Wanpen Pajai is currently staying in a two-week government quarantine on the outskirts of Bangkok. She will be posting about the experience on her Twitter account.

State quarantine, being stuck in a hotel room for fourteen days, sits in that unique spot somewhere along the spectrum between a paid-for vacation and short-term prison.

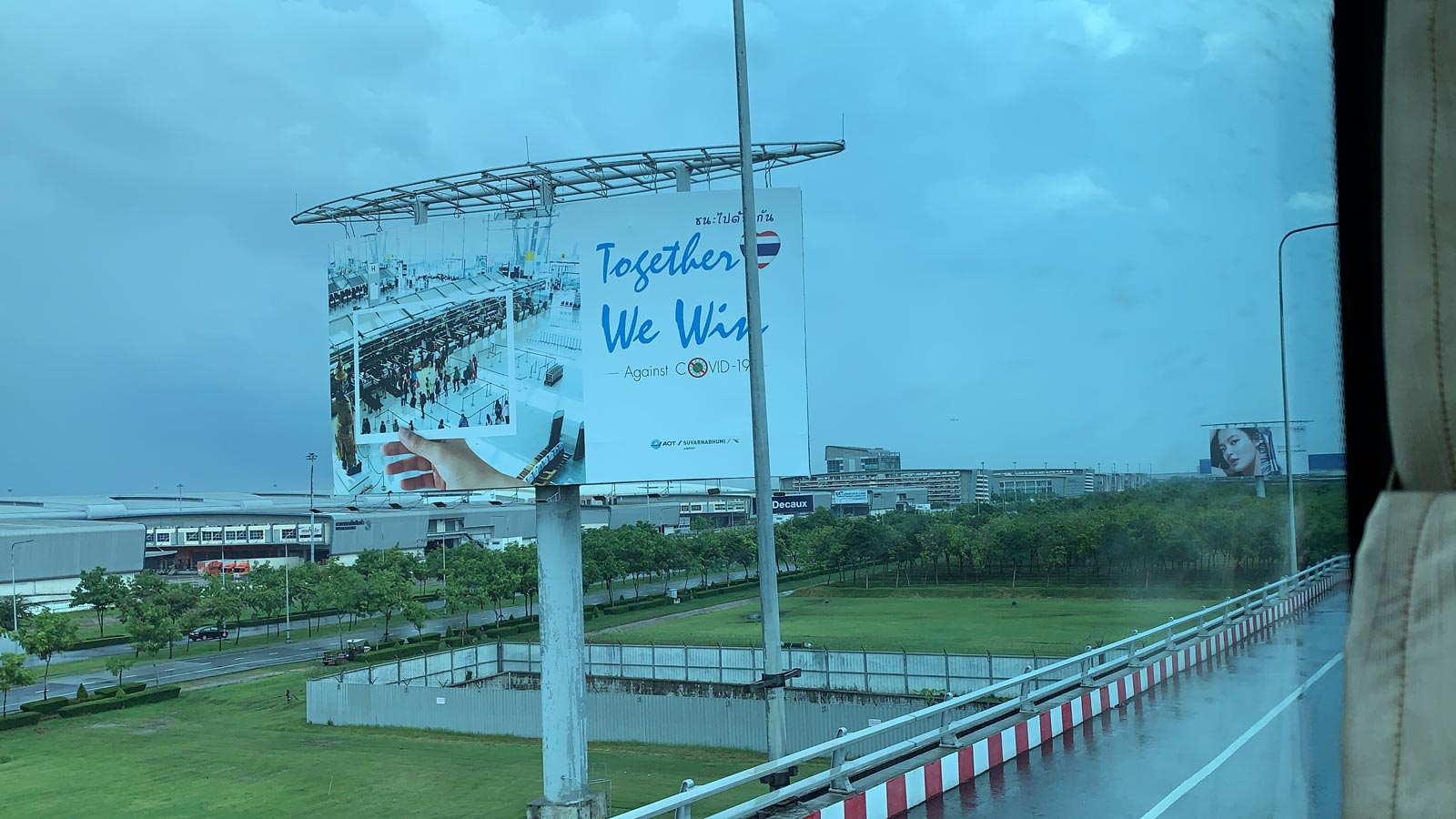

Since April, Thailand has closed its borders and banned international passenger flights to reduce the spread of Covid-19. Thai nationals, and recently non-Thai nationals with work permits, could travel back if given a spot by the embassy and they agreed to undergo state quarantine once in the country.

Flying from Amsterdam in mid-July, Schiphol Airport was relatively busy with departures and arrivals, indicating that air travel during the pandemic had settled in as the “new normal” – in the Netherlands at least.

Thai passengers from all over Europe – from Finland to Switzerland – had converged on the Dutch capital for one of the few running flights to the kingdom, travelling together to Thailand despite the lofty hurdles to jump before arriving at their homes. Four months into the travelling measures adopted by Thailand, citizens knew what to expect of this journey and the state quarantine that loomed ahead.

To travel back on the state-organised flight, a passenger was required to have the fit-to-fly health certificate, a letter from the Thai embassy, and a signed letter showing consent to state quarantine. For state quarantine offered to Thai nationals, the government provides room and board for 14 days, all costs covered. Non-Thai nationals – along with Thai nationals that choose to – have to attend alternative state quarantine in which they pay independently.

With all the seats occupied, social distancing was not an option on the plane. The KLM flight stopped at Bangkok first, dropping off 157 passengers, 139 of which were Thai nationals, before continuing on to the Indonesian capital Jakarta.

“If we were to get Covid, it would be on the plane,” Sulee Moonngeon, a passenger on the flight, told a Globe reporter seated near her.

Sulee got married at the end of last year to her Norwegian partner and has come back to Thailand to visit her parents and take her daughter back to Norway with her. “I really want to be with her, she’s 15 years old and growing into a woman. I haven’t been able to [go home] with the pandemic, so she’s been with her grandparents.”

There’s no ghosts here, there are also monks in quarantine here

The moment the plane landed in Bangkok, there was no room for confusion. Passengers had to follow systematic precautionary steps, reminiscent of a lab experiment in some dystopian movie, as if we were some special, but hazardous, species awaiting inspection. In neat rows of chairs and lines of passengers, we were ushered from one stop to the next by government officials covered in hazmat suits.

As we stepped out of Suvarnabhumi’s arrival terminal, we were directed to go to a bus, clueless about where we were headed as it took off.

The hotel – a complex of eight-storey modernist blocks, each different shades of brown in the middle of rice fields and next to a small river – is in Samut Prakan, close to Suvarnabhumi Airport and industrial warehouses. Prior to Covid-19, the hotel catered for large Chinese tour groups looking for a retreat on the outskirts of the city, but with the borders closed, it has partnered with the government to become a quarantine facility – a label few working at the establishment could have conceived just six months ago.

“I haven’t been able to travel home since April. I’ve been here taking care of all the travellers from abroad,” said a hotel staff member, dressed in rain boots and, a hazmat suit, with both a face mask and a face shield on. The look of tiredness in his eyes was evident. “Please cooperate with the rules,” he said, his eyes squinting slightly, probably indicating a smile obscured behind the mask.

He proceeded to repeat the instructions. Check your temperature twice a day. Collect the meal left outside your door three times a day. Join the group chats. Separate the trash.

Sharing small talk with a Thai man in the elevator on the way up to the room, it became apparent that we’d both come from the Netherlands. But unlike me, he didn’t live on land.

“I worked off-shore in the North Sea on an oil and gas drilling rig, but with the Covid situation, I’m travelling back to Thailand,” he said, referring to the Northern European sea that hosts large oil reserves.

The room is a simple one, borderline bland, but quite spacious for one person. Outside the window, the grid of identical rectangular portals across provides a glimpse into the lives of others quarantining. When I arrived, most curtains were drawn, with only an orange silhouette to be seen in the room directly opposite. Its stillness at first made it seem like an orange shirt hung over a chair, but as the sun set, illuminating the room’s interior, it turned out to be a monk meditating peacefully in his room.

“There’s no ghosts here, there are also monks in quarantine here,” texted a staff in the Line group, offering some comfort to a person saying she was concerned about ghosts and was not able to sleep. “Turn on some soft music or Buddhist prayers. It can help you to relax.” Within seconds, other people chimed in and confirmed the calming effect of Buddhist prayers – a soothing reminder that everything will be okay and to be in the present moment.

“It’s nice. I get to relax for a bit and adjust to the transition. It’s a safe zone to make sure we don’t have Covid. I don’t want to come home and potentially spread [Covid] to my family or anyone else,” said Sulee, the woman from the flight.

The cost of state quarantine is covered by the central budget of government ministries. Thailand’s community transmission cases are low, and cases mostly emerge from Thais who repatriate from overseas, indicating that this state quarantine may help to curb the reemergence of Covid-19.

With the economic downturn in Thailand, state quarantine – with a spacious room, good Thai food, and unlimited AC for two weeks – feels like a little oasis for now. But for some, quarantine meant not being able to say their final goodbyes.

His spirit knows that I’m back home. It’s okay, I’ll go pay my respects when I’m out of quarantine

Pailin Seehawong planned to travel back to Thailand from Switzerland to care for her father who was sick, but he passed away on the day she arrived. Stuck in state quarantine, she was not able to attend the funeral.

“[His spirit] knows that I’m back home. It’s okay, I’ll go pay my respects when I’m out of quarantine,” Pailin said, her voice cracking a little. “But with quarantine, at least I know I won’t spread Covid to my family.”

Both Sulee and Pailin shared that the staff along the way, from the embassy to the quarantine facility, have taken good care of them and been helpful.

Stuck in limbo – in which traveling between Europe and Thailand requires a host of paperwork, approval from the embassy, and 14 days of quarantine – means a lot of people have not seen their families for months. Most people understand that this is done to protect Thailand, but when exceptions are allowed, as happened recently with Egyptian soldiers, it enrages people.

The journey home to Thailand from Europe has changed significantly since the onset of the pandemic. But perhaps the best part of any travel, sharing stories and connecting with complete strangers along the journey, remained largely unchanged.

This story is part of the Globe’s collection of personal essays from across Southeast Asia called Tales of the Pandemic. Covering different aspects of life during this unprecedented time in human history, all of these Covid-19 personal essays can be found here. If you’d like to contribute a personal essay of your own, please email your story of roughly 1,000 words to a.mccready@globemediaasia.com.