The biennial Singapore Writers’ Festival is one of the few multilingual literary festivals in the world, celebrating written and spoken word in Singapore’s official languages – English, Malay, Tamil and Chinese. Despite being a young nation, the cultural and literary scene of the city-state is blooming, with a myriad of diverse voices rising up to share their narratives.

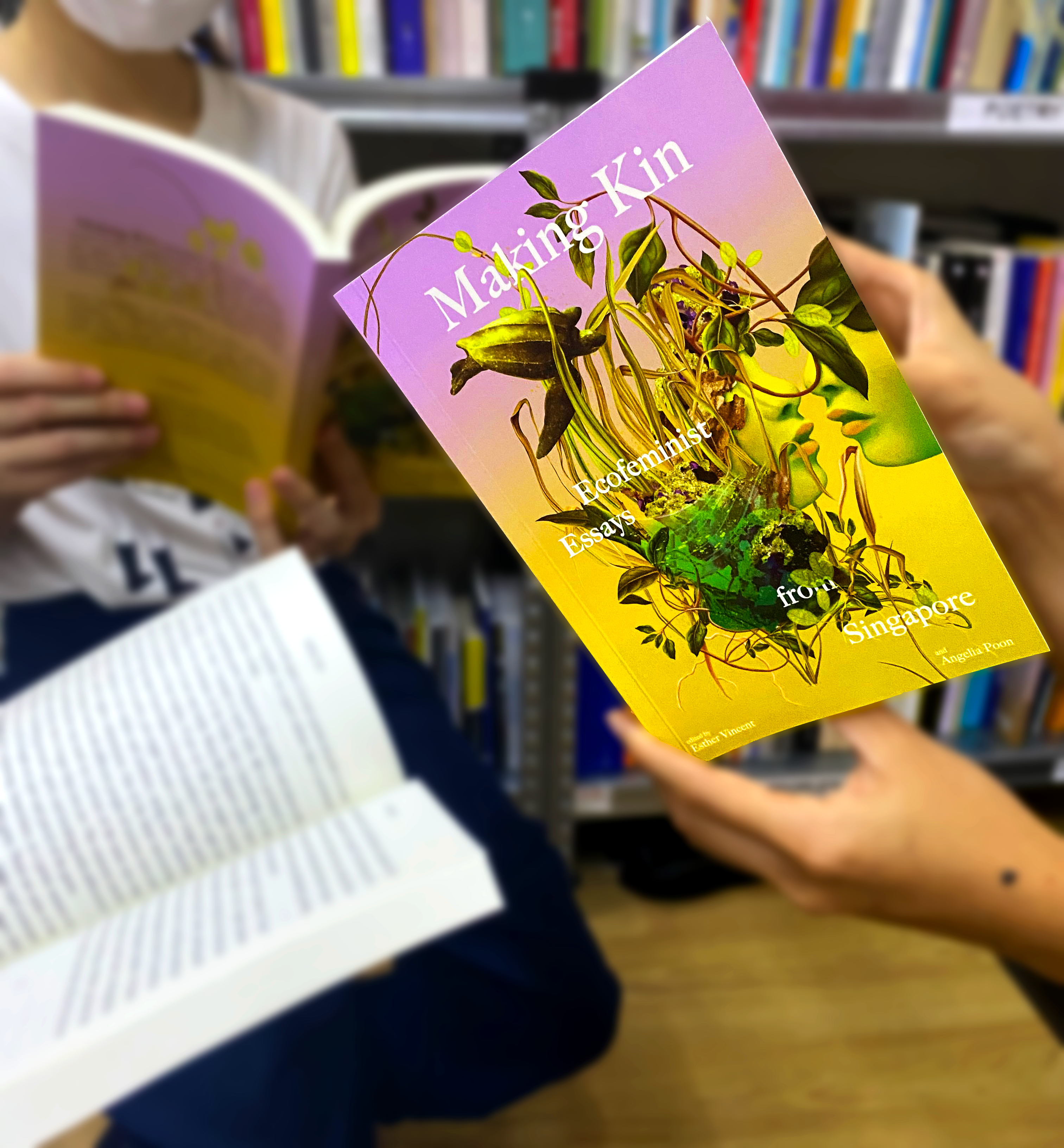

As the festival approaches on 5 November, Globe spoke to Esther Vincent, co-editor of Making Kin, a newly published anthology of ecofeminist personal essays from Singapore, written by women of various backgrounds.

From ruminating on the significance of home and physical spaces, to acknowledging the power of naming wildlife, Making Kin is a reflection and response to how women navigate their experiences across the intersectionality of gender, politics and other critical environmental issues, and how they find their place within it all.

How did you settle on the subject of eco-feminism for the essay compilation? What does the term ‘ecofeminism’ mean to you, and why is it so significant today?

For my graduate studies, one of the chapters of my critical exegesis was on ecofeminism. I examined the relationships between woman and nature in the poetry of Eavan Boland and Grace Nichols. I wanted to foreground the importance of women in Singapore engaging with environmental themes in the personal sphere, showing how these enactments were political, and how they matter more than ever today. I fielded this project to my co-editors from [previous work] Poetry Moves, and Angelia Poon was keen to co-edit with me. And so Making Kin was conceived.

To me, ecofeminism is a way of looking at the entanglements between women and the earth. Ecofeminism is interested in the voices of women and their lived experiences and how they form kinships and entanglements with others within environmental discourse.

I think this is significant today because of the way humanity has ravaged and damaged our earth on a mass scale. We need to find ways to heal these broken relationships with our earth. We need to find ways to remember that we are a part of a wider web of ecology, that we live and breathe only because others live and breathe with us. Making Kin hopes to offer kin-making in times of ecological crises and division.

The title Making Kin has connotations and connections to family and kinship. What is the role family plays in this anthology?

Central to the idea of family is the theme of home and belonging.

Family to a child can include the tiger moths and weeds that she plays with, just as home might mean an empty field. Family can allude to ties that continue in spirit even after the physical death of a loved one. Family can encompass an entire fishing community to a researcher who chooses to marry into the village, or can mean forming kinships with other families across the seas to create communities of care that transcend geographical borders.

Family is central to this anthology and Making Kin asks: Who is my family? Where am I home? What kinships have I forged, can I forge, am I forging, to allow myself to belong at home on earth?

What made you choose the personal essay format for Making Kin?

This also relates to my personal journey as a writer. I primarily write poetry, but during my graduate studies, I started reading more personal essays during my creative writing seminars and as part of my own research, and then writing them.

I enjoyed reading personal essays, which I found intensely intimate yet profoundly salient pertaining to larger thematic issues. I liked how the essay offered the writer and reader a terrain to journey in and the room to manoeuvre and meander. I liked how the female voice could speak freely in this form, drawing from her private and personal life to make a political commentary without coming off as too informal or too political. Angelia and I also wanted to foreground the personal essay, which never seemed to take off in Singapore literature, unlike how local poetry has flourished.

How did you go about the selection process for the essays? What overriding theme did you want to continue through the work? Is there a common shared characteristic between these diverse authors?

My co-editor Angelia Poon and I had a rough idea of certain voices we wanted to represent and we worked closely with our publisher Ethos Books to refine the shortlist before we approached the contributors. We’re very happy with the final selection of 18 contributors (editors included) whose profiles exemplify the kin-making ethos of transcending borders. We wanted to include voices from outside the ‘Sing Lit’ canon and so we have artists like nor and Dawn-joy Leong, activists like Constance Singam and Tim Min Jie, and we also have some more recognisable voices from the Singapore literary scene like Grace Chia and Tania De Rozario.

Our definition of ecofeminism is broad and inclusive and we made an effort to hold space for a range of kin-making stories. We sent contributors an open call brief which outlined the themes of the book and worked with contributors to shape their essays according to their strengths in the fields they represented.

The essays in Making Kin contemplate themes of kinship, entanglements and empathy by drawing from Donna Haraway’s essay “Making Kin: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene”, where she deconstructs the notion of kinship. Referring to Shakespeare, who puns on kin and kind, Haraway proposes a renewed definition and understanding of kin: kin-making as person-making, not limited to human beings alone.

These women are said to be “chart[ing] a new path on the map of Singapore’s literary scene”. Do you think that there is enough representation of women across Singapore’s literary landscape? What can be done to achieve greater representation?

Angelia and I, and our publisher, were mindful of not merely including voices from the literary scene and so we have a range of contributors who might not be known conventionally as writers of Singapore literature. I think this act is quite powerful and embodies what it means to make kin in the making of our book: to have women from various, seemingly unrelated backgrounds and contexts. In this way, Making Kin is a pioneer in Singapore literature.

What can be done is for women to write and for women editors to edit more work by women writers as an act of solidarity. Publishers also have to support the work of women in the industry and more readers should want to read the work of women. It’s an entire ecosystem but it begins with the reader and writer. The onus is [also] on the reader to demand greater diversity and representation, and where gaps exist, they can then come up with ways to fill those gaps, which is kind of how Making Kin came into being.

This collection is said to blur boundaries between the personal and the political. How has your own experience of the political and personal shaped your writing and what major political events have shaped these essays?

The personal is political, a famous feminist slogan, asserts that policies on paper trickle down into the lived experiences or the private lives of individuals. In my essay “The Field” for instance, which was first published in Sinking City, I write about my dreams, a largely personal and private space. Seamus Heaney and Eavan Boland refer to this idea of the symbolic “country of the mind”. I think Singapore especially, with its constantly changing landscape, qualifies as a “country of the mind”, a remembered and reimagined place (which differs for each individual who remembers and reimagines their version of Singapore), and I grapple with these notions of memory, place, home and belonging, amongst other themes, in my essay.

The other essays in the collection similarly centre the personal lives of the women contributors to comment on larger political concerns, as reading them will reveal. Former journalist and literature academic Matilda Gabrielpillai for example reflects in “As Big as a House” on the meaning of home and the physical environment in her life. She ruminates on the symbolic significance of a house in many works of literature, and her narrator recounts the various places she has lived in growing up, showing how these homes reflect the changing face of the nation.

As varied as they are, there is no one key political event that has shaped the essays, though a recurring theme is the land use policies in Singapore, as well as land redevelopment policies that have altered our relationships to the land.

The start of the book (“Land Acknowledgements”) writes about Southeast Asia’s healing from the scars of colonisation – how does writing (and perhaps the arts in general) help us to realise that?

Writing is an active process; it gives the writer, characters, narrators and speakers of a text agency and voice. It gives voice to our subjects too, which may or may not be human. Writing, as an act of imagination and recovery, can be a powerful tool of reclamation, of taking back what has been taken from us and giving life to beings (animals, plants, people, habitats) that have been killed, to stories that have been silenced, to land that has been cleared, to seas that have been reclaimed.

Writing is empowerment. The act of putting thought into words and words onto paper transforms an idea, something abstract into an embodied thing. That to me, the articulation of trauma in writing, can be the first step to healing.

Making Kin is available for purchase from Ethos Books.

Esther Vincent Xueming is the editor-in-chief and founder of The Tiger Moth Review, an eco journal of art and literature, and author of Red Earth, an ecofeminist collection of poetry (Blue Cactus Press, 2021). She is also co-editor of two poetry anthologies, Poetry Moves (Ethos Books, 2020) and Little Things (Ethos Books, 2013). Follow her on Twitter @EstherVincentXM