The Penang trishaw: survivors of a unique tradition

A series of unique images tracks the important and unique journey of the three-wheeled trishaw carriage, once a vital mode of transport, now a rarer sight on George Town's streets

Decades before the arrival of taxis and public buses, thousands of trishaws shaped Penang’s transportation system. In the 1950’s, these three-wheeled carriages were a common sight and key mode of transport through the state’s capital George Town.

Today, the number of trishaws has dwindled, gradually phased out in favour of cars and motorbikes. But the vehicles have found other innovative ways to embed themselves in the city’s life and culture.

Trishaws were introduced to Penang around 1935. The Hokkien Chinese call them lang-chhia while local Malays call it “beca“, a Malay word derived from Hokkien dialect which means “be-chia” or horse cart. These carts were the daily mode of transportation around Georgetown before taxis, buses, cars, with over 2000 at their peak.

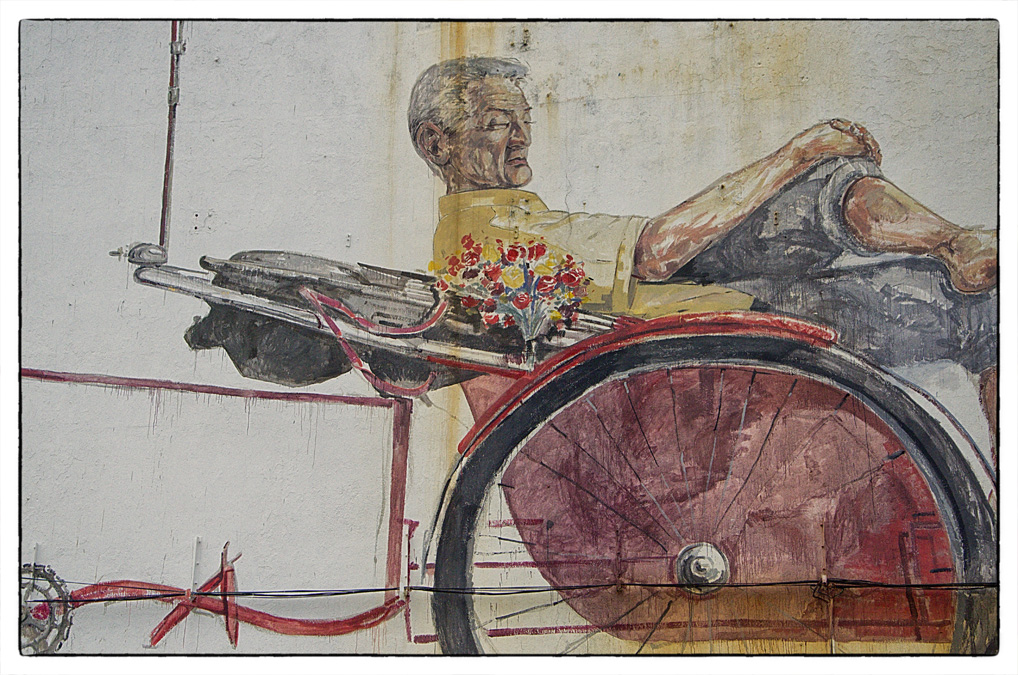

Today, trishaws and their brothers, tricycles, are used to transport food and goods around the island. They have both also been immortalised in the city’s internationally renowned street art that Ernest Zakarevich, young Lithuanian artist introduced in 2011. Since, Street Art in Penang has become one of the main tourist attractions.

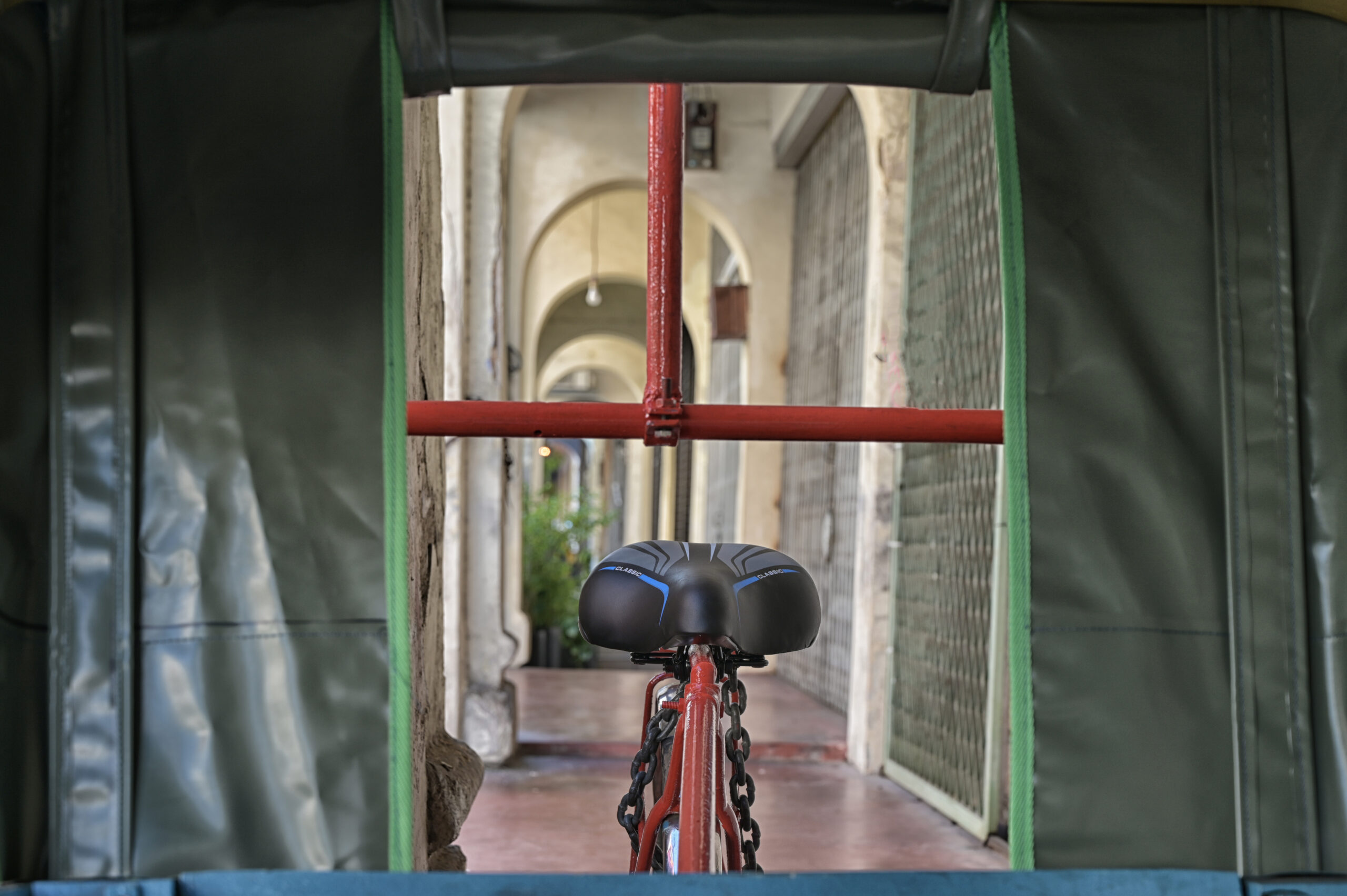

Many old unused trishaws are also used as display, such as the famous trishaw at the Cheong Fatt Tze – The Blue Mansion.

The city’s vital tourism sector, which supports these attractions, has also provided a steady source of passengers for today’s trishaw drivers. Tourism has long been an integral part of George Town’s economic infrastructure: the city was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2008, increasing its profile as an attractive destination for domestic and international visitors. Hotel occupancy surged to 70% the first weekend interstate travel opened in October 2021 and flights and passenger numbers have risen since Malaysian borders reopened in April.

For tourists who are unaccustomed to the tropical heat, walking around Georgetown can be tiresome. Trishaw riders know all the main hotels and often arrange tours that start at the passenger’s accommodation and wind through the city’s main heritage sites. At night, the city lights up with hordes of tricked-out trishaws taking back visitors and the memories of travel from a bygone era.

For many tourists, it is a way to see the city from a different perspective. Mrs. Ines, a visitor from Quebec, noted that she enjoyed riding in trishaws because they provided a different point of view and helped perpetuate an old tradition.

But it also highlights the hardship the drivers experience.

Most riders are renting their trishaws on a weekly or monthly basis from owners. The Covid-19 pandemic hit business hard as lockdowns and travel restrictions dried up the stream of tourism to the city. Several drivers have been sleeping in their trishaws after losing their income and their house during the pandemic and some cannot afford full meals every day.

“I am looking forward to the return of “Mat Salleh” (white people) and local tourists to Penang,” said Mr. Ibrahim, who has been a trishaw driver for 18 years.

At number 19 of Jalan Pintal Tali in George Town, owner Choo Yew Choon opens his shop every morning and hopes that a new day will bring new trishaw orders. Throughout 2022, he has only received two orders for new trishaws, one commissioned by a Western expat living on the Island. He maintains his income through repairs for the existing trishaws, tricycles and bicycles going around Penang Heritage area.

It takes Choo approximately 20-30 days to build a trishaw from scratch to delivery. He sells the new trishaws at $1,553.14 (7000 ringgit) these days. His son lives in Bangkok and has no intention to perpetuate the family tradition.

Some Heritage organisations Penang World Heritage Incorporated are working towards supporting the trishaw riders, but only those who are of Malay ethnicity, according to Mr. Stewart, a Chinese trishaw driver.

“They can receive up to 200 ringgit ($44.37) per month, we don’t even though we are the original ones,” he said.

Private organisations, such as Malaysian bank CIMB, have stepped in with initiatives such as coupons for clients which drivers could redeem for cash at the bank. However, the brief scheme was just implemented for a few months and it came to an end recently.

“So times are still tough,” Mr. Stewart said.

A younger generation of Malay riders are modernising the trishaw experience by decking their vehicles with fluorescent lights and accompanying their rides with loud music. They provide a different sort of ride, focused on entertainment over the history that their older counterparts are working to preserve.

Very few last elderly residents of Georgetown are still using trishaws as their local mode of transportation. One of them is 79-year-old Mrs Tan. When she was a young girl, she was sent to school by trishaw daily. Today, she takes the trishaw to visit her sister on the other side of the Georgetown heritage site. It transports her back in time to the more peaceful, carefree days of her childhood.

Photos by Philippe Durant. Text by Amanda Oon.