Going off script

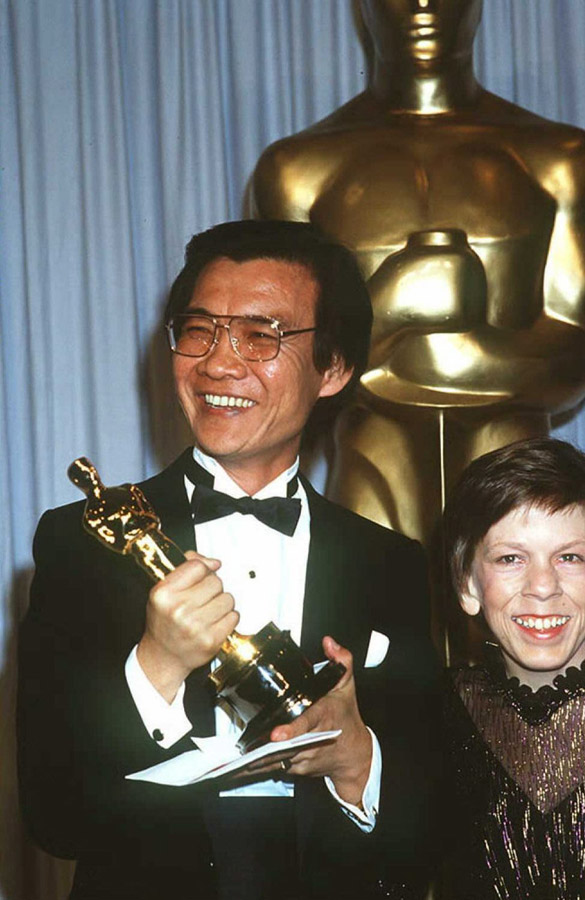

In 1985, Cambodian Haing S Ngor became the first Asian to win an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role in the iconic The Killing Fields. The Globe sat down with the film's screenplay writer Bruce Robinson on the 24th anniversary of Ngor's murder to hear his reflections on the man and the movie

Twenty four years ago, on a rainy February night on the edge of Los Angeles’ Chinatown, Dr Haing S Ngor, a Cambodian physician, parked his Mercedes in a dank, dark, graffiti-daubed alley. Down that end of town, at least, such a car seemed out of place. Sadly, the gunshots that soon followed, were not.

Ngor was found bleeding out on the sidewalk by his neighbours. They knew him better as the Academy Award-winning – yet formerly unknown – star of The Killing Fields.

Ngor’s attackers pulled the trigger when he refused to give up a gold locket that contained a photo of his late wife, Huoy. Unlike her husband, she had not survived the brutal ‘communist utopia’ and forced labour camps of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge Kampuchea.

With $3000 dollars left behind in his wallet, Ngor’s murder was viewed by many as an act of political assassination, instead of an inept mugging. After all, Ngor spent much of his later life campaigning to bring the perpetrators of the Khmer Rouge’s warped logic to justice. To this day, almost a quarter of a century later, case long closed, many still believe Ngor’s murder to be one shrouded in conspiracy.

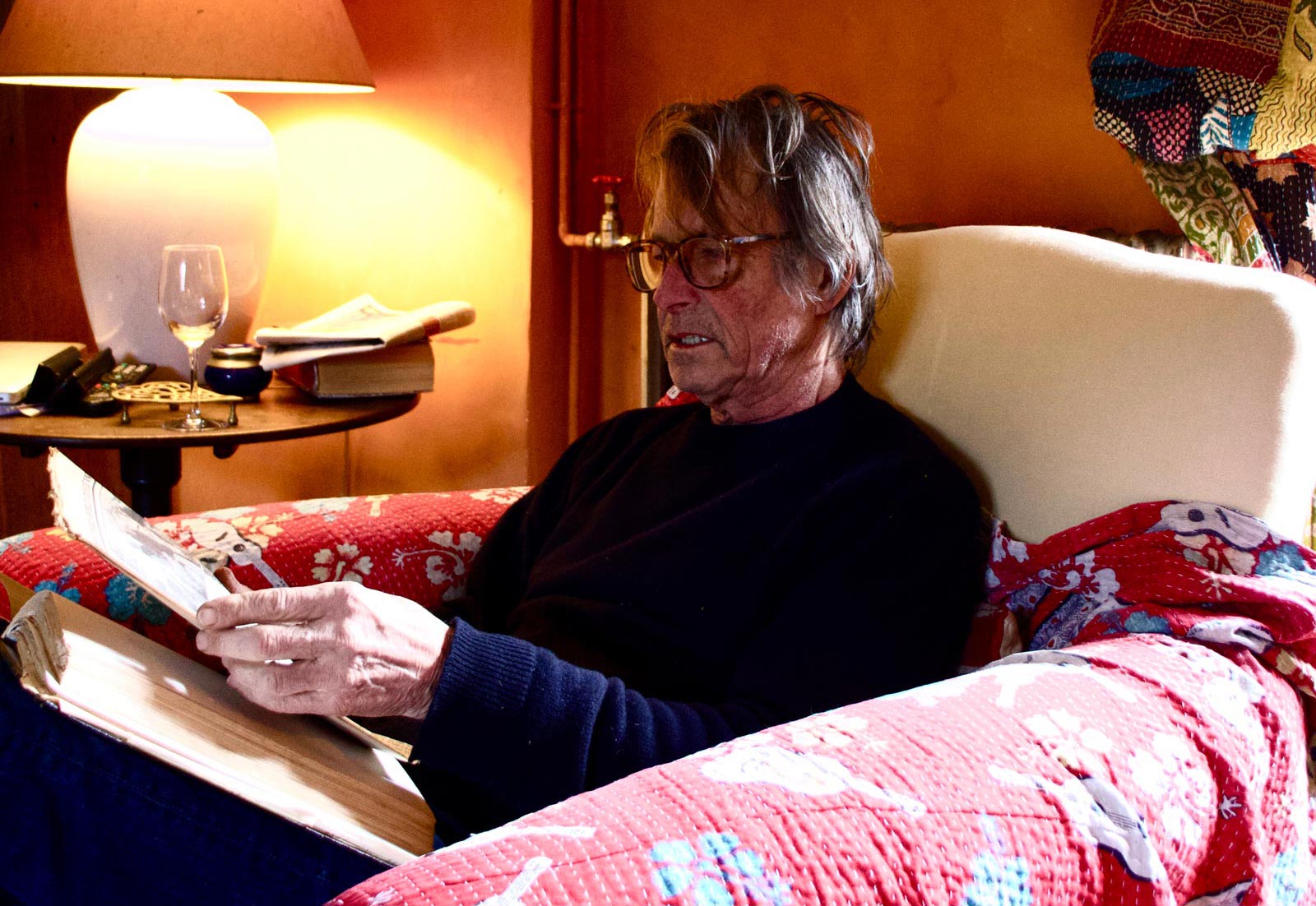

With that in mind, and on an entirely different rainy night in the UK, a battered Peugeot rolled into the driveway of the home of The Killing Fields screenwriter, Bruce Robinson. Besides his scabrous wit (as well as “the finest wines available to humanity“) bringing Bruce to the attention of stoners and scrubbers everywhere via the sublime Withnail & I, it was The Killing Fields that first earned him widespread acclaim in 1984, winning him a BAFTA and introducing the Khmer Rouge’s crimes to many in the West.

As has been the case with much of Bruce’s long, and varied career – through indie hits, and Hollywood disasters (not to mention the exceptional unveiling of Jack the Ripper’s true identity in his Magnum Opus tome, They All Love Jack) fact and fiction curiously intersect.

To mark 24 years since Ngor’s murder, the Globe sat down with Bruce (and his curse soaked tongue) to discuss the making of the movie, Ngor’s remarkable performance as Khmer Rouge survivor Dith Pran that earned him the distinction of being the first person of Asian descent to win Best Supporting Actor, and the film’s legacy, both in Cambodia and across the world.

Bruce, how did the real life story Dith Pran’s capture, and eventual escape from the Khmer Rouge end up in your hands?

A friend of mine was working with the producer David Puttnam who’d had great success with Chariots of fire – and was a big bull in the industry by this point. That friend handed him the novel version of Withnail & I, that I wrote before the screenplay. Puttnam said, “Oh … it’s a book, but I think this guy can write.” At that point, I was basically a stealing-milk-from-the-doorstep writer – I was broke – so I went in to see him, and Puttnam said, “I’ll give you £8,000 [$10,300 today] to write a script a year”. From where I was sitting, it was like a fucking angel had come down.

Well, as a writer, that sounds like the kind of movie-land magic that doesn’t happen anymore. It sounds like a dreamlike situation?

You’re right. I mean, it certainly was dreamlike even back then. Anyway, none of those scripts got made, but one day I got a letter through the post, and in it was Sydney Schanberg’s New York Times article [‘The Life & Death Of Dith Pran’, on which the film is based] Puttnam said: “What do you think about this? Do you want to write it?” So, I read the story, and thought “Fuck, this is great”. I subsequently found out that the studio involved were making it into a big picture. They wanted one of my screenwriting heroes, William Goldman, to do it, but Puttnam – God bless him – stood up for me to write this thing. Which was amazing because it was kind of a hot property at the time.

It’s not a cheap film either, the budget was pretty big, which makes it kind of incredible that it was your first ever produced screenplay.

But that’s the weirdness, though, isn’t it? Of this industry. You can be a waiter in a restaurant one day, and a huge star tomorrow. It can literally change overnight. When The Killing Fields came out I went from getting £3,000 a script to a quarter of a million.

We crossed the rickety bridge into Cambodia. On the other side there was this little Khmer kid sitting there holding a Kalashnikov, wearing a red scarf [a Krama as worn by Rouge soldiers] I’m thinking, “Fuck me, this kid could put me in the ditch right now”

Rumour has it that, for a time, you were the highest-paid screenwriter in the world?

For a time, I may have been. If I was, I didn’t notice it because it was all being nicked by the accountant. (Laughs) I mean, I’m not into money. As long as I’ve got enough to live on; I’m not a money person.

How much did you know about Cambodia before you started researching? How much of what the the Khmer Rouge had done were you aware of?

Absolutely nothing. I was like your average American looking at a map, saying “Is this En-ger-land?” whilst pointing at fucking Iraq. I knew nothing, but I got hooked on Cambodia very quickly. With a subject like that, you can’t fake it, you know? I certainly couldn’t. I remember early on in the writing of it, I was in the back of a black cab in London, and the English driver said something like, “But they don’t feel it like we do, do they?” which is just crazy, but I think that’s kind of how the West feels about whatever awful things are happening elsewhere. So that idea informed the writing quite a bit.

Presumably you went to Cambodia as part of your research?

I did, yes, but I was there for about 20 minutes (laughs) I went to Thailand, where they eventually filmed most of the movie. The one thing I did know about Cambodia was that you could get hold of good, high-quality amphetamines without a prescription. So I went into this pharmacy opposite the hotel, and I said to the girl behind the counter, “I’ve just flown in from England. I’ve got a very important business meeting, and I’m really tired, jet lagged etc. Do you have any powerful ‘vitamins’?”

She took one look at me, and said, “You don’t need vitamins – you want speeeeed! Take this and you’ll be good all night.” And It was this fabulous fucking stuff. Basically methamphetamine in pill form, so it was kind of semi-safe. Anyway, I went back to the hotel and took half of one of them, and it was fucking heavenly. So all the time I was in Thailand, “researching”, I was high as a kite.

(Laughing) But did you ever get to Cambodia?

Sorry, yes, I did! I was up north somewhere, in Thailand, in the mountains, and this guide that was with me pointed over a ravine that had a kind of rope bridge across it, Tarzan style. “Thailand over here” He said, “Cambodia over there!” and that was that. We crossed the rickety bridge into Cambodia. On the other side there was this little Khmer kid sitting there holding a Kalashnikov, wearing a red scarf [a Krama as worn by Khmer Rouge soldiers] I’m thinking, “Fuck me, this kid could put me in the ditch right now” you know? And I’m a total coward. I mean, as far as I’m concerned it’s a film.

And around that time, in the early 80s, Pol Pot and his allies would still have been exiled in the jungle on the Thai border, right?

Exactly! So the after effects of it all were still in motion, really, even then. The other thing I remember, too, on that same trip to Cambodia, was this place that had a sort of huge wet, flooded pit full of crocodiles. I don’t know what they were there for, handbags or something. Anyway, one of the crocodiles swished its tail around, and sprayed my entire body with this filthy, green silt water. And thereafter, I was convinced I had typhoid, and cholera and polio and every other fucking thing. So I think that was the day I decided “I’m out of here.”

After that, I basically read everything I could about the Khmer Rouge, and Cambodia. I talked to a lot of people who had been there at the time, including John Swain, and the pack of journalists, who are characters in the film. Of course, I spoke to Sydney Schanberg and Dith Pran.

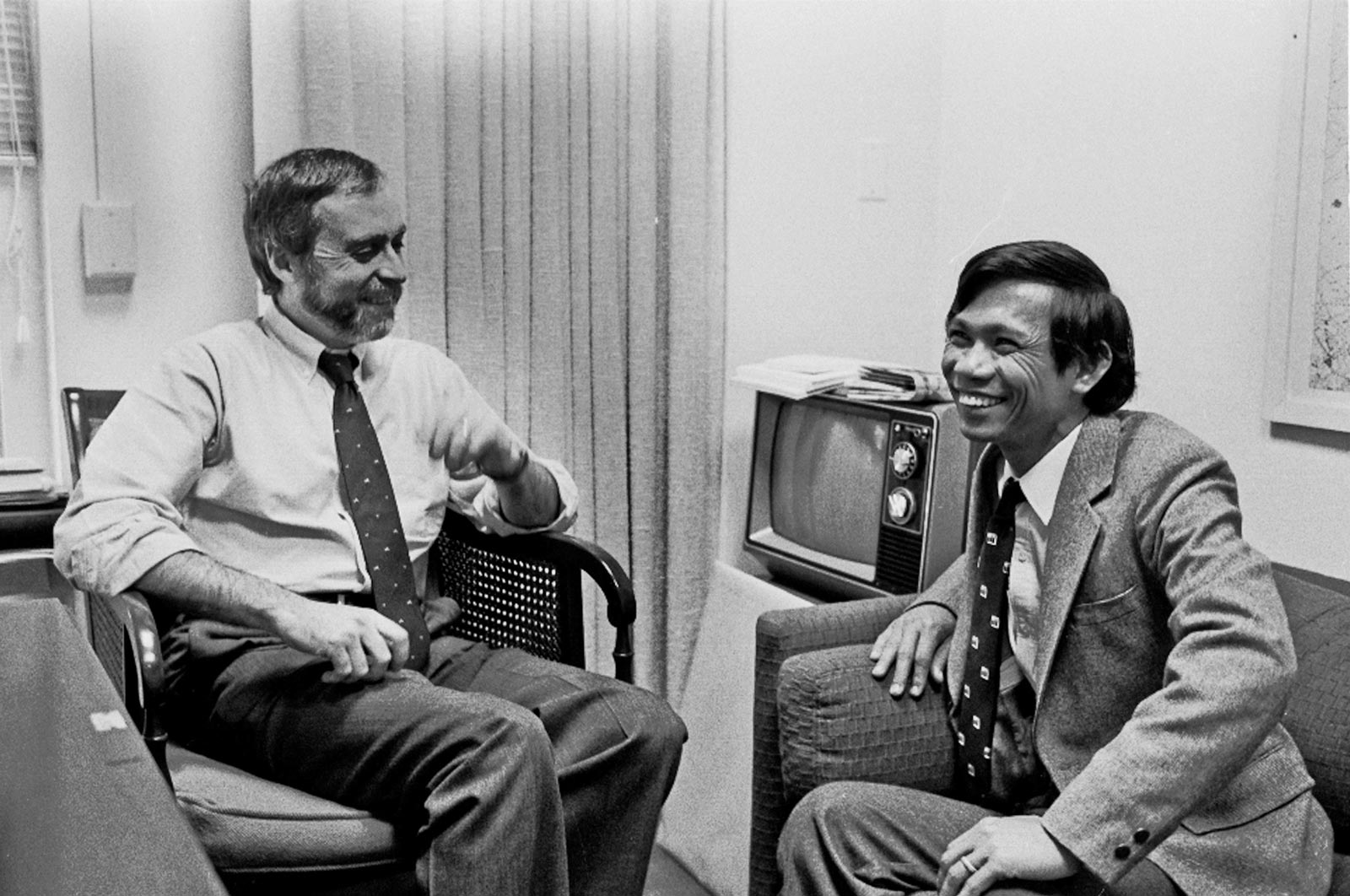

How was it having to fictionalise the real world friendship, and story of Sydney Schanberg and Dith Pran?

Interestingly, the film had been sold to me on the basis that it was this great friendship between the two of them, as this kind of love story. I had lunch with Dith Pran in New York, and he was like; “Sydney, I love Sydney, but, you know, sometimes he would slap me. If I didn’t get the right border passes for him, he would kick me.”

I mean, I couldn’t really believe what I was hearing, so I went back to Schanberg, and said, “Listen Syd – this is hard for me to say, but I don’t believe your story!” And to his great credit, he said, “Bruce, you’ve got to write what you’ve got to write.” And so he kind of handed it over to me there and then.

You do touch upon the difficult side of their relationship in the movie…

I did try, but those kinds of moments were a little deodorised by the studio. They did want me to take out a few bits that might just alienate a modern audience.

That’s interesting, as I was going to ask how you came to a decision about how much of the harsh reality of that time in Cambodia to show on screen, and how much to shy away from?

The real cruelty of the Khmer Rouge was too much to put up there, so a lot of it was implied, or was happening off screen. One of the only things I made up for the film was when they try and fake a new passport photograph for Pran when they are stuck in the French Embassy. That didn’t actually happen. And the weird thing is that when the film came out Sydney Shamberg came up to me, and said, “Yeah I remember when we did that photograph!” And I told him, “Syd, it didn’t happen”, but he was convinced “Oh no, no, it did happen Bruce!” So I bet him $100 that it didn’t, and the next day he came back to me and was like, “You’re right, it didn’t happen!”

So the truth had got blurred in his own mind?

Yeah, totally. When I had the idea for that photo sequence I started phoning around, trying to find out if it could actually be done with the proper chemicals and stuff. In the end, there was this guy at Middlesex Hospital [in the UK], the X-Ray Department. He was a photography freak, and he told me that without the chemicals, you could develop a photo with disinfectant, and you could fix the picture with piss, so that was basically what I added to the script.

Yeah, and that moment is really important structurally…

… because otherwise they are just all sitting around? Yeah, that’s what I call ‘The Bomb Under The Table’. Characters can be doing anything you want, playing table tennis, or whatever, provided there is a bomb ticking under the table.

One of the problems I had with the script was trying to figure out why the Khmer Rouge had even happened in the first place. I used to go and see this Shrink when I was much, much younger. I had a real, serious depression back then. But later on I used to go and see him just to talk about stories.

With regard to The Killing Fields, I asked him why this terrible violence turned back in on its own people? He didn’t really know much about Cambodia, but I told him about the American’s dropping something like nine billion tonnes of bombs on Cambodia during the Vietnam war, just “incase” they were hiding weapons. I mean, it’s madness. Anyway, the psychiatrist says to me that Cambodia’s rage at this was so extreme that they could only express it by turning it in on themselves. And that was a bit of a lightbulb moment [for the script] and that seemed to me to be a hook I could hang the story on.

It became apparent very quickly – that this small, Cambodian guy, and this American journalist were a kind of metaphor for imperialism.

And that idea is really quite contemporary. You could say the same kind of thing happened in the aftermath of the Iraq war in 2003, with Western interventions leading directly to the formation of ISIS; fundamentalist cells being born out of ashes, so to speak.

It certainly seems like it, even with Brexit in the UK. I mean, I remember standing in this very room, screeching at the TV, at Tony Blair talking about not leaving the European Union. He was one of the principal catalysts in the first place, by illegally invading Iraq, killing 600,000 people, and creating four million refugees who all wanted to escape a war torn land. They all came into Europe, which then triggered the hard right all over Europe.

I remember just bursting into fucking tears [when I heard about Ngor’s death], just crying about it. Because it’s so horrifying. He was just a great bloke, very smart

And there are parallels, I think, with the Khmer Rouge following the Vietnam conflict?

Yes! Of course, interestingly, it was Vietnam, not the US, that eventually sorted out the Khmer Rouge in the end.

Did you speak to any of the survivors of the regime?

I spoke to quite a lot of Cambodians who’d come out of that, who were children, or teenagers at the time. Of course, I spoke to Dith Pran himself, and of course Haing Ngor, who played him. And that was of course the great tragedy of the film, this guy, Haing had been through it all himself! He’d lost something like 11 family members during the Khmer Rouge, and then went and lost his own life getting gunned down by some punk for $40 and a watch.

In the movie there is almost a kind of dark, precognitive moment where Haing, as Pran, hands over his Rolex to some of the soldiers, which when I was watching it again, kind of took on a new edge in the knowledge that – years later – Haing himself was killed handing over his own Rolex.

That’s very interesting, I’d never even thought of that link, to be honest. I didn’t meet Haing Ngor before filming, but I met him after. He is exceptional in the film. An amazing performer. Amazing. Unbelievable really, I mean, he was a gynaecologist!

Do you remember where you were when you heard that Haing had been killed?

Yeah, I do. I remember just bursting into fucking tears, you know, just crying about it. Because it’s so horrifying. He was just a great bloke, you know, very smart. Unfortunately, now with time having elapsed, these two people [Ngor and Pran] have really merged. In my memory. In my head. I can’t remember which one said what, you know? They’re kind of the same person to me.

That’s symptomatic of what the movie does so well, which is blurring reality with the world of the movie itself.

Exactly, and that was a very cool move on Roland Joffe’s [the director of The Killing Fields] behalf. I mean in a way, why didn’t Dith Pran play himself in the film? I’ll tell you one of the most moving things that happened … We were at the BFI in London for a screening. Both Schanberg and Dith Pran were in town, and we’re all up there on this stage talking about the movie. And you know there’s a writer, a producer, an actor, whatever, up there saying “We lived this!” or “We’ve done this!” and of course, we fucking didn’t do anything. We made it up! We made a movie, that’s what we really do!

Anyway, then Dith Pran got up and made this incredible speech. He was saying, “Yes we made a movie, but this was my country! My country!” with tears streaming down his face. Honestly, my eyes were just red hot with tears, and I was straining not to cry in front of this audience. And it really was a salutary lesson – no matter what you do as a writer or a filmmaker or an actor, it’s fucking nothing compared to the real deal.