Every night since the February 1 military coup, Burmese film student Le Yee has been obsessively trawling news outlets and the social media accounts of activists and journalists in Myanmar.

On her own Instagram, she does everything from reposting footage of the military’s escalating violence against anti-coup protesters, reporting on the daily death toll to translating on-the-ground updates in Burmese.

Cut off from her homeland, the 21-year-old does all this from her university dorm room in Singapore close to midnight, in hopes of spreading awareness about the atrocities happening in Myanmar and pressuring large international organisations to act.

Sometimes it gets so bad and she feels totally helpless, Le Yee confesses. When she takes all the news at one go, she feels a wave of emotion like a “tempest”. But she steels herself upon seeing the courage of the Burmese youths – some even younger than her – continuing to fight for democracy, despite knowing that they might get killed on the frontlines.

“These kids have dreams and aspirations like me, but they are ready to give it all up for their country,” Le Yee told the Globe.

For many of the Burmese diaspora across Southeast Asia, the coup has taken a crippling emotional toll. Myanmar nationals living in Bangkok, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea have thronged the streets to protest outside embassies and flash the three-finger salute in a show of resistance.

In Singapore however, the country’s notoriously strict rules on public assembly mean it is illegal to organise or take part in a public assembly without a police permit, limiting the ability of the city-state’s Myanmar diaspora to physically express their solidarity.

Foreigners have also previously been warned against importing other countries’ politics into Singapore, and days after the coup, the Singapore police warned against plans to hold protests in relation to the ongoing political situation in Myanmar. Amid these restrictions, many Burmese in the Lion City continue to rally against the military dictatorship – albeit through the online sphere.

For Le Yee, the military coup is an “intense reminder of her absolute privilege” of having grown up in the safety of Singapore since she was three, and being able to receive quality education.

Though her family doesn’t talk openly about their feelings, Le Yee knows her parents are devastated by the bloody clashes. Lately, her parents have been recounting stories of how they narrowly escaped the violent military lockdown of the University of Yangon during the 8888 Uprising. Their university education came to a halt. They had seen beheadings with their own eyes and dismembered heads hung on street lamps.

Le Yee recalls watching her mother hum a revolutionary song the entire day as she cooked, cleaned and did household chores, all the while her phone on the dining table was tuned in to an endless stream of news.

“It was heartbreaking. Physically she is here in Singapore, but mentally and in spirit, she is with the Burmese people, protesting out in the streets,” she said.

Like most Gen Z youths, 21-year-old Phoo is savvy, hyper-connected and vocal.

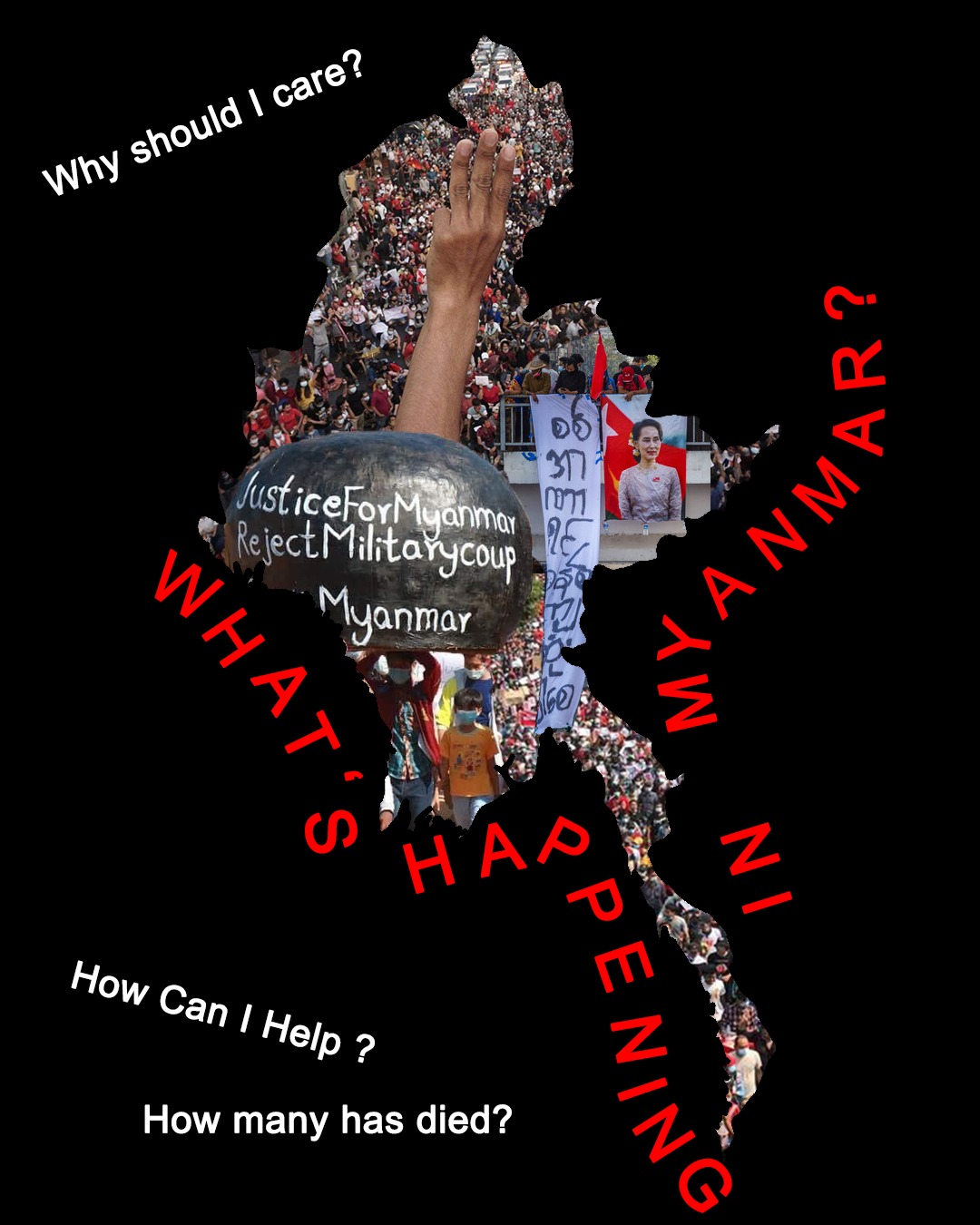

The final-year arts management student is behind the viral @whatshappeninginmyanmar LinkTree page, a consolidated resource list which she created on the first day of the coup.

The page includes links to statements to the UN Security Council, how to support the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), the HK19 Manual with crowdsourced protest tips from the 2019 Hong Kong protests translated from English to Burmese, advice on how to write to members of Parliament in Singapore, as well as links to online platforms championing the voices of the Myanmar people.

As of late March, the page has received over 35.6K clicks, with viewers from the US, Singapore, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Germany and India.

Having joined as a member at the Global Movement for Myanmar Democracy, Phoo finds a newfound sense of solidarity and connection with Burmese youths around the world she has befriended over Instagram.

Phoo has also been feeding updates on the actions taken by Singapore in relation to the coup with rights group Justice for Myanmar. In the early weeks of the coup, Phoo volunteered for Queer Zinefest, which sold zines and prints by Burmese artists from the Yangon-based Myanm/art gallery to raise some S$2,000 ($1,480) to fund Myanmar artists and CDM efforts.

“I feel so much anguish and it’s because of the close connection I feel to Myanmar,” says Phoo, who has lived in Singapore since she was 10.

Despite her efforts, the soft-spoken student insists that she is an “accidental activist”.

These days, Phoo has taken to sending messages like “take care”, “love you” and “I hope to see you another day” to Burmese photographer friends she has befriended online, as crackdowns by authorities grow increasingly violent against protestors in Myanmar.

She frets every time she doesn’t hear back from her relatives in Yangon amid the frequent internet disruptions. Just the other day, she heard how her aunt had run away from bullets, while her cousins spent a night hiding out at a stranger’s home when soldiers sealed off the roads in the Sanchaung Township, northern Yangon.

School work has kept her a little more sane – the alternative would be spending the day “doom scrolling”, she jokes.

Still Phoo is hopeful, seeing how the CDM has expanded from an online campaign to a wider pro-democracy movement, with medical and health care workers, bankers, lawyers, teachers and engineers refusing to return to work. The movement has recently been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for 2022.

“I have faith that through non-violence, the CDM will hit the Tatmadaw where it hurts the most,” Phoo said.

There are some 200,000 Myanmar nationals in Singapore, with many of them taking up laborious and low-wage jobs often shunned by Singaporeans, such as construction workers and domestic helpers.

Singapore businesses have also had a strong business presence in Myanmar in recent years, as political and economic reforms have seen more investors flocking to the once-isolated country.

But as the West looks to apply tougher sanctions against Myanmar’s military, Singapore has been facing mounting scrutiny and calls to sever economic ties. Singapore remains Myanmar’s biggest foreign investor, with US$24.1 billion, as of December 2020, in approved foreign capital – surpassing even China.

While Singapore has carved out a strong reputation as a global business hub, rights groups like Justice for Myanmar and Burma Campaign UK have uncovered a dark side to its business dealings with Myanmar, and named-and-shamed such firms in investigative reports and ‘dirty lists’.

Filing a police report is the most Singaporean thing you could do

Following online pressure by activists just days after the coup, Lim Kaling, Singapore co-founder of gaming company Razer, announced that he would pull out of a joint venture that owns tobacco company RMH Singapore, which owns 49% of Myanmar’s biggest cigarette maker, the military-owned Virginia Tobacco.

While Singapore, along with Indonesia, has been most vocal in ASEAN in condemning the military’s actions, watchdogs and rights groups feel its stance has not been strong enough given its economic clout in the country.

In mid-February, Singapore’s Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan stressed that politics and business should be kept separate. And while Asean states can play a discreet role in helping Myanmar return to stability, he said that the bloc has a longstanding policy of non-interference in domestic politics of member states. In a BBC interview earlier this month, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong also reiterated that “outsiders have very little influence” on Myanmar’s path forward.

In light of government caution, ordinary citizens like Swe Sin Tha, a feisty 24-year-old coding developer in Singapore, are taking matters into their own hands.

In February, she filed a police report against two Singapore companies, Excellence Metal Casting and freight company STE Global Trading, believed to be linked to breaking UN sanctions on North Korea and enabling the Burmese military to procure weapons from the repressive state.

The firm is registered under directors Lim Ching, a Singaporean national, and Tun Hlaing, who is reportedly the head of the Myanmar Directorate for Defence Industries – a part of the Tatmadaw.

“Filing a police report is the most Singaporean thing you could do,” she explained. “I knew that whatever protests that take place, nothing major will happen until the people in power are shaken.”

Six years ago, on the day of the 2015 Myanmar election results, this writer met Thazin Thant and her family at their office at Peninsula Plaza (the Little Myanmar of Singapore). The prominent family ran Singapore’s only, and now-defunct, Burmese magazine. They also organise events and outreach for the community, and provide cash top up and transaction services.

They had been heavily involved with that year’s elections – from setting up a Myanmar election survey group on Facebook, helping the Myanmar Embassy in Singapore with the polling paperwork, to recording a music video to drum up support for Suu Kyi’s NLD.

When they heard the NLD had won their landmark victory, they were in high spirits, thinking it would bring a new era of democracy and development.

But things couldn’t be more different now.

When this writer met the family again one recent Thursday afternoon, she was struck by how forlorn their office space looked. Business was almost non-existent, with economic activities in Myanmar heavily disrupted by the ongoing unrest. Still, the family perked up at the chance to voice out the pain they had been feeling.

Over steaming hot milk tea and lahpet thoke (Burmese tea leaf salad), Thazin’s father Aye Kywe spoke about Myanmar’s tumultuous journey to democracy, from the 8888 Uprising to the 2007 Buddhist monk-led Saffron Revolution. In 1992, he left his hometown Sitkwin for Singapore, convinced that the prospects were better than life under harsh military rule.

For over 20 years, the family carved a life for themselves in the city-state, making the occasional trip back to Myanmar. When whispers swirled in late January about a possible coup, they thought it was impossible. But on February 1, their worst nightmare came true.

It’s a rollercoaster, sometimes you feel so angry, sometimes so sad, sometimes speechless. You never know until you cry for someone you’ve never met before

Thazin’s mother, Theresa Khin, has been so distraught that her home is in disarray. She has no mood to clean, cook, meditate and only turns up at the office twice a week. Instead, the 56-year-old prefers to spend all her time on the web.

Since the coup, she joined a 200k-member strong Facebook group “The Keyboard Players (Keyboard Fighters)”, where they keep tabs on the ground, compile photos and videos as evidence of military brutality to flagging fake news and misinformation.

Theresa also created her first Twitter account to post messages of encouragement and criticism of the junta’s actions, which she described as “war crimes”, while she also sends regular updates to Dr Sasa – the envoy representing Myanmar’s Parliament to the UN, the CRPH, who has since fled Myanmar – providing video footage of shootings or beatings perpetrated by the Myanmar military.

Thazin is following in her mother’s footsteps as well. She helps to translate news and letters, and has raised some S$1500 ($1,100) through personal contacts to supply shields and gas masks for impoverished townships through the CDM.

In early March, a close friend of theirs had been running away from the soldiers, fearing detainment, when his vision was affected by tear gas. He hit a pole and died. The death of protestor Angel, who died after being shot in the head in Mandalay earlier this month, also hit particularly close to home for Thazin.

The teenager, whose real name was Ma Kyal Sin, reminded her of her cousins in Myanmar, she told the Globe.

“It’s a rollercoaster, sometimes you feel so angry, sometimes so sad, sometimes speechless. You never know until you cry for someone you’ve never met before,” said 30-year-old Thazin. “Sometimes it’s hoping what little that you do can make a difference.”

Despite the physical distance removing Singapore’s Burmese diaspora from their homeland, the gravity of the fight – just how much is at stake – is not lost on them.

“Myanmar people do or die. It is now or never. We must win this time, not let the military bully the people,” Theresa said. “If not we will never see change in our lifetime.”