The power of script

With the rise of the internet age, Southeast Asia is fast embracing change. But within a digital world initially designed for Latin scripts and fonts, the region is still playing catch up to ensure its citizens have equal access to every online feature

Words by Zachary Frye; Images by Ben Mitchell

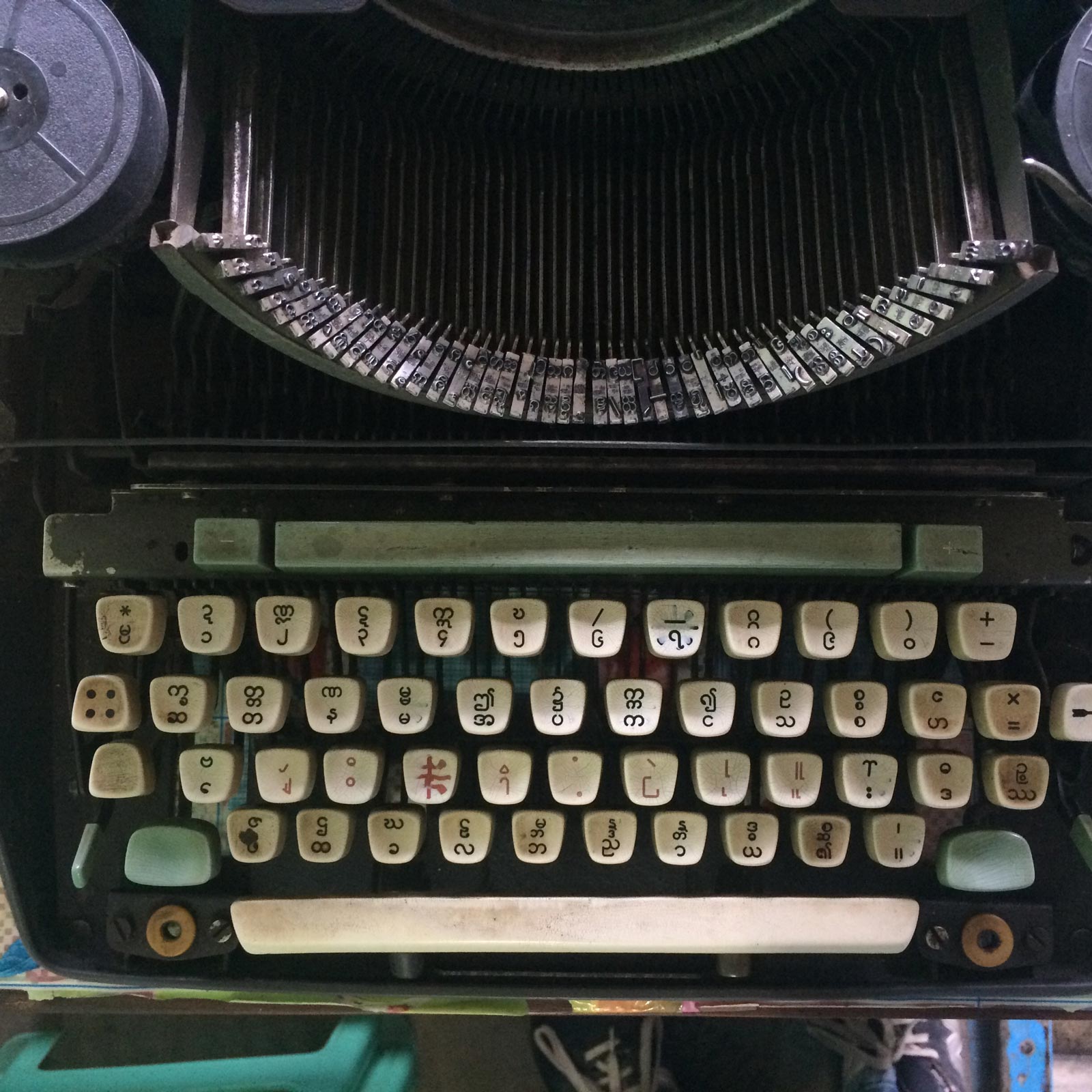

Misplaced symbols. Large squares and rows of bold lines in place of words. An inability to search text on webpages. A few short years ago, this was the norm for internet users reading the Burmese language, even on popular sites like Facebook, Wikipedia or BBC News Myanmar.

Although these problems are getting better, especially after the Burmese government implemented Unicode in 2019 – a standardised text expression system that should make texts legible across platforms – the critical lack of font and script compatibility continues to hold back the digital expression of Myanmar’s citizens.

While these issues are especially pronounced in Myanmar, which only emerged from the digital wilderness after 2011 following decades of economic and cultural isolation under military junta rule, the rest of the Southeast Asia region suffers similar issues – albeit to varying degrees.

But there are some people trying to change that. Ben Mitchell, a typeface designer and Southeast Asian script researcher, is among them.

“If you are a Burmese user on an older operating system, you’re likely going to be familiar with corrupted text. Current versions work better, but the digital infrastructure is nowhere near as sophisticated as for the Latin script,” Mitchell told the Globe. “Companies outside of Southeast Asia often have little understanding of local languages and scripts. This means software, and even operating systems, may not support those languages.”

Yet despite some advancements in technology in recent years, the useability of some Southeast Asian regional scripts on digital platforms significantly lags behind those enjoyed by Western scripts.

“There are several possible ways that things can go wrong [with text on digital platforms],” Mitchell said, diagnosing the problem. “At the font level, designers might not know how particular characters [of a certain language] combine. At the software level, most applications now pass text rendering over to the operating system, but those that don’t throw up all sorts of unexpected errors. At the operating system level, older versions of Windows or Mac OS … support very limited availability for some regional scripts.”

To combat the problem, which impacts digital services in the region, user interfaces, as well as the more fundamental issue of Southeast Asian people being able to adequately express themselves on the internet generally, Mitchell created a company called The Fontpad, which specialises in expanding the availability of digital fonts in the region.

“We want to contribute to the development of good quality digital fonts for Southeast Asian alphabets,” Mitchell explained. “There is currently a lack of nice fonts [especially] for Khmer, Lao, and Burmese and I feel like we can contribute our skills in helping those countries have more typographic choice.”

Internet penetration in Southeast Asia varies significantly by country, but continues to grow at a rapid pace. In Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand, over 80% of the population is online in some form, the highest in the region. But for many rural communities in Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos, however, the internet has not yet arrived, and as of 2019 only 33% of Burmese citizens had access.

But this, inevitably, looks set to change in the coming years as technology becomes more widespread and affordable. And according to a report published last year by Google, Temasek and Bain & Co, online industry in the region is expected to grow by 200% over the next five years.

If you are a Mon person or a Shan person you will be forced to read everything in Burmese. But as type designers, we don’t have to prioritise Burmese at the expense of other languages. That would imply Burmese is somehow more important than minority languages, and I’m not comfortable making that judgment

As the number of digital services and platforms in the region rise, Southeast Asian netizens will increasingly expect them to integrate local scripts seamlessly. But if the technical compatibilities with Southeast Asian scripts are not dealt with, however, it could limit how much local populations are able to interact with these new services and platforms.

In Myanmar, script incompatibility problems still impacts society in big and small ways.

“[It limits] people’s options online, especially if they are not digitally literate to use font converters or browser extensions,” said Aye Min Thant, the Tech4Peace Manager at Phandeeyar, a Yangon-based organisation that supports the country’s technology and innovation ecosystem.

“Educational content is not as accessible; buyers and sellers are not as able to easily communicate with one another. As commerce moves online, companies need to decide which encoding system they will advertise in, or if they will use multiple, thereby creating longer and wordier advertisements that people may not like,” she added, referring to the battle between Unicode and Zawgyi –another typeface in Myanmar created over a decade ago to support Burmese script on the internet.

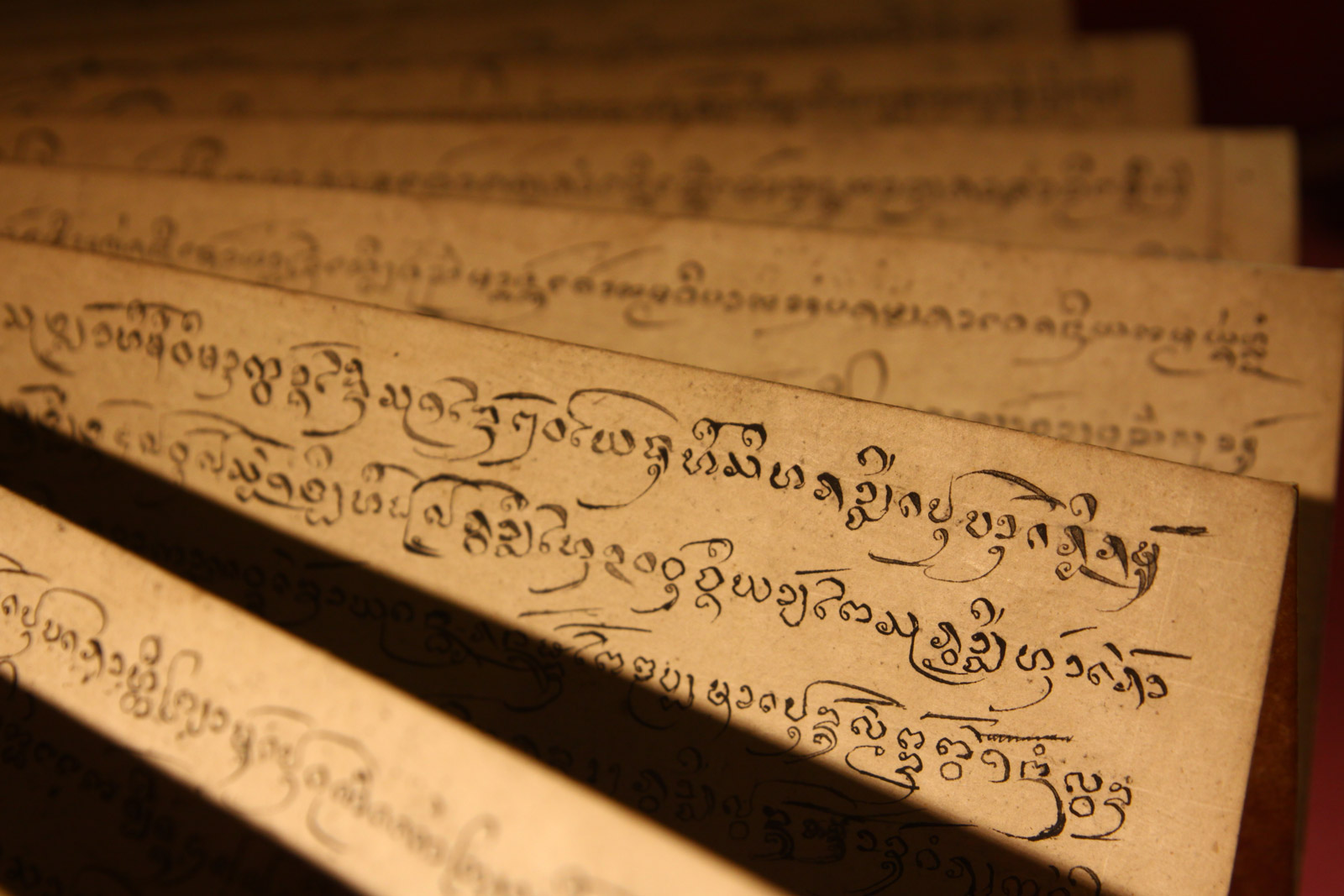

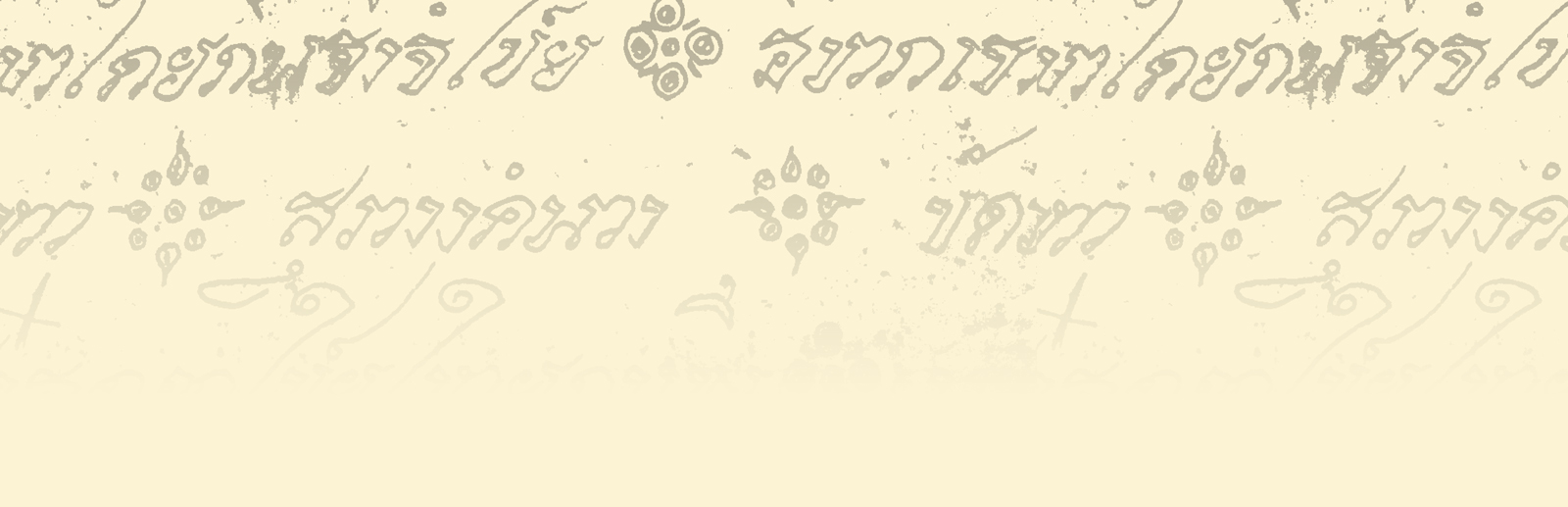

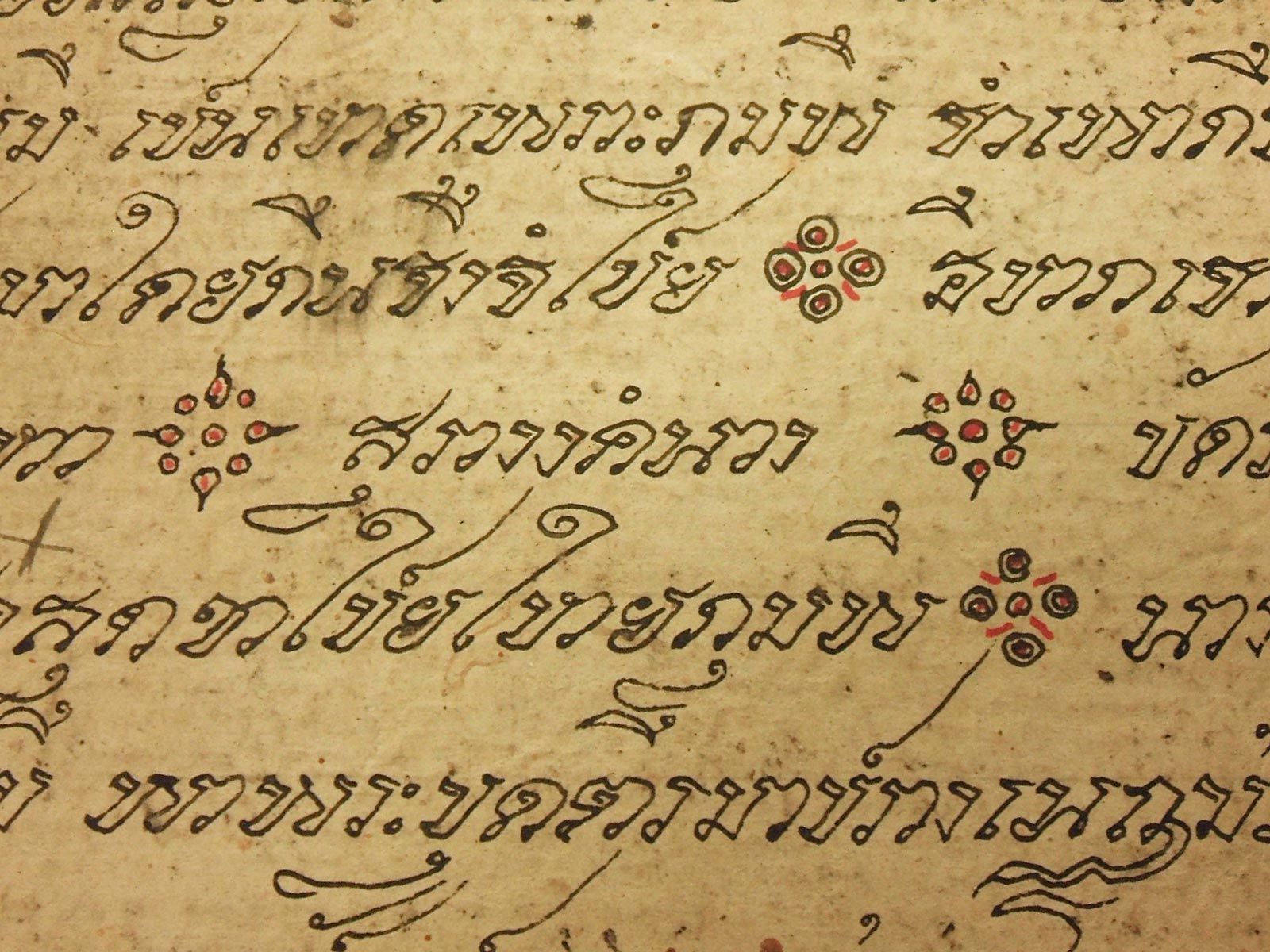

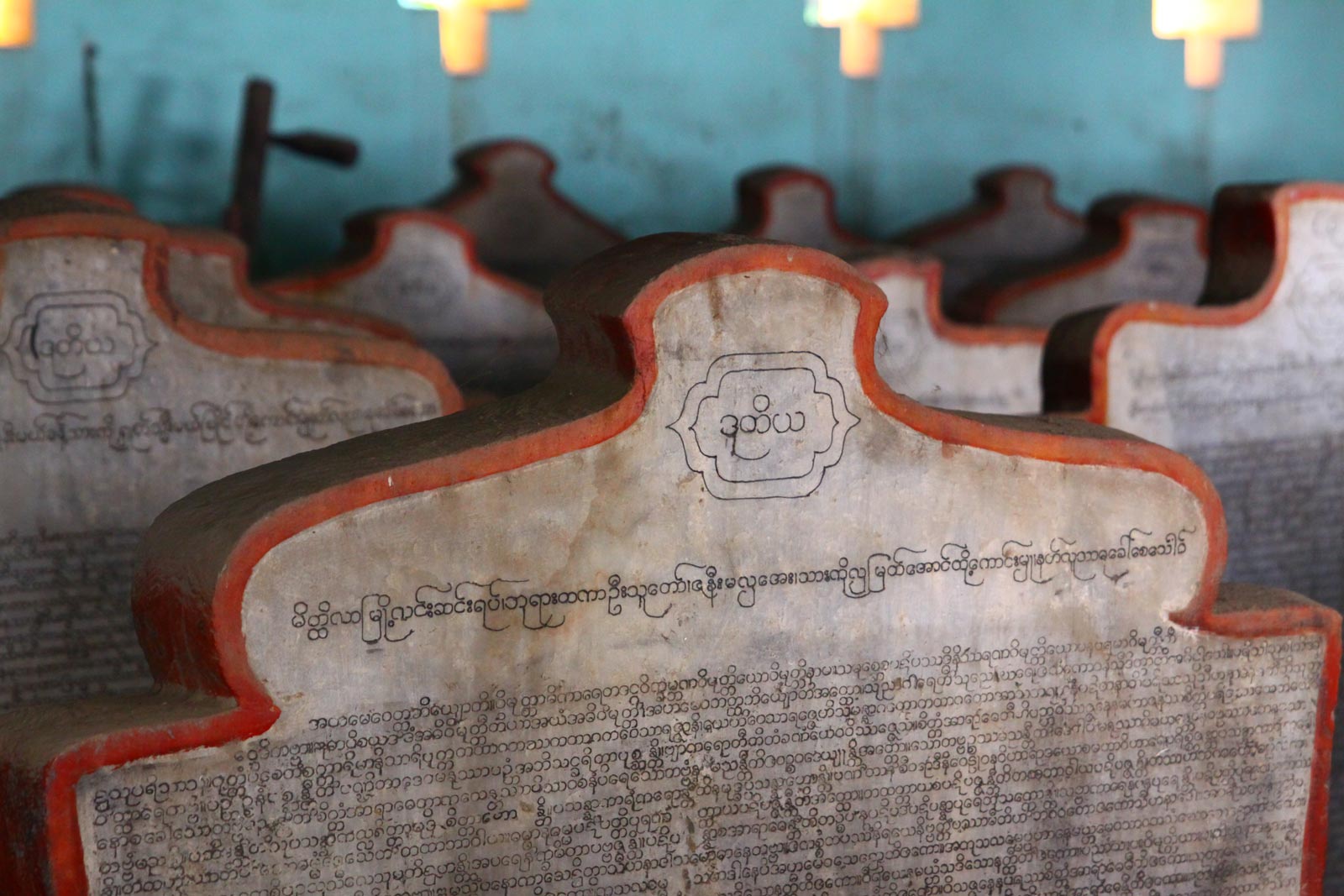

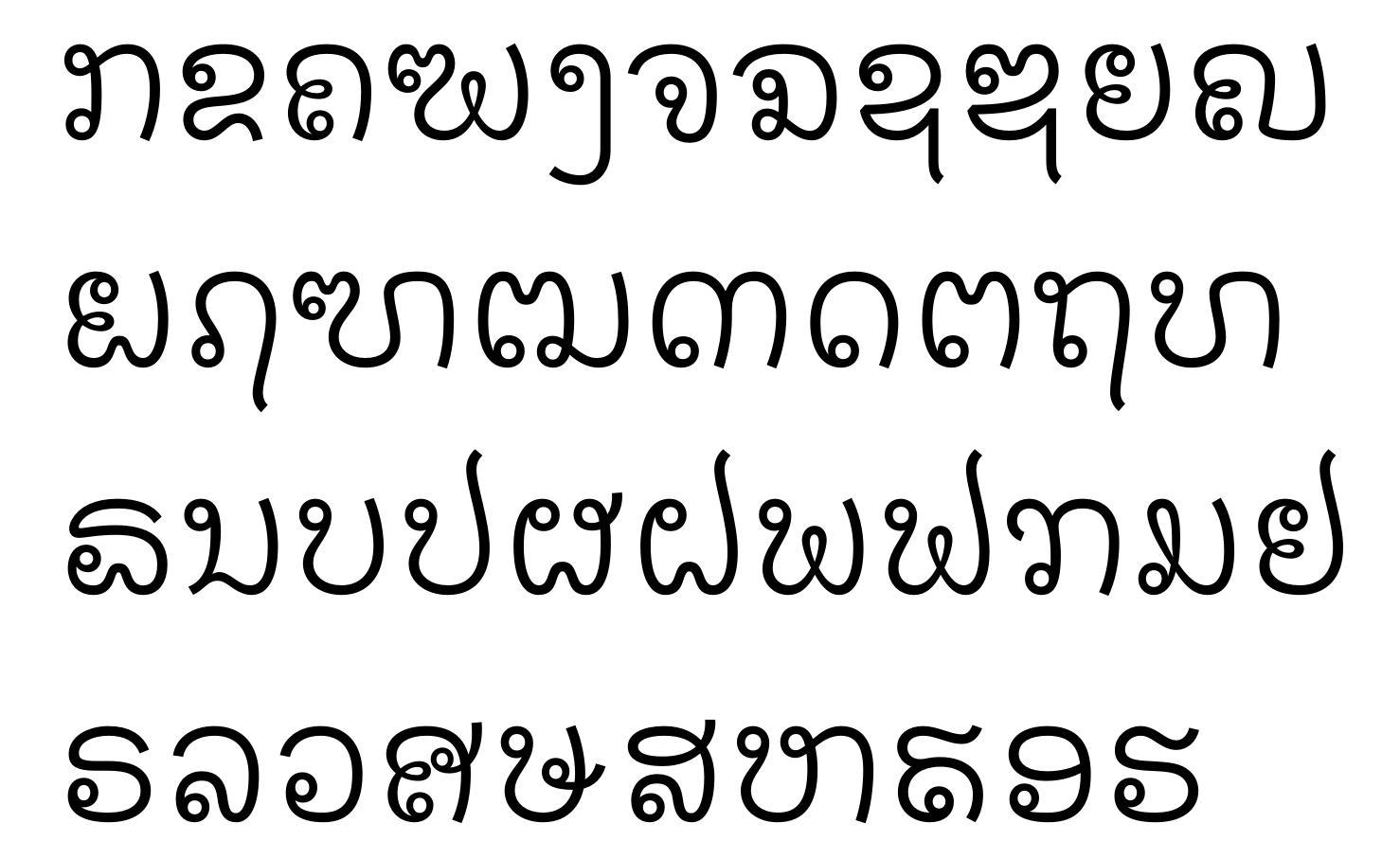

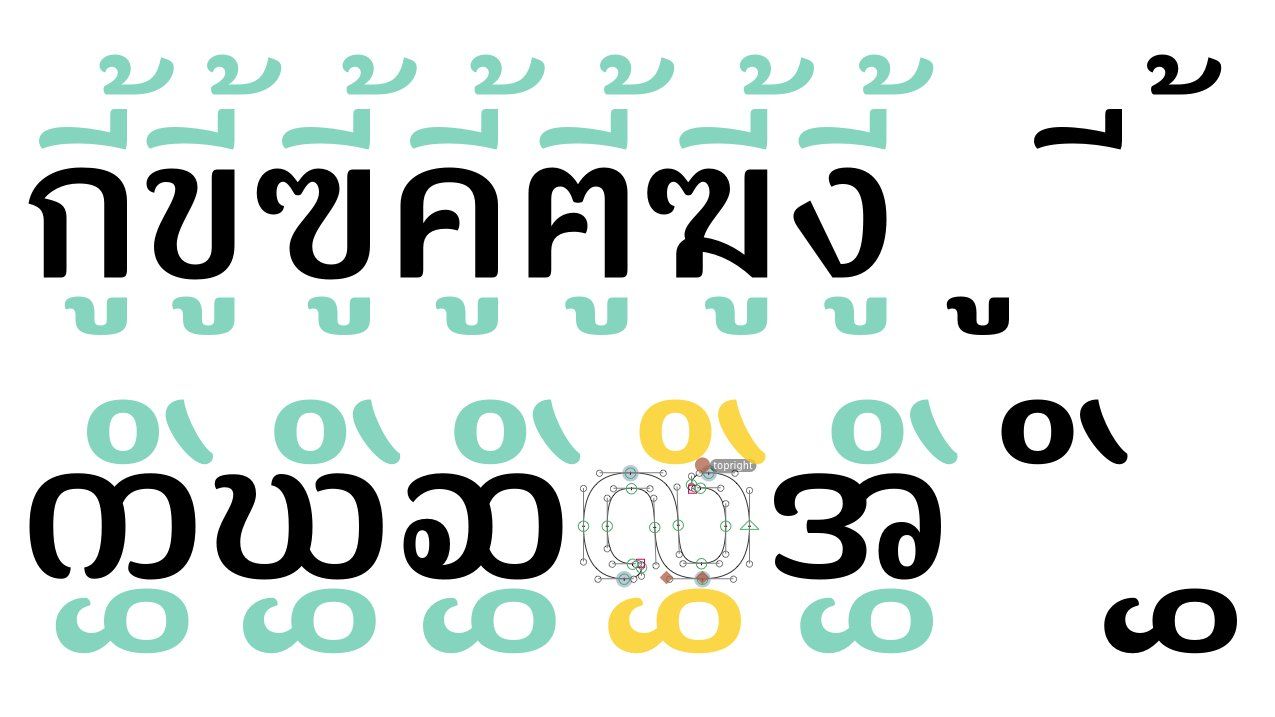

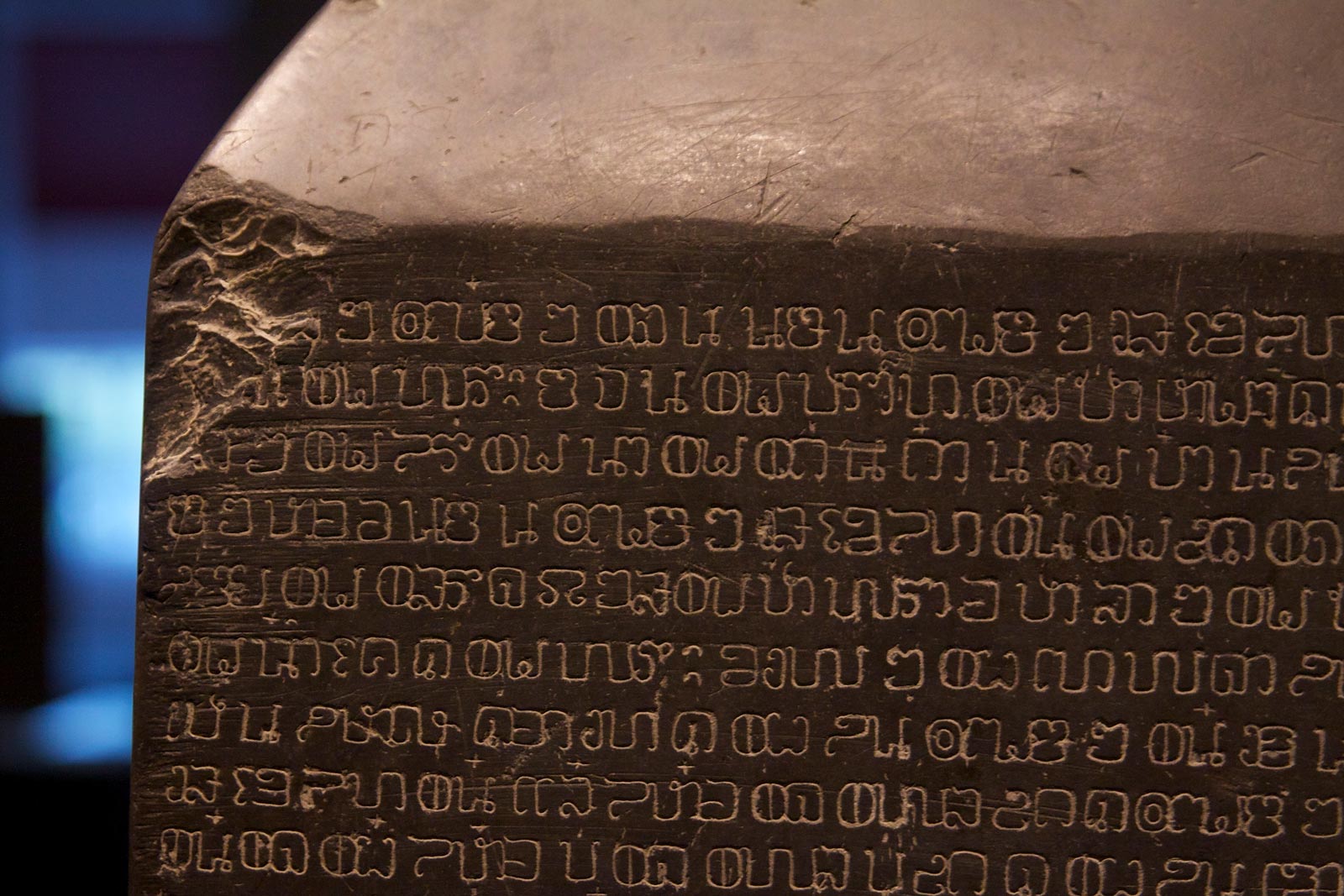

Top: Sometimes, research shows gaps in the digital environment. Here, Ben found that Pali letters for the Lao alphabet were needed to make a Unicode font. Right: Southeast Asian scripts need fine tuning to ensure vowels and other marks are correctly positioned.

Minority group languages in Myanmar, as well as across the region, are even more impacted by these script problems, affecting millions of people across Southeast Asia.

“Minority languages that use different scripts [than the country’s main script] rarely enter the discussion. Cham, Shan, Tham, or Khom on the mainland, or Batak, Baybayin, Buginese or Sundanese in the island nations, for example, often elicit blank stares even in the countries where they’re used,” said Mitchell, referring to some of Southeast Asia’s many minority languages. “That makes it hard to find script experts, which in turn makes it hard for software to support the languages and for designers to make fonts.”

Furthermore, financial disincentive feeds into a general lack of interest in promoting minority languages, often forcing these users to communicate in the majority language’s script, which some may have only a nominal understanding of.

“These [minority] languages are barely supported by any software, operating systems or fonts, meaning users of those scripts have to use the national language if they want to communicate digitally,” Mitchell said.

“Even if the minority languages use the exact same letters as the majority language, we may find nonstandard combinations of characters that devices may not recognise. Work is being carried out to document these languages, but the people who make software need to be part of the discussion even when there’s little commercial incentive.”

An ongoing challenge, however, is the status of minority groups in Southeast Asia. Sometimes, governments might not be interested in pursuing digital integration of minority scripts. Other times, they might be actively trying to undermine these cultures – as is the case in Myanmar, a country that has endured violent conflict between the state and several distinct ethnic groups for decades.

“I have seen over and over again that [increased digitisation] and technology has often had a negative effect – bridges built for economics have facilitated military movement and land grabs,” said Nance Cunningham, a PhD student studying infectious disease in humanitarian contexts and co-author of a popular Burmese-English dictionary.

Mitchell agrees, adding that the lack of minority scripts is more than just a simple inconvenience, but one that can have far reaching implications for minority groups, many of whom are fighting to preserve their own cultural identities.

“Technology has also been responsible for ethnic persecution in Burma; any discussion of improving language handling for languages of Myanmar by extension has to be treated carefully. The over-dominance of Burmese language might be one case in point,” Mitchell added.

“Right now, if you are a Mon person or a Shan person you will be pretty much forced to read everything in Burmese, as opposed to your own language. But as type designers, we don’t have to prioritise Burmese at the expense of other languages in Myanmar. That would imply Burmese is somehow more important than minority languages, and I’m not comfortable making that judgment. We can be more inclusive.”

Overall, software companies are making improvements with integrating regional languages in their products, Mitchell said, but there is still a long way to go for compatibility issues to be solved.

“With software companies, like any big organisation, sometimes sending feedback is like sending something into the void. I know they want to help, but their systems for dealing with these issues still feel a bit disconnected with real users’ needs,” he said.

The problems also seem to be circular, at least in part. In Myanmar, the economy – and many of its people – are disconnected from the global network, reducing the chances that digital companies, many of which are in the West, will give them focus.

“For other international businesses I’ve made custom fonts for in Southeast Asia, they say, well, I can’t pay that much for Burmese because it’s not a strategic country in our overall business strategy,” Mitchell said.

“There is a feeling that Burma isn’t a big priority, which is a difficulty because it’s the most expensive regional script to work with. In Burmese, there is one particular character, ya yit, that might need 30 different shapes for it to fit different syllables. It changes its shape depending on the shape of the syllable … so, there is another layer of extra work that needs to be done. We don’t see that in Latin or even Thai.”

For this reason, online businesses operating in Myanmar still face a mess of different script and font concerns.

“Grab [the ride-hailing and delivery services company] actually needed a Zawgyi version of our font, as they wanted to support older versions of Android,” said Mitchell.

“Much as we hate to recommend it, Zawgyi was the only way to do that on a system that doesn’t know how to render Burmese.”

For Mitchell, the process for creating new fonts in a region with limited digital compatibility, but an abundance of interesting scripts and languages, is a rewarding challenge.

“The thing I like most in my job is that it uses completely different parts of the brain,” he said.

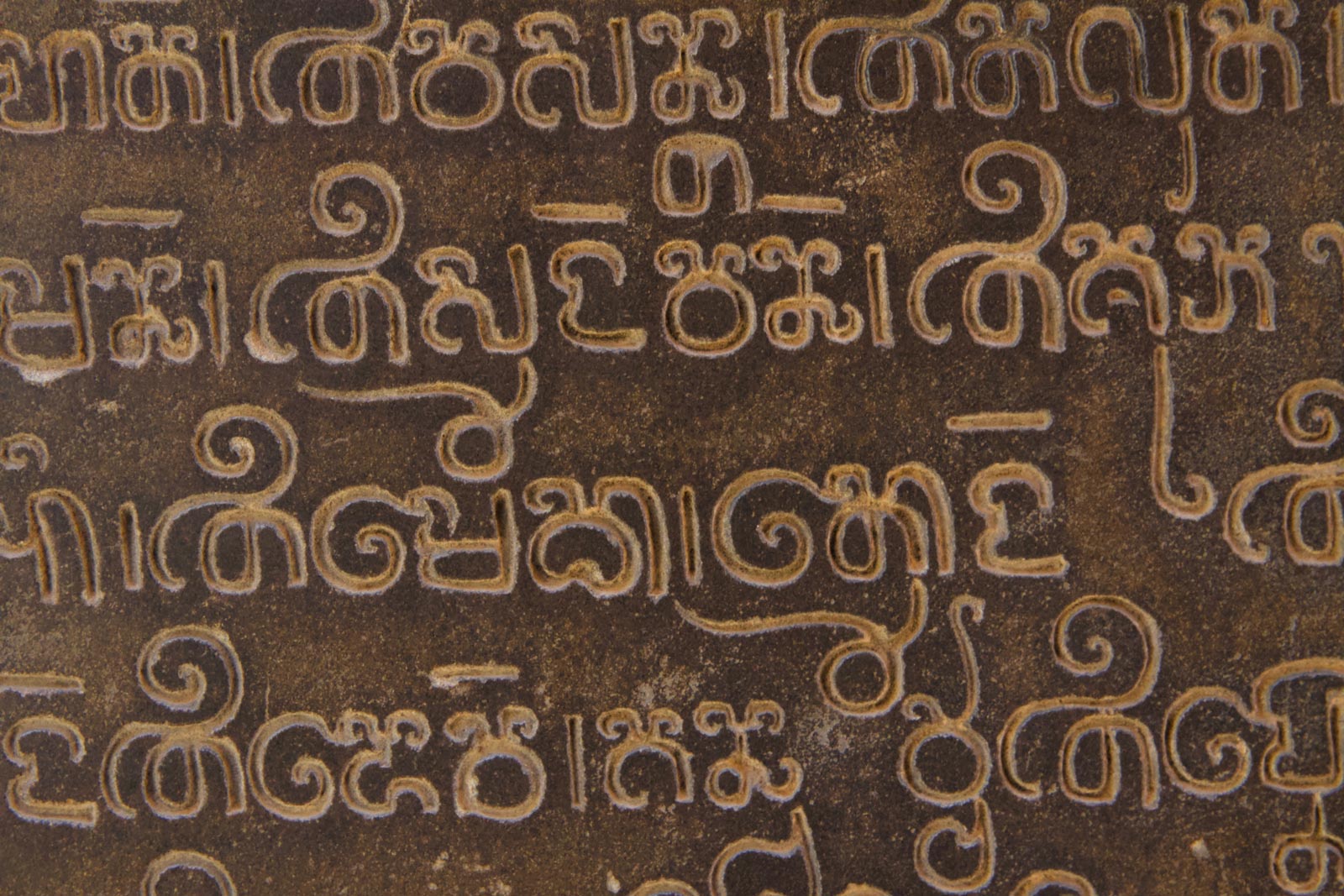

One of the most intriguing questions is how to design a font that coordinates these scripts into a single design without making the Burmese look Khmer or the Lao look Thai. Each script needs to maintain its integrity and identity, but how can we pin down what that means?

“There is definitely an artistic aspect to it, establishing the creative direction for a new design. There is also a logical side, where you are trying to find the most efficient way to fit it all together. There is a research side, digging into the history and language-use of each script, and then there’s the technical side, on how different systems need the fonts to be engineered.”

As for his design technique, Mitchell emphasised the need to focus on originality.

“No two type designers have the same process. I often sketch on paper in the early stages, with a small set of characters, and build from there.”

With that said, creating a new font isn’t always an easy or straightforward process. Not only do designers need to create a distinct character style based on the script, they also need to be careful it doesn’t lose its basic essence.

“One of the most intriguing questions is how to design a font that coordinates these scripts into a single design without making the Burmese look Khmer or the Lao look Thai. Each script needs to maintain its integrity and identity, but how can we pin down what that means?”

As for his favourite script to work with, the most difficult might also be the most satisfying.

“Although I love working on all the Southeast Asian scripts, I especially love Burmese. When everything comes together, and it all clicks into place, you know that you’ve really achieved something,” Mitchell concluded.

But whether working with Burmese, Khmer, or a more obscure minority language, the lack of digital scripts in Southeast Asia looks likely to keep him busy in the years ahead as he looks to welcome more and more people into the global community.