All political parties and their leaders are prisoners of history.

In the long term, those that adapt to the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune will endure. Others will go to the wall.

To assess the future of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), the “Grand Old Party” of Malaysia, we need to excavate its history. Until being unseated in the general election of 2018, for an unbroken 61 years of rule the party deftly juggled politicised identities to maintain its hold on power – a game inherited from the British colonial period.

The independent governments in both Malaysia and Singapore have evolved as what the historian Karl Hack referred to as nations-states that resist a single postcolonial identity. Today, on the 77th anniversary of its founding, these pluralistic identities have left it struggling to maintain roots in the country’s shifting political landscape.

After capturing Malaysian hearts and minds for so long, UMNO may have lost its long-held status as the natural party of government. Following high-profile corruption scandals and shifts in voting behaviours it will take drastic measures for the party to maintain a grip on political relevance.

Anti-colonial origins and an ethnic schism

UMNO was founded by nationalist politician Onn bin Jaafar in May 1946 to contest the formation of the federated ‘Malayan Union’ proposed by the British that same year and force the Malay sultans to break cooperation with the colonial power.

The British depended on Malayan exports to restore their battered economy after World War II, and so the Colonial Office in London hatched up the Union plan to federate the nine Malay states as a single political entity. This would have granted equal citizenship to Chinese subjects of empire – a neo-colonial policy described as ‘unite and quit’.

In 1945, when the colonial powers ousted the Japanese occupiers and returned to their former domains – British Malaya, Dutch Indonesia and French Indochina – they found highly unstable political terrains. The Japanese had offered numerous nationalist organisations the means to seek independence by violent means, which led to savage conflict in the former Dutch and French territories.

In Malaya, the British rationale was that communal harmony would guarantee efficient production from tin mines and rubber plantations. As soon as they got wind of the Union plan, Malay nationalists understood immediately that they faced a grave threat to their special status as ‘Bumiputera’ [sons of the soil]. Jaafar created UMNO a month later to prevent, as he put it, the “extinction” of the Malay race.

UMNO achieved a spectacular success tearing up the British plan and thus safeguarding special rights for Malays. The new party captured Malay loyalties and, ironically, became a guarantor for British interests as colonial Malaya edged towards gaining independence.

After 1948, the majority of Malays and, under the leadership of the aristocratic Tunku Abdul Rahman, UMNO backed the British ‘Emergency’ war to crush a Communist insurrection led by Chin Peng and the Chinese-dominated Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA). The Tunku’s strategy of forging bonds with conservative Chinese and Indian parties as well as the British paid off – the UMNO-controlled ‘Alliance’ won the 1955 federal elections and led Malaya to independence in August 1957.

But UMNO’s masterplan for independence would always be a delicate balancing act.

As with the British colonial apparatus, UMNO’s leaders asserted privileged ethnicity and simultaneously reproduced the colonial practice of managing antagonistic identities in a controlled political arena through low level coercion. The UMNO model secured the power of the Malay elite while offering contacts and contracts, plus economic and cultural space to other ethnicities.

The first signs that this model could fracture emerged from within the Malay community. They would later culminate in the traumatic 13 May riots of 1969 and the sweeping New Economic Policy (NEP) which addressed the persistent poverty of many Malays in rural areas.

By 1950, UMNO party founder Onn Jaafar – the so-called ‘Gandhi of Johor’ – had left the organisation when its leaders refused to open membership to non-Malays. A year later, in 1951, a Muslim faction in the party split away to form the Persatuan Islam sa-Tanah Melayu which would later become the Pan Malayan Islamic Party, which is still known as PAS.

The deepest problem for UMNO was twofold. Independence had not solved the problem of Malay poverty and, for many devout Muslim Malays in rural communities, UMNO appeared insufficiently respectful of their faith.

On the other hand, PAS – under the leadership of party President Burhanuddin al-Helmy – successfully focused on securing the support of the impoverished and religiously devout Malay communities . The split between UMNO and PAS set the tone for deep fissures in Malaysia’s political landscape and the two parties engaged in a succession of skirmishes that in the long run transformed political engagement into a struggle over religious identity.

The Mahathir era

The year of 1981 saw a key landmark in Malaysian political history – the election of the first non-aristocrat, Dr Mahathir bin Mohamed as Malaysia’s fourth prime minister. Mahathir, a former medical practitioner from humble beginnings, would dominate Malaysia for 22 years with policies that transformed a stuttering economy. Between 1988 and 1997, GDP grew close to 10% per year pushing Malaysia into the ranks of the ‘Asian Tigers’.

Before taking power, Mahathir had long bemoaned the imperilled status of Malays. In office, he was uncompromisingly assertive if not outright dictatorial. When his rule as prime minister and party president was challenged in 1987, he retaliated by dissolving UMNO and forming a new party UMNO Baru [New UMNO], which continued to hold power.

The ‘Baru’ was dropped in 1997.

In that same decade, current Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim emerged as a powerful and divisive figure in the ruling party. By 1993, Anwar was deputy president of UMNO and deputy prime minister. When Malaysia and other Southeast Asian countries were battered by a severe economic downturn in 1997, Mahathir and his deputy argued bitterly over solutions to the crisis.

This suddenly escalated when, in the following year, Mahathir had Anwar removed from office and expelled from the party on trumped-up charges of corruption and sexual misconduct. Like a tropical storm, Anwar’s downfall and imprisonment profoundly unsettled the landscape of Malaysian political manoeuvring, introducing new schisms and a mishmash of unstable allegiances.

The scandal provoked the first large-scale, popular demonstrations under the banner of Reformasi [reform], which led to UMNO losing the majority of the Malay vote for the first time in the 1999 General Election, and only just hanging on to power thanks to their coalition partners in Barisan Nasional.

Whereas the fiery Reformasi demonstrations inspired many Malays to swing their support to the Islamist PAS and Anwar’s newly created party, KeAdilan (the People’s Justice Party), they also evoked fears among the Chinese electorate of a repeat of the traumatic 1969 riots.

That didn’t happen – but in the new century, it was the spectre of corruption on an unprecedented scale that would deepen UMNO’s political woes and shatter the party’s grip on even its most loyal supporters.

The 1MDB scandal as a poison pill

The momentum for Reformasi ground to a halt when Mahathir stepped down in 2003.

His successor, Penang-born Abdullah Ahmad Badawi from a prominent religious family, successfully positioned himself as a mild-mannered moderate and brought UMNO and the Barisan Nasional coalition its biggest triumph in the 2004 General Election.

This victory would bring him little security within the party – by 2009 he was pushed out of the prime minister’s seat by a Mahathir-backed campaign within UMNO.

Whatever reprieve to be found in these events would prove short-lived. For despite its dissolution, the Reformasi movement had sown the seeds for a new wave of popular protest that would emerge years later and bring arguably the biggest-ever numbers of protestors onto the street – including Mahathir himself.

It was the rise of a politician with deep roots in UMNO that would unleash the greatest crisis in the party’s history. Najib Razak is the son of the architect of the NEP, Abdul Razak Hussein, and rose rapidly in the party after the death of his father. From the beginning, Najib seemed to lack the gravitas of his prestigious family. As minister for defence, he’d been implicated in allegations of corruption but was elected prime minister in 2009.

His ‘1Malaysia’ campaign emphasised integrity – but would lead to one of the biggest money-laundering scandals in history almost a decade later, the worst crisis in the history of UMNO from which it has never recovered.

The 1MDB scandal, where top officials looted money from a state investment fund for their own personal expenditure, and the later, spectacular fall of Najib Razak – now serving a prison sentence – stemmed from Razak’s need for massive funds to pry UMNO from Mahathir’s tenacious grasp.

While the stories of Razak and his wife’s spending on luxury goods are legion, avarice alone could not explain the billions being circuitously diverted from public funds into Razak’s accounts. It is widely believed that, having seen the ouster of his predecessor Abdullah, Razak needed his own billions to secure his hold over the party and therefore his premiership.

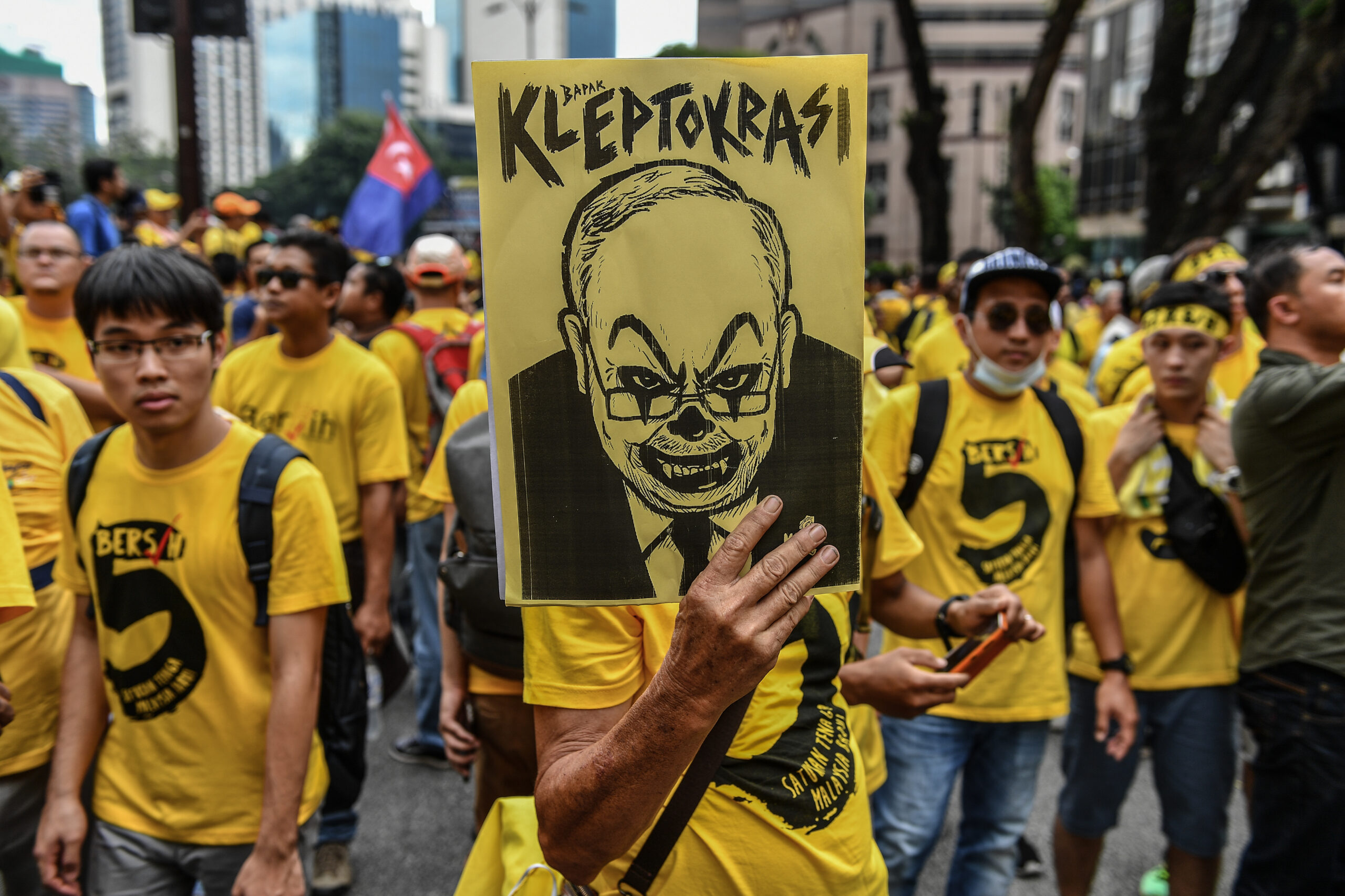

The odour of corruption that wafted so pervasively among the UMNO elite under Razak was one of many factors that inspired a revival of ‘Reformasi’. This came in 2006, under the banner of ‘Bersih’: The Coalition for Clean and Fair Elections, an alliance of non-governmental organisations.

Riding the wave of vibrant popular protest, the nonagenarian Mahathir now made a remarkable comeback. In August 2015, he and his wife Siti Hasmah openly joined the Bersih 4 Rally for two days – even though the event was dominated by Chinese Malaysians.

Denouncing Razak as a “prime minister who came from Bugis pirates”, Mahathir formed a new party, the Malaysian United Indigenous Party (BERSATU).

Determined to oust the man he had backed to replace Badawi in 2009, he joined forces with parties who were hitherto sworn enemies – including Anwar Ibrahim’s PKR – to form the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition.

This political fracturing culminated in the astonishing election results of May 2018, which saw unprecedented losses for UMNO. By then, the poison of the 1MDB scandal was leaching through the Malaysian body politic and deeply corroding Razak’s fragile reputation.

1MDB is by no means the only scandal that has tainted Malaysian politicians. But the scale of the corruption was so excessive as to be beyond the pale for many. Entire constituencies that had been willing to put up with many of UMNO’s past misdemeanours and were – and still are – vehemently opposed to supporting Anwar and his allies, voted against the “Grand Old Party”.

On 10 May 2018, the 92-year-old Mahathir became the world’s oldest serving state leader and the first Malaysian prime minister not from UMNO. The party’s six decades of rule was ended and there was a mass exodus of lawmakers and rank and file party members.

Anwar was given a full royal pardon and returned to parliament.

Uncertain future

Despite the turbulence that had preceded it, the 2018 General Election was a shock for many Malaysians.

Since 1957, generations have been brought up with the implicit understanding that UMNO and government were interchangeable concepts. But 2018 allowed Malaysians to truly believe that a government without the party was possible.

Overnight, UMNO became just like any other party, not the political bulwark of power it had been for over six decades. Entire communities, patronage dependencies, business loyalties and institutional relationships built over three or more generations were uprooted and dismantled.

Even with Razak now imprisoned, the taint of corruption that clung to UMNO has never been scrubbed clean.

The party’s losses continued in the past November election, in which it suffered calamitous results leaving it with a paltry 30 seats. Nevertheless, the complex calculus of the 2022 election results, with no one securing a majority, led to the unlikely scenario of UMNO sharing power in a ‘unity government’ with Anwar and the PKR – despite winning the least number of seats in its history.

The current UMNO President Ahmad Zahid Hamidi is himself facing corruption charges, and has dealt with his opponents within the party with the kind of crude brutality that will likely elicit further subdivision of existing support.

Therefore, it is likely that UMNO will lose even more ground in the short-term with the coming round of state elections, where it is expected there could be many loyalists who may choose to boycott the vote or vote for the opposition. Whether these short-term losses are a prelude to long-term decline is a different story and we should be cautious about such a hasty prognosis.

If Malaysia’s ‘Grand Old Party’ can be seen to cleanse itself of corruption-tainted individuals, including current President Zahid – no one can discount its enduring capacity to bounce back as the dominant party. Or at least one that can win the most Malay-majority seats.

But UMNO’s stranglehold on Malay society could be truly diminished to irrelevance if it is unable to purge the poisonous inheritance of 1MBD, and if it remains out of power long enough – notwithstanding the uneasy current arrangement with the Anwar administration – for a generation of voters to grow up with no memory of UMNO as the governing party.

About the authors:

Danny Lim is a freelance journalist and writer who has worked for many Malaysian and international media organisations on a wide variety of issues, most frequently with the BBC, as well as Al-Jazeera and The Edge. He is the author of ‘We Are Marching Now: The Inside Story of Bersih 1.0’ (September 2022), which tells the behind-the-scenes history of the biggest street protest movement in Malaysia.

Chris Hale is a documentary producer/director who has worked extensively in Malaysia and Singapore and is author of a number of books including ‘Massacre in Malaya’ (2013) and ‘A Brief History of Singapore and Malaysia’ (2023).