August 2015

I wasn’t looking for a new job, and certainly not a full-time one. But that was before I received an email from my friend Yuko, a fellow expat. She told me that the state-run newspaper, The Global New Light of Myanmar, was looking to hire its first foreign editor.

Her friend Sean had been seconded there for six months by his employer in Japan, Kyodo News, as part of a two-year partnership that aimed to improve the look and feel of Myanmar’s state-run newspaper. The partnership was coming to an end and Sean was returning to Tokyo, so The Global New Light of Myanmar was looking to hire a foreign editor to take his place. She thought I might be interested and asked if I would like to contact Sean about a possible job interview.

At first I thought Yuko’s email was a joke. I was aware that the newspaper had made some changes in line with Myanmar’s reform process, but it was hard to believe that those changes would extend to hiring a permanent foreign editor. It seemed too insular an enterprise.

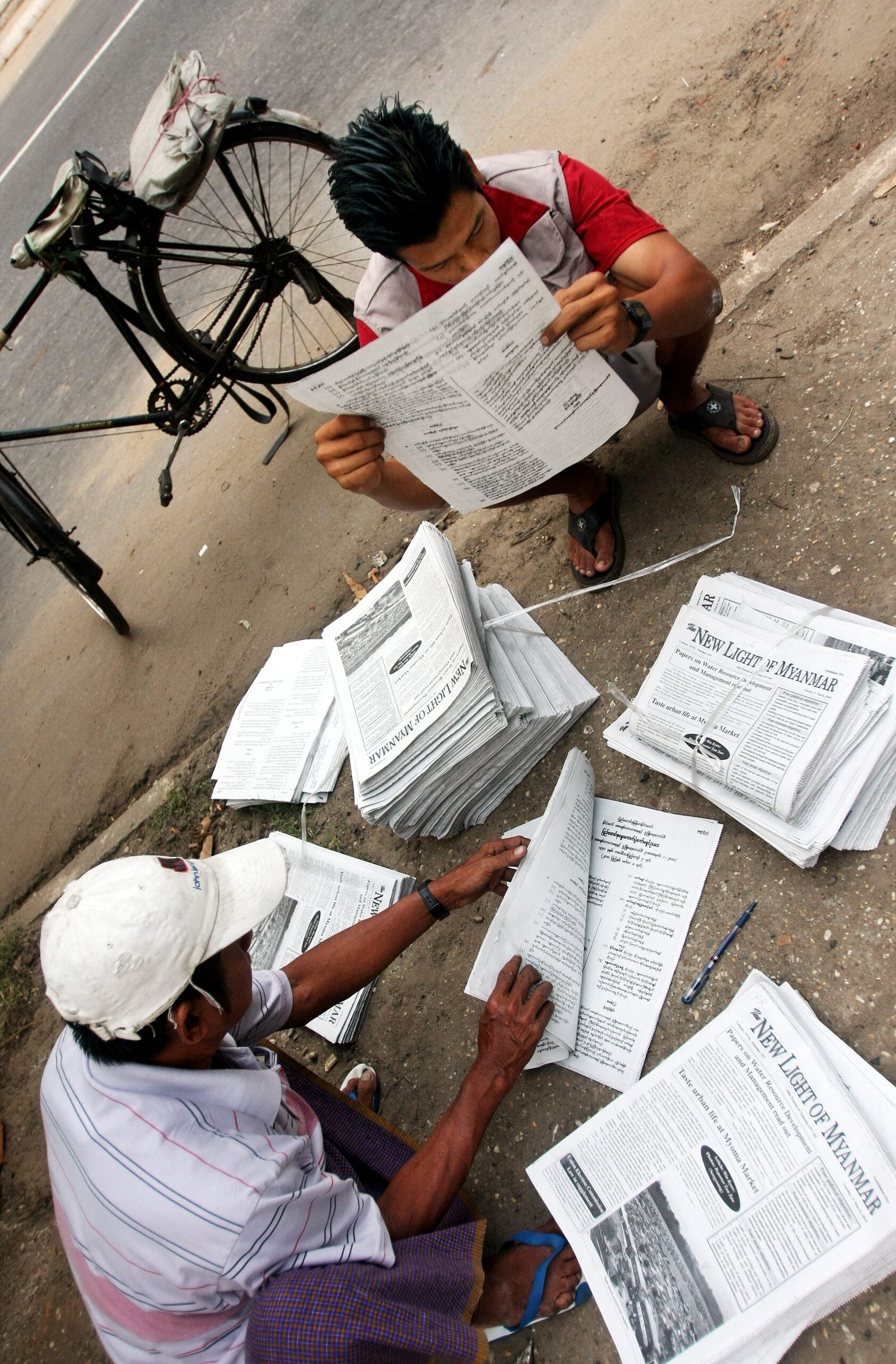

For fifty years, the regime had used The New Light, as it was often called, as its propaganda tool. Most of the articles covered select activities by the regime and its cronies, such as cutting the ribbon at a new monastery, and everything was cast in glowing terms – under the wisdom of junta rule, social ills like poverty and crime did not exist. International news was censored and there were also fillers of dubious news value – I once read an article about a refrigerator being found in a paddock.

In recent times, The New Light had been attempting to revamp its image, as the country itself was. The partnership with Kyodo News had seen the newspaper go from smudgy black and white to colour, and the word ‘Global’ was inserted into its already long title – a change that was presumably meant to convey a more international outlook for the former hermit nation. But The New Light was still very much the mouthpiece of the quasi-civilian ruling party, whom it never, ever criticised. And it still carried some laughably dull news stories.

Why on earth, then, would I want to work there? I wasn’t sure that I did. I was curious, certainly, but also apprehensive about becoming an employee of the powerful Ministry of Information, which was responsible for Myanmar’s state-run media. Virtually all of the members of Myanmar’s reformist government had military backgrounds, including the information minister, U Ye Htut. The same people who had overseen one of the world’s most brutal dictatorships would effectively be my employers. What would the consequences be if I made a mistake?

Despite my misgivings, curiosity won out. Working at The New Light was the closest I’d ever get to a real-life version of George Orwell’s depiction of newspeak and the Ministry of Truth in Nineteen Eighty-Four. Propaganda had always fascinated me, and it sounded as though there was an opportunity to make positive changes at the newspaper, in order to reflect a more democratic Myanmar.

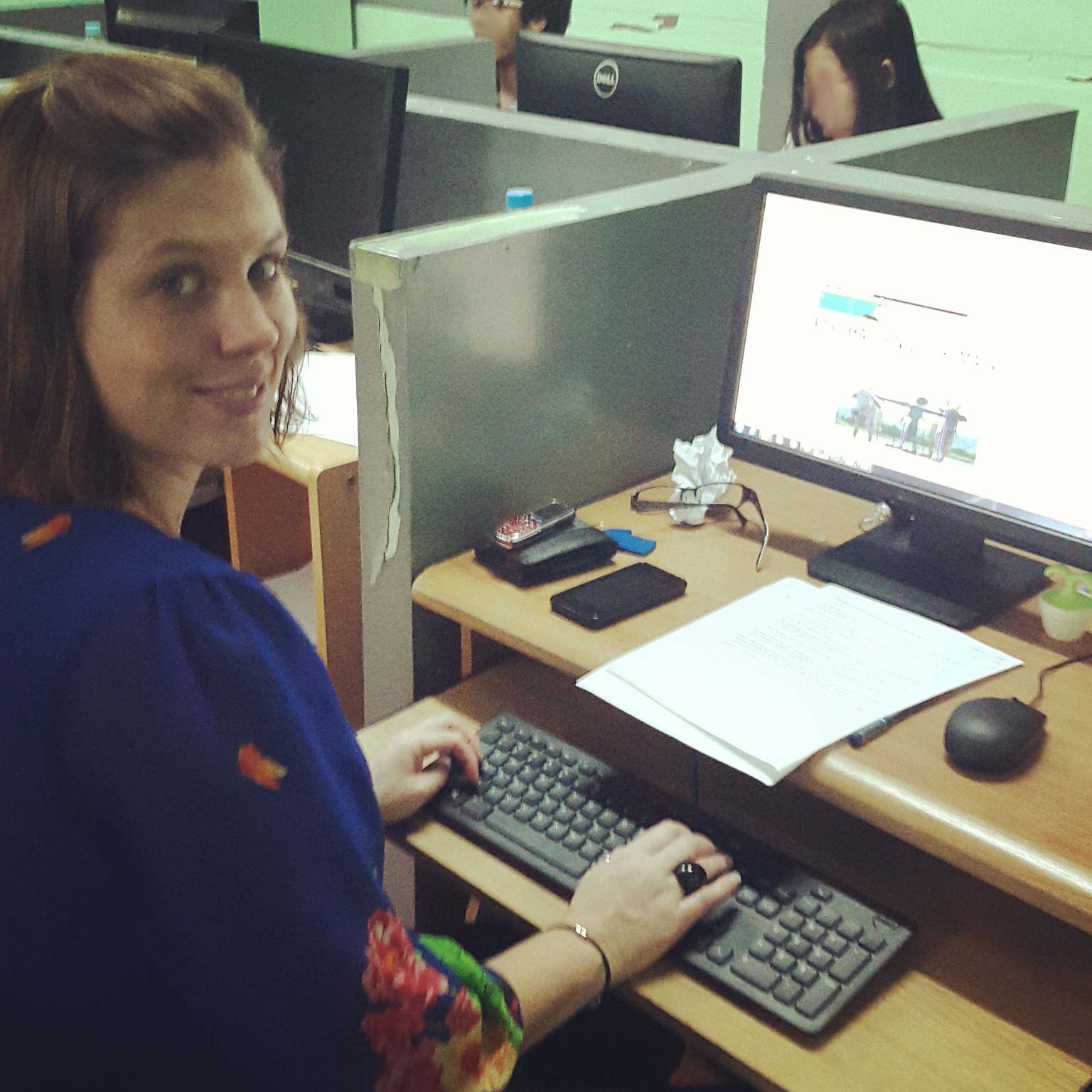

It looked like a typical newsroom, with reporters and translators huddled over their screens and dusty stacks of past editions lining the back wall. A TV played the rolling news on MITV, a state-run channel. It was obvious, though, that the government was miserly in its funding of the enterprise. We worked on uncomfortable plastic chairs and some of the desks and computers looked about a hundred years old.

When the betel-chewing Burmese news editor Wallace introduced me to the chief reporter, Ko Aye Min Soe, the first thing that came out of his mouth was, “We must improve the paper.” Hearing this was encouraging, because it suggested that the team was keen to embrace further changes.

Ko Aye Min Soe looked to be about thirty and he had an unmistakable twinkle in his eye, although he also looked weary. He wore a faded, short-sleeved shirt tucked into a longyi. He told me that the newspaper’s managers wanted The New Light to emulate The Straits Times in Singapore. In other words – censored and pro-ruling party, but of respectable quality.

I returned to my desk feeling excited about the unusual opportunity I’d been given. But when I read the story that was sitting in my inbox waiting to be sub-edited, I suddenly felt overwhelmed. There was so much wrong with it that I didn’t know where to start.

Low production of maize in some areas of Tatkon

TATKON—A lack of rain in some areas of Tatkon Township in Nay Pyi Taw Council Area has decreased maize production this year, according to a maize farmer in Naungthikha Anawyahta ward. But the farm hands processing maize from the ‘888-species’ corn crop are in much supply and cheap, as the workers are keen to skin the corn husks which are much in demand to be used as filters for Myanmar cheroots. The current price of a basket (33.33 kg) of maize is K10,000 which is good, said the maize farmer, who cultivated 10 acres of maize. He added that maize brokers come to buy right to his house.

It was one thing to say that I was going to help The New Light become a better newspaper: making it happen would be another. I tried not to despair. Instead, I went over to Wallace’s desk. Every shift, he sent me about ten news stories to sub-edit after they had been translated into English. The stories from our reporters outside Yangon mostly arrived by fax.

He told me that the newspaper’s managers wanted The New Light to emulate The Straits Times in Singapore. In other words – censored and pro-ruling party, but of respectable quality

“Hey, Wallace,” I began. “I don’t think we should run the story about maize. It has no news value.”

“Alright,” he said, not sounding thrilled. “I’ll give you another one.”

There was no question that the next story Wallace sent me was newsworthy. Police had intercepted a baby elephant and two adult females being smuggled from the far northern state of Kachin. The problem was that vital bits of information were missing, and certain aspects of the story didn’t make sense. Were the elephants being smuggled as part of the ivory trade in China? But if so, why were they heading to Bago, which was in the opposite direction? Was it really possible to fit three elephants onto a single truck, as the reporter claimed? What penalty were the smugglers facing? What would happen to the elephants now?

I went back over to Wallace’s desk. He looked up from his screen and gave me a watery smile.

“Sorry to bother you again, Wallace. Can I get the translator to call the reporter and ask him a few questions about the elephant smuggling story?”

“We don’t have phone numbers for our regional reporters,” he replied.

“Could we send him an email then?”

“They don’t use email.”

“Ah, okay,” I said. “I guess I’ll work with what I’ve got.”

“Very good,” said Wallace. “I’m just about to send you three more stories. I need them all back by 8 p.m.”

Unfortunately, the first story I opened read like a shopping list. It contained such an excruciating level of detail about the contents of a donation to monks that it would make a reader’s eyes glaze over.

After thinking hard about what to do, I decided then and there to be pragmatic. The newspaper’s pages had to be filled every day and our time to work on each edition was limited. If the best I could do was to improve the grammar in certain stories, so be it – for now. I made a note to discuss the ‘five W’s’ of reporting during our next newsroom meeting, because it was already clear that the who, what, where, when and why were often missing from our stories. Decades of censorship and self censorship had produced a misplaced focus on the mundane.

I also didn’t want to drive Wallace completely nuts by taking issue with every article he sent me. He was already exhausted. He worked twelve-hour shifts seven days a week and got just three days off a year. I wasn’t sure whether he even had any interest in journalism, as at no point had he mentioned wanting to work at a newspaper. He’d proudly told me about his years as a captain in the military, back when he was still a young man. While fighting against insurgent groups in the jungle, he’d contracted cerebral malaria and nearly died. When he recovered, he was transferred to The New Light. That was fifteen years earlier.

During my second week in the job, I walked into the newsroom and saw Wallace look at me with a face full of worry lines.

“Take a seat,” he said, extending a sinewy arm towards the empty chair on the other side of his desk.

I gulped and sat.

“I got a phone call from the information minister this morning about a story you edited yesterday. You inserted the name of the interfaith marriage bill into the article. He was very angry that you did that.”

I knew that the proposed law was contentious because it would make it difficult for Buddhist women to marry men from different religions. I had simply assumed that the reporter had missed out that detail, and that the obvious thing to do was include it. Wrong.

“I’m really sorry, Wallace,” I said. “I’ll check with you before adding in something that could be controversial.”

“Thank you,” he said, and stood up to go check the fax machine.

The exchange rattled me, so when Wallace emailed me half an hour later with a request to edit a public message from President Thein Sein, I nervously wondered whether I would get myself into hot water again.

I opened the Word document with a sense of trepidation. To my dismay, I saw that it was riddled with grammatical errors. I wanted the president to sound – well – presidential, but I was worried that I might inadvertently change the meaning of his words, which I figured someone else had drafted on his behalf. I spent a long time deliberating every correction. To my relief, there was no call from the minister the following day, and Wallace often gave me the job of polishing the president’s words.

I was thrilled when some of our readers noticed the improvements I’d helped bring about at The New Light. A foreign correspondent in Yangon took a photo of a page and shared it on social media, praising the newspaper for being more balanced in its coverage of the upcoming elections. That felt great.

The stories that came from the military-owned news agency, Myawady Daily, were always problematic

But I wasn’t proud of everything I did. Sub-editing propaganda made me feel pretty terrible. The stories that came from the military-owned news agency, Myawady Daily, were always problematic. The news agency had been established in 2011, right after the quasi-civilian government was sworn in. It was part of the military’s surprisingly extensive media portfolio and published by the distinctly Orwellian-sounding Directorate of Public Relations and Psychological Warfare.

The stories we received were completely one-sided, and possibly untrue. For example, one day Wallace asked me to edit a story that claimed that the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) had breached the newly created ceasefire agreement and was ‘harassing locals’. The Burmese military was therefore justified in attacking the KIA camp with ‘air and artillery power’. Like all the stories from Myawady Daily, only the fatalities on the military’s side were included.

I hated editing these kinds of stories, but I never said anything to Wallace. It wasn’t for me to pick and choose the stories I sub-edited, and there was no question that we would continue to run them. I’m not sure whether Wallace suspected my reluctance, but he would sometimes inform me in an email whether a story was a ‘must’ story – and it was often the ones I felt worst about.

As I got to know my colleagues better over time, I asked them how they felt about facilitating propaganda. Contrary to what outsiders assumed, none of them (other than Wallace) had supported the military regime. It was simply a job and a way of being able to use English in a professional context – and such opportunities were still in short supply.

My colleagues were kind and thoughtful people. One wrote poetry in his spare time, while another was working on a novel. There was also a young fitness fanatic. A translator, who I’ll call U Nyan Aung, was a former political prisoner. He’d spent eight years in prison after taking part in a pro-communist rally when he was twenty-three.

“At school I’d wanted to be a writer,” U Nyan Aung told me one night as we smoked a cigarette in the dimly lit outdoor space. “But when I came out of prison, I had no skills. I hadn’t graduated from university and I was too old to return. I was always opposed to military rule and I didn’t want to work for the regime – no one did. But I got the job here very easily after sitting an English-language test.”

Another colleague who had been with the newspaper for fifteen years said that The New Light was the only source of English-language teaching material that tutors could afford to buy. So he saw his work not so much as aiding propaganda but as a way of helping his fellow Burmese to learn English.

“I always said to my teacher friends: ‘Ignore the message and focus on the language’,” he explained.

I took my colleague’s advice when I had to sub-edit propaganda, although it always sat uneasily with me.

Sometimes changes were made to the newspaper’s contents that mystified me. Stories that Wallace had sent me to edit didn’t appear in the newspaper, or I’d find that paragraphs had been removed. When we lost an excellent story filed by one of our most experienced reporters, Ye Myint, I was frustrated. He had got some great quotes from primary sources about working conditions in Myanmar’s garment factories, which were being used by the likes of Adidas.

We had strong photos and Oxfam had just published a new report on the issue. We’d made it the lead story on the front page and I’d given it the headline Not a Pretty Picture, which I felt was safe because it was an understatement.

To my chagrin, I saw that the entire story had disappeared and in its place was an article that was six days old – an eternity in news – about UNESCO giving Inle Lake World Heritage List status. Why would our reporters bother taking my suggestions onboard to write better stories if their efforts were in vain? I went over to Wallace’s desk to try to find out what had happened.

“Hi there, Wallace. I noticed that Ye Myint’s story on the garment industry was spiked. I thought you’d said it was a great story?”

“Ah yes, that one. He told me not to run it.”

“Sorry. Who is he?”

Wallace mumbled something indiscernible about the Ministry of Information and began shuffling the documents in his in-tray. I didn’t think it was the minister himself who had given the order, because he surely wouldn’t have had the time – and when he’d called Wallace enraged about me mentioning the interfaith marriage bill, it was after the newspaper had been printed.

“Who was it who told you not to run it?”

Wallace averted my gaze and kept on chewing betel.

“Wallace? Is there a man in the clouds?”

Wallace’s eyes lit up. “Yes,” he said, with a chortle. “You could say that: a man in the clouds. He knows everything. He tells me what to do.”

The nickname spread in the newsroom. Together we tried not to anger the man in the clouds. It was almost like a game, where winning meant keeping all of that day’s content. However, trying to predict what would fall foul of him was impossible. I think that was partly because the newspaper was in the midst of change, and it was hard to know how far the changes extended.

One night, Ko Aye Min Soe and I stood around a designer’s screen, deliberating over which photo to use for a story about a major drugs haul. I wanted to use the one we had of a middle-aged woman who had discovered the drugs in a creek while fishing for recyclable plastics that she could sell.

“We won’t be allowed to use that photo – the creek is filled with rubbish,” cautioned our young designer, Nyi Zaw Moe. “How about the shot of the men in front of the drugs stash?” he said, referring to an image of two scrawny young men in handcuffs. They were standing in front of a table laid out with blocks of methamphetamines. But we went with the shot of the woman beside the littered creek, and the photo made its way into the newspaper. This would have been unthinkable just a couple of years earlier.

I often wondered what the man in the clouds thought of my work at The New Light – assuming he knew I was there. Or perhaps it had been his idea in the first place to hire a foreign editor. Was he happy with the changes I was making at the newspaper, or was I pushing things too far? Would he have me sacked if I made too many errors of judgement?

It was by far the strangest work relationship I ever had.

This is an adapted version of Chapter 21 from Jessica Mudditt’s book Our Home in Myanmar, available on Amazon as a paperback, ebook and audiobook.