The president of the Philippines has entered his final year in office. Southeast Asia Globe analyses whether Aquino has lived up to the hopes of his nation

“If no one is corrupt, no one will be poor.” That was the slogan of Benigno Simeon Cojuangco Aquino III’s successful 2010 presidential campaign that thrust him to the nexus of Philippine politics. Reform was his watchword.

The country’s new president rode in on a gilded tide of hope, burnished by his deep roots in the country’s politics. His great-grandfather and grandfather both served as politicians. His mother, Corazon Aquino, was president from 1986 to 1992, propelled into the presidency in the ‘people power’ revolution that ousted the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. His father, Benigno ‘Ninoy’ Aquino, was a senator and much-loved leader of the movement against Marcos. He was shot dead at Manila airport in 1983 on his return from a period of self-imposed exile.

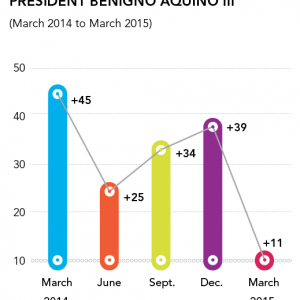

Since his election, though, history has been disregarded and Aquino has had to face the full scrutiny of the public. As he enters his last year in office – there will not be any further spells as presidents can only serve one six-year term – his approval ratings have tanked. A survey in March, published by BusinessWorld, a Philippine business newspaper, found that the net satisfaction rating for Aquino’s government had dropped by 15 points from plus-34 in December to plus-19. The survey also found that just 48% of Filipinos said they were satisfied with the Aquino government’s performance, down from 58% in December.

It all started well enough. Early on Aquino managed to usher in some substantive reforms on reproductive health – no mean feat in an overwhelmingly Catholic country – and excise taxes. However, since then, according to John Sidel at the London School of Economics, “it has been downhill: scandals, natural disasters, deadlock and little progress on any front”.

Indeed, the promised drive against corruption has seen scant movement and has mainly been used to weaken the opposition, said Ramon Casiple, executive director of the Institute for Political and Electoral Reform, based in Quezon City in the Philippines. “It is proving to be a more traditional presidency, bereft of the lasting reforms that his administration started with,” Casiple said.

Accusations of political corruption in various government agencies have surfaced, with the resignation of the customs commissioner and his replacement by a member of the Liberal Party – Aquino’s

own party – who heads a private brokerage business being a prime example.

“[Aquino] could have started the necessary political reforms to lessen the pervasive traditional politics of patronage based on elite political families and dynasties,” said Casiple. “He is zero on this score.”

In the president’s defence, however, there was a lot to clear up from the previous incumbent and her coterie’s spell in office. “He spent much time in his first year in office cleaning up the mess – and clearing out the human garbage – left by the preceding administration of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo,” said Sidel.

There may also be a more subtle, but nonetheless significant, legacy of Aquino’s time in office. The president is still seen as squeaky clean by many, and the fact he has set up a truth commission to tackle allegations of electoral rigging and widespread graft in his predecessor’s administration has met with approval.

The upshot of this is that the president has changed the anti-corruption agenda in two ways, according to Michael Johnston, a professor of political science at Colgate University in New York. Firstly, any candidate that succeeds him will “sense a great deal of pressure to do more than just issue vague proclamations regarding reform”, as was the norm pre-Aquino. Secondly, he has raised expectations. The public is no longer hesitant to openly criticise politicians, and the issue of corruption “has been re-framed from ‘hopeless’ to being a pressing priority on which action can be taken”.

Meanwhile, Aquino’s tenure has undoubtedly coincided with enviable economic growth, with GDP levels rising from $168 billion in his first year of office to a little more than $272 billion in 2014, according to World Bank data. For Johnston, this upward trend has demonstrated the value of strengthening the country’s institutions. Aquino can claim some credit for his macro-economic management as well as pushing through two key sets of legislation in healthcare and education.

The healthcare bill ensures that citizens have access to reproductive health information, services and family planning. The education law has made it mandatory for schools to offer kindergarten and grades 11 and 12 in both public and private schools – levels of education that did not exist countrywide previously and that brings the Philippine system in line with countries such as the US.

However, the president cannot take complete credit for these changes – all of them were started during the administration of Macapagal-Arroyo.

And, crucially, however vibrant the economy, most Filipinos have watched as the prosperity once again passes them by. “The ones who benefited are the rich, particularly the economic leaders who supported his candidacy,” said Casiple, pointing to the lack of higher wages for most citizens.

A significant millstone around the neck of Aquino and any future presidents is the imposition of a one-term limit. This makes even the most effective president a “lame duck” from the outset, according to Johnston. “Even in mid-2014 some reform proposals I’m familiar with were running into headwinds because more and more people already had their eyes on 2016 and beyond,” he said.

One area in which Aquino may be able to make his mark is in the push to end the long-standing conflict between the government and separatist Muslim rebels in the country’s south. In March 2014, a peace deal titled the Comprehensive Agreement on Bangsamoro was signed between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the largest rebel group in the region. Even with the agreement in place, a botched operation in January to arrest some MILF rebels still opposed to the treaty ended up with 44 commandos, along with 23 rebels, dead. Aquino has faced much flak for the operation’s failure.

“His peace talks with the MILF have produced a peace agreement, but there is, as yet, no reality of it on the ground,” said Casiple. Furthermore, the agreement has so far failed to persuade another rebel group, the Moro National Liberation Front, to agree similar terms – something Sidel feels Aquino could have pushed harder for. Even so, the president can at least take some credit for reducing the levels of conflict, violence and displacement in the southern Philippines.

As Aquino enters his final months in office, he certainly has some way to go if he is to leave a lasting legacy in the manner of, say, Roosevelt’s New Deal or Tony Blair’s peace agreement in Northern Ireland. “As of now, his achievements cannot be considered permanent or lasting and may not be supported by the next president,” said Casiple.

***

Getting to know Aquino

Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino III was born on February 8, 1960, in Manila. He is the son of Corazon Aquino, who served as president of the Philippines (1986–92), and political leader Benigno Simeon Aquino Jr. In 1981, Aquino graduated from Ateneo de Manila University with a bachelor’s degree in economics and then joined his family in Boston where his father was living in self-imposed exile. In 1983, Aquino’s father returned to Manila and was shot dead at the airport.

The family returned to the country soon afterward, and the young Aquino worked there for companies including Nike Philippines, as well as the corporate non-profit foundation Philippine Business for Social Progress. In 1986 his mother became president of the Philippines and Aquino became vice-president of his family’s Best Security Agency Corporation.

In 1993, Aquino left that post to work for a family-owned sugar-refinery business. In 1998,

he entered politics as a member of the Liberal Party and served three consecutive terms as a

representative of the 2nd district of Tarlac province as well as concurrently serving as deputy speaker of the House of Representatives from 2004 to 2006. He resigned from that post before joining other Liberal Party leaders in calling for President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo to step down over accusations

of widespread corruption.

From 2006 Aquino served as vice-chairman of the Liberal Party and, in 2007, he made a successful bid for a senate seat. In September 2009, Aquino announced he would be running in the 2010 presidential race and won by a wide margin.

***

Action Aquino: From the crucial to the quirky, a selection of the president’s accomplishments

2012 Framework Agreement on Bangsomoro

A preliminary peace agreement signed on October 15, 2012, paved the way for the creation of an autonomous political entity named Bangsomoro, situated in a Muslim-dominated region in the southern Philippines.

Formation of a truth commission

The commission is investigating corruption allegations against the former president, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, particularly the alleged rigging of the 2004 presidential election, the misuse of state funds and graft in government contracts.

Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act of 2012

Aquino pushed through legislation that had been batted back and forth for a decade. Filipinos now have access to reproductive health information, services and care, all of which are necessary for planning and raising families responsibly.

Promotion of Filipino music

In August 2010, Aquino ordered media regulators to fully implement a 1987 executive order by his mother, President Corazon Aquino, that requires all radio stations to play at least four original Filipino compositions per hour.

No wang-wang policy

Strengthened an existing presidential decree that limits the use of wang-wang (blaring sirens) on vehicles to a limited number of senior officials. Aquino declined their use on his official vehicle, despite being eligible to use one.

***

“Drawing the line” – China’s moves in the South China Sea have incensed some Southeast Asian nations, and the Philippines’ foreign minister is getting right in the thick of it