Cambodia’s struggle for self-assertion is a balancing act, with parallels to the 1960s when Prince Sihanouk tried to safeguard his nation’s neutrality in the Vietnam War

By Dr Markus Karbaum

The needle of Cambodia’s foreign policy compass does not point in one true direction. Given that it is located in a region with strong nationalist sentiments and weak collective security mechanisms, this can make for a rather anarchic neighbourhood. As such, Cambodia’s sovereignty often appears as a struggle for self-assertion, especially when bigger conflicts throw the region into turmoil.

This brief analysis of the Kingdom’s geopolitical outlook can easily be applied to either the Vietnam War period or the present day. Despite the region being quite a way from warfare, East and Southeast Asia are appearing less comfortable as neighbours than at any other time in the past 30 years: Multiple confrontations have caused quite a stir in the ‘spaghetti bowl’ that is bilateral relations.

Nestled in the centre of said bowl is China, an ambitious giant that looks set to become the world’s second superpower. To underline its regional claims, it has hurtled into diverse conflicts: with Japan over the Senkaku and Diaoyu islands; with half of Southeast Asia over territorial claims in the South China Sea; and in a broader context the ‘red dragon’ is determined to replace the US as top dog in the West Pacific, which affects US allies Taiwan and the Philippines significantly.

Among these rivalries, China’s conflict with Vietnam has become the most intense. Both states claim ownership of the Spratly and Paracel islands, resource-rich fishing grounds in the South China Sea. This puts Cambodia in a rather awkward position.

Even though Hanoi ended its occupation of Cambodia – following its removal of the Khmer Rouge – in 1989, the Vietnamese influence is still enormous, not least due to its instalment of the current Cambodian government, which has been ruling the country for the past three-and-a-half decades. Even though Prime Minister Hun Sen has overseen Cambodia’s emancipation from its neighbour, the government’s relations with Vietnam are in relatively good order.

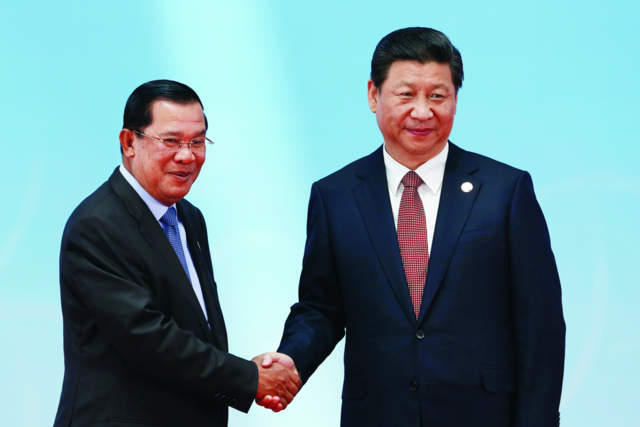

However, in terms of the economic and political support necessary for Hun Sen’s ruling Cambodian People’s Party to stay in power, it is China that holds all the aces, rather than Vietnam. In recent years, multibillion-dollar investments, loans and other financial support has washed in from Beijing to Phnom Penh. But it came with conditions.

Within Asean – in which the only decisions made are unanimous ones – it is an open secret that Cambodia has been advised by China to prevent a joint approach on issues relating to the South China Sea. Unsurprisingly, this has put a strain on relations between Cambodia and in regional neighbours.

The recent attacks against Chinese minorities and businesses in Vietnam must have set off alarm bells in Cambodia. As long as this conflict between Phnom Penh’s two closest allies does not escalate, it should be possible to pull off a delicate balancing act.

On one hand, Vietnam expects maximum solidarity on military issues: Due to its very narrow east-west landscape, Vietnam postulates that its security depends on the hinterland; that only the use of Laotian and Cambodian territory enables a deeper space that is indispensible in modern military defence strategies. A strong Chinese influence in Cambodia seriously endangers this idea.

On the other hand, China needs Cambodian support for its territorial claims in the region; some might even call it a ‘Chinese agent’ within Asean. So far, Chinese and Vietnamese expectations towards Cambodia have been bearable, but they are likely to increase if their conflict intensifies. The Kingdom will almost certainly be roped into the situation – although it can hardly take sides for or against one of its allies. Prince Sihanouk’s policy of neutrality in the 1960s can serve as a role model, although a unilateral orientation towards China, as suggested by opposition leader Sam Rainsy a few months ago, would result in grave consequences at best – no country can openly shun its neighbour.

Given this dilemma, the Cambodian government would be well advised to maintain good relations with other states. This makes the recent border conflicts with Thailand particularly concerning, although military links with the US – proven by the annual Angkor Sentinel exercises – and increasing development cooperation with the EU and Japan are important reinsurances. However, Cambodia’s human rights record, flawed elections and rampant corruption are serious issues that put a strain on relations with any democratic state.

Therefore, the key to Cambodia’s self-assertion lies in its own domestic politics, but the government struggles to find solutions that ensure the country’s independence from other nations, as well as financial independence from aid and assistance. While the necessary reforms remain out of sight, Cambodia is giving itself a hard time in terms of foreign policy.

Keep reading:

“Second fiddle” – Kem Sokha has been a prominent human rights activist and head of his own party, but will his biggest challenge be as second-in-command to his former political rival?