Wild times have a way of slowing down the clock.

That’s how it can feel, anyway, as the rush of information and news related to the Covid-19 pandemic sweeps the world into an ever-uncertain future. A search for “longest year” on Twitter pulls up hundreds of tweets naming the month of March to be just that.

Users now post everything from status updates marvelling at the far-away feel of recent major events, most of which happened only weeks ago but now feel buried in the sands of time, to memes purporting to show before-and-after pictures of this endlessly intense moment in history we are living through.

For Adrian Bejan, a professor at Duke University in the US and the author of book The Physics of Life: The Evolution of Everything, it all stands as evidence that the march of time isn’t as standard as we might think.

“Human perception is not a continuous thing that flows like wine into a cup,” Bejan told the Globe this week. Rather, he says, “it is a series of clicks”.

It takes a little background information to explain exactly what that means by this abstract concept.

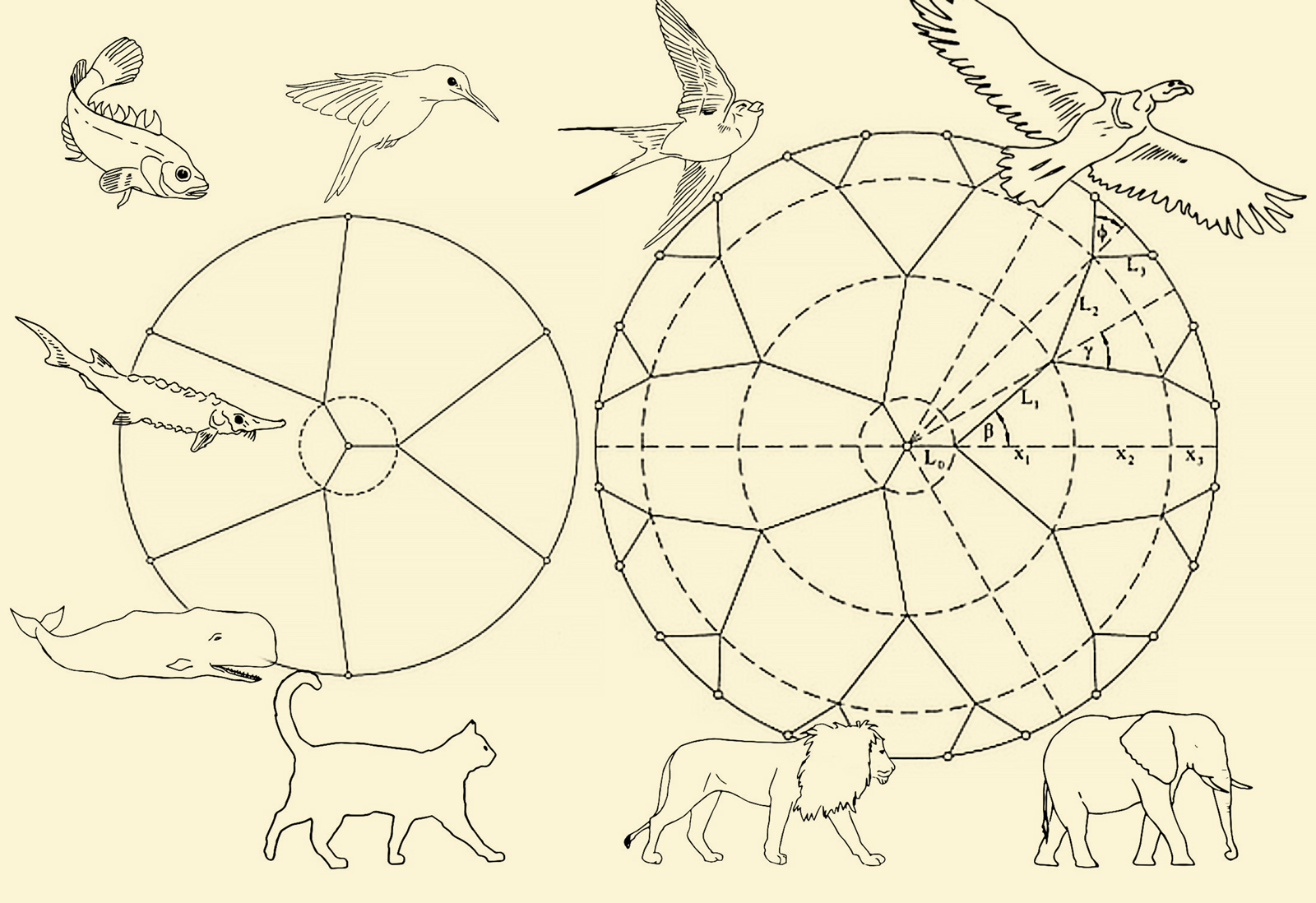

Bejan is a professor of mechanical engineering who’s made a career in thermodynamics, the study of heat and power. That line of inquiry led him to develop what he calls the constructal law of design and evolution in nature. This principle describes the viability of any system as dependent on its freedom to change in a way that “provides easier access to the [outside] currents that flow through it”.

In short: Life depends on being able to go with the flow.

In a period of crisis filled with highly unusual events – much like a pandemic situation – the brain is suddenly confronted with many things that catch its attention. The routine of life is broken and, like the infant, most are now viewing the world as if for the first time

He’s since expanded that theory beyond conventional thermodynamics to the broader questions of life, offering the constructal law as a lens to view evolution, biology and natural history. That’s drawn such comparisons as that between the similar shapes of the branching flow of nutrients through a tree, to the gradual transformation of a river delta.

In his most recent book, titled Freedom and Evolution: Hierarchy in Nature, Society and Science, Bejan writes on perceptions of time accelerating as people get older. While this is the flip-side of the current perception of time slowing down, Bejan says the basic underlying principles are the same.

“If we focus on vision, which is the main avenue of information to the brain, these clicks are like the clicks of an old camera,” he said. “The eyes are jiggling very fast, very briefly in milliseconds, and they scan the image and the image is transmitted.”

During each day, a number of these pictures are transmitted to the brain, which then has the job of picking and choosing which ones to hang onto and build into its view of the world. Bejan likens it to a game of Tetris, with little bricks falling into place to make a growing wall of perception.

“The better the player, the smarter the receiver, the more solid that wall gets,” he says with a laugh.

As we get older, Bejan continues, our ability to build up the wall is affected in certain ways. Not only does the flow of information into the brain get slower due to physiological changes, but the wall of perception has fewer gaps in which to drop bricks of new experience that our brains deem worthy of hanging onto.

He contrasts the sieve of adult perception with that of a baby.

“The eyes of an infant are jiggling all the time, all over the place,” Bejan said. “The infant says nothing, speechless, but this infant is scanning and everything that he or she sees is of course brand new, interesting, worth remembering and worth organising like those bricks in the Tetris game. As you get older and older, you don’t have that.”

Establishing a life of routine can, for the most part, reduce the chances of stumbling across new bits of experience that force their way into the wall. With fewer “clicks” to inform our perception, Bejan concurs, a day can pass with little notice.

“The feeling is that sunset arrived too soon,” he said.

However, he added, in a period of crisis filled with highly unusual events – much like a pandemic situation – the brain is suddenly confronted with many things that catch its attention. The routine of life is broken and, like the infant, most are now viewing the world as if for the first time.

Unfortunately, as many of the March memes have to show, this view is one characterised by stress and fear. But by presenting a daily roster of events that lodge themselves firmly into our perception, the pandemic has effectively made it impossible for many of us to skip forward through time without acutely feeling its passage.

It may be an existential dilemma to be so aware, but it’s one in which Bejan found some silver lining.

“Coming to the present period, it’s horrible, any way you look at it, except that it has the advantage that you’ll never forget it,” he said. “This is an opportunity that comes with tragedy.”

Adrian Bejan is a Romanian-American professor who is J. A. Jones Distinguished Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Duke University in the US. He is also the author of two books, The Physics of Life: The Evolution of Everything, and most recently Freedom and Evolution: Hierarchy in Nature, Society and Science.