so much salary?’ I said, ‘Never mind, I want to keep the salary myself. (Whether) I use or no use, it’s my problem because you already give it to me’,” said Mary.

For nearly 10 years, Mary said she was denied access to a mobile phone, cutting off ties with her growing son and family in Cambodia, as well as any chance of making new friends in Malaysia.

It was only sometime towards the end of 2020 that Mary said she finally had a mobile phone and her employer’s two children show her how to download TikTok.

From TikTok, Mary found another Cambodian domestic worker who, from what little information was available, managed to track down her mother.

Recalling their first phone call in a decade, Mary said, “Mother, father, I didn’t die. I really miss you.”

As for her son, Mary said he was raised by her mother. “He calls her ‘mother’ and calls me ‘sister’.

“I stay here. I no happy because my boss no good to me. My maam very good, my boss not good. When maam not home, he touch my everything [sic],” she revealed, instantaneously hugging herself.

With assistance from the Cambodian Embassy in Kuala Lumpur who was informed about Mary’s predicament at her workplace, Mary said she tried to negotiate with her “maam” but only to be told, “I let you play phone, why do you give problems to me?”

The Cambodian Embassy then attempted to engage with her employer. However, after the employer refused to discuss Mary’s release, she was rescued by a representative of the embassy and placed in Tenaganita’s shelter while waiting for a resolution of her case.

Malaysian authorities, through the Social Welfare Department, also shelter migrant workers and domestic workers believed to be victims of human trafficking, although Malaysiakini’s requests to obtain official data were denied.

With no formal recognition of their status as workers, the recruitment of domestic workers – including from Indonesia and Cambodia – are guided by bilateral agreements.

The agreements, in the cases of these two countries, were signed, thus lifting the recruitment bans imposed in 2011 over reports of widespread abuse.

They include stipulations for workers to be allowed to keep their passports and monthly salaries to be made into bank accounts, among others.

Malaysia is eyeing a January deadline to sign its latest agreement on domestic workers recruitment from Indonesia.

Human Resources Minister M Saravanan said that conclusion of the deal would also restart the entry of some 32,000 Indonesian migrant workers to fill urgent demands from the plantation and manufacturing sectors.

Indonesia has set the signing of an agreement as a condition before allowing its citizens to officially work in the plantation sector.

While the various new deals under discussion are meant to introduce safeguards for the future, it remains unclear how quickly the authorities will end the suffering of those who have suffered the double whammy of unpaid wages and a long stint in limbo while fighting to reclaim their losses.

This report was originally published on Malaysiakini and produced in collaboration with Indonesia’s Tempo Magazine. It is part of the Seafore Asean Masterclass Project and is supported by IWPR.