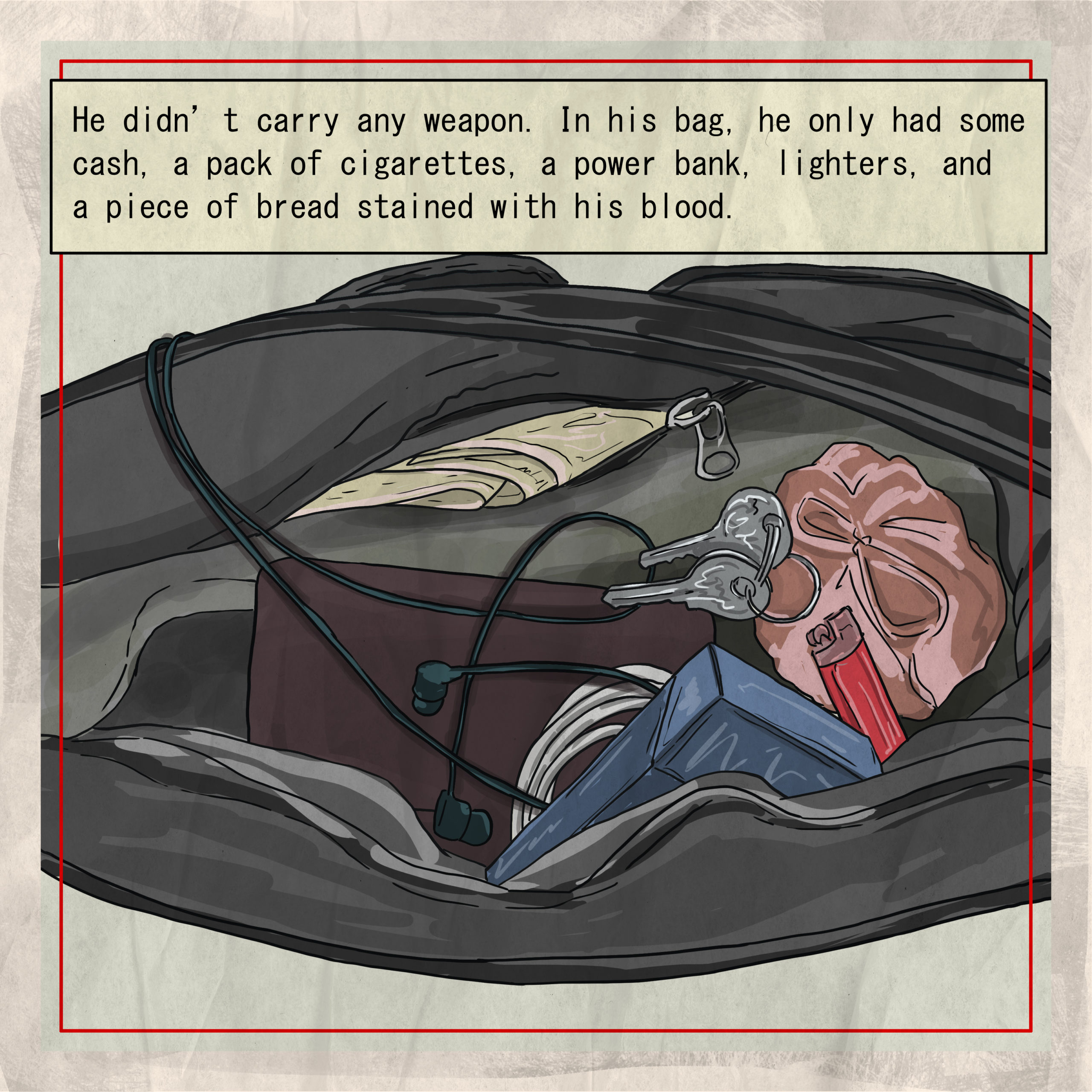

Before the Burmese network engineer-turned activist Nyi Nyi Aung Htet Naing became yet another post-coup headline, he carefully packed a bag for a day of protesting with the bare necessities: A power bank, a piece of bread, some cash, lighters and cigarettes.

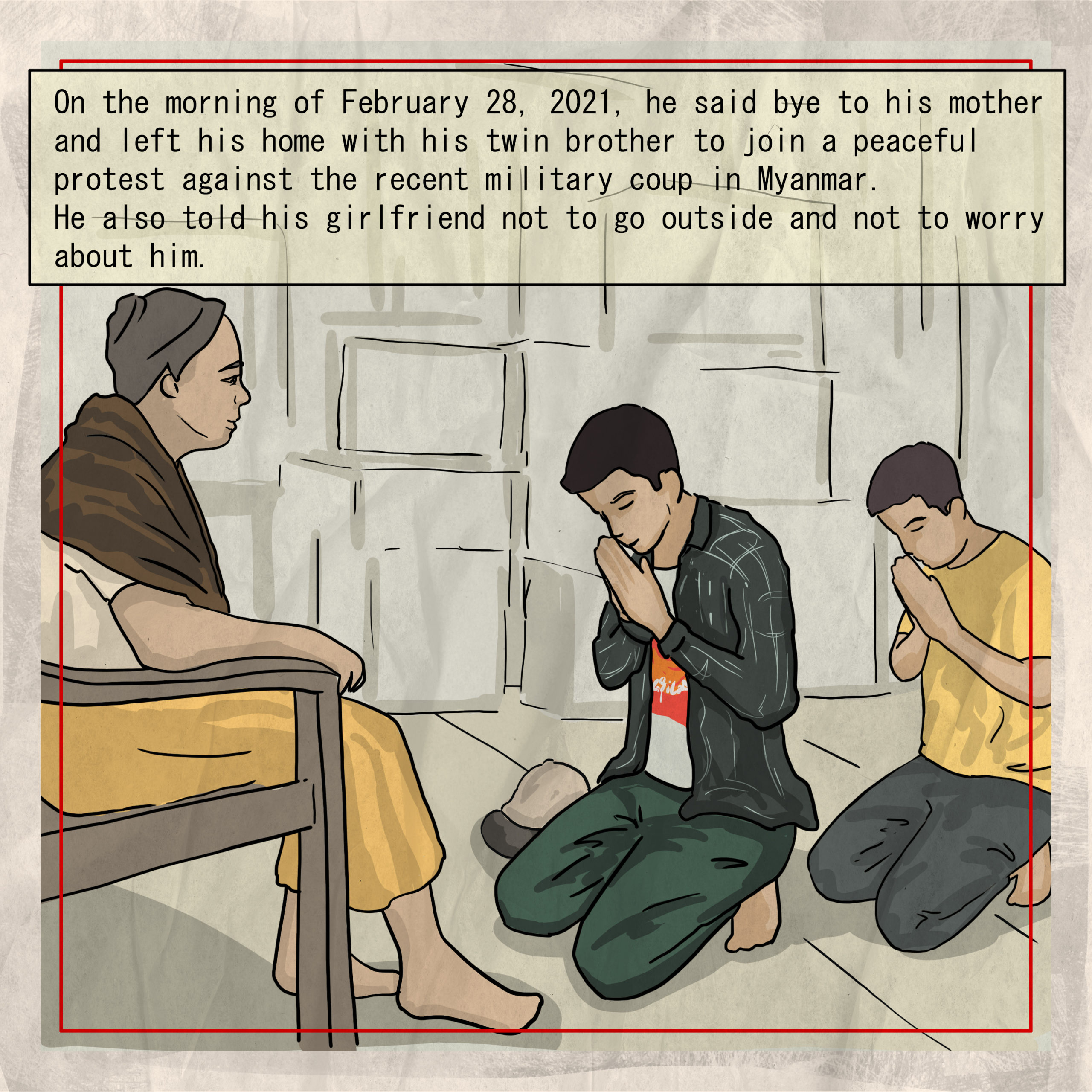

On February 28, he said goodbye to his mother and twin brother before going out to protest. He told his girlfriend not to worry about him, to stay inside. Just hours later, he would be killed by the Myanmar military.

These are the moments Singapore-based animator Kaung Thant thinks about at length before he begins to draw.

“He went out in the morning and said bye to his mom. It’s just a line reading, but that line does not evoke your emotion that much,” said Kaung Thant, who drew Nyi Nyi in late March as part of an ongoing art resistance project titled Heroes Vs Villains. “With an art interpretation [it] will help, so people will empathise more with the victim and the situation.”

Nyi Nyi is one of 769 people killed by military and police in Myanmar since the February 1 coup. As the daily carnage in the streets has become the norm for those reading headlines, artists are finding a role in the protest movement by making sure the often-unsung heroes of the anti-coup resistance aren’t forgotten, using moving portraits and comic-style narratives to share stories of their lives.

Heroes Vs Villains is one such project on Facebook and Instagram now drawing the talents of different artists to the cause. Started in the weeks following the coup by New York-based financial analyst Kyaw and another Burmese friend, Thet, the project is aimed at ensuring the deceased don’t become just another statistic in the military’s violent crackdown. As suggested by the title, the comics project is also out to hold the ‘villains’ responsible for the deaths and expose them to international scrutiny.

With comic-style panels, Kyaw is connecting with artists to make the account a moving tribute to those who have been imprisoned, tortured and killed, as well as offering the international community a glimpse into life in Myanmar in a simple, relatable way.

“When someone gets shot, they just report the name and age, not their background,” said Kaung Thant. “I want everyone to know they’re not just bystanders.”

Art commemorating the revolution isn’t a new concept, but social and digital media allows artists to share their work more widely and easily than ever before. From the many painters and poets expressing what the protest movement means to them, to the Myanmar Poster Campaign, an Instagram account collecting spring revolution posters to spread awareness, activists have seemingly always found creative ways to process the movement around them.

Kyaw and a friend came up with their own idea in the early stages of the coup, inspired by other art accounts on social media remembering the deaths of those killed by police in his now-home country of the US. By providing artists with a script and photos, they’re putting a human touch to the headlines and hashtags coming from Myanmar. Using sharable comics, bright colours, and storytelling, they’re hoping these portraits will educate the international audience on history in the making.

“I feel like comic-style is a bit more suited for storytelling, and we’re doing this as a story, what happened on that day,” Kyaw said.

For Kaung Thant, the research beforehand is critical. These sorts of comics aren’t normally his style, but he said going through the story scene-by-scene creates a different experience of drawing and storytelling, which he tries to make very personal.

Nyi Nyi is dubbed ‘the one who asked’ in the eight-part story, as his final post on social media before he went out to protest that day asks “How many dead bodies [does the] UN need to take action?” On that late February day, one of the most violent since the coup, he was shot through the stomach before fellow protesters rushed him to the hospital, where he died shortly after.

“When they go out, they’re preparing for the war,” Kaung Thant said, who tries to make each slide personal through research of the person he’s drawing. “It’s how I would say bye to my mom, or something from research, something from video capture [of them], or reimagining it from different angles.”

For Myanmar-based artist Coco Hong, who goes by her social media name, it’s clear the power of art serves as a solace and a passion as she excitedly flips through her sketchbook to show past projects. When she saw the Heroes Vs Villains account, she immediately asked for a storyboard to begin drawing.

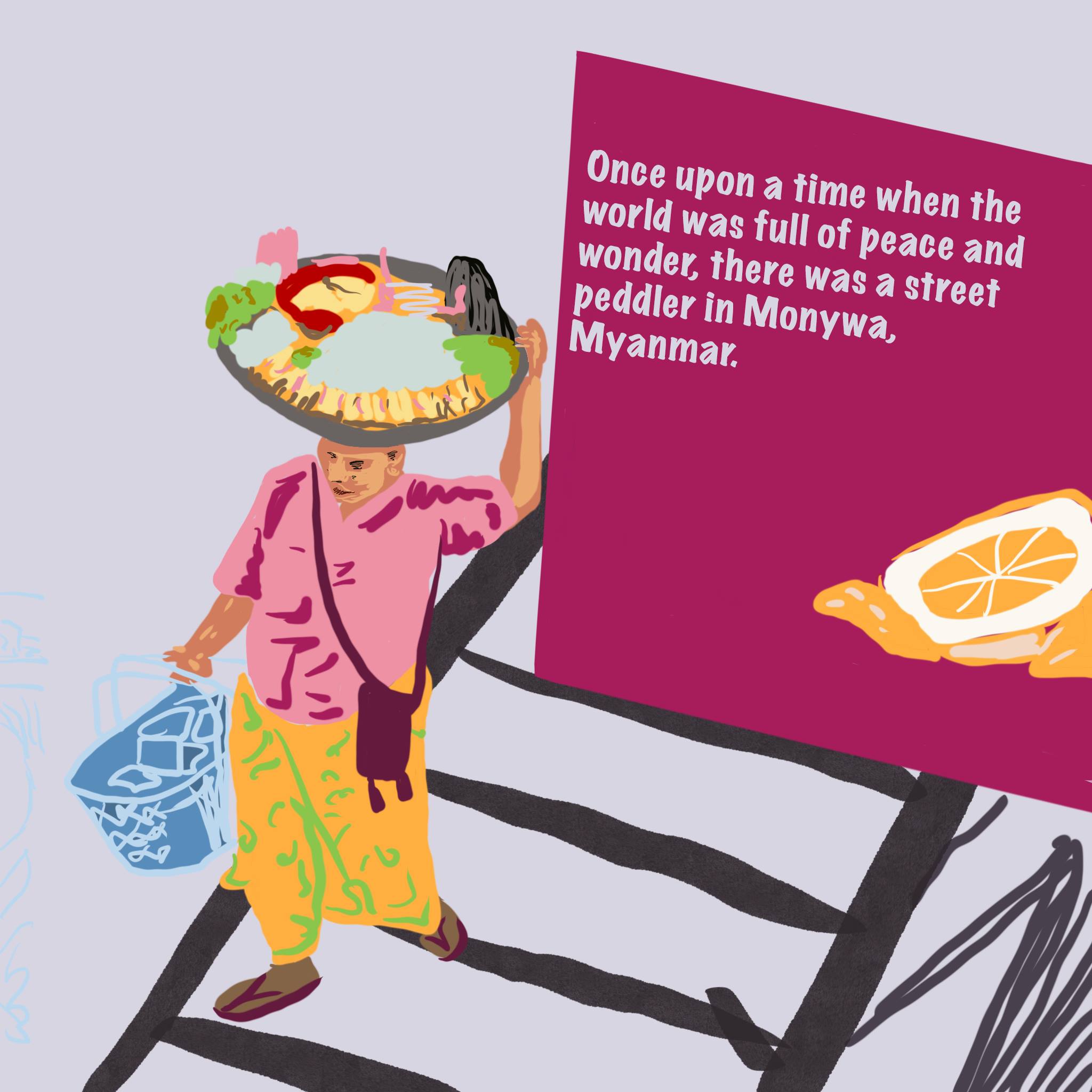

She understands the intentionality of portraying someone accurately, as she painstakingly used her eight panels to detail the bright colours of fruit peddler Daw Tin Tin Aye’s life. In a story widely publicised on social media, the fruit vendor from Monywa had been arrested in the early days of the coup and tortured by the military for donating her wares to protesters.

After the internet went out at 1am, I would download a podcast and listen to it while I’m drawing

‘The unbreakable’, as Daw Tin Tin Aye has been dubbed in the series, became an icon for not only Hong, but for many others throughout the country when her life was shared via social media. When Kyaw suggested Hong draw the fruit vendor, she found the story resonated deeply with her.

“I want it to be perfect, so I’d work on it little by little,” Hong said, explaining she’d work late into the night through the military’s ongoing internet outages. “After the internet went out at 1am, I would download a podcast and listen to it while I’m drawing.”

This drawing gave her a way to finally connect with the protest movement in a way that felt meaningful, where she was contributing her skills to help people gain a better understanding of the country. “There are so many artistic choices I made in these comic strips, so it just felt like I was creating something that other people could look at and learn about the coup from.”

In her silhouette-style drawings done in the bright, pastel colours, Hong said there were several details she had caught after spending weeks poring over her work. She says most often, friends pointed out Daw Tin Tin Aye’s smile, but for Hong, the humanising elements were the little details, like wearing the same shirt in two of the slides.

“A big takeaway that I wanted people to have from these drawings is that for a country that has so little, we do give so much,” Hong said. “Her smile is so genuine, she seems kind from the core. When I was making the colour palette, I wanted her slides to be bright, open and kind the way her spirit is.”

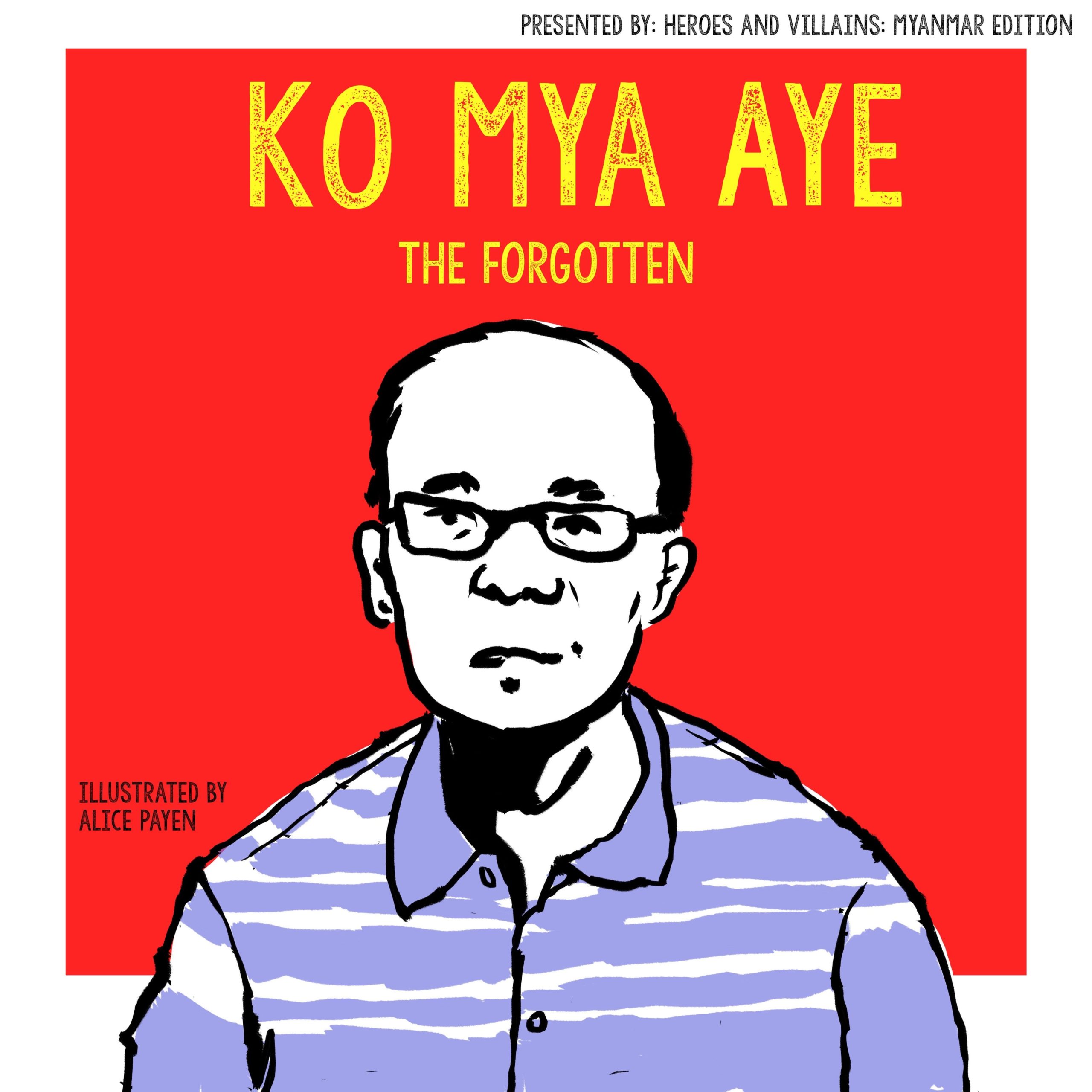

Daw Tin Tin Aye was eventually released, but the same can’t be said for Ko Mya Aye, a long-time pro-democracy activist and 8888 leader who was detained following protests in 1989 and 2007, and then again on the first day of the February 1 coup. No one knows the state of his well-being, or much other information since his arrest, a case all too familiar for Paris art student Alice Payen.

Though Payen herself isn’t Burmese, in early March her friend Han Thar Nyein, a Myanmar journalist and Kamayut Media co-founder, was arrested along with editor and founder Nathan Maung in the junta’s wider crackdown on independent media post coup. Payen took Han Thar’s case to Heroes Vs Villains to see if they could help raise awareness about it. While Kyaw worked on the script, Payen began to see parallels between her friend and the illustrations she was doing for Ko Mya Aye.

“When Han Thar’s lawyers were able to talk to him, he was tortured, he hadn’t eaten for days, he was terrified,” Payen said. “We’re all quite worried. That’s why it felt very emotional for me writing Ko Mya Aye’s story, because it’s the same kind of issue.”

Dubbed “the forgotten”, for his disappearance, Ko Mya Aye’s panels use only four colours in Payen’s characteristically abstract style, which she adapted to her Myanmar portraits.

“I usually have to take breaks because I feel very powerless,” Payen said. “We don’t know what is happening, we don’t know how they are, we don’t really know where they are, and we don’t really know what to do to help other than to talk about it.”

Emotions run high for artists detailing the pain of those living in the country, even for those living halfway across the world. For Hong, the process of drawing is soothing, but it also allows her to participate in the revolution in a way that feels valuable to her.

“There’s anguish, there’s stress, there’s hatred,” Hong said about living through the coup. “I think drawing is therapeutic for me, it’s just a good process.”

Art can transcend cultural barriers, and the simplicity of story-telling through comics is one everyone on the project hopes those living across the world can understand. Though Heroes Vs Villains only began sharing art on February 14, it has already gathered a following of more than 3,500 likes on Facebook. The enthusiasm Kyaw has seen from artists looking to contribute gives him hope the series will educate an international audience on not only Myanmar, but those individuals creating its history.

“When you look at historical figures, the student activists who have been protesting the junta over 20 years, they will definitely be remembered as the heroes,” he said. “There are definitely similar people as brave, as generous, as kind as the people we’re featuring. There are a lot of them.”

For all the heavy artillery and historic power the protesters lack, Hong is reminded of the movement’s creativity – which she says is one of its key assets – in the most unexpected places.

“On [military stations] MRTV or MWD, their graphics and their art on whatever it is, there are so many mistakes, it’s so outdated,” Hong said. “They have power, they have weapons, they have money, but they don’t have our art, they don’t have our brain, they don’t have our hearts.”