The sound of dozens of dogs barking fills the air, rising to a near-deafening pitch as visitors approach the top of a steep forested hill.

Iron gates, high walls, concrete floors and small windows abound at this government-built facility, which spans 20 two-storey blocks that house thousands of animals. Scores of dogs and cats pace about their cages and communal kennels, while others prowl restlessly around narrow walkways, eagerly clamouring for attention when a visitor pops by.

Factory-like and institutionalised – this is what has been said of The Animal Lodge, a cluster of animal welfare groups, independent shelters and pet farms in Sungei Tengah, tucked away on the outskirts of far northern Singapore.

By most accounts, the city-state has made notable improvements in handling the stray or unwanted animals that roam its 721-kilometres-squared. Programmes to sterilise stray dogs have reached most of the island’s feral population and wide-spread culling of unowned animals has tapered off in way of a more humanitarian approach.

But as Singapore remade itself into a modern, global city, it can feel as if it traded away its more laid-back roots and kampong feel – a Malay phrasing that evokes a rural village – for a squeaky clean image as a gleaming economic powerhouse. Now, the city-state straddles an uneasy balance between allocating precious land for development and allowing room for nature to breathe.

Singapore’s human population reached in 2019 an estimated total of 5.7 million people, adding roughly 1.7 million through the past 20 years. With more than 7,950 people per square kilometre, it is one of the most densely populated places in the world.

The in-fill has cramped people and animals into an at-times uncomfortable embrace and now, the concrete structures of the Lodge seem also to house fragments of the city-state’s perennial land conundrum and an at-times ambivalent governmental approach to animal rights.

The story of the Lodge began in 2016, when the former Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore (AVA) announced the construction of the facility to accommodate the relocation of more than 20 animal shelters originally located in Pasir Ris Farmway, an idyllic, city-owned space near the sea in eastern Singapore.

A wiry, grizzled man with a tendency to speak at rapid-fire speed, Mohan Div recalls how his animals once had free rein over at Pasir Ris, which was full of shady trees, dog runs, spacious green pockets, and even a pool to themselves.

“For the past 16 years, the animals were free to roam,” said Mohan, who oversees care for more than 200 cats and nearly 300 dogs at the Lodge. Beyond his day-to-day work with the animals, Mohan is also a co-founder of the Animal Lovers League, a charity that runs the largest no-kill shelter in Singapore. “They weren’t confined to a concrete cell like this. It’s clean, hygienic, but the animals don’t have the same kind of levity now. It’s very institutionalised.”

The best prospect of Pasir Ris Farmway for an animal haven was that it was a large plot of open land in a city that hungers for space. Ironically, this same asset would eventually be the undoing of its use for the animals, thanks to the city-state’s burgeoning construction and development economy. This year alone, Singapore has US$20-24 billion in public and private sector building projects on the books.

Soon after the farm was handed back to the government and the animals carted off, the shady acres were set aside, likely for new projects.

While there’s little-to-no truly wild places in tiny Singapore, the city has still developed with a keen eye for greenery, mostly in an elaborate park system and other quality-of-life features designed with humans in mind.

That can have direct benefit for animals, especially smaller creatures who can make a quiet home with the parkland.

But as the natural world is condensed and packaged into an increasingly sterile and urbanised cityscape, some citizens are becoming more intolerant of nature and wildlife when they happen to encounter it.

Most often, that appears in numerous complaints to authorities, who have assumed bureaucratic oversight for everything from monkey attacks and wild boar sightings to noisy mynah birds roosting near homes. In the near past, a common approach of city managers to problematic animals was to kill them to reduce their numbers in a practice known as culling.

Back in the old days, Singaporeans were no strangers to the animal world. Aside from chance meetings with wildlife, it was quite common to grow up with plenty of non-human creatures such as dogs, chickens and horses.

Now, with a cultural trend to much more formalised and structured interactions with any of these domesticated beasts, animal welfare workers are wondering if something genuine has been lost in development.

“They were ubiquitous and people didn’t mind them,” Mohan mused about animal neighbours in the old kampong communities. “It was all about give and take.”

“[But in Singapore], if you continue to take every complaint so seriously and put them down, people will keep thinking that they are a menace, when they are just cats and dogs,” he adds. “Singaporeans tend to be very kiasi [a Hokkien phrase that describes a fear of dying]”.

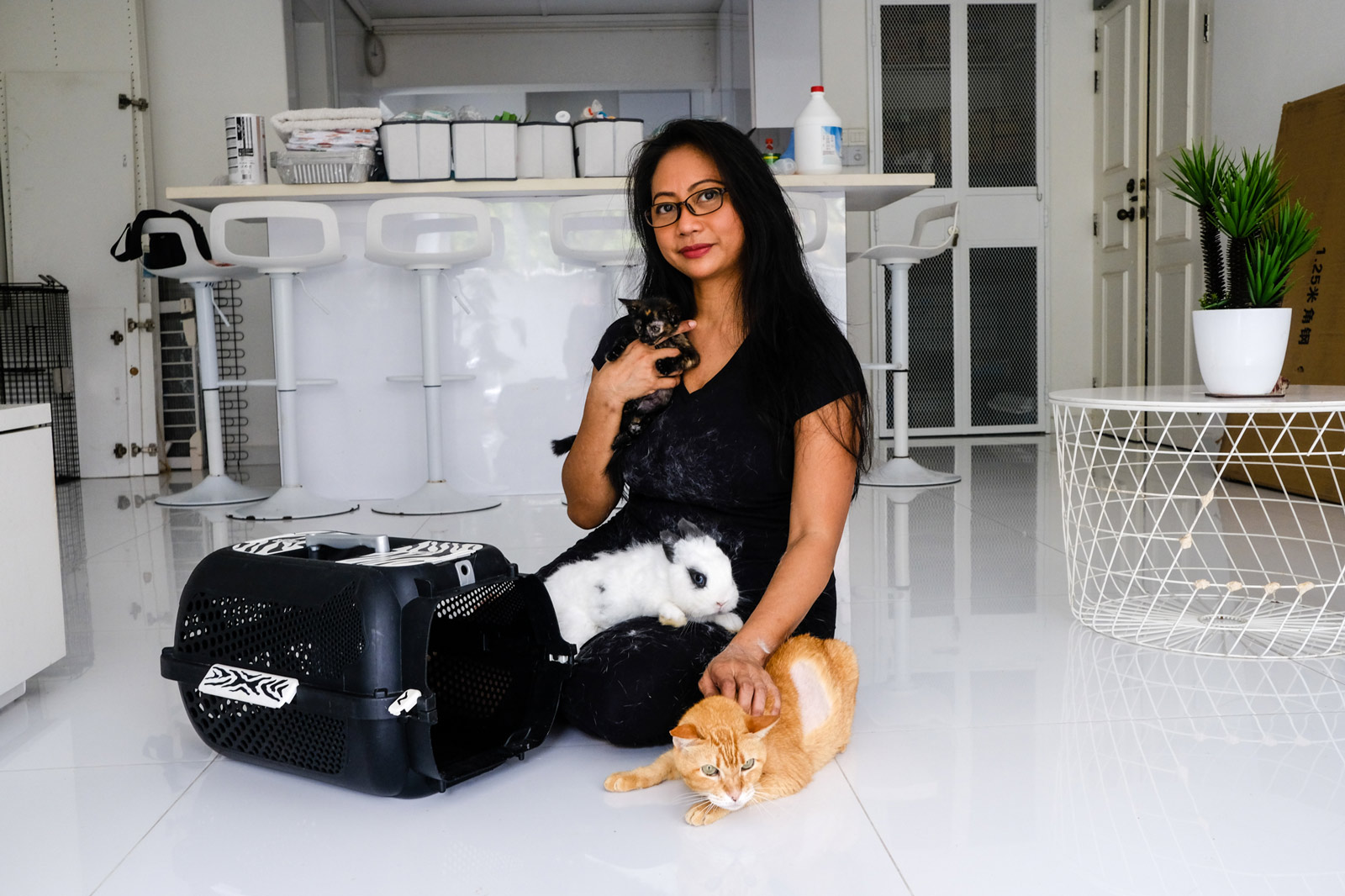

Nur Samad, 47, is an independent animal rescuer known to the community as one of the “Kitty Ladies of Singapore”, a small tribe of women who have made it their mission to care for wayward felines. True to her creed, Nur carries a rescue carrier everywhere she goes, complete with a rescue kit stuffed with thick gloves for “fierce-ish cats”, wet wipes, disposable gloves, kibble, toilet rolls and nail clippers.

She says animal rescue and care often falls to independent citizens like herself despite the large public system that underlies Singaporean society. She argues that animal welfare seems to be at the bottom of the government’s list, because there is no monetary or political gain to be had from it.

“Animals don’t vote and they can’t contribute to the economy, so they get sidelined,” she said. For her, that includes an often frivolous attitude of reporting and enforcement of stray or loose pets that often fails to actually address the welfare of the animals.

“I’ve heard so many ridiculous complaints to the town council. One woman complained about seeing a cat on top of her husband’s car. Another said, ‘My family is afraid of the cat, please remove it.’ And the town council actually placated them and wanted the cat gone,” she said in disbelief.

As Singapore developed into a modern, highly bureaucratic state, its citizens have increasingly turned to institutions to mitigate wildlife encounters.

The fearful or disdainful attitudes toward such animals can breed other problems.

Nur said many animal abandonment cases can fall through the cracks due to unclear or unenforced public codes. When that happens, the responsibility can fall to bystanders like her and other concerned neighbours.

Unlike dogs, cats are banned in Housing Development Board (HDB) flats. This form of public housing houses 80% of Singapore’s resident population, mostly in high-rise apartment complexes.

But the rules about pets aren’t always enforced in these developments and, as a result, a policy grey zone has formed in which cat abandonment, illegal home breeders and sellers, and even animal hoarding can run rampant.

Backyard breeders looking to cash in on this lucrative industry engage in “blatant breeding and selling”, while others post on secret Facebook groups. Most end up “getting away scot-free” or just slapped with a fine, even after being reported to the authorities.

When complaints came in, the animals would be put down. It became an exercise in annihilation, too much of unnecessary killings. But now everything has changed

The free flow of animals and sporadic enforcement of anti-cat regulations has caused a serious issue, according to Nur. In just one month last year, she says she witnessed 150 cats abandoned islandwide.

She felt compelled to convert her own HDB flat into a makeshift shelter to house some 20 cats and nurse them back to health for adoption. She forks out at least $1,000 (S$1,500) monthly out of her own pocket for food, supplies, deworming and medication.

Professing to be “loud, gung-ho and potty-mouthed”, Nur takes a harsh stance against errant cat owners and breeders, often stepping in to convince owners to sterilise or handover the animals, reporting them and sharing cases on Facebook.

Still, she wonders why such a heavy burden lies on independent rescuers and on vigilantes working on the ground like herself to take care of the problem.

“A lot of us cat rescuers are getting very fed up, because we do so much and we don’t get anything out of it,” Nur said. She thinks removing the cat ban and replacing it with “explicit, immediately enforceable” laws and penalties for owner conduct would help to stamp out these problems and penalise recalcitrant breeders and hoarders.

“Clearly, the ban hasn’t worked,” she said.

Regardless of who handles them, once strays are on the streets, they end up becoming someone’s responsibility. Culling the animals has fallen out of favour with the city, so, more often than not, animals will pass through shelters such as those at the Lodge.

However, the people who oversee the operations there say it was difficult at first for both human and animal tenants to get used to the new facility.

Mary Soo, 72, co-founder of Oasis Second Chance Animal Shelter (Oscas), said the drastic change in living environment was a cultural shock. She describes their new home in Sungei Tengah as a “modern factory style setting”.

She still reminisces about their previous space at Ericsson Pet Farm in Pasir Ris. The set-up was rustic and open, with more space and opportunities for interaction between neighbours and bigger kennels with an open view of the surroundings.

“We were all filled with despair for our dogs who were being confined like prisoners in far smaller kennels”, she said of her feelings at the time. Though the animals have adapted, Mary still feels an occasional pang for what was lost. “The sad thing is they don’t get to look outside.”

Ray Yeh, 50, is the owner of BFF, a shelter at the facility that holds 100 cats and 25 dogs across two units.

With a few creative tweaks to the configuration, Ray has created a bright and cheery open-concept space, complete with hand-painted murals by children and artist friends. His cats recline in swinging baskets or clamber up several “levels” on make-shift shelves. His dogs bound up and down an elevated platform or race to the gate to greet visitors in one big, messy, slobbering group.

I understand that space is limited in Singapore, but it’s how we play around with it to make the animals as comfortable as possible

For Ray, making due with less room was a top priority.

“I understand that space is limited in Singapore, but it’s how we play around with it to make the animals as comfortable as possible,” he says, recalling how he stayed overnight in the first week of the move to get his animals used to the unfamiliar environment.

Nevertheless, the groups at the Lodge have observed a distinctly positive change in attitude toward animal welfare within the city-state bureaucracy.

Part of that was structural, mostly seen in the way responsibility for animals was divided among government agencies. The AVA was overhauled last year and remade as the Singapore Food Agency and the Animal & Veterinary Service (AVS), which is placed under the oversight of the National Parks Board (NParks).

NParks now directly oversees operations at The Animal Lodge, with AVS acting as the main point on animal and veterinary matters in Singapore. AVS is also the first responder for all animal-related feedback.

Before the institutional restructuring, according to some of the Lodge organisers, culling was a key tool in controlling the population of strays. Mary says that among other things created an “adversarial” relationship between AVA and animal welfare groups.

But in her 40 years spent helping dogs, Mary has observed an “encouraging shift” in the authorities’ perception of strays and the efforts now being put into helping them instead of just culling all of them. They are more compassionate and consultative, she says.

One landmark move to safeguard the animals’ welfare was the Trap-Neuter-Release-Manage (TNRM) programme launched in 2018, a collaboration between AVS, animal welfare groups, veterinarians and other stakeholders. It advocates a humane, science-based approach to managing the stray dog population by targeting to sterilise more than 70% of Singapore’s stray dog population within five years, and subsequently rehoming them.

Jessica Kwok, a group director of Animal & Veterinary Service at NParks, told the Globe that some 990 stray dogs have so far gone through the programme. More than half of those dogs are being fostered or have already been rehomed.

Back then, if the animals were captured, it’s the end of the road for them

Mary describes the TNRM programme as a “game-changer”.

“Back then, if the animals were captured, it’s the end of the road for them,” she said. “But now, we are all working towards the goal of animals being in the same environment safely and living out their lives without being a threat to the public and vice versa.”

More adoption drives, ongoing consultations, informal lunches and meetings, and easy access to top management on the phone – these are all ongoing trends indicative of a more “participatory” climate, she adds.

Mohan also agrees that the TNRM initiative has brought about a “colossal” change, a far cry from the previously “reactive” authority undertaking measures considered overly draconian for the modern day.

“When complaints came in, the animals would be put down. It became an exercise in annihilation, too much of unnecessary killings. But now everything has changed,” he says.

Even the Lodge is starting to reflect the new approach to animal health and safety.

NParks reduced rental rates for the non-commercial tenants to make it easier for them to keep space in the facility. At the same time, Kwok said her office used tenants’ feedback to guide renovations at the facility.

While the kampong feel might not yet be restored, the pets at the Lodge now have new dog runs on turf areas and shade-providing trees to cool the premises while adding greenery.

“We are continuing to work on more infrastructural improvements,” Kwok said. “Animal health and welfare are of utmost importance to NParks, and we are constantly reviewing measures and looking into additional avenues to work with the community to strengthen animal health and welfare standards.”

Just recently in early March, city authorities announced a slew of new reforms aimed at making it easier and safer to keep animals at home. These included allowing bigger, mixed breed-dogs to be rehomed in HDB flats, strengthening license conditions for commercial pet breeders to better scrutinise issues in housing and healthcare, and expanding the traceability of the animals involved in breeding.

Singapore might still have a way to go before ensuring the health and safety of all its residents, no matter if they walk on two legs or four. But for the tenants of the Lodge, there’s plenty to wag a tail about.

One balmy Thursday afternoon, the volunteers load up several dogs onto a chartered van and make the 40-minute drive from Tengah to Changi Beach Park, located at the opposite end of the city-state.

This is Oscas’ “palliative care” service for its old and ailing dogs like Ruby, Pepe and Bam Bam, which suffer from conditions like cancer and kidney failure. Although they are too weak to walk on the sand, Mary said it’s a nice change for them, away from the confining facility.

“They can look around, enjoy the sea breeze, enjoy a change of environment,” she said.