In May 1962, Ing Giok Tan and her parents boarded a rusty old boat in Jakarta to flee the terrible consequences of growing anticommunist sentiment. By this time, the young girl’s country, Indonesia, had become one battleground in the wider Cold War struggle between communism and capitalism.

Her family set sail for Brazil, having heard from other Indonesians who had already made the journey that this place offered freedom and opportunity for many migrants fleeing conflict. After a gruelling forty-five-day voyage across the world, her family arrived in São Paulo on Brazil’s southeastern coast.

However, their attempt to escape the violence of the Cold War was tragically ill-fated. Two years after they arrived, in 1964, the military overthrew President João Goulart, and with it Brazil’s young democracy, establishing a right-wing military dictatorship that lasted until 1985.

What happened to Ing’s family was perhaps more than just bad luck. Over the course of the last decade, new information has been surfacing about US complicity in Indonesia’s anticommunist purges half-a-century ago, as well as the direct effect this had spurring Latin America’s own political violence.

During this period, anywhere from 500,000 to three million real or suspected communists and their sympathisers were brutally murdered in mere months between late-1965 and early-1966 by the Indonesian army and “death squads”.

Now, the recently published book The Jakarta Method, written by journalist Vincent Bevins, explores how these brutal events, which leveraged America’s eventual Cold War victory in the 1990s, were enabled by Washington and crucial in cementing global systems of power that persist to this day.

We still don’t have all the C.I.A. files from the 1960s in Indonesia … I called them up to ask what they had done with them, but they chose not to tell me

Bevins was well positioned to tell this story. Having served as a foreign correspondent in Brazil and Indonesia for the L.A. Times and the Washington Post respectively, he was familiar with the history of US-backed coups in the Global South and their present effects. The result of his experience is a character-driven analysis of dark events in world history that are rarely understood to be connected.

Despite his background, Bevins still faced many roadblocks while researching this story, as all governments involved “still maintain official secrets from the period” he told Globe. In Indonesia, particularly, the anti-communist terror of the 1960s remains a highly taboo topic, rarely discussed.

“We still don’t have all the C.I.A. files from the 1960s in Indonesia,” he said. “I called them up to ask what they had done with them, but they chose not to tell me.”

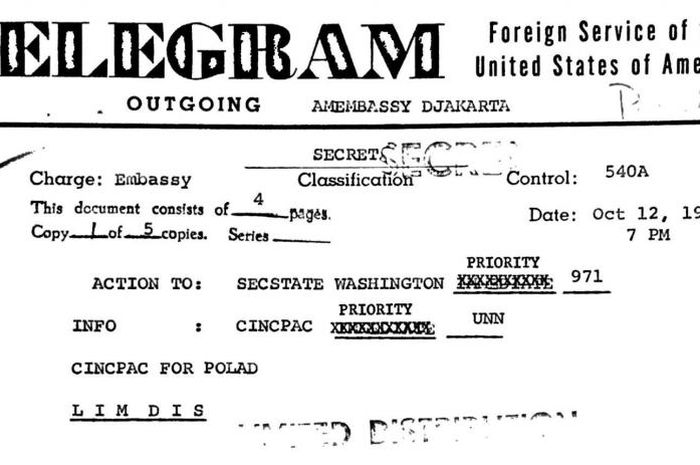

What Bevin’s did have, however, was a series of US diplomatic telegrams from the period, published in 2017 by the National Security Archive and the National Declassification Center.

From having knowledge that many of the massacred had no affiliation to the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), to offering to help suppress media coverage, the files showed that the C.I.A. assisted in the killings and used Indonesia as a model for repression elsewhere – a fact Bevins was able to explore in The Jakarta Method.

This is why Bevins describes his work as “a global story, perhaps more about US hegemony than anything else”.

A significant factor resulting in Indonesia becoming a focal point for US geopolitical anxieties was its founding-father Sukarno, whose popularity came from his attempts to craft a singular Indonesian identity – a mean feat given that the more-than 17,000 islands forming the vast archipelago nation had little in common other than having been Dutch colonies.

Through harnessing anti-imperialist sentiment, the nation’s first leader tried to synthesise the many different Indonesian cultures into a single, left-leaning project.

He was also one of the most significant proponents of Third-Worldism, which, despite the more negative connotations of the phrase nowadays, was a forward-thinking non-aligned movement meant to unite the peoples of the formerly colonised world.

The US and other countries in the Global North were perturbed by this developing movement. These concerns reached a critical point in 1955, when Sukarno played a key role in organising the Bandung Conference – the first large-scale meeting of Asian and African heads of state.

By this point Sukarno was firmly on the US radar as a threat, not just for what political movement he might lead in Indonesia, but for the stir he appeared to be causing across the Global South.

Despite mounting suspicion around Sukarno’s political affiliations, he was not radically anti-capitalist. Neither was the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) by many accounts, despite the Partai Komunis Indonesia – founded in 1914 – becoming the third-largest communist party outside China and the Soviet Union by the time it was banned in 1966.

By all accounts, including declassified C.I.A. documents, the PKI were gaining influence in Indonesia through elections and community outreach. The US had been trying to stop the PKI for over a decade, treating them like an insurgency despite understanding that they had gained popularity through legitimate means.

By the mid-50s, the US had successfully orchestrated coups in Guatemala and Iran, and by the 1960s the C.I.A. would turn its new box of tools on the Indonesian left with US President John F. Kennedy and British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan in 1963 agreeing the need to “liquidate President Sukarno”.

As Sukarno began to suspect that the US was trying to overthrow him, the Indonesian leader strengthened alliances with communist countries and ramped up anti-American rhetoric in 1964.

At this point, the US began to back military general and strongman-in-waiting Suharto – training, financing and arming military officers. The US would also assist Suharto in further spreading anticommunist propaganda, with Washington covertly supplying vital mobile communications equipment to the Indonesian military, a now-declassified cable indicates.

After months of tension between the Indonesian army and Sukarno loyalists, killings of leftists started in October 1965 in Jakarta, eventually spreading to Java and Bali. An accurate and verified count of the dead is unlikely ever to be known, though most scholars now agree that at least 500,00 were killed in several months.

To this day, discussion of what happened is heavily taboo in Indonesia.

The survivors

The highly taboo nature of the topic is why, when collecting first-person accounts for The Jakarta Method, Bevins spent two years “very slowly getting to know the various survivor groups”, explaining the project and making sure it was something they wanted him to do.

“It was paramount that I respect their version of this story,” he said, adding that his slow and gentle approach “meant a lot of trips, and a lot of time just living near survivors, waiting until things could move forward organically”.

Sunaryo

While researching this project, Bevins compiled portraits of lives touched by the brutal anticommunist purge. That includes people like Sunaryo, a man Bevins got to know and who in his younger years was a member of the PKI. In 1965, Sunaryo was imprisoned for his affiliations. His friends were killed for theirs.

Wayan Badra

Another of Bevins’ interviewees was Wayan Badra, a priest and village leader in Seminyak, Bali. He told Bevins that he fondly remembers studying under communist teachers in the 60s. He also described the many times he has given Hindu funerals for the bones still being uncovered during the construction of new beach hotels.

Magdalena

Magdalena, an important character in the book, was not politically active during the 1960s, but was a member of a union that represented workers at the garment factory at which she was employed.

Showing the extent of the McCarthy-esque hysteria of that time, that alone was enough to attract the ill-attention of anticommunist authorities who arrested and imprisoned her in 1965. Today, she lives in poverty in Solo, Indonesia.

Sumiyati

As a girl, Sumiyati was a member of Gerwani, the Indonesian Women’s Movement, in Central Java. Organised along feminist and socialist lines, Gerwani was one of the largest women’s organisations in the world, until 1965. As part of Suharto’s anticommunist propaganda facilitated by the US, the army said the Gerwani kidnapped generals and castrated them in demonic, sex-crazed attacks.

“I find it incredibly tragic, but very plausible, that we will not ever have a moment in which all survivors of 1965 feel comfortable speaking freely about what happened,” said Bevins.

“That would mean that a moment of national reconciliation, or at least full honesty about the past, could only come with younger generations, but that would not make it less important.”

And with many C.I.A. files from the period still classified, it’s entirely possible that this story will continue developing for decades to come.

The Jakarta Method: Washington’s Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World can be bought here.