Singapore is a city state that prides itself for its multitudes of successes; its economy, education system – and even the ageing process.

The country’s proportion of elderly (persons above the age of 65) is projected to rise to 23% over the next decade, poised to make Singapore one of the most rapidly ageing countries in Asia. Greater longevity doesn’t always track directly to better quality of life however, and social researchers are increasingly concerned about the prospects of older Singaporeans to go through “successful ageing”.

That’s a state of living characterised by preventing both social isolation and frailty to the point of dependence. By 2030, as many as 83,000 elderly people could be living alone in Singapore by 2030, a projection that has already prompted local media discussions on dire topics like “elderly orphans” and “how not to die alone”.

But if the crisis facing Singapore’s elderly residents seems far off, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought it into stark view.

While younger Singaporeans can escape into the internet to bypass stay at home orders, their older counterparts are having a far more difficult time leaping the tech hurdles to keep themselves socially connected. Even though social distancing might be keeping people apart, community organisations are now stepping up to look out for their older neighbours in new, sometimes innovative ways.

Ng, a local government official who asked to withhold his full name, described the city’s preexisting support for elderly residents as a web of connections between individuals, communities and state agencies.

“The web is there to catch those at risk if they fall, and like an actual spider web, when something lands on it, the web strands will vibrate along the entire structure,” he said. Ideally, that means elderly residents can get help whenever they need it.

Pandemic or not, neighbours and local communities are a key piece of this network. Ng said the informal connections that wind through the city can both help seniors personally and, through reports made to government offices, link them to aid from the state.

Without that robust community element – and especially during the mandated social distancing response to the Covid-19 outbreak – Ng said the web of public service may become looser, less aware of seniors who need proactive support.

“That makes the gaps larger, heightening the chances of more people falling through these cracks,” he explained.

Singapore has long held a reputation as an individualistic society where traditional communitarian values of the 1960s meet in a sometimes awkward embrace of a fast-paced pursuit of modernity and economic growth.

Singapore’s Department of Statistics provides evidence of a growing trend toward single-person households. Today, about 15% of the city’s households, roughly 208,000 in total, are composed of just one person. That’s an almost two-fold increase from the 8.2% recorded in 2000, and it’s a trend that has made it particularly important for community groups to fill a potential void in people’s lives.

Even before pandemic conditions set in, some studies suggested the workaday lifestyle common to Singapore was setting a stage for elderly isolation.

“We always think that the elderly living alone are the most lonely, and consequently depressed”, said Angelique Chan, ageing expert and executive director of the Centre for Ageing Research and Education in Duke-NUS Medical School. “What we actually found in our research is that they can be living with their family and with their children and still be lonely.”

Intergenerational households aren’t spared from this, Chan explained.

“A lot of the time the lifestyles in Singapore for busy working adults mean you’re out most of the day”, she added. “The grandfather or grandmother is at home, either by themselves or with a helper.”

Before the onset of Covid-19, community organising in Singapore often included helping out at senior citizen activity centres, making meal deliveries, regular visitations and door-to-door outreach.

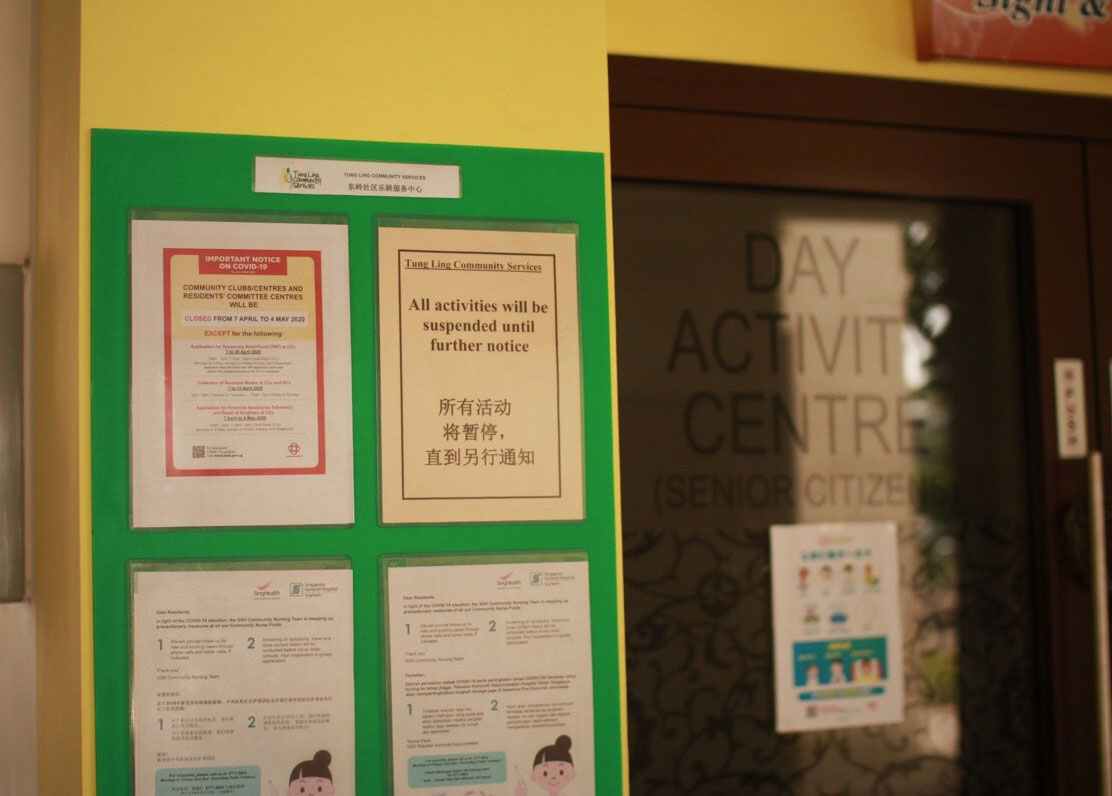

However, all of these things have been compromised in the city’s lockdown. Activity centres are suspended until further notice; door-to-door outreaches and deliveries severely curtailed; family visitations are usually a no-go for the at-risk elderly, and even communal areas such as void decks, eateries and exercise parks have been taped up and cordoned off from their communities.

The reach of the helping hands will not be as extensive as they were before lockdown – and this only applies to the elderly already on the radar of case workers and logged into a database. There are often many who pass under the radar until a neighbour, a social worker or a hospital check-up flags them.

In a March interview, Jeremy Lim, co-director of global health at NUS’ Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, cautioned “we will all pay the price” if Singapore failed to look after its most vulnerable. It was a lesson painfully gleaned from the spike in virus clusters among migrant worker dormitories, which saw Singapore’s Covid-19 response plummet from ‘Gold Standard’ to ‘Cautionary Tale’.

So while the issue of social isolation for the elderly in Singapore has increased since the circuit breaker measures were introduced in early April, several organisations have introduced and adapted existing projects to fit the times.

Most of the existing resources from social service organisations such as the Singapore Red Cross have been channelled into ‘Telebefriending’, a tech-assisted way to connect isolated persons to trained callers who provide support and advice. Other channels are delivering programmes and activities geared at engaging the elderly online, such as cooking, exercise and even a virtual colouring contest.

While more of these efforts have been shifted online, they’re still not the silver bullet to fight isolation in the time of Covid-19. Elderly Singaporeans often have limited access to phones or the internet. Some even have expired prepaid cards, throwing another spanner at attempts at distance telebefriending.

There’s a lot of activity that can go on. Ageing does not have to be a terrible thing in Singapore

Angelique Chan

Tim, who requested his real name be withheld, is a case worker at a social service agency who has taken on additional service as a voluntary safe distancing ambassador. That’s a new vocation in which ambassadors are dispatched to neighbourhood heartlands such as void decks to ensure people maintain a safe distance.

For those involved in roles like his, he said, a little extra effort can go a long way.

“In one instance, they engaged an elderly who shared that she was receiving irregular meal support,” he says. “In their circulation duties and rounds, they could pay more proactive notice to those in need and refer them to relevant sources or hotlines of assistance.”

Those community ties and extra care are vital during the spread of Covid-19. But if the city-state wants to fight the longer health crisis, the endemic spread of elderly isolation, they’ll need to be kept up long after the virus goes into remission.

“Ageing does not actually have to be this dreary process”, Chan said. “You can be generative – we have occasions like retired lawyers teaching younger lawyers. In fact, retired doctors are now coming back to help with the Covid situation. There’s a lot of activity that can go on. Ageing does not have to be a terrible thing in Singapore.”

Ng’s comments are based on personal accounts and experiences working with the elderly, and are by no means representative of local government.