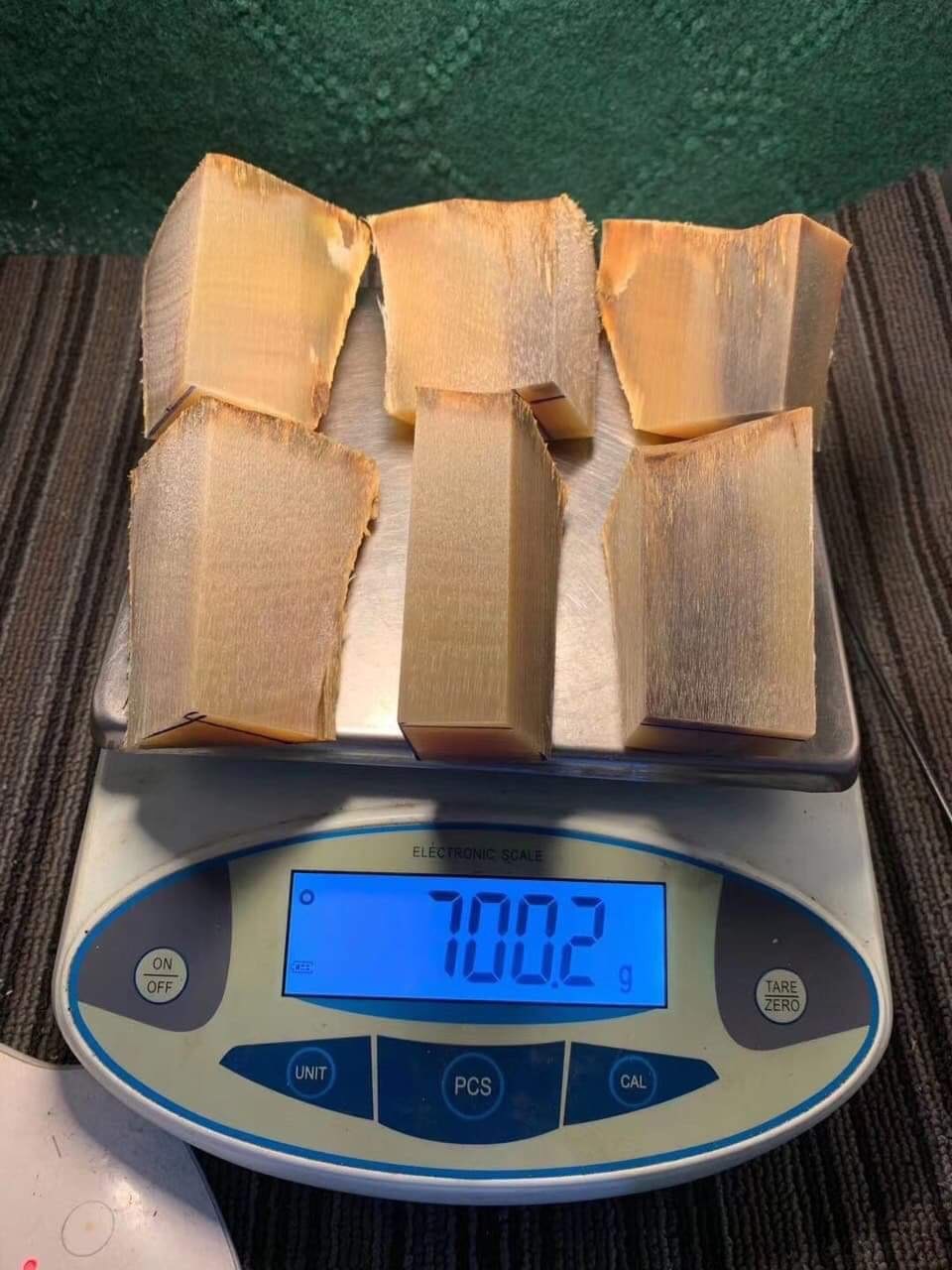

A suspicious package listed as textiles arrived at Hanoi’s Noi Bai International Airport in July 2019. For fabric, the parcel was heavy, weighing in at 126.5 kilograms (278.8 pounds). Customs officials flagged the goods. On inspection, police found 55 rhino horns encased in plaster.

An investigation led police to Do Minh Toan, who was responsible for providing the electronic signature for the contraband. In early December last month, Toan was sentenced by a Hanoi court to 14 years imprisonment for his involvement in trafficking the horns – the toughest punishment to date for a wildlife crime in Vietnam.

Vietnam is the second-largest consumer of rhino horn worldwide, has a major domestic market for wild animal products and is a hub of the international wildlife trade.

The country has made significant progress in the last decade. Toan’s strict sentencing showcases the culmination of efforts to treat wildlife crime seriously in the country. The verdict would not have been possible without an update to Vietnam’s penal code, which went into effect in 2017.

The revision increased the maximum penalty for wildlife crimes from seven to 15 years, added common and less-endangered animals to the list of protected species and for the first time included possession as an offense.

“There’s no perfect law but for us the penal code has played a very important role,'” said Bui Thi Ha, vice director and head of the policy and legislation department at Education for Nature Vietnam (ENV), a Hanoi-based nonprofit combating the illegal wildlife trade in Vietnam. “It made wildlife crime very serious in Vietnam.”

Paradoxically, Toan’s case also highlights the existing weaknesses in Vietnam’s fight against wildlife crimes. While the verdict sets an important precedent, he is a small player in a larger trafficking network. No further arrests have been made in the case, which is unsurprising as large seizures of illegal wildlife products rarely lead to the arrest of trafficking kingpins and facing the problem of rhino horn trafficking head-on poses challenges in an environment where wealthy and powerful members of society are users of rhino horn.

The biggest traffickers have strong connections with customs officials and police, according to Dang Vu Hoai Nam, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Copenhagen studying the rhino horn trade. Nam’s 2020 survey of 1,000 Vietnamese rhino horn users found that 20% to 30% of consumers of the illegal product are government employees.

“I believe if the government really wanted to dismantle the illegal trade of rhino horn they could do it but it is simply because of a lack of resources and because it is not their priority,” Nam said. “A number of respondents in our research are working for the government, so you see there may be few reasons for them to stop the rhino horn trade completely.”

Vietnam’s last rhino was killed in 2010. The female Javan rhinoceros was found shot with her horn removed in Cat Tien National Park – a lowland tropical forest about a four-hour drive from the country’s economic centre, Ho Chi Minh City. Today, all five species of rhinos across Asia and Africa are endangered with fewer than 30,000 individuals living in the wild.

Nam has attended parties where rhino horn is ground, mixed with liquid and drunk among Hanoi’s elite. He developed his database of more than 1,000 rhino horn users by befriending members of golf clubs and luxury watch collectors over the past four years.

“I visited one of my friends and he organised a party,” Nam said of a gathering in Hanoi. “He told us that he had obtained a small piece of rhino horn and then he showed us and ground it into powder and shared it.”

A kilogram (2.2 pounds) of rhino horn can fetch as much as $60,000 on Vietnam’s black market.

“Rhino horn has been used in traditional medicine in Vietnam for centuries,” Nam said. The primary use is to reduce hangovers and fevers. Although not a traditional use in Vietnam, traders market the product as a cancer treatment and as an aphrodisiac “better than viagra,” Nam added.

In his research, Nam found approximately half of his surveyed consumers of rhino horn believe strongly in its medicinal effects. Conservationists have pointed out that a rhino’s horn is made primarily of keratin – the same material as a human fingernail.

But rhino horn is not only used medicinally, it is also used to curry favor and as a symbol of wealth for those able to afford the hefty fee.

“Some government officials are gifted rhino horn by business owners,” Nam said. “People in their networks use it as some kind of precious gift for building and extending relationships.”

Among the target rhino users in the country – rich, middle-aged individuals – Nam sees very little stigma and a low perception of risk for using the illegal product. The government focuses on making big seizures of illegal wildlife products rather than seeking out and punishing consumers, he stated. The combined factors make lowering demand for rhino horn difficult.

“They are very senior and they are wealthy and they know how to mitigate risk. Imagine that a police officer is a rhino horn consumer,” Nam said. “No consumer has been caught and prosecuted. Each year they only focus on some large cases and then follow with reports and promotions in mass media about their achievements.”

Despite the existing barriers in the fight against wildlife crime in Vietnam, Douglas Hendrie, chief technical adviser for the anti-wildlife crime unit, ENV, points to the big steps the country has made in tackling the issue.

In 2005, the nonprofit set up a wildlife crime hotline where people across the country can report offenses to ENV, who notify authorities. In the hotline’s early days, Hendrie saw a reluctance from the country’s police force to pursue crimes related to wild animals. In the years since, Hendrie stated, “Vietnam has made unparalleled progress dealing with wildlife trafficking.”

“I can remember in 2005 you’d call up and say there was a gibbon or a tiger sitting in front of a cafe and law enforcement would respond saying, ‘Hey, it’s Friday afternoon, we’re going home.’ Those days are over,” Hendrie said. “They treat it as a serious crime.”

Hendrie, who has worked in conservation in Vietnam since the mid-1990s, is encouraged by the current responsiveness of law enforcement in dealing with wildlife crime and criminal prosecution acting as a deterrent for wildlife traffickers.

With the 2017 penal code pushing the maximum sentence for wildlife crimes, increasingly strict punishments have led to Toan’s 14-year sentence for trafficking 55 rhino horns. Since the 2017 law, four major wildlife trafficking kingpins have been taken down in Vietnam.

Yet the road to stricter sentencing for traffickers has not been easy, Ha explained. Nguyen Mau Chien, a major rhino horn trafficker, was sentenced in 2018 to just 13 months in prison.

Disappointed with the short sentence, ENV advocated to lengthen his jail time, which was increased by three months. Still not satisfied, they convinced the High People’s Court in Hanoi to retry Chien. In 2020, he was sentenced to 23 months of jail time for transporting wildlife and possessing prohibited goods – more than eight years short of the maximum sentence for his crimes.

Although the country has made headway, both Ha and Hendrie agree more needs to be done to find the crime syndicates behind huge rhino horn shipments as well as ivory, pangolin scales and tiger bones coming into the country. Generally, when large seizures of wild animal products are made, only individual and relatively unimportant players in bigger trafficking networks are punished, like Toan.

On 11 January, a shipment from Nigeria of 6.6 metric tonnes (14,550 pounds) of ivory and pangolin scales was seized at Tien Sa Port in the coastal city of Danang. No arrests have been made but an investigation is underway.

“We should not just stop with the seizure, we should not just stop with the small fish,” Ha said. “What we should do from that seizure is to follow the small fish to identify those behind big shipments to finally take down these criminals. That’s when we will have a positive impact on wildlife.”