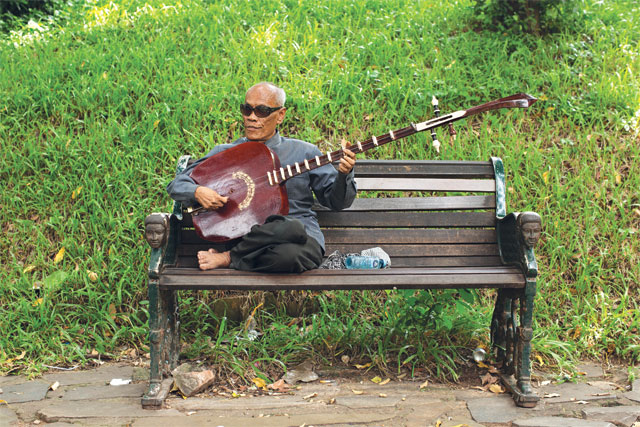

Perched on a bench in his distinctive way, legs curled beneath his body, Kong Nay’s hauntingly beautiful, raspy voice carries on the light breeze swirling around Wat Phnom. With an audience of some 60 admirers, the master chapei player treats his crowd to a few songs. One has the spectators giggling from start to finish. Another is so captivating that blinking suddenly seems unnecessary.

Sporting his signature dark shades and with a bright smile spread across his face, Kong Nay – who has been dubbed the Ray Charles of Cambodia – takes a break from strumming the two strings of his long-necked, lute-like instrument to share a little about his life and music.

Contracting smallpox as a young child, Kong Nay was blind by the time he was four years old. It wasn’t until he was seven, however, that he realised the extent of his ailment and how it would affect his future.

“I became a musician because of my blindness,” he says. “I cannot read or write so I thought that learning an instrument would be a good way for me to make a living. When I was 13, my father bought me my first chapei and my uncle taught me how to play.”

Listening to the flawless pulse of Kong Nay’s performance, it’s hard to believe such perfection could be achieved without the ability to see.

“To learn how to play, I would first ask my teachers to play the songs for me. I would then listen carefully to the rhythms and intonations of the music and try to replicate that,” he says.

After two years of training, Kong Nay put on his first performance in his village at the age of 15. Today, aged 68, he has undoubtedly taken his place among the legends of Cambodian music.

The chapei became very popular among Cambodians for its ability to tell stories. The music educates people in how to live a good life and be a good person.

All-star jam sessions, international tours and praise from industry bigwigs have all dotted Kong Nay’s career, but it was a performance in Sihanoukville that remains his fondest memory.

“When I was 17 years old I was invited to play at a temple in Sihanoukville,” he says. “I was so excited as I was so young and there were so many people there to watch me. The song I played was a kind of parting song. It was very meaningful for me. I will never forget that day.”

Kong Nay’s life has certainly not been without its perils, though. As an artist, and an often satirical one at that, he was deemed dangerous by the Khmer Rouge, which was responsible for the displacement and murders of about 90% of the Kingdom’s artists and intellectuals. In 1979, Kong Nay and his family almost became victims of the brutal regime as they were marched from their home to the killing fields to be executed. If it weren’t for Vietnamese soldiers rescuing them at the very last minute, Kong Nay’s story would have been abruptly cut short.

Although the Khmer Rouge permanently affected arts and education in Cambodia, Kong Nay is confident that the ancient chapei tradition will live on.

“The chapei became very popular among Cambodians for its ability to tell stories. The music educates people in how to live a good life and be a good person,” he says. “Many young people today like the chapei, and not only that – many also come to me and ask me to teach them how to play.”

There are those, however, that don’t view chapei music quite so positively.

“A small amount of people see the music negatively,” Kong Nay says. “They believe that if they learn to play the chapei then they will become blind like me and Neth Pe – the best chapei singer in Cambodia. But this is simply not true.”