When the pandemic struck, Bo Sarapai knew he would soon have to leave Bangkok. As a motorcycle driver, he roamed the streets of the megacity to deliver goods and people, sticking through the first and second waves of Covid-19 in 2020.

But as the city quieted down once again in the third wave of infections that started in April, living in Bangkok was, for him and his family, an investment with minimal return. The 35-year-old packed up last month, along with his wife and two daughters, and left for his home province Surin in northeastern Thailand.

Bo joins a growing cohort of people doing the same, with over 127,000 people moving out of Bangkok in 2020 according to the National Statistical Office, as the city recorded its slowest population growth in two decades. Official statistics also showed that over 1.05 million migrated internally in Thailand in 2020, a 60% increase compared to 2019, largely due to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Many low-income workers experienced reduced working hours, minimal pay and layoffs, leading them to return to their hometowns – effectively reversing the typical flow of migration into the city in search of a better life.

“It was the best decision,” Bo said. “Since Covid came, there has been way less traffic. My income dropped dramatically. Each month would be digging into my savings to pay for all the expenses to live in Bangkok.”

In an April report, Bank of Thailand economists presented this outflow of labour as an opportunity to improve Thailand’s economic development outside the capital – long tilted heavily towards Bangkok – especially in the agriculture sector. But without intervention and support from the government, the chances of that seem to remain slim as many struggle to stay afloat in their home provinces, mainly keeping up with expenses whilst employment prospects remain low.

For decades, Bangkok has been the epicentre for Thailand’s rural-to-urban internal migration, which has historically made up 60% of Thailand’s total internal migration as cities lure in people through job opportunities and higher incomes. The largest demographic that has moved to Bangkok has been people from Thailand’s northeastern region of Isaan, who are mostly transitioning from agricultural work to jobs in the service sector.

But this is a trend that has flipped in the past 18 months, according to Dr. Somchai Pakapatwiwat, an economic expert and previously a social advisor to the United Nations ESCAP.

“There has been a [migration] trend for the past one and a half years of Covid, approximately about 2 million migrants – both ways – mostly from Bangkok to other provinces. The number is quite high,” he said.

“During the Covid pandemic, there is [greater] tendency towards migration from urban areas to rural areas due to the particular problem of having no employment or under-employment, not only labourers but also shopkeepers,” said Somchai.

With each wave of Covid-19 infections forcing Bangkok to shutter – first from March to June last year, then in December, and now since April in the deadliest outbreak yet – many businesses employing internal migrants have closed, causing their workers to consider returning to rural hometowns.

The main cities that have seen an exodus of people are those where tourism-dependent employment is an important factor, such as Bangkok, Chonburi and Phuket, reports the Bank of Thailand. On the receiving end, migrants are flowing back to provinces in northeastern Thailand as well as Nakorn Sri Thammarat province in southern Thailand.

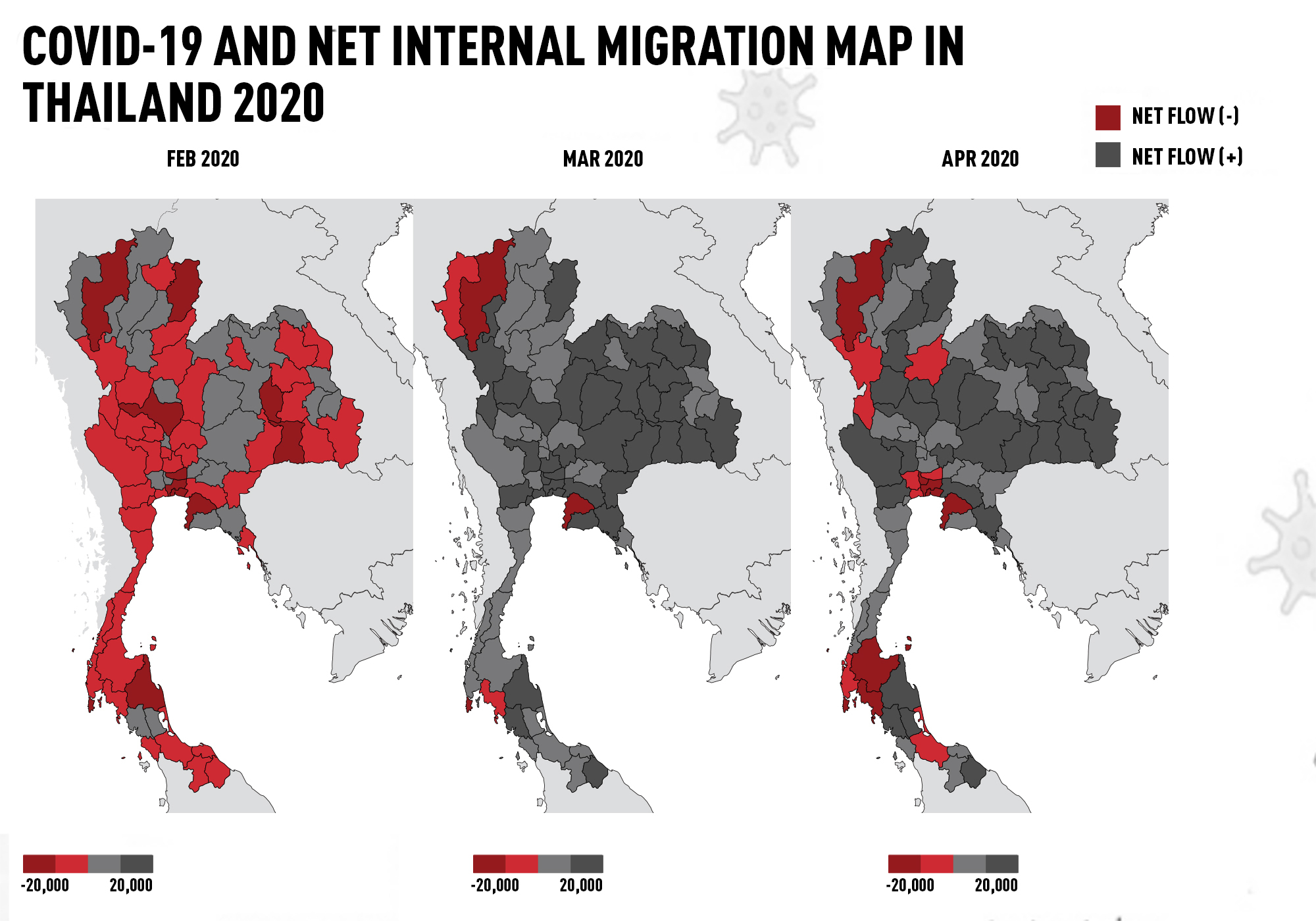

The migration flurry was at its peak at the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020. While official statistics showed just over 1 million people internally migrating, mobile phone data from Thailand’s second-largest operator True Corp showed that during the first wave of infections between February and April of last year, 2 million Thais left Bangkok and other major cities to return to provincial areas. Of that, 58% of the migration flow in February was out of Bangkok to other provinces.

Among this tide of people was Chompoo Samanmit, a 39-year-old who left the capital once the cafe at a bed and breakfast she was working at announced it was closing down. Stuck in a relatively expensive apartment without employment, she decided to move back to her home province, Nong Khai.

When she first moved, Chompoo had hoped to open a small coffee shop of her own but instead has been juggling work in gig employment.

“It’s like catching two fishes with each hand. I don’t have the resources to open a shop on my own and I also need to find income,” said Chompoo. “So the only option I really had was to find a job with other employers around Nong Khai.”

This reverse flow of urban-to-rural migration has been a feature of every major economic crisis in Thailand, the Bank of Thailand stated. From the 1997 Asian financial crash to the 2007-08 global financial crisis, the agricultural sector in rural areas has served as a cushion for low-income workers in the city when the urban economy slows.

But this time, with the extended and seemingly indefinite interruption provided by Covid, combined with a more tech-savvy Thai population that exists today, there has been hope that this wave of returning migrants could bring growth and development to their destinations.

Bank of Thailand economists Saovanee Chantapong and Warit Tassanasunthornwong proposed in the April report that those migrating from urban areas could develop rural areas by importing their tech literacy.

“This is a rare opportunity for such a big migration of modern workers, who have knowledge and technology, to return to their hometowns,” the pair wrote.

But others are less optimistic, with Somchai feeling more cynical about the prospect of rural areas benefiting from this urban exodus. Though there is an opportunity in this crisis, he says there are few tools available to make the best of it, especially if looking to the longer term once employment opens back up in city centres.

“If you work in the urban area, you are specialised in the service sector, it will be very difficult for you to turn yourself to work in the agriculture sector,” said Somchai. “If you look in the past, a lot of agricultural workers changed to work in the service sector – very few then go back to agriculture.”

For Bo, the motorbike driver in Bangkok, going back to Surin province to grow rice is something he has done annually for much of his adult life. But this time round, completely relocating his family in Bangkok to live in the countryside for more than just the harvest months, he appreciates just how much more challenging this line of work is.

“[Harvesting rice] is tremendously harder than driving a motorbike in Bangkok. There’s attention required for every detail and investment is required throughout the process,” said Bo. “Then when you finish harvest, the sale price is dependent on the price for the season – we have to risk it there.”

The prospects for Thailand’s rice sector look shaky, seeing year-on-year exports drop 23% in the first quarter of 2021, with Vietnamese producers hot on the kingdom’s tail and looking to leapfrog the kingdom as the world’s third largest producer.

Despite these downsides, for now the situation is still more favourable than staying in Bangkok, Bo says. The perks of living in Surin have been immediate as his family expenses have more than halved.

“At the very least, eating has become so much easier – being able to cook from what’s around,” Bo said. “In Bangkok, everything is bought and that adds up to a large sum.”

So far, assistance from the government to families such as Bo’s has come in the form of money packages. The government has issued a 3 trillion baht ($96 billion) stimulus package which has been turned to the We Win financial aid programme, a cash handout for February and March this year to over 32.4 million eligible citizens. This is on top of a We Love Each Other subsidy scheme and a co-payment scheme for purchases at designated stores.

Somchai sees these government programmes as having been rolled out to accommodate the expected outward migration. Still, financial aid alone will likely not be able to improve agricultural productivity or stir development in small city centres as some hope to see. Lasting changes such as that will require more targeted policies, Somchai said.

“In order to make that goal achievable, the government has to focus a lot more on the agricultural sector and help in terms of labour, re-skill all these people to a level that could improve the situation,” he explained. “Of course, [urban migrants] are more educated, but turning education into practical development is another matter.”

“Migration itself is a fragmented development, but not a structural one.”

Returning to Bangkok, I feel like it will happen. It’s just a matter of when. I’m just waiting for the pandemic to fade and for more restaurants to open up

Today, Thailand remains gripped by new cases of Covid-19 still emanating from that April outbreak, complicating efforts from the government to quickly reopen the country for tourism. But this roughly once-a-generation migration trend, from urban to rural, is expected to flip once Bangkok does reopen.

“I expect that 80% of those who migrate to other provinces will be back,” said Somchai. “These people are quite education-oriented and their mindset is not with agriculture.”

That’s the case for Chompoo, who sees her time back home province as a form of wintering for the time being until the pandemic situation improves.

“Returning to Bangkok, I feel like it will happen. It’s just a matter of when,” she said. “I’m just waiting for the pandemic to fade and for more restaurants to open up.”