Meedee Korn does not want to name the religion he believes is threatening Buddhism in Thailand. He means Islam, but refuses to say this, even after several prompting questions. He simply refers to it as “a religion”.

“There is a religion that wants to take advantage of this country,” said Korn, a bespectacled, middle-aged man who speaks just above a whisper and in short, clipped sentences. Proving just as reticent when it came to providing examples of how Muslims are supposedly taking advantage of Thailand, he adds elusively that “if other religions want to destroy Buddhism in Thailand” it is the duty of the faithful to prevent it from happening.

Korn is the secretary of the Committee to Promote Buddhism as the State Religion (CPBSR). Formed late last year, its goal is to lobby the government to, as its name suggests, make Buddhism the official religion of Thailand. Since the first of Thailand’s 18 constitutions was declared in 1932, Buddhism has never had this designation. But when the military junta came to power in last May’s coup, they abrogated the former constitution – that required the government to “patronise and protect Buddhism and other religions” – and are currently writing a new one. The CPBSR hopes to persuade those responsible for the drafting to accept their agenda.

According to Korn, Buddhism in Thailand is also being attacked from ‘within’. He worries that the immoral behaviour of monks is increasing and that this is “destroying” the reputation of the religion. Stories of monks being caught drinking alcohol, taking drugs and visiting prostitutes have been reported frequently by the country’s media in recent years. Making Buddhism the state religion, he said, would not only protect it from the alleged onslaught of Islam, but would also create new powers to punish ‘immoral’ monks with formal legislation, rather than just by the customary practice of defrocking.

Since the CPBSR arrived on the scene late last year, commentators have been divided over its significance. One suggestion is that the effort to make Buddhism, the religion of more than 90% of the population, Thailand’s state religion is the caprice of a few opinionated individuals who are unlikely to meet with success. As a Bangkok Post editorial in October put it: those responsible for drafting the new constitution should “dispose of this matter quickly, and move on with important matters”.

However, another view is that the movement to make Buddhism Thailand’s state religion reflects a much larger issue: the radicalisation of Thai Buddhism, fuelled by anti-Muslim sentiment. During the past few years, a great deal of attention has been paid to Buddhist extremism in Myanmar, the rise to prominence of the Mandalay monk Wirathu – who was dubbed “The Face of Buddhist Terror” by Time magazine in 2013 – and the hardline Buddhist nationalist Ma Ba Tha movement that has successfully lobbied the government to introduce both pro-Buddhist and anti-Muslim legislation.

Now, attention is shifting to Thailand, as the opinions of some of country’s Buddhist officials appear to be swinging to the extreme. On October 29, 2015, a high-ranking Buddhist monk from a Bangkok pagoda wrote on his Facebook page that a mosque should be “burned” for every Buddhist monk killed, adding that this eye-for-an-eye retribution should start “from the northern part of Thailand [heading] southwards”.

In a November Reuters article, these comments were used a few paragraphs below those of Somchai Surachatri, a spokesman for the National Office of Buddhism, a government agency, who said Buddhism could one day be “devoured” in Thailand, adding that he feared Muslims were buying land to build mosques throughout the country.

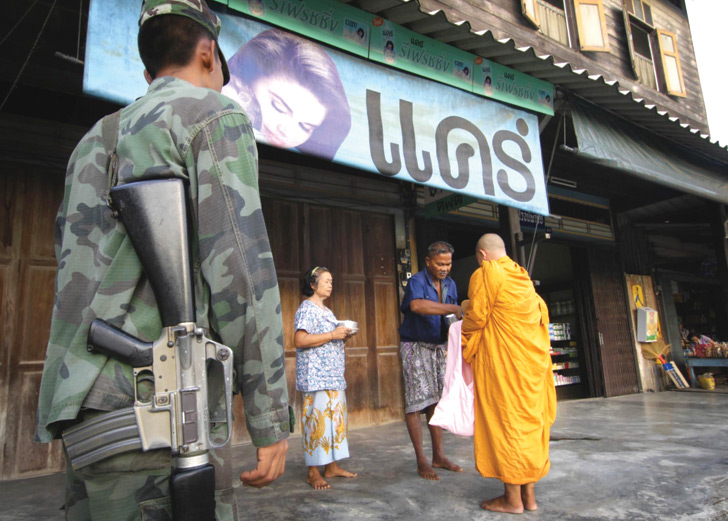

Since 2004, tensions have escalated in Thailand’s three restive southern provinces, where the population is mostly comprised of Malay-speaking Muslims. There, a bellicose insurgency movement has fought for autonomy for decades and, during the past ten years, more than 6,000 people have been killed in the struggle. On occasion, Muslim insurgents have murdered Buddhist monks.

In a 2009 essay, Duncan McCargo, a professor of political science at the University of Leeds, described “a growing sense that Buddhism was under threat from a resurgent and militant Islam concentrated in the south.” He added that the rise of “Buddhist chauvinism” counters claims that the religion is “inclusivist and tolerant.”

However, speaking to Southeast Asia Globe, McCargo said that efforts to make Buddhism Thailand’s state religion were not simply motivated by anti-Muslim sentiment, nor was the growth of Buddhist extremism in the country a mere imitation of what is happening across the border in Myanmar, as some commentators have suggested.

As he noted, the CPBSR is not the first group to campaign for Buddhism to be made Thailand’s state religion. An unsuccessful effort was launched in 2007, following another military coup that abrogated an earlier constitution and set about creating a new one.

Instead, according to McCargo, efforts to make Buddhism the state religion of Thailand reflect a growing “set of collective national anxieties” among Thais, which go to the heart of the country’s self-identity.

During the past two decades, Thailand has undergone monumental social changes. The World Bank puts Thailand’s rate of urbanisation at 1.4% each year – just below the regional average. As anthropologists have documented over the past two centuries, urbanisation results in traditional ways of life being severed. Family bonds often make way for individualism, community ties are cut, social classes are revolutionised and the symbols of self-identity must be altered.

“In Thailand, discourses concerned with urbanity/rurality are played out every day in the Thai media, education, economy, politics, so that Thais are always aware of these spatial differences,” wrote James Taylor in his book Buddhism and Postmodern Imaginings in Thailand.

Globalisation and the growth of capitalism have also irreversibly altered the way many Thais live and think, and the legacy of the 1997 economic crisis continues to linger, casting doubt among the populace on the benefits of ‘progress’.

The result, argues Taylor, is that “Thai people feel more insecure than at any time in the past”. Because of this, he wrote, “Thai Buddhism… is caught in the contradictions of history and tradition.”

According to Taylor, the impact of ‘modernity’ and Western influence on Thailand is often believed to be leading to “secularisation and [religious] disenchantment… Buddhism [in Thailand] is seen as increasingly marginalised or privatised.”

However, what Taylor found in Thai cities was a growing nostalgia for what he calls “country things”, especially the traditional position of Buddhism at the centre of rural Thai society. “It seems that middle-class urban Thais have a nostalgia for an imaginary rurality and its contentment,” he wrote.

Such nostalgia has led many Thai urbanites to imitate rural ways of life, such as wearing rural, traditional clothing or purchasing country homes for weekend escapes. It is even reflected in popular culture, such as in the nang yon yuk, or ‘returning to the past’, film genre. Taylor argues that this represents a search for permanence at a time when society is changing, and one element that “insecure” Thais have clutched onto is Buddhism, which he adds has long been a “signifier of Thai-ness”.

Pavin Chachavalpongpun agrees. The associate professor at Kyoto University’s Centre for Southeast Asian Studies said that since Thai society is undergoing a “major and fragile transformation, Buddhist extremism has found its way to dominate social thought”.

Declaring Buddhism the state religion, he continued, would provide some much-needed stability by giving Thais a consistent reference point for self-identity. “It would boost a sense of nationhood based on Buddhism – this would also lead to a sense of nationalism,” he said.

Or, as McCargo put it: “Making Buddhism a national religion forms part of an attempt to return to imagined earlier certainties and unities, and to reify and reinforce the existence of a ‘Thai-ness’ that now seems increasingly elusive.”

But it is not only society that is undergoing fundamental changes. At the same time, Thailand is also experiencing political transformations – or, some might say, political anarchy.

For more than half a century, Thailand has lurched from one political crisis to another, as elected governments are overthrown by military coups only for the entire cycle to repeat itself. The more recent conflict began in 2006 when the elected prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, was ousted in a military coup. This resulted in political divisions between Thaksin loyalists, often dubbed the Redshirts, and the so-called Yellowshirts, made up of the conservative urban middle-class and elites who have thrown their weight behind the current military junta. “There is the sense that there is no way out of the country’s hopelessly polarised politics,” McCargo said.

One way to provide some stability to this political confusion, said Chachavalpongpun, would be to promote Buddhism as a form of social cohesion. “Particularly now that Thailand is under the custody of the military, an obedient society is needed. And Buddhism can be used toward fulfilling that agenda,” he said. This is why he believes there is a good chance that Korn and the CPBSR will be successful.

“The state will be able to use this as a tool to create a sense of sacredness for itself in the same way as the lèse majesté law is used,” the Buddhist scholar Vichak Panich told the Bangkok Post in October.

If the military junta does use Buddhism to create order and curb dissent, it would hardly be innovative. As McCargo wrote in a 2004 essay: “The Thai sangha [Buddhist order] has long been an uncritical collaborator with the state, legitimating the state without comment and without reproof.”

If Buddhism does become Thailand’s state religion, it could create some stability in a country where it is lacking. Critics of the military junta, however, would argue that this would not be stability as much as control. There is also the very real concern that it would escalate an already perilous situation in the country’s southern provinces, where much of the Muslim population feels alienated and oppressed by the government.

McCargo is pessimistic about the possibilities: “I feel the greater mainstreaming of the clamour for Buddhism to become a national religion is an ominous sign.”

Dhammakaya and the supreme patriarch

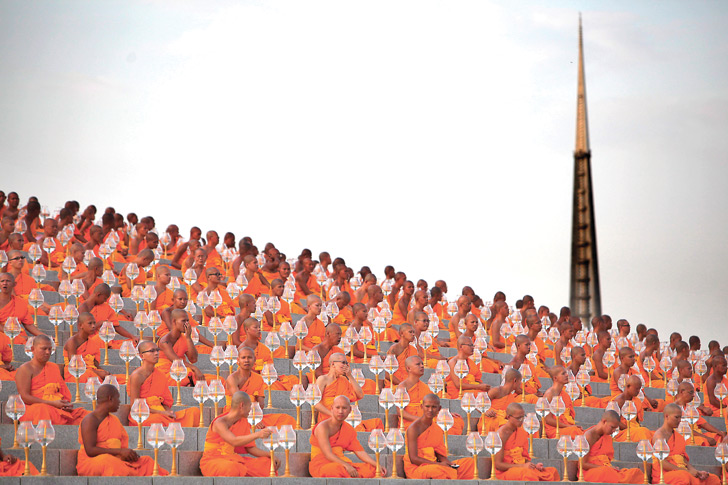

Based in the lavish Wat Dhammakaya in Pathum Thani province, the Dhammakaya movement is the world’s fastest-growing Buddhist sect, with more than 40 branches around the world, including the Dhammakaya Open University in Azusa, California. Since its rise to prominence in the 1990s, it has sparked controversy in its native Thailand for promoting materialism. Many critics have labelled it a secretive, commercially-minded cult that teaches a distorted interpretation of Buddhism and fools people into believing they can buy a better reincarnation. As the Bangkok Post wrote: “[It] teaches that the amount of merit points you get in life depends on the amount of money you donate to Dhammakaya.”

There have been accusations that the Dhammakaya sect is also a power base for the ousted prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra and, therefore, tied to his loyal Redshirt movement, although such claims are highly debatable. Despite its detractors, nobody can doubt the importance of the Dhammakaya sect in Thailand, and it now appears that its influence extends all the way up the Buddhist hierarchy.

In 2013, Thailand’s late supreme patriarch – the country’s most senior monk – passed away at the age of 100 and was cremated last December. On January 14, the Sangha Supreme Council – the highest Buddhist body in the country – nominated Maha Ratchamangalacharn, a controversial 90-year-old abbot of Wat Pak Nam Phasi Charoen, to ascend to the top role.

The frontrunner for the post for many months, there has been intense opposition to Ratchamangalacharn’s nomination because of his purported ties with the Wat Dhammakaya sect and his alleged tax evasion. Sulak Sivaraksa, a social critic, told the Bangkok Post that if Ratchamangalacharn does become the supreme patriarch “a dark era of Buddhism in Thailand will come”.

The nomination must now go to the government for formal acceptance. However, there is no guarantee the military junta will accept the decision, especially as Ratchamangalacharn is alleged to have links to the opposition Redshirt movement.

A petition, signed by 1.7 million people, was submitted to Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha last month, asking him to ignore the nomination and instead give King Bhumibol Adulyadej the sole power to appoint a different supreme patriarch.

The Constitution

After the coup of May 2014, Thailand’s constitution was rescinded and the military junta formed the longwinded National Legislative Assembly and Constitution Drafting Committee to write a new one. However, that charter was rejected in September 2015 by the National Reform Council – a legislative body also set up in 2014 by the military – with 135 lawmakers voting against it and only 105 in favour.

The rejected draft included provisions for the establishment of a committee made up of senior officers from the country’s military, along with a number of ‘experts’, that would be able to intervene in politics at times of “national crisis”. It would have also changed the country’s upper house so that it was only partially elected, with just 123 members out of 200 elected by voters, a move many commentators criticised as undemocratic.

Following the rejection of the proposals, a new body was formed to draft yet another constitution, which is expected to be completed by April. The possibility of a democratic election has been pushed back to at least 2017.