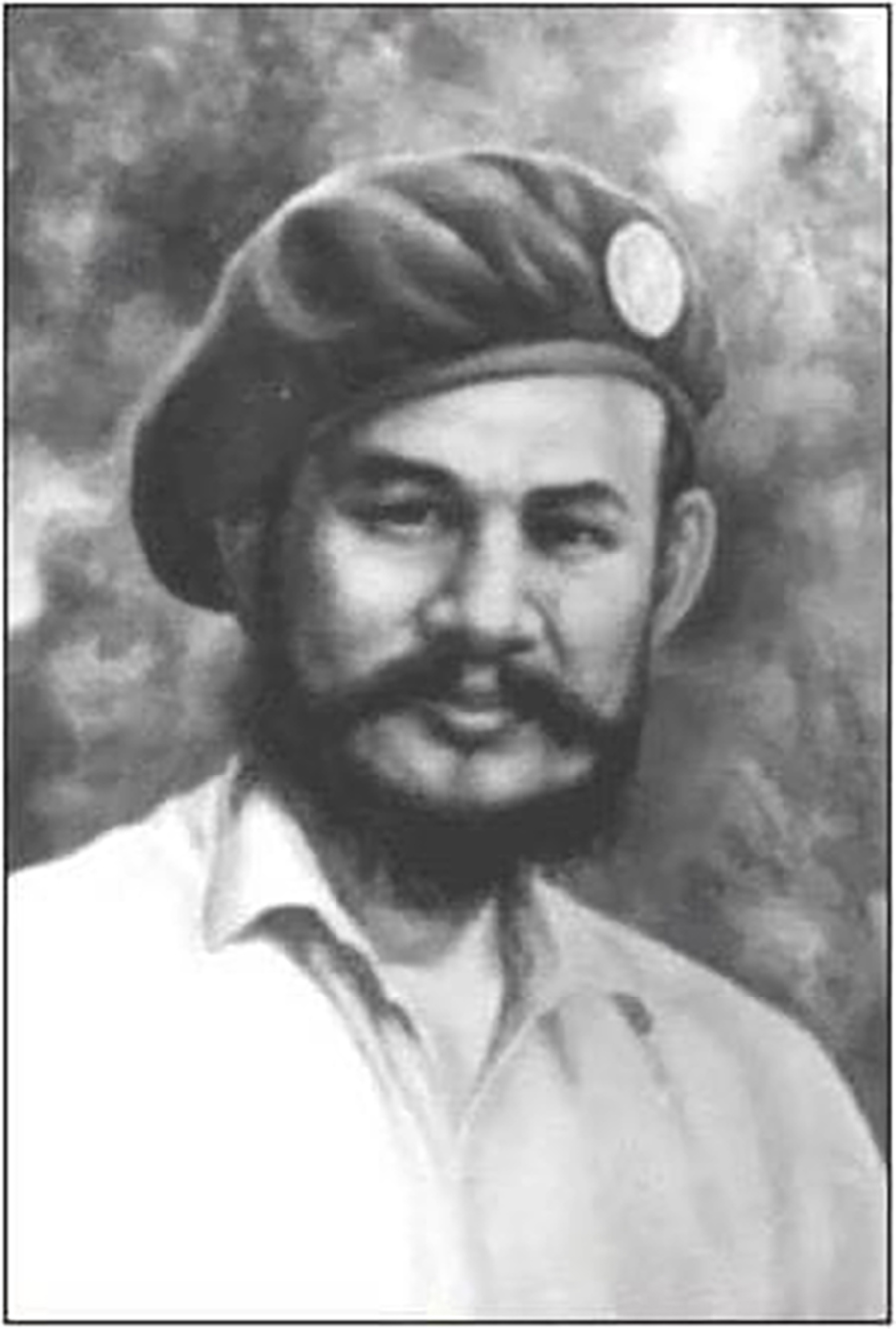

Travel to many parts of Myanmar’s Kayin State today – or Karen, as local people tend to call it – and a particular image will likely stand out. It’s a black and white photograph of a hirsute man wearing a beret and staring intently into the camera, and is not dissimilar to the famed picture of Argentinian revolutionary Che Guevara that adorns t-shirts and bedroom walls around the world.

But in contrast to the South American guerrilla leader, the man in this picture is little known outside – or even inside – Myanmar. He is Saw Ba U Gyi, regarded as the father of the Karen revolution, who led the earliest incarnation of the Karen National Union (KNU) before he was assassinated in an ambush by the Myanmar military, known as the Tatmadaw, near the Thai-Myanmar border on August 12, 1950 – 70 years ago this month.

Often seen below his image are the “four principles of the Karen revolution”, which Saw Ba U Gyi finalised at a KNU congress weeks before his death:

- There shall be no surrender

- The recognition of the Karen State must be complete

- We shall retain our arms

- We shall decide our own political destiny

“Are they still relevant today? The answer, unfortunately, is yes they are,” Paul Sztumpf, Saw Ba U Gyi’s grandson, told the Globe from his home in the UK. “They are the same demands that the Karen people are making in Burma today. Nothing has changed in those dreadful 70 years.”

As an example of just how complicated Myanmar’s series of civil wars are, the KNU – and their armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) – are not currently at war with the Tatmadaw, but nor is there peace in Kayin State.

The KNU has signed bilateral and national ceasefires with the Myanmar government in the last decade, but the Tatmadaw continues to maintain a heavy presence in the state, while displacements, and deaths, continue as a result of ongoing skirmishes between the groups and their proxies.

From Irrawaddy to Cambridge, and back

Saw Ba U Gyi was born into a S’gaw Karen family in a village close to Bassein (now Pathein) in the heart of Burma’s Irrawaddy Delta at the beginning of the 20th century under British colonial rule.

According to Sztumpf, the village Saw Ba U Gyi grew up in was mixed Karen-Bamar, but the two communities rarely mixed.

“My grandfather was a keen sportsman. He was into boxing and football, and while they did play football with Burman [Bamar] teams, that was the extent of their contact,” he said.

Sztumpf was born after his grandfather’s death, but stories were relayed to him by his mother and uncle, both of whom left Burma after the 1942 Japanese invasion during World War II, and spent the rest of their lives abroad. Both are deceased.

“When they spoke about him, the word ‘sport’ always came big in their memories,” Sztumpf said. “There was life around their school, and he would’ve been very keen in organising school activities. He was a lawyer by profession, and would often represent the Karen people, although not exclusively.”

In 1921, Saw Ba U Gyi travelled to the UK, where he spent a year learning Latin before enrolling at Cambridge University’s Magdalene College to study law. He graduated in 1926.

During his studies, Saw Ba U Gyi met Renee Rose Kemp, a seamstress who worked at a Boots pharmaceutical store on London’s Regent Street. The pair married in the summer of 1926, and lived together initially in Highgate, north London, before moving to Edenbridge in Kent in 1927 when their son, Michael Theodore, was born. Thelma Rose, Sztump’s mother, was born two years later.

After Cambridge, Saw Ba U Gyi joined Middle Temple in central London to become a barrister, and was called to the bar in 1929. He returned to Burma with his young family shortly after. Back in Burma, Saw Ba U Gyi established a law firm in central Bassein, but travelled around the country taking cases.

Renee Rose Kemp had initially enjoyed her time in Burma, but eventually started to struggle with life there, especially during the relentless monsoon season, according to Sztumpf.

“She wilted in the airless heat, the swarms of insects at night. She became very ill and suffered from anaemia,” Sztumpf wrote in a biography of his grandfather.

Worse was to befall the family shortly after. In 1942, in the midst of the Southeast Asian theatre of World War II, Japanese forces invaded British Burma, leading to the evacuation of thousands of people, including many Karen who had been aligned with the British. That included Saw Ba U Gyi’s wife and two young children, who travelled first to India, before settling in the United Kingdom. Saw Ba U Gyi stayed behind.

The Japanese invading forces were supported by the newly-formed Burma Independence Army (BIA), a predominantly Bamar group under the leadership of General Aung San, father of State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi. As Japanese and BIA forces advanced into Burma, the latter is reported to have committed a number of atrocities in Karen villages, an example of the hostility between the two groups, which was exacerbated by the widespread – and justified – perception from the Bamar that the British rulers had granted favourable treatment to the Karen, and other minorities.

Saw Ba U Gyi was part of a four-member Karen ‘goodwill’ mission dispatched to London tasked with putting their demands to the British government. However, their trip ended in failure

In one notorious incident, more than 150 Karens were killed by the BIA, including Saw Ba U Gyi’s close friend, Saw Pe Tha and his family. Sztumpf believes this grisly episode contributed strongly to his grandfather’s passionate calls for an independent Karen State.

Joining the revolution

Saw Ba U Gyi initially aimed to achieve this by working closely with the country’s Bamar contingent, and after the Burma Campaign of World War II ended with an Allied victory, he joined Aung San’s pre-independence cabinet. As Burma’s freedom from the British crept ever closer at the end of the war, the calls for the Karen people to be given their own independent state grew ever louder.

But the British showed little interest in such a proposal. They had grown increasingly close with Aung San’s Bamar-majority faction, and the calls from Karen leaders were routinely ignored. In early 1946, Saw Ba U Gyi was part of a four-member Karen “goodwill” mission dispatched to London tasked with putting their demands directly to the British government. However, their trip ended in failure after the British refused to recognise them as official visitors, and the delegation returned to Burma empty-handed.

There was personal heartache too for Saw Ba U Gyi. During his trip to London, he’d said goodbye to his family for the final time, agreeing to divorce his wife and return to Burma alone.

“I think all members of the family had changed, but he was very disappointed in his son, who did not wish to support his father,” Sztumpf said.

In January 1947, Aung San travelled to the United Kingdom to sign the Aung San-Attlee agreement, which paved the way for Burma to be granted her independence within a year. Aung San wouldn’t witness his dream of an independent Burma come true, however, as he was gunned down with members of his cabinet inside Rangoon’s Secretariat Building that July.

Saw Ba U Gyi might have otherwise been in that room, but had resigned in March when it became clear that no progress was being made in the demands for an independent Karen State.

Despite Aung San’s death, independence went ahead on January 4, 1948. With no agreement reached, the Karen leaders decided to take matters into their own hands.

By early 1949, the Karen National Defence Organisation (KNDO) had built up a sizable presence – filled with battle-hardened veterans, as well as weapons from World War II – and controlled several towns across the bottom half of the country.

They also had a heavy presence at Insein, which at the time was a small town nine miles north of the capital, Rangoon. Tension between the KNDO troops and Tatmadaw forces had been building for weeks, and fighting broke out in January 1949, with Karen soldiers quickly seizing control.

Under Saw Ba U Gyi’s leadership, the Karen troops then attempted to take Rangoon, but were thwarted by government soldiers. According to veteran British journalist Martin Smith, Saw Ba U Gyi contacted regiments of the Karen Rifles, stationed elsewhere in the country, to ask for their support to take the capital.

“However, their officers, refusing to believe that the Karen [Tatmadaw] army Chief-of-Staff, Smith Dun, had been replaced by Ne Win, fatally hesitated,” Smith wrote in his book Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity.

This delay allowed government troops the opportunity to replenish their supplies, disarm Karen forces elsewhere in the country, and swing momentum back in their favour. By April, the government was fully in control, increasing the pressure on the Karen forces stationed outside Rangoon.

“The relief in Rangoon was tangible,” Smith wrote. “Each evening office workers would travel nine miles from the capital to take pot-shots at Karen lines.”

On May 22, more than 100 days after the siege had started, it was over. Defeated Karen forces beat a retreat from Insein, with many crossing the Hlaing River and disappearing into the countryside of the Irrawaddy Delta.

But the KNU still had control of much of Lower Burma, as well as allies in the hills to the east. The grizzled veterans of the brutal Burma Campaign of World War II felt confident they could win any war against the Tatmadaw.

Shortly after the defeat at Insein, the KNU held a conference in Toungoo, where a re-organisation of the armed forces was announced, and a new Karen government formed with Saw Ba U Gyi as its prime minister.

In July 1950, a year after Saw Ba U Gyi was installed as the Karen people’s new leader, the KNU held a congress at Papun, the new capital after Toungoo fell to the government. At the event, Saw Ba U Gyi revealed a plan towards gaining independence for the Karen people, as well as what have become known as Saw Ba U Gyi’s “four principles of the Karen revolution”.

A month later, Saw Ba U Gyi and other KNU leaders were travelling near the border with Thailand – possibly en route to meetings with international dignitaries in Bangkok, although this has never been confirmed – when they were caught in a Tatmadaw ambush and killed. After his death, Saw Ba U Gyi’s body was taken to Moulmein (now Mawlamyine) and put on public display, before being thrown into the sea.

After his death, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, the former British Governor of Burma, wrote to The Times about Saw Ba U Gyi and said:

“Saw Ba U Gyi was no terrorist … I, for one, cannot picture him enjoying the miseries and hardships of a rebellion. There must have been some deep impelling reason for his continued resistance … The major tragedy is that Burma is losing her best potential leaders at far too rapid a rate.”

His death dealt a major blow to the Karen movement, but didn’t destroy it entirely. Over the next several decades, the KNU emerged as one of the Tatmadaw’s fiercest enemies, in a series of civil wars throughout Myanmar, many of which continue today.

Ceasefires, but not peace

In 2012, after decades of fighting, the Karen rebels stepped out of the jungle and signed bilateral ceasefires with the government, now headquartered in Myanmar’s new capital Nay Pyi Taw. Three years later, the KNU was the largest and most influential of eight ethnic armed groups to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), a much-hyped accord that the new quasi-civilian government, which had taken power after decades of military rule, hoped would pave the way for peace at last in Myanmar.

But almost five years after it was signed, it has achieved little substantial progress. Although two small groups signed it in early 2018, bringing the total number of signatories to 10, fighting continues in large parts of the country, notably in Rakhine State between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw, as well as among myriad groups in Shan State. Northerly Kachin State has also witnessed intense fighting in recent years.

Even communities in areas under the control of groups that have signed the NCA face an uncertain future. This includes Kayin State, where tensions continue between the KNU and the Tatmadaw, particularly regarding a Myanmar Army road-development project that runs through KNU-controlled territory. Widespread anger towards the Tatmadaw’s build-up in Kayin was heightened in mid-July, when the military admitted that two of its soldiers were responsible for the murder of a Karen woman in Hpapun Township.

In January 2019, I travelled to the Myanmar-Thailand border to attend a ceremony held to commemorate 70 years of the Karen revolution. At a dusty parade ground high up in the Karen hills, thousands of Karen people from across Myanmar and Thailand gathered to watch speeches and military parades, and show their support for the cause.

Among those I met there was Somchai, a Karen pastor who had travelled more than 100 miles from Thailand’s Mae Hong Son province to attend the ceremony. Speaking to me underneath a large image of Saw Ba U Gyi, he said that despite living in Thailand most of his life, he still had Karen family living in Myanmar.

“Many people celebrated the ceasefire when it was signed, but inside Myanmar the lives of Karen people haven’t improved,” he said. “Unless there’s a drastic change in how the government, and the Tatmadaw, view the Karen people, then there won’t be peace. We still haven’t achieved what Saw Ba U Gyi was fighting for.”

Sztumpf expressed pride about his grandfather’s legacy among the Karen people, but admitted that the famed image of him doesn’t tally with the memories of his mother and uncle.

“In the 1920s and 30s, he typically dressed in a smart suit, because that’s what you did in the British colonial world; you dressed in that British way,” he said. “But if he became more like that [in the image], then maybe it happened later, after my mother last saw him, after the civil war started.”

Talking about how he wants his grandfather to be remembered, Sztumpf borrowed the words Archbishop Desmond Tutu used to describe Nelson Mandela.

“He described him as one pebble on the beach, one of thousands. Not an insignificant pebble, I’ll grant you, but a pebble all the same. That is how I would like my grandfather to be remembered.”

The above extract is adapted from Oliver Slow’s forthcoming book After the Junta: Why Myanmar’s military must return to the barracks. More information can be found on his website.