Editor’s note: When we think of the Khmer Rouge, we don’t normally think of a roomful of technicians feverishly cutting clips together in a Phnom Penh film lab. But for Oum Prum, one of the men recruited by the regime to film the brutal rebirth of Cambodia under Pol Pot’s forces, this was the lens through which he viewed the darkest chapter in the Kingdom’s past. His memories of filming the fall of Phnom Penh and the Khmer Rouge’s bloody efforts to rebuild a shattered Cambodia shine new light on a regime desperate not just to craft a new nation, but a new people inspired by acts of wordless self-sacrifice – regardless of the human cost. Now, for the first time, you can read his story online.

OP leans back on his sofa in his Phnom Penh studio. “I was eight years old when I held my first gun, nine when I held my first camera,” he says. OP is short for Oum Prum, the name the Khmer Rouge gave him. Oum means “powerful” and Prum is the four-headed god that smiles from the towers of Cambodia’s most enigmatic temples.

A film producer and real estate owner, the 46-year-old owns several luxurious villas and cars and looks back on an extraordinarily successful life. But that’s all he’s really got in common with your standard movie producer.

Born in Kompong Cham province, he was recruited by the Khmer Rouge in 1970.

For six months he was trained as a stills photographer by North Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge cadres and quickly went on to become a motion picture cameraman.

“There were about 20 students for hands-on training,”he said. “We used black and white Orwo film from East Germany. At the time you still had to wind up the Bolex cameras. We didn’t have a light metre and worked out the aperture by holding out our hand and, according to the light reflection on our wrists, guessed the f-stop.”

After four months’ training, OP’s team and nine others were sent to the frontline. It was 1971, almost a year after General Lon Nol launched his coup and ousted Prince Sihanouk. For four years, OP filmed battles between the Khmer Rouge and government troops, and later the Vietnamese.

“It was fun to go, exciting. I didn’t know how dangerous it really was, but today I realised it was scary. I am lucky to be alive. The KR told us: ‘They shoot us, we shoot them, and that’s how you capture it on film. In the left hand you hold the gun, in the other you hold the camera. If you are not shooting with the camera, you are shooting with the gun’.”

OP claims to have witnessed more than 20 battles between Khmer Rouge troops and those of Lon Nol. Ambushes on the Mekong were some of his favourites. “They would transport goods to Kratie. We had advance knowledge of battle positions and went there ahead of the battle and set up everything.”

“In the left hand you hold the gun, in the other you hold the camera. If you are not shooting with the camera, you are shooting with the gun”

An unnamed Khmer Rouge instructor

In March 1975 he arrived in a besieged Phnom Penh. “We didn’t know what day it was, but I remember that I arrived at 3pm at a spot where the Japanese Bridge is today. We came by boat. There were many Khmer Rouge spies in civilian clothes. I hid the camera and went back to the jungle.

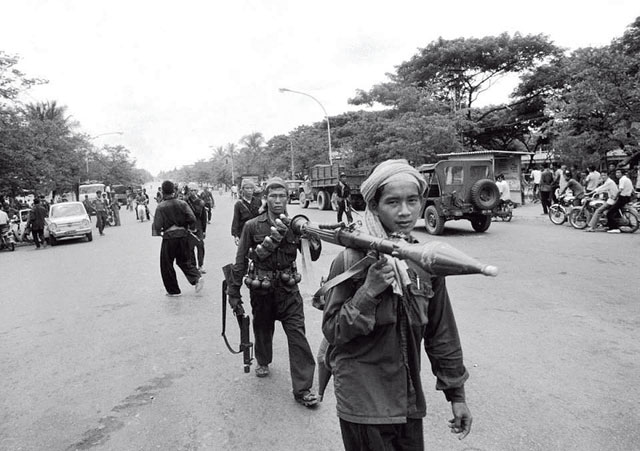

“In April we came back to Phnom Penh. Everyone wore the Khmer Rouge uniform, all black and the Khmer Rouge sandals. Then we shot the fall of Phnom Penh. We shot how they chased people out of the city. It was very exciting.”

OP had been ordered to deliver all his footage to the Chinese. “There was no way I could keep any. I had to sign for all the rolls they gave me, so I had to return everything. And they had to be developed correctly. ‘Make sure you get the picture,’ they told us. ‘If you don’t have the picture, you are in trouble.’ They would accept no excuses. If you don’t get the images, don’t show up.”

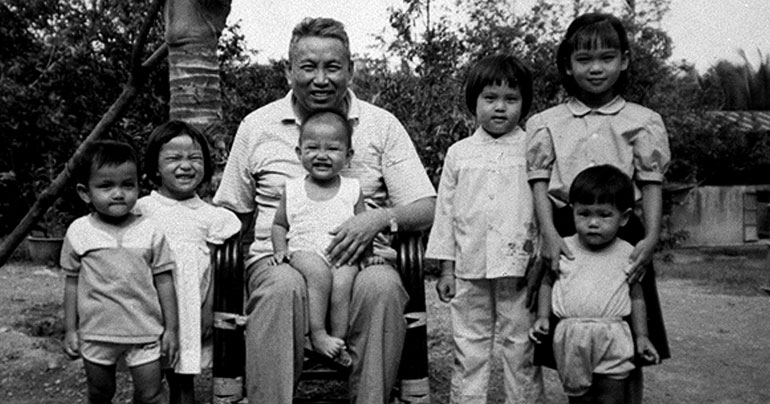

In 1976, after Phnom Penh had been virtually emptied of its population, OP attended a party rally at the Olympic Stadium. It was packed, and OP sat in front, 30 metres from the podium where the leaders were sitting. It was the first time he learned that the brotherly relationship of the Khmer Rouge with North Vietnam was no more. It was also the first time he saw Pol Pot, Brother Number One.

Later he shot Khmer Rouge propaganda films, documenting a wide range of topics from the harvest season, dam building and technology to industries and railway development. The films were shown in villages throughout Cambodia. “When we went to the villages the faces of the people looked very sad, but we couldn’t talk to them, we had to keep our distance.” He says he had heard of killings by the KR, but says he never witnessed any.

After 1975, Chinese advisers arrived in Cambodia and set up a film lab in Phnom Penh. Most of the time OP worked in the lab developing films. “It was so peaceful. We were only allowed to walk from our sleeping quarters to the place where we worked. There was no bank, no cyclo, no nothing. The KR had cooking units and you had to take your own spoon and plate. They cooked in one spot and we had to go there and pick up the food. No need to talk, finish your meal quickly, clean the plate, go back to your room.

“We were many people, men and women working together at the lab. My leader was called Mr Sokorn. One day he disappeared and shortly afterwards the Vietnamese came. Nobody had warned us. We changed our clothes and went our own way back to our homes. I haven’t seen anybody from my team since. Everyone disappeared. All gone.”

When OP got home, he found that most of his family were still alive except for a brother and sister, who are missing to this day. With no work available, he decided to go to the Thai border and look for opportunities to find food and make money.

“We reached a camp, I believe it was Site 2, where there were a lot of NGOs and foreigners. I just registered my name, told them some things about my background and then they processed us. After I arrived in the other country I asked people: ‘Is this Germany? France?’ They told me: ‘No, this is America’.”

It was 1980 and OP had arrived in Oakland, California. “I was homesick at first. I wasn’t used to so many buildings and cities, I was used to the jungle.”

After school he got a job in a film equipment rental shop in San Francisco. “They had lots of cameras and I knew how they worked. I cleaned the equipment and they paid me $2.50 an hour.” A year later he was promoted and put in charge of the rental department. He stayed for three years, saved some money and returned to Cambodia in 1988.

In Phnom Penh he headed for the junction of Monivong and Street 222, where he started digging about a metre from the corner. “I had buried some Khmer feature films in a metal canister there. I sent the films to my brother and wife in the US and told them to show them to Cambodian expats in the US for money.” He had about eight to ten films from the early 1970s, which he transferred to VHS and sold for $25.

“With only $20,000 in 1990 I could have bought half of Phnom Penh”

Former Khmer Rouge filmmaker Oum Prum

He then moved on to shoot films in Cambodia, mostly love stories with titles such as Missing Love and That Is Your Mother, which he sent to America. He subsequently used the profits to buy up land in Cambodia. “I sold one hectare of land for $250 and the people grew corn for me. I gave them 60% and kept 40%. Some of the land I sold. That’s how I made my fortune. With only $20,000 in 1990 I could have bought half of Phnom Penh.”

He read an article about Jim Jannard’s RED One, one of the first digital movie cameras to record images with a resolution up to 2.5 times higher than 35mm film, which cost only $17,500.

“When Jannard wrote that his digital camera functioned like a film camera, I e-mailed him and deposited $15,000 with his company. Even before he launched the camera I understood what he was talking about and knew he could become a ‘leader of the revolution’. I wanted to be part of that technological revolution.

“When I read the word RED in connection with the camera, I remembered the Khmer Rouge. They used red for everything: the name, the flag, red, red, red. I guess I am addicted to the colour red.”