The New Year typically marks a season of optimism and resolutions for positive change.

But what about societies living in fragile democracies or under authoritarian rule? Though we can’t see what the future holds, the political arc of 2023 could be less mysterious if we analyse Southeast Asia’s human rights and democracy records from the past year.

Globally, the number of countries moving toward authoritarianism in 2022 more than doubled the number moving toward democracy, according to the Global State of Democracy Initiative. The democratic decline was especially pronounced in Southeast Asia, a region that has experienced an extreme democratic regression in the past two decades, and countries such as Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam are governed under autocracies without effective rule of law.

The internet also became more restricted, having a negative impact on democracy overall through crackdowns on speech and freedom of association. Governments have shifted authoritarian practices into the digital sphere, arbitrarily arresting and prosecuting a large number of people for their online speech.

In light of this, it comes as no surprise that trust in institutions is fading, people feel ignored and cannot take their freedom or safety for granted. As our world unfolds increasingly in the digital space, our digital rights – widely understood as human rights – must be respected, now more than ever.

A decade ago, the UN Human Rights Council had already established that “the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online, in particular freedom of expression”. However this seems a far cry from the reality for netizens in Southeast Asia, where none of the countries in the region covered by Freedom House in the 2022 Freedom on the Net Report are “free” when it comes to digital rights.

Freedom of speech is the lifeblood of democracy, essential for the discovery and dissemination of political truth, sounding the alarm when authorities commit wrongdoing. However, speaking truth to power is a crime in many Southeast Asian countries. While the internet has become a principal arena in which activists, dissidents, human rights defenders, citizen journalists, independent media and opposition political leaders express their opinions.

The high price of free speech

Freedom on the Net 2022 found last year that global internet freedom declined for the 12th consecutive time. One of the sharpest downgrades worldwide was documented in Myanmar, where internet freedom reached an all-time low, scoring 12/100.

Since the February 2021 coup, the military junta has launched a brutal agenda of repression. In addition to detentions and horrific physical violence, the junta imposed nationwide internet shutdowns, blocking access to social media and messaging platforms. The military has killed at least 2,400 people since the coup and arrested more than 16,000. It has also formally executed at least four individuals and sentenced countless others to death.

In all of the Southeast Asian countries covered by Freedom on the Net report, authorities arrested people for discussing political, religious or social topics online.

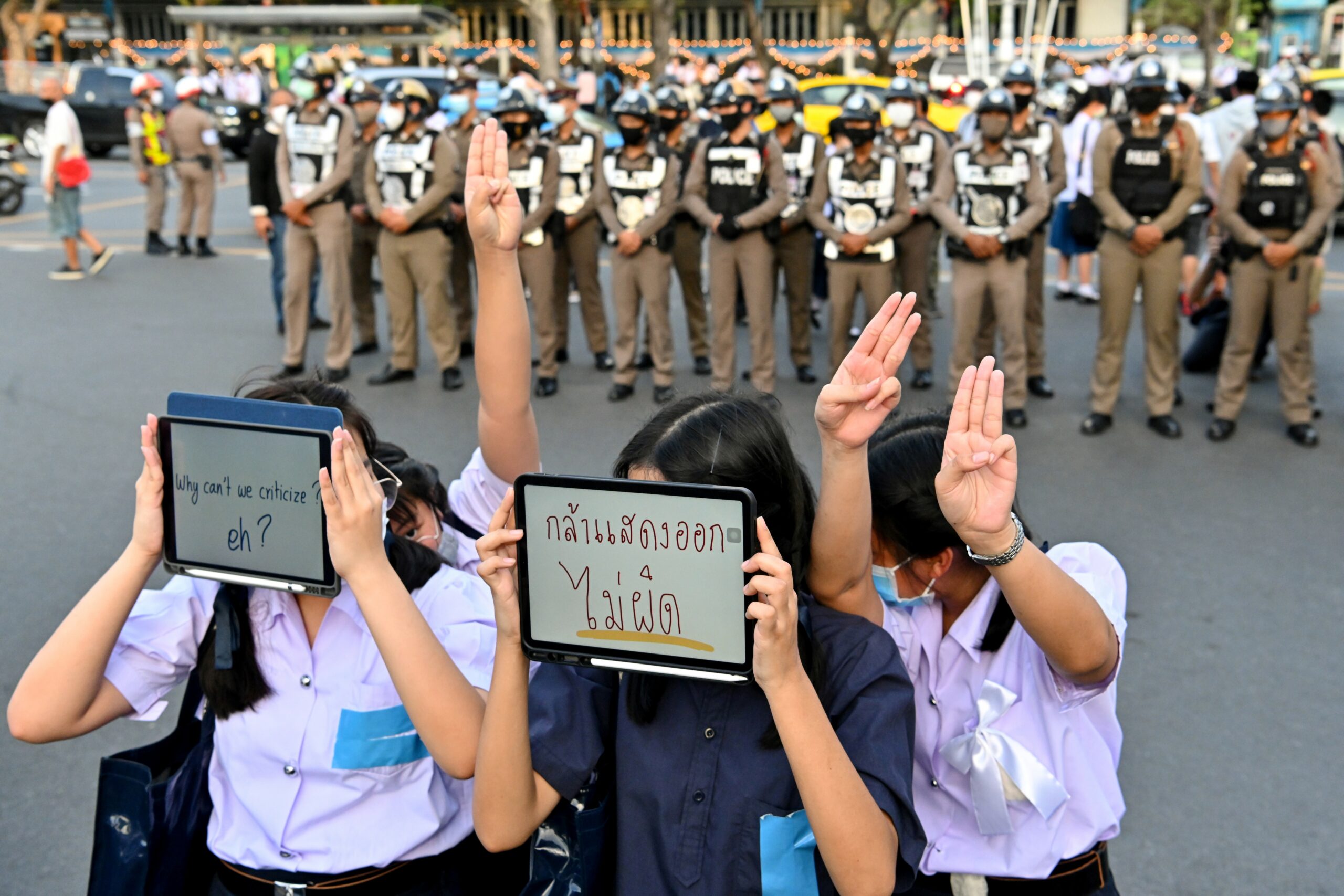

Stories from Thailand show that a wide-ranging crackdown on fundamental freedoms has been carried out by the military-led regime.

“The government’s goal is to truly put an end to the pro-democracy movement by exhausting activists physically and mentally in order to maintain the authoritarian establishment in power,” said Emilie Pradichit, founder and executive director of Manushya Foundation, and co-author of Freedom on the Net: Thailand Country Report. “Now, more than ever, we must mobilise and join forces to resist Thailand’s digital dictatorship and ensure pro-democracy activists remain strong and brave and can care for themselves as a priority.”

In its attempt to create a chilling effect on society as a whole, the government even used Pegasus spyware technologies to monitor, harass and silence activists, human rights defenders, journalists, and others who expose abuse and demand change. These targeted activists are fighting back – in October, they launched the first-ever lawsuit in Southeast Asia against the producer of the spyware, NSO Group.

Clearly, free speech does not come without a price. But others in Thailand have found it more difficult to fight state repression of their digital rights.

Within less than two years, Thai police have charged more than 200 people under the draconian lèse-majesté law that authorities have used to target discussions of the monarchy and institutional reform. Worryingly, many of these people face multiple criminal charges and could receive prison sentences that range from one to three hundred years.

In one of the most draconian and inhuman sentences up to now, a former revenue officer was sentenced to 87 years for uploading on YouTube audio clips of a radio host who criticised the monarchy. Later, the sentence was reduced, but only by half, and that was after she pled guilty.

January 2023 was undoubtedly a month of hardship. In one fell swoop, the human rights situation has taken a drastic turn for the worse. On 26 January, pro-democracy activist Bas was sentenced to 42 years in prison – reduced to 28 for being cooperative – for Facebook posts “defaming” the monarchy. Also in January, the bail for two pro-democracy activists was withdrawn, while Tawan and Bam – withdrew their own bail to call for the release of all political prisoners. “Blood for blood. We demand our friends’ lives back,” said Tawan and Bam. They are currently on hunger and water strike, and their health is greatly deteriorating. How many more people have to suffer before the Thai government starts respecting human rights?

Cracking down on activism

However, this is not an isolated phenomenon in the region, but rather widespread. In Cambodia, activists, human rights defenders, netizens and members of opposition parties are harassed and imprisoned on account of their online activities.

Members of the court-dissolved Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) have been sentenced and prosecuted for political speech. In June 2022, no less than 50 CNRP members and supporters were found guilty for their activism, which included social media posts expressing critical views of the government.

Authorities in Cambodia have even sought to establish a single internet gateway that would facilitate greater censorship and surveillance. The proposal has yet to be realised, but has sparked alarm within the country’s civil society.

Internet freedom is also under threat in Indonesia, and authorities disrupted Internet access in parts of the country, such as Papua and Wadas village in Central Java. But even if authoritarianism expands both in the region and in Indonesia – especially in light of the recently passed new Criminal Code – civil society resistance is also increasing.

On 30 November 2022, Indonesian civil society organisations filed a lawsuit against the Ministry of Communication and Informatics over its decision to block access to a number of online platforms that had violated the law by failing to register with the government.

Slightly better placed in the internet freedom index is Malaysia; yet, in the past few years, many online users and critics of the monarchy, government, or the Islamic religion have been arrested. Authorities censored LGBTIQ+ content, severely impacting these communities, increasing their isolation and inhibiting efforts to publicise rights violations and abuse.

In Singapore, authorities have arrested and sentenced people for their online activities, particularly for speech deemed critical of the government or racially divisive. Daniel De Costa, a contributor to the news website The Online Citizen, the longest-running independent online media platform that covers topics not generally covered by mainstream media, was sentenced to approximately four months in prison over a letter he wrote regarding government corruption.

The digital grip of dictatorships

The Philippines has taken a turn towards authoritarianism over the past years and the return of the Marcos family with the May 2022 election of Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. as president signals a stark reminder of the dictatorial rule under Ferdinand Marcos Sr.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists’ Global Impunity Index, the Philippines is the seventh most dangerous country in the world for journalists. The murders of at least 13 journalists, including two radio commentators, are still unsolved as of 2022. Percival Mabasa, a vocal critic of Duterte and Marcos Jr., and Renato Blanco were killed within the first two months of President Marcos’ administration.

Across the sea in Vietnam is separated by the sea but kept close by authoritarian features they both display – information manipulation and a repressive environment for journalists. Vietnam is growing intensely authoritarian, being one of the last strongholds of one-party communist rule in the region. There are more than 200 activists imprisoned for exercising their fundamental rights, including freedom of expression, and at least another 350 are at risk.

Although not covered by the 2022 Freedom on the Net Report, Laos, another closed autocracy with a dismal human rights record, is likewise governed by a one-party rule that dominates all aspects of politics and restricts civil liberties. Critical speech is criminalised and repressive laws are used to crack down on everyone speaking truth to power. That is the case of prominent human rights defender, Houayheuang Xayabouly, also known as Muay, who is currently facing a prison sentence of five years in addition to a fine, and was arbitrary arrested and detained since September 2019 for denouncing the Lao government’s corruption via Facebook live streams.

Rising up against digital authoritarianism

While it is impossible to depict Southeast Asia in a single picture, it is easy to identify the main direction that the region is heading towards – which is autocratic hardening. We may have moved from Covid-19, but the virus of digital dictatorship keeps spreading. In Thailand, there is a high chance that the situation will get worse this year. The general elections are scheduled for May and the youth will certainly voice their concerns, demand political change, true democracy, and free and fair elections – the 2019 elections were far from being free and fair.

Looking at the situation in Myanmar, Indonesia, Cambodia, the Philippines, considering that Laos is totally closed, that Vietnam has prepared new rules to restrict content on social media platforms, and that Thailand might soon become the country with the most political prisoners in the region, we need to continue to speak with one unified voice and amplify our concerns against rising digital authoritarianism.

This is the very reason why we co-created the ASEAN Regional Coalition to #StopDigitalDictatorship: To spark an online revolution and restore our digital democracies. Together with courageous human rights groups from Southeast Asia, we have tirelessly advocated for the respect of digital rights, named and shamed authoritarian governments to hold them into account, and to tell the world #WhatsHappeningInASEAN.

Digital authoritarianism in Southeast Asia is not just a danger to those who live within its borders. It is also a peril for the rest of the world. That’s why not only regional, but also global solidarity is needed to echo the call for online freedom.

Digital rights are human rights and they must be respected – full stop.

Emilie Palamy Pradichit is the Founder & Executive Director of Manushya Foundation. Letitia Visan is the Human Rights Research & Advocacy Officer of Manushya Foundation, specialised in digital rights and access to justice before the UN. Emilie and Letitia have co-authored the 2022 Freedom of the Net’s Thailand Country Report and coordinate the work of the ASEAN Regional Coalition to #StopDigitalDictatorship.