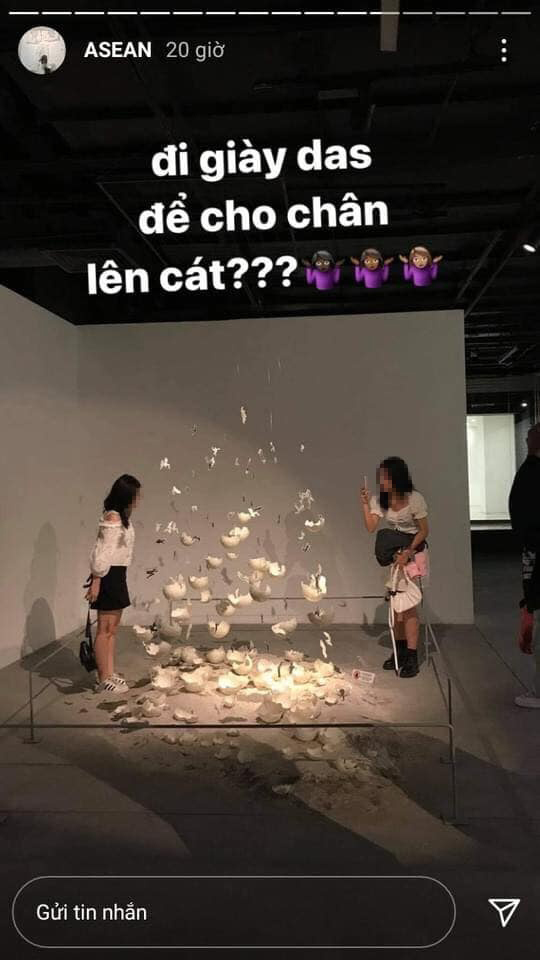

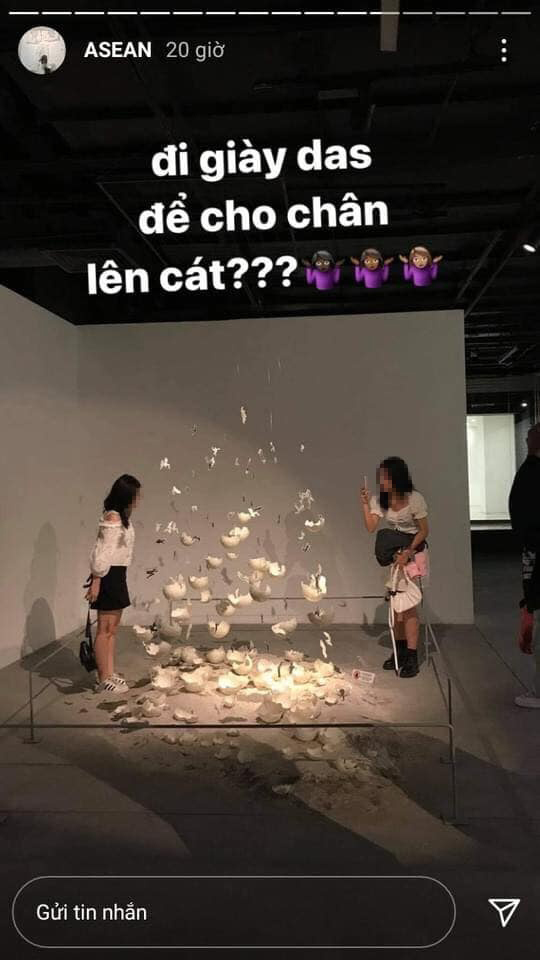

There are many clumsy shoe prints beyond the foot-high metal boundary, next to a small sign that screams out in all caps ‘PLEASE, DON’T TOUCH THE ARTWORK’.

They appear on the pile of sand that makes up Bu Bach Lien’s The Tale of Human, an installation at the 3rd ASEAN Graphic Arts Competition and Exhibition, which saw its final day at the Vincom Center for Contemporary Art’s (VCCA) this week.

But while the exhibition presented thought-provoking art, left behind was a room of shattered mirrors, cracked picture frames and broken dreams, as hordes of social media users threw caution to the wind as they hunted for that perfect snap.

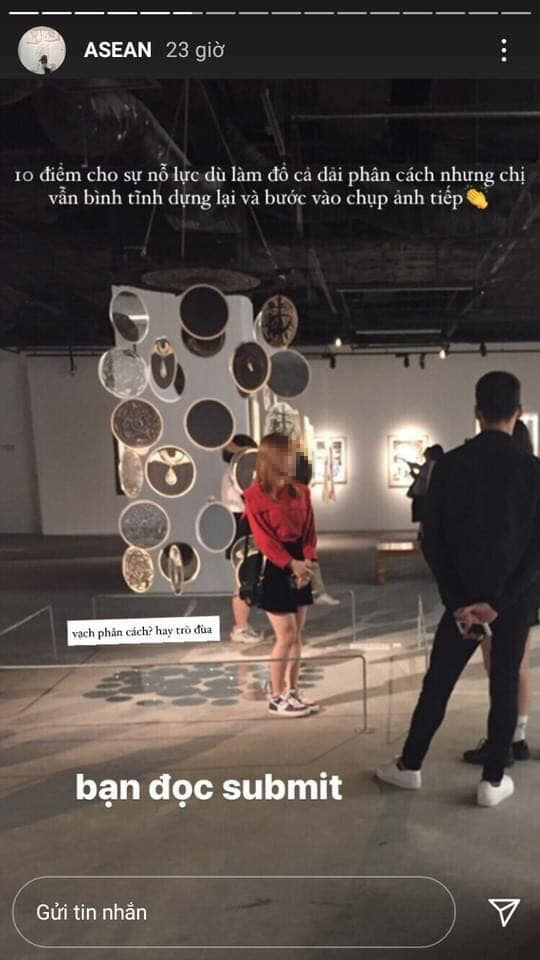

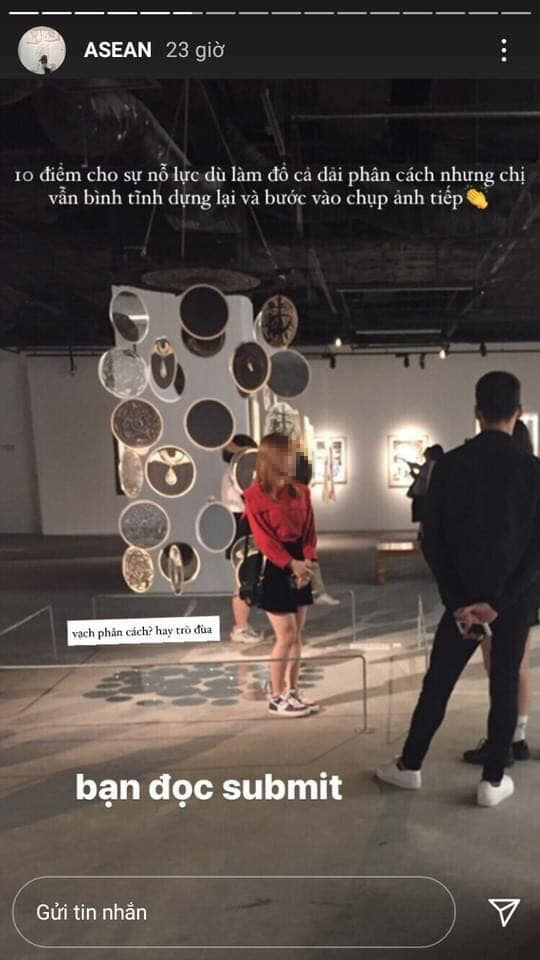

When earlier this month, one would-be influencer crossed the threshold into Hara Takashi’s VCCA installation, smashing three mirrors, VCCA was forced to release a public statement on its Facebook page reminding visitors the exhibits aren’t interactive. Far from a one-off whoopsie daisy, getting up close and personal with art has become an all-to-prevalent trend among Vietnamese social media users.

Since opening up in 2017, VCCA, which declined to be interviewed for this article, has been touted as a ‘check-in hotspot’ and virtual “paradise” of Hanoi youth – and it lives by that statement. Rammed from weekend to weekend, the space does a solid job of touting art to the public.

But, while most are satisfied with merely posing a respectful distance away from the artwork, looking wistfully off into the fluorescent lighting, many have taken their commitment to their social media feeds – otherwise known as ‘doing it for the Gram’ – one step further.

But Vietnam’s close-knit art circle appears to have had enough. Like a masked 4G-equipped vigilante, one person decided to take action into their own hands, and created the Instagram account ‘exhibitch_police’ to publicly shame art fondlers caught in the act.

The anonymous individual behind exhibitch told the Globe that the account was initially created out of anger following a trip to VCCA in which they’d seen young people inside the partitions taking pictures. The good samaritan told them to step out, but they didn’t listen.

Furious, exhibitch took photos and created an Instagram account to post them, accompanied by scathing captions. Noticing the wider trend online, exhibitch uploaded more pictures found under the hashtag #vcca, while also messaging users asking them to take their art fondling pictures down.

“Most of them saw my stories back then, but I had only like 10, 20 followers, so they kind of ignored it, some of them even told me to fuck off. So my harsh words didn’t work on them,” exhibitch explained.

But when exhibitch gained 16,000 followers virtually overnight, the account became harder to ignore. Suddenly, those who had previously scoffed were now sending messages, begging to have the pictures taken down. The shamed said they didn’t know the rules, which only annoyed exhibitch more.

“So I posted the rules. And I told them that the stories will disappear in 24 hours, which is too little time for what they did,” they said.

But like Icarus flying too close to the sun, the account was suddenly disabled – exhibitch had pushed too many buttons and been reported by too many people.

Exhibitch figured that was enough, it went viral, people saw it, maybe they won’t be so brazen with the artwork from now on. But a friend created a new account on their behalf. “They told me I need to continue, like the ugly reminder that if they don’t do their homework, they will be noticed here,” exhibitch said.

One of the everyday Instagrammers that came under exhibitch’s scrutiny was 18-year-old Nguyen Tri Cuong.

Nguyen is a highly fashionable Vietnamese Instagram user, with his shaven head and large silver statement pendant shaped like a tire. In his offending pictures, Nguyen is standing between a series of woodcut prints on cloth called Still Life With Apples by Indonesian artist Syahrizal Pahlevi, and gently (sort of) parting them with an outstretched arm and an arched back.

Nguyen explained that he hadn’t initially realised his mistake. “It was my first time visiting VCCA, and I hadn’t read the rules carefully,” he told the Globe. “Some rules weren’t mentioned on the board, and guests have to notice and do them themselves. That’s why I accidentally made some mistakes.”

But while Nguyen’s contrition for his sins is evident, he said he’d rather exhibitch’s scorn be more civil.

“I agree [that the rules should be followed], as I know that some works of art can break if touched. Works of art are most beautiful when we see them from a distance. However, I would be polite to warn people against making mistakes.”

Vietnam’s youth-led art fondling craze isn’t unique to VCCA. Manzi, one of the leading independent art spaces in Hanoi, has seen two paintings ruined by people taking pictures in their nine-year existence.

“We had a big lacquer painting by a local artist in Vietnam that was really expensive. Suddenly, we noticed a crack in the painting. When we looked at the CCTV, we saw a girl wearing a ring who tried to touch it, like that,” said Manzi founder Vu Ngoc Tram as she swept her hand through the air as if running it along the length of a picture.

Every Monday, Vu and her team clean footprints off of the white walls in the gallery. How or why footprints end up on the gallery wall remains a source of great consternation among staff, but widely believed is that one foot is propped against the wall to anchor people taking chic pictures. Manzi staff constantly patrol the area to ensure no one gets handsy with the goods, but many visitors just don’t listen.

“It doesn’t work. They say ‘ok’, and then when the staff turn around, they just touch it again,” said Vu.

It used to be that Manzi clientele would have a coffee, look at the art and maybe take a few snaps on their way out. These people still exist, but the clientele there just for picture-taking purposes has increased. Vu says that around 10% are there to take pictures with the art, to hold discrete fashion shoots with quick costume changes in the bathroom, and, sometimes, accidentally break something.

“This is the main problem,” Vu said, tapping her smartphone. “Insta, Tik Tok, and Facebook. Insta for young people is wanting to be seen as deep and trendy. Insta and Facebook did that for a lot of young people.”

Vu’s probably right, at least when it comes to the reason why everyone is touching artwork. In a population of 95.54 million, an estimated 65 million Vietnamese are on social media – that’s 67% of the population with twitching thumbs. Instagram is the fifth most popular app, with 46% of social media users of ages 16-64 using it and hungry for content.

Ian Paynton, cofounder and managing director at Hanoi-based content marketing agency We Create Content, explains that trends turn over extremely quickly in Vietnam.

“They leave as fast as they arrive,” he said. “Once the online population has had their fun, they are very quickly on to the next trend.”

Photoshoots in chic cafes are an everyday event. Flash in the pan trends like “my girlfriend is a rice cooker”, where teens take their mum’s steamer on weekend getaways, or lay out marriage proposals with tealights, also aren’t unheard of.

“From what I can see, young people in Vietnam don’t only observe the trends, but get lots of pleasure from actively participating in them, or ‘catching the trends’ as they call it.”

In Vietnam, the cultural phenomenon is called song ao, or “virtual life”. The originators of the trends were titled “hot boys” and “hot girls”, and they were Vietnam’s first influencers. But now, everyone does song ao, whatever age or creed.

The term first cropped up in 2007, but didn’t get big until 2015. Think of that POV video, when one person in a cute outfit leads another person by the hand on an idyllic beach to the backdrop of sickly pop music – that’s song ao.

“No matter where you go in Vietnam, there are people dressed up as fashionistas posing for hundreds of photographs destined for their social media channels. And if that bubble tea is not on social media, then it didn’t happen,” said Paynton.

While perhaps more exaggerated than in other countries, there isn’t anything particularly unique about this Vietnamese trend – in fact, the desire to ‘flex’ on social media may just be the single uniting factor crossing youth-culture worldwide today.

Last year in Kuala Lumpur, an 18-year-old Qisya Mirza was shamed for holding an art installation at a national art museum. She explained on Twitter that the incident was a misunderstanding, having seen it laying on the ground and wanting to put it back on the wall.

“Then my friends started taking pics of me without me noticing. Then after I realized they were taking pictures I just went along,” she told BuzzFeed in 2019, adding that she “had no intention on posting it on [her] Instagram” at first.

Misunderstanding rules and convoluted excuses has become tired cliche to exhibitch_police. But there was hope to be found in the account’s messages to the Globe. Hope that Vietnam’s social media users will learn something from the event; hope that, next time the vigilante attends an exhibition, they won’t have to see people kneading the artwork.

“This account has given me the chance to talk to not only professionals, but many people who really care about art. We talk about how to measure damage, and how to make new rules to protect it,” said exhibitch. “My account just has a tiny impact on art education. Even if it’s an ugly one, I don’t mind.”

Follow Hanoi-based Ashley Lampard for more hot takes on Vietnam on his Twitter account.