The politics of conservation in Cambodia

Environmental conservation is a political tightrope in Cambodia. The conviction of Mother Nature activists shows the consequences of pushing things too far, while the close relationship between major NGOs and authorities illustrates the risks of too much compliance

By Alastair McCready

Additional reporting by Andrew Haffner

Flanked by lush woodland on either bank, the whir of the engine keeps conversation clipped as a speedboat carrying eight men cuts through the broad and otherwise empty Preak Piphot River in southern Cambodia.

Turning off the mainstream, they disembark on a muddy beach – two armed with Chinese-made AK-47 lookalikes, another with a bolt action rifle, others with machetes – as they begin their patrol through a small community of wooden bungalows, rice fields and territorial dogs.

The mid-June rain falls as the men enter a narrow track under the forest canopy. It’s a two-hour walk uphill before they reach a fork in the road.

“Da, it’s 50% we find something if we go this way. But 100% we find something if we go this way,” group leader Roman said, dropping in words from his native Russian, while communicating with his patrol team in a mix of simple English and broken Khmer.

“You can tell by the tracks.”

The humid surroundings of this forest path in the southern Cardamom Mountains are a long way from his home city Yekaterinburg, 24 hours east of Moscow in central Russia’s far flung Ural Mountains. The 35-year-old Wildlife Alliance ranger leads a team of Military Police Gendarmes, Ministry of Environment judicial police and civilian park rangers living at the nearby Stung Proat ranger station.

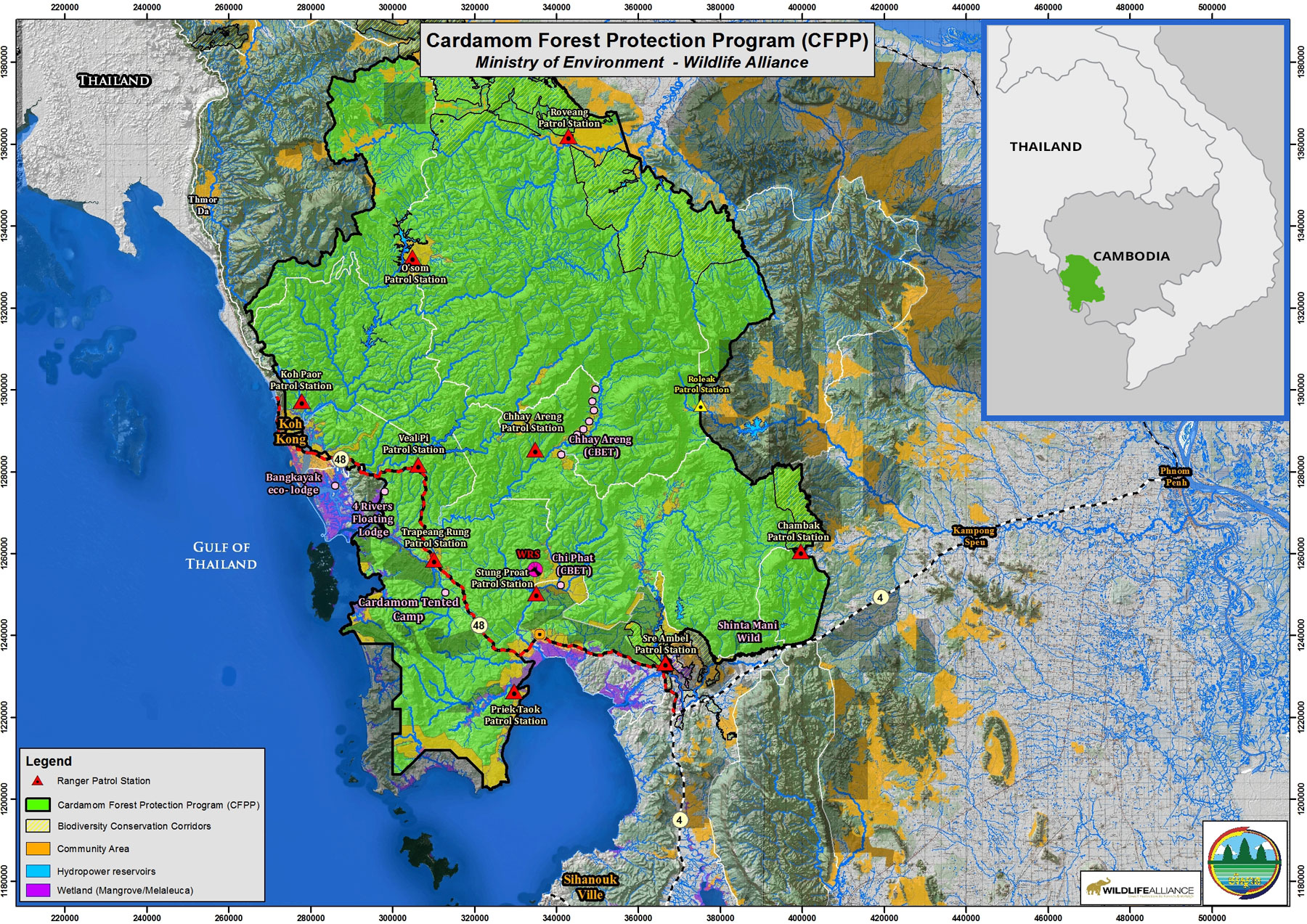

The men all live at the remote, riverside outpost – one of 10 across Koh Kong province from which government-appointed rangers patrol vast swathes of protected forest under the supervision of a Wildlife Alliance ranger as part of an agreement with authorities.

The Cambodian government and a conservation NGO make for unlikely, often uneasy, bedfellows. A global deforestation hotspot, Cambodia has in the past week alone seen the US end its $21-million aid programme dedicated to protecting the increasingly degraded Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary over continued logging, as well as three young conservationists from now-disbanded group Mother Nature being sent to Prey Sar prison on pre-trial detention.

But this is all part of a conservation political tightrope that must be walked in the Kingdom, one in which pushing too far can see you removed entirely, while, at the other end of the spectrum, too much compliance risks rendering you complicit.

Back in the Cardamoms, this balancing act plays out as recent developments mean Wildlife Alliance leaders must carefully navigate their government relationship to preserve the integrity of their 500,000-hectare carbon credit conservation zone, the Southern Cardamom REDD+ project.

On March 2, a new sub-decree signed by Prime Minister Hun Sen opened up 127,000 hectares across eight “protected areas” in Koh Kong province, including large sections of the Wildlife Alliance REDD+, for “distribution to the people”.

The process would transfer public lands to private hands and, as seen in areas where this has already happened, could set the woodlands on a fast track to deforestation and development.

The sub-decree is an act you might expect to put Wildlife Alliance in direct conflict with the government. But the organisation’s close working relationship, key to its maintaining unparalleled access to the forest, instead places it in an awkward bind, needing to turn a blind eye to the destruction the land transfer threatens to wreak.

Three months after the sub-decree’s passing, this dynamic unfolds on the ground as Roman exits the forest, the sun setting as the patrol nears an end. They’ve uncovered a small-scale logging operation inside, the perpetrators escaping before they could be apprehended, leaving behind equipment and the remains of their lunch – a civet, cooked in a brown sauce and packed into plastic containers, bones and all.

Roman’s patrol team enters a freshly logged area of charred tree stumps on the forest’s outer edge, a single wooden home on stilts now sitting in the middle. Until two or three months ago, he says, the area the size of 20 football fields was still lush forest.

“At first I was angry with the people for cutting down the trees. But I had an old map of the area,” he said, referring to the parameters of the land he’s been assigned to protect, adjusted since the sub-decree.

“That was before I knew [the area was no longer protected]. Now, the government is giving away more land to the people.”

Between 1990 and 2020, forests in Southeast Asia were the fastest shrinking globally. Cambodia, once the poster child for conservation with 60% forest cover as of 2000, has seen the greatest losses in the region, losing one quarter of that since.

Cambodian deforestation rates have seen a significant uptick in the past decade, with a March report by Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime finding that it lost 11.7% of forest coverage in protected areas between 2011 and 2018.

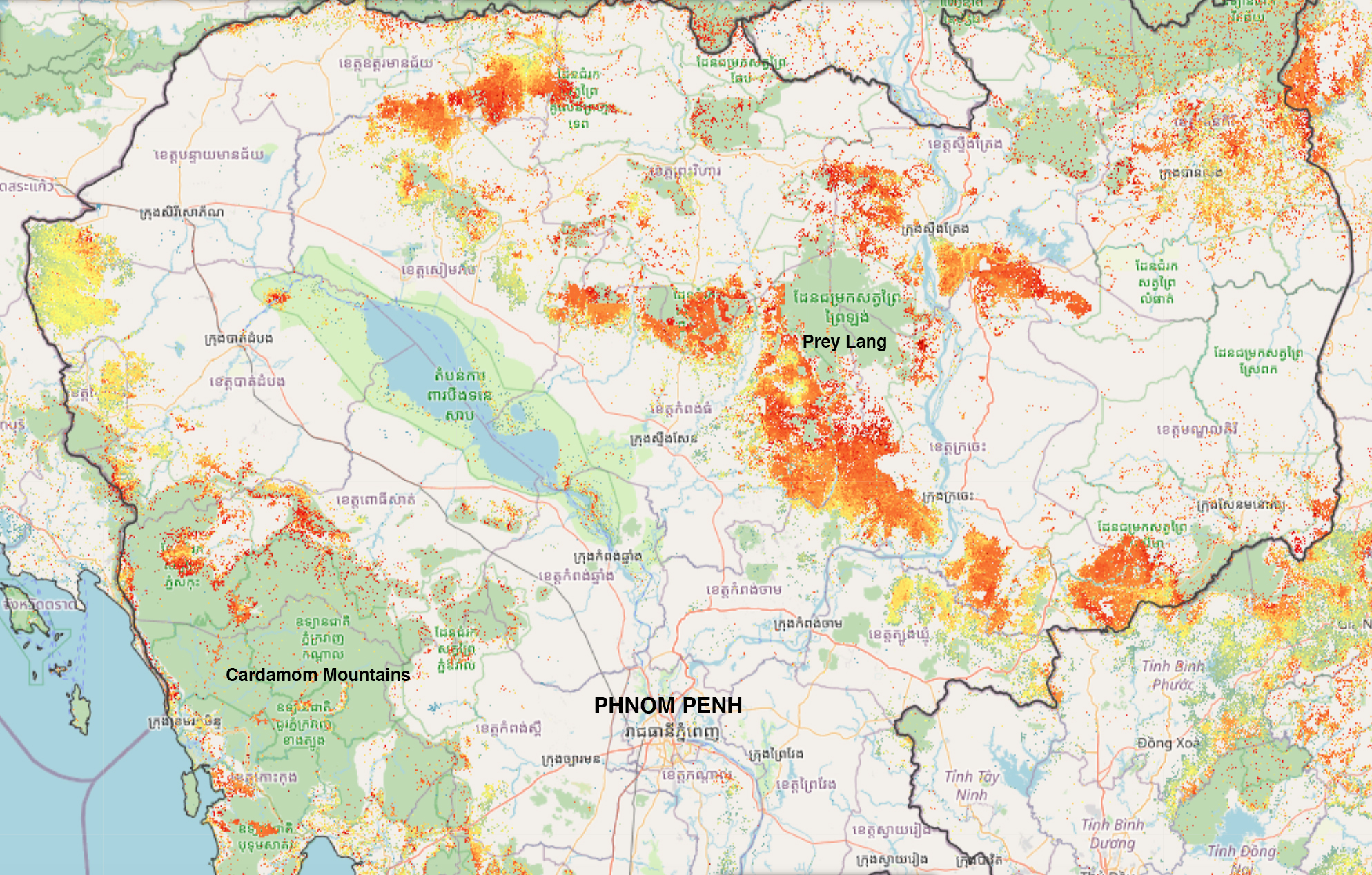

These are facts not lost on an environmental data analyst as he walked a Globe reporter through the various satellite imagery-based trackers employed by researchers around the world today to monitor deforestation. Working close to the issue, he requests anonymity.

One of several tools shown was the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre’s map, which colour codes satellite-detected deforestation by the year they occur.

“If it’s red, the logging is 2020,” he said. Scrolling through the map of Cambodia, an unmissable block of crimson sits at the Kingdom’s heart. “Prey Lang is that sea of red.”

While the forests of the Cardamom Mountains have so far avoided the level of destruction that has befallen Prey Lang, the sanctuary today serves as a cautionary tale for what could be.

Covering some 3,600 km2 across four provinces in north-central Cambodia, in 2016 Prey Lang’s parameters were formalised, its protection status raised and a REDD+ conservation programme established. The UN-led global scheme aims to protect forests through contributions from high carbon-emitting entities looking to offset their footprint.

The year 2016 also saw the USAID embark upon five-year, $21 million conservation programme Greening Prey Lang. However, the rapid deforestation in the area seen since, attributed to high levels of corruption, resulted in the US Embassy in Cambodia announcing an end to their involvement last week.

“Despite USAID’s support … the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary has lost approximately 38,000 hectares of forest, nearly nine percent of its forest cover,” the embassy wrote on June 17.

For conservationists, the March Koh Kong sub-decree represents a potential opening shot in a new deforestation campaign in the area – an ominous sign for future environmental degradation.

Ida Theilade, a conservation scientist and professor at the University of Copenhagen, emphasised to the Globe the ecological impact of breaking the forest into smaller areas split by conceded land, as seems to be the sub-decree’s intent.

“This will have dire implications for biodiversity, including wildlife,” she said. “The suggested ‘donation’ of individual pieces of land in many different places sounds about the most harmful method one could come up with. Fragmentation is the best way to diminish the effectiveness of a protected area and do the most harm to biodiversity and ecosystem function.”

The government frames the move as a poverty alleviation effort, with Ministry of Environment spokesperson Neth Pheaktra telling the Globe they “must carve out land in forest covers, protected areas or wildlife sanctuaries” to give to long-time residents. He added that this is “aimed at improving the people’s livelihoods, securing their food security and preventing them from migrating to find work in other countries”.

When asked for comment on the sub-decree, Wildlife Alliance founder and CEO Suwanna Gauntlett echoed this sentiment.

“Wildlife Alliance very much appreciates the Prime Minister’s poverty alleviation initiative through land allocation. This has largely been implemented through the Ministry of Environment and the local authorities. We have had an important consultative role,” she wrote to the Globe, also pointing to the positive social impact of the group’s REDD+ project.

This disconnect between conservation scientist and conservation NGO on the sub-decree is hard to ignore – and for those unfamiliar with Cambodia’s political context, perhaps even hard to fathom. But one doesn’t need to look far for evidence of the pitfalls of not toeing the line in the world of Cambodian environmentalism.

On June 16, Mother Nature activists Sun Ratha, Ly Chandaravuth and Yim Leanghy were arrested while recording sewage flowing into the Tonle Sap on Phnom Penh’s riverside. The three have since been charged with plotting against the government and insulting the king, and face between five and 10 years in prison.

In May, three other Mother Nature campaigners were also sentenced to between 18 and 20 months in jail for organising a campaign against the ongoing filling-in of Boeung Tamouk, one of Phnom Penh’s last remaining lakes.

The legal warfare being conducted seems an attempt to put the final nail in the coffin for the vocal environmental activist group, long a thorn in the government’s side. Registered as an NGO in 2012, it disbanded under duress from authorities in 2017. Its founder, Alejandro Gonzalez-Davison, was himself expelled from Cambodia in 2015.

“The witch hunt that the increasingly paranoid Hun Sen regime is doing against Mother Nature activists is further evidence of how scared they are of young people in our videos inspiring countless others,” Gonzalez-Davison wrote to the Globe via messaging app Signal. These days he places an auto-delete function on all his messages for security reasons.

If these NGOs are too critical or radical, then they risk being shut out. Is it better to be government-compliant, and keep a seat at the table? I’m not sure. Ethical dilemmas abound

Today, being a member of Mother Nature in Cambodia is akin to being a member of a banned underground political movement.

In Chi Phat, a small ecotourism village located upriver from Roman’s Stung Proat ranger station in the Southern Cardamoms, former Mother Nature activist Dara doesn’t take any chances when speaking with Globe reporters. Wildlife Alliance have a strong presence in the town through their community building work, and he is concerned about being seen talking to the press.

He arranges a rendezvous – a scenic waterfall on the outskirts of town – and drops off a motorcycle for reporters on which to travel to the spot to meet him. Serving a 10 month and 15-day sentence himself in 2015 for his environmental activism, today he struggles to earn a living.

“Now I’m working on a small farm, but it’s difficult to find a job after being in prison,” Dara said, the cascading waterfall behind him.

After speaking, Dara is approached by a Ministry of Environment official who reporters had earlier met patrolling the forest with Wildlife Alliance. The official, at the spot for unknown reasons, asks Dara why he is speaking with journalists.

For Gonzalez-Davison, the concessions made by major NGOs to avoid this same kind of daily harassment has left their conservation activities compromised. He adds that their work is often tantamount to “greenwashing” the government.

“It is now evident that the approach by the international NGOs who have been in Cambodia for around 20 years or so – Wildlife Alliance, Fauna & Flora International, WWF – is simply not efficient when it comes to the conservation of nature,” he said.

Sarah Milne, a senior lecturer at the Crawford School of Public Policy at the Australian National University, told the Globe that Wildlife Alliance’s longevity “does suggest a level of government compliance”.

“International conservation NGOs in Cambodia are all dependent upon their relationship to the government. They operate through government partnerships to manage vast territories,” she told the Globe. Milne’s research examines the politics of natural resource struggles in Cambodia.

“So if these NGOs are too critical or radical, then they risk being shut out. Is it better to be government-compliant, and keep a seat at the table? I’m not sure. Ethical dilemmas abound.”

Whether this uneasy alliance with the government is a necessary evil or a compromise too far, there is evidence for the positive impact that Wildlife Alliance’s work can have at the local level.

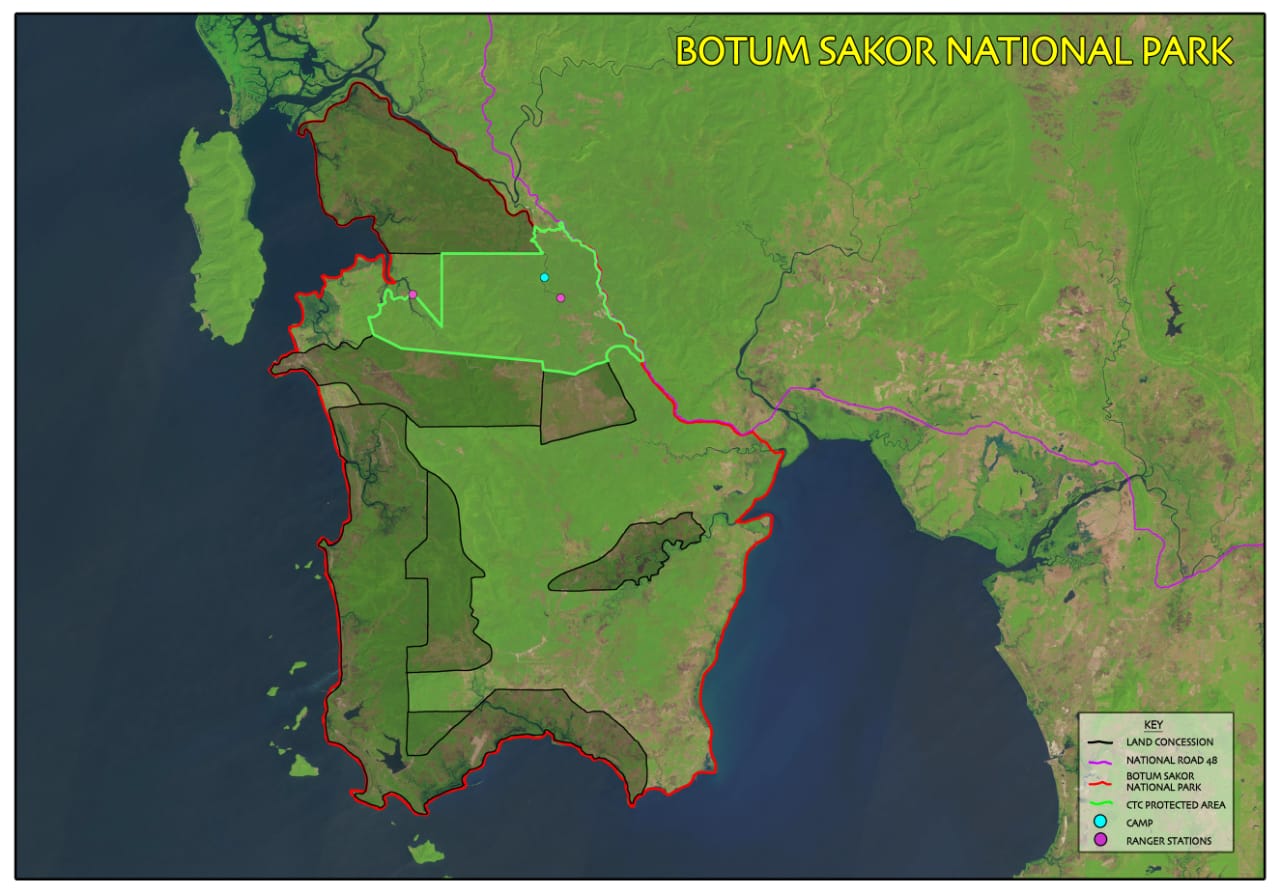

Back in March, when the sub-decree became public knowledge, few were more disconcerted than Allan Michaud. The British wildlife photographer today manages the Cardamom Tented Camp located in Botum Sakor National Park – part of the wider Cardamom mountain range. The National Park is the largest of eight areas earmarked for distribution in the sub-decree, with 30,000 hectares up for grabs.

The camp is only accessible by boat, and so Allan regularly ferries back and forth along the narrow Prek Tachan river, narrating the changing ecological landscape around him that he’s witnessed in his four years at the camp.

“Koh Kong island will be the next big development,” he said confidently, as the boat passes under a newly-constructed bridge, thrown up in the past year as part of growing infrastructure in the area.

Rumours are swirling of a Chinese investment boom on the currently undeveloped island off the southern coast, spearheaded by powerful Cambodian tycoon and politician Ly Yong Phat.

The tented camp eco-tourism project is set among the forest in a natural clearing within a Wildlife Alliance 18,000-hectare tourism concession. A partner to the NGO, profits go towards funding two ranger stations, like Roman’s, in the National Park.

Funded by a philanthropist at its inception in 2017, Allan says that today money has dried up due to the pandemic, with the project surviving on support from the Golden Triangle Asian Elephant Foundation in Thailand. But while cash remains an immediate concern to the camp’s survival, Allan sees the March sub-decree as posing an existential threat to the forest surrounding it.

“We are slowly being surrounded as an island. It’s scary,” he said, holding up a map of Botom Sokor National Park. Like battle lines during war, the map is carved up into distinct entities under the control of different groups.

“For us, and for the rangers trying to protect this area, this recent sub-decree will unfortunately only make that job harder,” he said.

The Wildlife Alliance protected area in which the camp sits is constantly under threat of encroachment by those surrounding it.

To the south there’s a Ly Yong Phat rubber plantation, through which wildlife poachers regularly enter. To the north, a former Green Rich concession that has now been reclaimed by authorities through the decree, something Allan says has also coincided with increased logging and settlements on the land.

To the east, Road 48 – somewhere Allan regards as the new frontline of the conservation effort in the area. It’s here that he’s witnessed an uptick in attempts at land grabbing along its edge in recent months, people capitalising on the deregulated atmosphere the sub-decree has inspired.

All this contributes to a growing sense of unease for Allan, living in a country where protected areas are fluid and their status holds little weight.

“The lines on the map,” he said. “They don’t mean anything.”