Filipino photographer Vicente Jaime R. Villafranca — “Veejay”, for short — frames his entire job, quite literally, around looking at things differently.

“The work I’m most interested in delves into a reexamination of how Filipinos, or at least my subjects, have been portrayed in the past,” he says. “A reexamination of the representation of certain individuals and groups of individuals.”

The 37-year-old documentary photographer was born in the early 1980s in Manila, and has sought to do the region justice through his work, which has ranged from quick news hits to in-depth photo series.

Villafranca got his start with an internship at national news magazine Philippines Graphic, with no experience and armed with just his camera. It took him a year and four months, but after a lot of hard work, he became a staffer.

His family, though slightly wary of the unstable income offered by the industry, was nonetheless supportive, with Villafranca’s grandfather a print journalist in the 1970s and his father a photojournalist.

Today, part of Villafranca’s job entails throwing himself into situations that might cause others to hesitate.

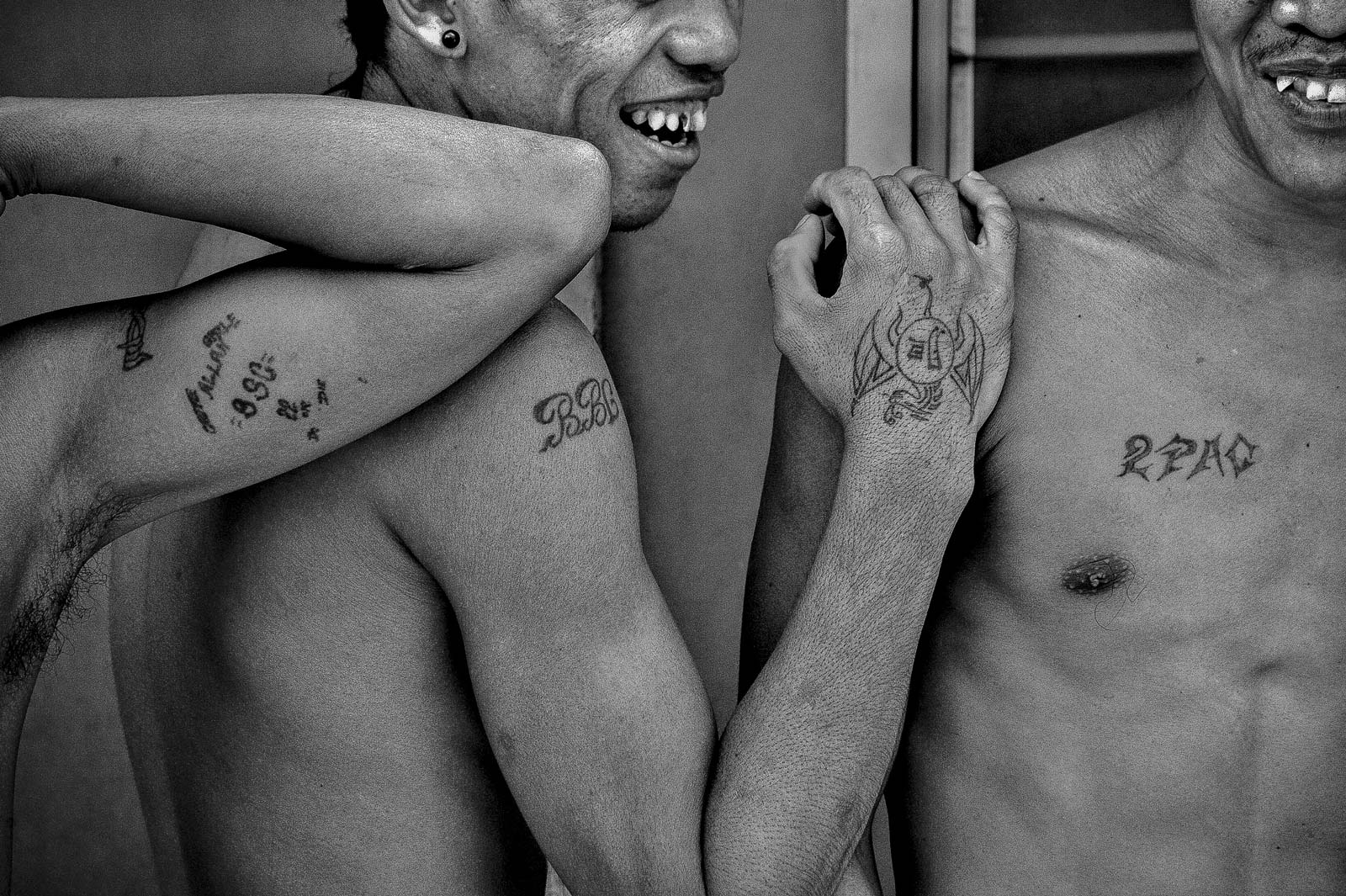

An early project shot between 2006 and 2010 that earned him notoriety served to peel back the curtain on the lives of members of the feared Chinese Mafia Crew operating in the nation’s capital. The gang, who took their name from a local hip-hop group, was based at the Bataan Shipping and Engineering Company (Baseco) compound in Manila’s Port Area before it burned down. As Villafranca writes, “they decided to use the tragedy as an opportunity to rebuild not just their houses, but their lives as well.”

With that project, called “Marked: The Gangs of Baseco”, Villafranca’s reexamining of representations of the gang included sifting through the stereotypes of toxic masculinity that often overshadow gang members, in the process showing “a side of them that was aspirational”.

“I was looking for details in their daily lives that would illustrate a different facet [to their personalities],” Villafranca said. “I think that everyone has that. I think every human being, person, group of people, has different sides to them.”

It took him five months of taking only a few photos and slowly building trust with group, but eventually he honed in on their love of music and dancing, as well as their community spirit.

Climate change

These days Villafranca’s focus has shifted towards climate change – a subject matter that to him, and many others worldwide, is more pressing than ever before.

Almost exactly a decade ago, on September 23 2009, Typhoon Ketsana ripped through Manila and the surrounding region. Known to locals as “Tropical Storm Ondoy”, the typhoon killed 747 people and caused over a billion dollars in damage.

In most coverage of the event, Villafranca kept seeing the word “resilience” pop up. One non-governmental organisation even ran an ad that featured a peppy pop song over scenes of children playing in the rubble of the city. Something about this bothered him.

“People kept saying, ‘Oh, they’re so resilient, even after the typhoon, they’re smiling and they’ll be rising up again soon,’” he said.

From then on, Villafranca decided he would focus on creating fundamentally realistic depictions showing the full impact of climate change, especially as it disproportionately affects low-income countries. He has also covered displacement and human trafficking, issues that climate change can both cause and exacerbate.

This work culminated in the publication of his book in 2017, six years in the making, called Signos (meaning “dark warning”) – a poignant photographic portrayal of the lives of those impacted by severe weather patterns in the Philippines. “Nothing captures the country’s vulnerability to climate change quite like these images,” TIME Magazine wrote of the book upon its release.

Villafranca wants those impacted at the forefront of the images he creates. High contrast, strict black and whites or punchy colours, and only the most strategic blurring draw the eye to exactly what he wants you to see – the humans at their core.

The zeitgeist in the Philippines is also a prevailing component of his work, with a lot of Villafranca’s photography taking the shifting mechanisms of familial relationships, popular culture and socioeconomic issues into account. In one as-yet unreleased project, the production of which is ongoing, he focuses on Filipino spirituality and belief systems.

Meaningful work

Villafranca recognises that these days, finding meaningful work in the field of journalism and photography can be difficult – with this one reason why he’s intent on giving back to aspiring photographers. Early next month, he is set to teach a series of workshops to young Asian photographers as part of the Angkor Photo Festival, an annual event held in Siem Reap, Cambodia for the past 15 years. This year’s event will take place from December 3-7.

The workshops were originally intended to provide photographers from developing Southeast Asian nations the opportunity to learn from industry experts with experience producing work for an international audience. Villafranca himself was a student after the workshop’s conception in 2005, and he sees his current role as instructor as one that includes encouraging participating photographers to look inward and closely examine their own countries.

In an age of sensationalism, fake news and untrustworthy news sources, Villafranca says he hopes to instill one thing in the budding artists present at his workshops as they hone their craft and move into their future careers – responsibility.

“Photography is often intrusion into the lives of your subjects, so this intrusion entails a sense of responsibility … that’s something I hope that the new generation of photographers will keep in mind.”