On September 11, in a lake in Cambodia’s Koh Kong province, 15 hatchlings of the critically endangered Siamese crocodile were discovered by conservationist group the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS).

The 15 hatchlings were spotted by one of WCS patrol teams swimming in a lake in the Sre Ambel district – part of a wetland that serves as an important refuge for Siamese crocodiles. “It’s very exciting,” Som Sitha, project manager for WCS Cambodia, told the Globe. “But sadly, I wasn’t there with my team to see it!”

Sightings of Siamese crocodiles are rare, spotting a group of hatchlings even more so. But the recent sighting of the 15 last month comes off the back of 10 hatchings found in the Steung Knoung River in January and another 7 hatchlings found at two different sites in the Cardamom Mountains in August by Fauna & Flora International (FFI). It seems that the outlook for the endangered crocodile may not be as bleak as once feared.

But those who have been working to save the crocodile – with programmes ranging from recruiting former hunters to protect the species they once tracked, as well as the first genetics laboratory for conservation in the Kingdom – are not resting on their laurels.

Cambodia is home to virtually all the remaining Siamese crocodiles in the wild, with experts putting the numbers at around 350 – although, there have been reported sightings in Laos, Vietnam and Thailand.

20 years ago, however, they were thought to be extinct.

Pablo Sinovas, the flagship species manager at FFI Cambodia, explained how when once visiting the University of Cambridge’s Museum of Zoology, he spotted a preserved specimen of the species with the words – “now thought to be extinct in the wild” – on its original label. But in 2000, after some local sightings of the crocodiles, an expedition led by FFI set out to find them.

We recruited former crocodile hunters and put them into our conservation programme … It has been successful turning them from a hunter, to a conservationist

“That expedition in the Cardamom Mountains discovered that there were some remaining individuals in remote parts of the mountains,” said Sinovas.

The freshwater species, a small-medium sized crocodile with a prominent bony crest at the back of its head, had been forced into near extinction thanks to a combination of factors. Historically, hunters poaching the species for their leathery skin was significant.

“One of the major factors was overharvesting,” said Sinovas. “Crocodiles’ skins were quite valuable, so they were hunted for their leather, to near extinction.”

As part of their own protection and patrol programme, WCS now employs a small number of those same hunters – utilising their skills and experience to protect the same crocodiles they once hunted.

“We recruited former crocodile hunters and put them into our conservation programme,” explained Sitha. The former hunters’ knowhow has been an asset in what is challenging work. During the nesting seasons, they go on patrols – on the lookout for eggs, nests and signs of ‘croc-life’.

“It has been successful turning them from a hunter, to a conservationist,” he said.

But hunting – long the scourge of wildlife across the world, not just the Siamese crocodile – is today far less of a problem than it once was.

“It’s not a major threat nowadays,” said Sinovas. “There are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of crocodile farms in Cambodia, where crocs are bred. It makes very little economic sense [to poach] now.”

Instead, the threat centres around fishing practices and the destruction of habitats. Forest clearance for agriculture and communities is an ongoing threat to the species, while fishing nets can cause the crocodiles to become entangled and drown.

In 2016, there were no genetic facilities in Cambodia at the time for conservation work … So we decided to set one up and try to do as much as we could

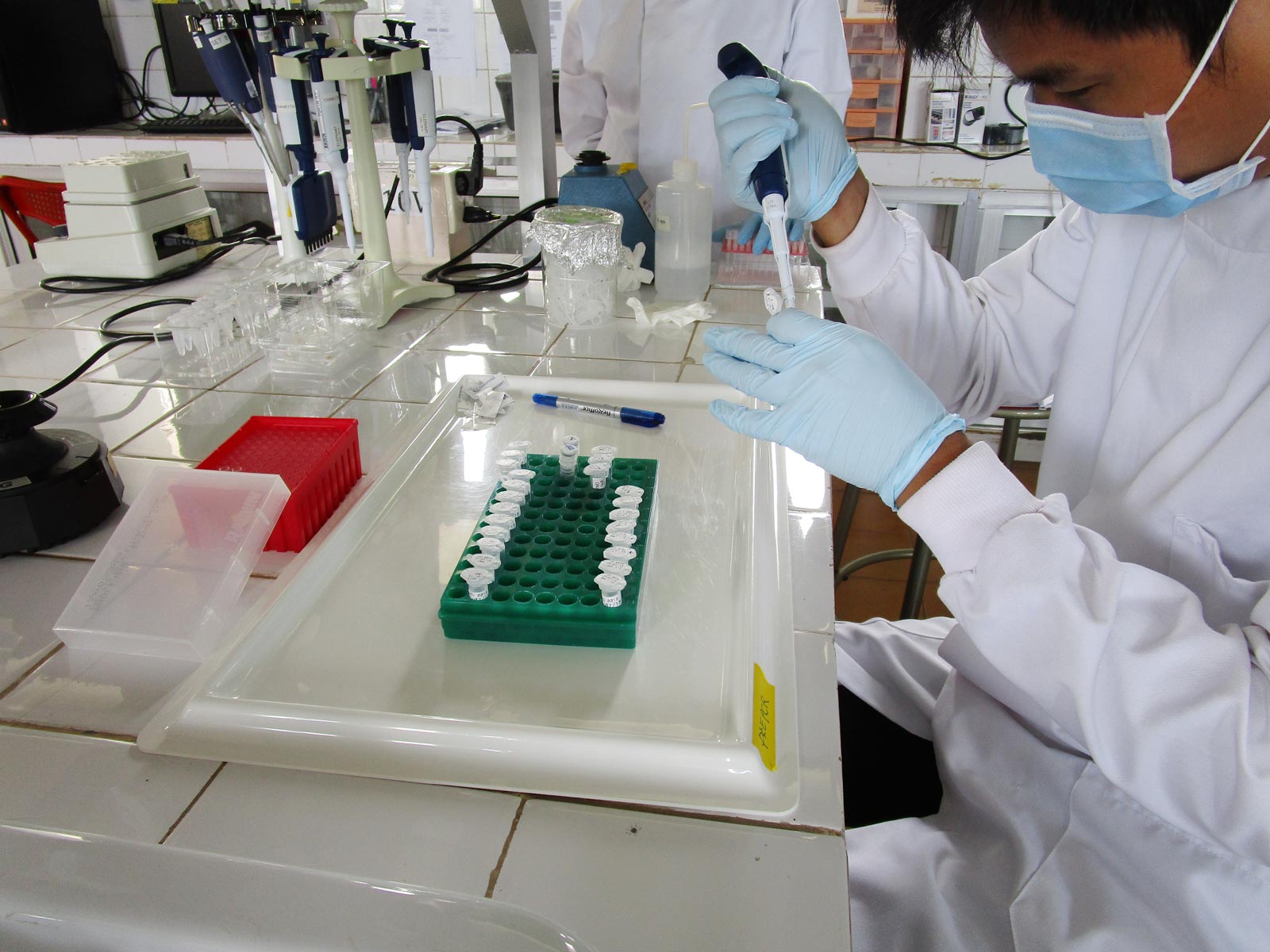

Today, conservation efforts are moving beyond the waterways of Cambodia and into science labs.

“Even within the conservation field, people don’t often fully know about the uses of genetics and how it can help,” Dr Alex Ball, the wildgenes programme manager at the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS), told the Globe. “It’s really about trying to bridge that gap between the questions that maybe we can’t answer.”

The RZSS has been working with FFI and the Royal University of Phnom Penh to develop the first conservation genetics laboratory in Cambodia. “In 2016, there were no genetic facilities in Cambodia at the time for conservation work,” explained Ball. “So we decided to set one up and try to do as much as we could there.”

The new genetics testing methods play an important part in assessing if it is Siamese crocodiles in a given area, from tests on ‘scat’ (or faeces). But one area is of specific focus – identifying which ‘pure-blood’ Siamese crocodiles are to be allowed into FFI’s conservation centres, to later release into the wild.

“Our testing can figure out what proportion of hybridisation has occurred in the history of that crocodile,” explained Ball. “We can sort out whether it’s grandparents were salt water or Siamese crocodiles – and then they can decide what they want to do with that crocodile.”

As interbreeding between Siamese and saltwater crocodiles became prevalent in farms across Cambodia rearing the animals for leather, FFI’s conservation breeding facility, run in collaboration with the Forestry Administration at Phnom Tamao Wildlife Rescue Centre, was designed to help preserve purebred Siamese crocs and help them grow in numbers.

“You of course want to preserve the genetic makeup of the species,” said Sinovas, adding that crocodiles spend two years inside FFI’s facility before being released into the wild.

“What is key to the project is captive breeding,” explained Sinovas. “Because there are so few in the wild, it is unlikely they could recover without help. There’s not enough breeding for the current numbers to one day become a viable population.”

Alongside the breeding work, FFI runs a local project – integrated conservation and livelihoods – which tries to incorporate communities nearby the crocodiles’ habitat into their work.

“We work with the local communities that live closest to these important habitats – they are the ones who patrol the crocodile sanctuaries,” said Sinovas. “On a weekly basis, they go out there – whether in a kayak or on foot – and make sure that any threats, such as nets, are not present.”

But those trying to protect the Siamese crocodile are in no doubt about the work that still has to be done. “I think it’s a hopeful outlook, but I don’t think by any means we’re there yet – we can’t be complacent at all,” said Sinovas. “They are still not reproducing greatly in the wild and you’ve got growing threats in the country.”

But 20 years on from assumed extinction, the Siamese crocodile – albeit in small numbers – is roaming Cambodia’s wildlife once again.

“The slow but ongoing recovery that we are achieving with the Siamese crocodile in Cambodia is one of the few conservation success stories in the country,” said Sinovas. “So it’s encouraging, but we’re not there yet – by any means.”