Uncle Chet's Meat Supply

Amid its rapidly modernising and increasingly sanitised landscape, only small pockets of old Bangkok survive today. Photographer Marcel Mayer shadows Uncle Chet, a pig slaughterer in the city's historic Chinatown for decades, who is one such living relic of a bygone era

Words and images by Marcel Mayer

As night falls, a pick-up truck pulls into the backyards of Plaeng Nam Markets in Bangkok’s Chinatown – the former commercial centre and culinary melting pot of the city.

A skinny, wiry old man steps out of the vehicle. Walking around to the back of the truck, he begins to haul large pig carcases to deliver them to the main supplier of meat to Chinatown’s small food stalls and restaurants around the marketplace.

68-year-old pig slaughterer Uncle Chet, who comes from the city’s working-class, dockside Klong Toey area, has been delivering pigs to the market each night since the early 1970s.

“Times are changing rapidly in Bangkok, but my work and this place haven’t really changed that much,” Uncle Chet says, as he lifts the raw pig flesh out of his pick-up, his arms notably muscular from five decades of conditioning.

Each pig half weighs about 45kg. It is hard work and requires all my strength, but it also keeps me fit

Uncle Chet

Plaeng Nam Market is famous for its numerous traditional markets and endless lines of little shops.

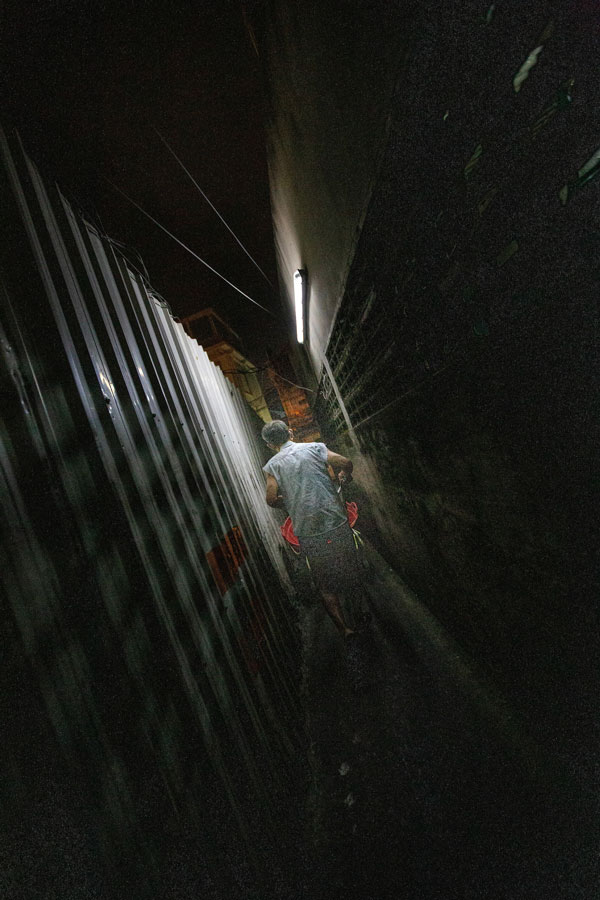

Around 10pm, as Chinatown’s night markets empty, restaurants serve their final patrons and the tourists leave to and head back to their hotels, things grow quiet deep in the backstreets of Chinatown.

At this time, only a couple of vendors and workers have started their night shift at Plaeng Nam Markets, with most instead arriving in the early hours of the morning to do business.

But this is the time when Uncle Chet arrives, each night, at the same spot to deliver his meats.

“I do this job everyday, whatever the weather is,” Uncle Chet says. “Only on very special occasions like Loi Krathong I make an exception and pray to Buddha for a good life,” he explains, referring to Loi Krathong, otherwise known as “The Light Festival” – celebrated annually throughout Thailand and in nearby countries.

Plaeng Nam is nestled deep within the buzzing restaurants and street stalls in the heart of Bangkok’s Chinatown. The street itself is only a few hundred metres long, and in the past locals have used it as a dumping ground for their discarded waste as it is situated close to a nearby wet market. This, historically, earned it the nickname Trok Pacha Ma Nao (loosely translated to ‘rotten dog alley’) among locals.

Settled in the 1780s by Chinese merchants, the area is famous for its numerous traditional markets and endless lines of little shops that form an alley of exotic smells and flashing neon signs. Plumes of smoke blend together a clutter of merchants, locals and tourists, all hustling through the narrow streets.

Today, life in Chinatown’s small backstreets hasn’t changed with the same speed as Bangkok’s central business district and elsewhere in the city, with its ever growing number of condominiums and luxury developments. It remains one of the few pockets of the city to retain a historic and vibrant community feel, with low-rise shophouses still aplenty and skyscrapers hard to come by.

Its lack of connection to Bangkok’s vast rail network was perhaps Chinatown’s saving grace for decades, but with the arrival in July 2019 of a new MRT train line extension to Wat Mangkon, things are likely to soon change as the inevitable charge of ‘progress’ proves impossible to halt.

Plaeng Nam is the name of a small street that intersects with Charoen Krung to Yaowarat Road in the heart of Bangkok`s Chinatown. It is close to the Wat Mangkon, also known as Wat Leng Noei Yi, the largest and most important Chinese temple in the city.

Despite being 68 and having lost his left eye in a car accident as a younger man, Uncle Chet shows no signs of slowing down. It will take him eight to ten trips to deliver all his pigs, pulling his heavy cart through the narrow and congested walkways of Plaeng Nam into the old market hall.

He unloads his slaughtered and quartered pigs piece-by-piece, placing everything on the bare ground. Between unloading pig carcasses he stoically describes the arduous work he has persevered through for five decades.

“Each pig half weighs about 45kg. It is hard work and requires all my strength, but it also keeps me fit,” Uncle Chet says, throwing a pig side onto a plastic tarp in front of the butchers stall.

Today there are small two-story shophouses in the area filled with eateries offering dishes such as noodles, pork stomach and duck porridge, shark fin and bird`s nest soup.

The offal is then put on the butcher’s table and will be processed directly. For the rest of the night, the butcher processes the pork to sell to the chefs or vendors of the surrounding street food stalls in Chinatown.

I will continue as long as I am able to do it according to my healthy constitution and the rise of mechanisation

Uncle Chet

The street food environment in Bangkok is diverse and almost unparalleled worldwide in its depth and quality. It holds a long tradition in Thai society and is part of everyday life across all social classes. These characteristics have made Bangkok one of the world’s top street food cities in the world and a culinary tourist destination.

Thailand has the biggest pork meat industry in ASEAN, with over 22 million pigs and 1.2 million sows consumed every year.

But under pressure from the Thai government’s crack down on the city’s street food culture, the rise of large-scale meat production industries in Thailand, and ever more stringent sanitation regulations, small meat suppliers like Uncle Chet are playing an increasingly marginal role in city life.

But Uncle Chet himself seems unfazed by Thailand’s rapidly changing food industry, chuckling when asked how long he plans to continue his work.

“As long as I am able to do it according to my healthy constitution and the rise of mechanisation,” he says.