In Singapore’s ongoing general election season, the political battlegrounds have shifted to remote settings as parties compete for the hearts, minds and votes of the electorate through telecasts and social media.

Much to the chagrin of rights groups, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong called for a general election on 23 June despite restrictive pandemic conditions. The prime minister reasoned that dissolving parliament and holding an election would “clear the decks” for a new five-year mandate.

As polling day dawns upon the city-state on 10 July, local media has been riddled with coverage of political constituency broadcasts, spotlights on candidates and e-rallies. But many parties have not enjoyed a smooth sailing campaign, even the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP).

The general election climate has taken an unprecedented shape amidst the economic and social effects of Covid-19. The rise of alternative media sources and increased media literacy has fuelled a savvier, more critical electorate and some of the most vociferous challenges leveraged against the ruling party yet.

With parties emerging battered and bruised after a brutal three-week campaign, the full impact of these factors on the final election remains yet to be seen.

Already, social media campaigns have shown the extent of their influence as Singapore’s election candidates are spotlighted and heavily scrutinised.

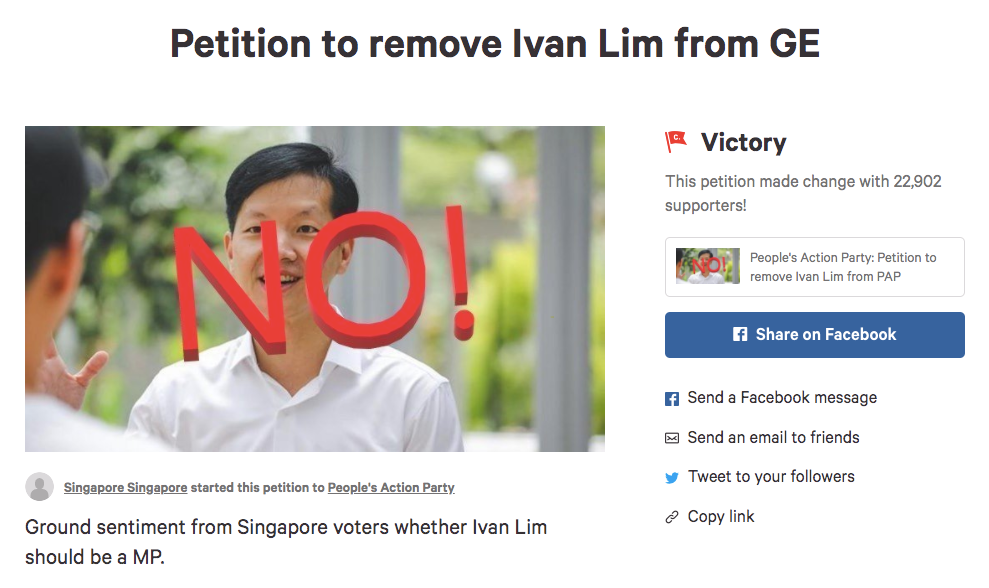

In late June, Netizens challenged and eventually ended the candidacy of one PAP candidate, Ivan Lim, after creating an online petition urging him to withdraw from the upcoming contest. The petition gathered more than 20,000 signatures after the public airing of personal anecdotes from individuals who had negative experiences with Lim in the past and felt he was ill-suited to run the political race.

Some of those anecdotes were based on his personal demeanour, pointing to allegedly elitist and arrogant conduct during Lim’s time in the army; others made unverified allegations Lim had been involved in a bribery case in Brazil while working for the oilfield company Keppel Offshore & Marine.

The online heat built into a wildfire and by late June pressured Lim into withdrawal from the race.

A pro-government political commentator and Singaporean researcher, who wished to go by the name Kong, believed the digital campaign against Lim’s candidacy “certainly sets a dangerous precedent for politics in Singapore”, adding that no one will be able to withstand such public pressure.

“The allegations were unverified but widely believed by the public.”

Kong said public opinion seemed to matter more to some than the truth. With the rise of more alternative media channels in Singapore, “cyberspace is often used for alternative perspective and sometimes ‘alternative facts’”.

But others within that independent media space offer a different perspective. Kirsten Han, a local independent journalist, said it was interesting that the petition became the primary way for people to express their opinion on Lim. Lacking official channels to openly express discontent with politics, Singaporeans are creating their own means to do so online.

“To express this democratic voice, it had to happen outside the electoral system itself,” she pointed out, emphasising the need to be discerning with inaccurate and unverifiable information more prevalent than ever in Singapore’s highly democratised online space.

Natalie Pang is a senior lecturer and researcher at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy who studies digital citizenship and the role of social media in political participation.

She chalks up the main difference between the past election to the current to digital natives becoming more aware of potential echo chambers, silos in which consciously or subconsciously users confirm their own biases.

Pang has observed youths increasingly turning from blog posts to platforms like Instagram, with their increased reach and interactive potential, to post non-partisan content to educate others about elections and policies.

“These are not necessarily anti- or pro-establishment,” Pang said. “Mainly they have got to do with understanding constitutional rights and civic interests.”

Besides the social media world, the shift to an online campaign has resulted in alternative, non-mainstream media channels playing an increasingly prominent role in influencing discourse. Kong commented on how the city-state’s media landscape has evolved and changed over the years.

“Mainstream media does not actually hold the monopoly over viewership, and the reporting of opposition activity in mainstream media is actually quite prevalent in the current 2020 general election,” he said.

What the government tries to do is fund these alternative media channels so they have control over it

However, Kong observed social media tends to favour the opposition as dissenting voices tend to travel further.

“While it is unclear if [what one sees on their social media] represents the views of the ground, it can definitely sway opinions.”

Thum Ping Tjin, the managing director of alternative new site New Naratif, pointed out the government’s control over Singaporean media has never been “obviously authoritarian in the sense that it eliminates alternative media altogether”. However, even with some plurality of voices, their control remains subtle and pervasive.

“What they try to do is fund these alternative media channels so they have control over it,” he said.

Citing burgeoning Singaporean digital platform Mothership as an example, he went on to explain these media sites subsequently become reliant on the government for funding, meaning there are “lines that they don’t dare to cross”.

The changing nature of online discourse during this campaign has been further highlighted by two prominent cases in recent days, against both government and opposition candidates.

On 5 July, an as-yet unnamed tipster filed a police report against opposition party candidate Raeesah Khan of the Workers’ Party for comments she had made on social media allegedly sowing racial enmity – a social and political landmine in the highly multiracial city-state.

According to a police statement, Khan commented that Singapore disproportionately jailed minorities and harassed mosque leaders, but let corrupt church leaders walk free. The report was met with an outpouring of support for the candidate, with hashtags like #IStandWithRaeesah and a Facebook group on her behalf gaining traction.

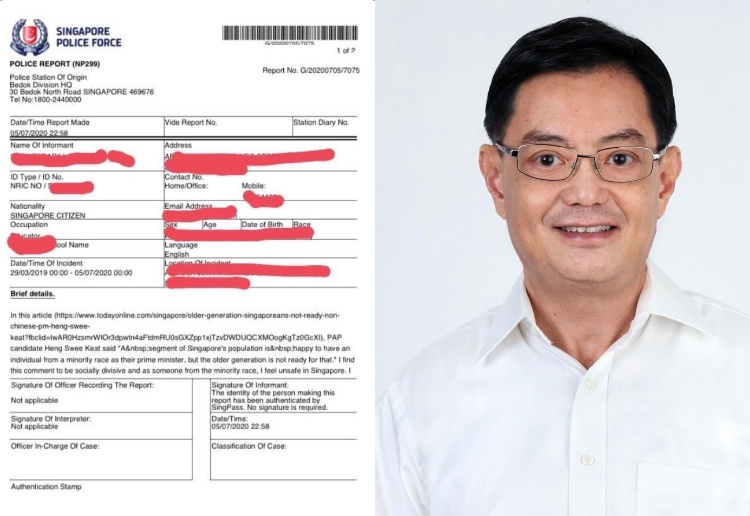

On the same day, an individual also filed a police report against Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat of the PAP for allegedly also sowing racial discord following his declaration in March 2019 at the Nanyang Technological University that older Singaporeans are not ready for a non-Chinese Prime Minister.

A flurry of similar complaints later unfolded in a tit-for-tat as Singaporeans started filing police reports against other citizens for alleged racism, such as local influencer Xiaxue and the tipster who lodged the initial report against Khan.

The case against Heng was quickly closed as the Attorney-General’s Chambers this week ruled that no offence was committed, but this unprecedented move in Singapore’s political landscape, the filing of a report against a member of the PAP, was symbolic of the shifting tides.

On this matter, Kong thinks it is clear that “there is no consensus on what racism is” and asserts that, moving forward, both government and society must redefine the set of principles governing social norms.

“As a society, we really need to confront about how we talk about race,” Pang said. “It also shows that, for those who feel helpless, they will look for other ways to respond or express their dissent, such as official police channels.”

However, Pang also stressed the importance that people use these tools the right way.

“We should also stop to think if this is what we want our police institutions to be busy with. As a society, we really also need to prioritise having hard conversations and how we express these dissent and actually talk to each other.”

As Singaporeans’ political sentiments spill from online avenues to more official levers, Thum chalks this year’s rising tensions up to the fact Singaporeans only get to experience a sliver of democracy once every few years.

“Singaporeans get nine days, basically two weeks of democracy every five years. And even if that is very little during election time, we have so much more power – because there is no government in that interim as the ministers don’t occupy the offices yet,” Thum said.

“What you see every five years is that all the frustration from these years gets compressed into this window of time – and it really culminates into a strong backlash.”

In previous years, rallies were at the heart of Singapore’s elections. A hubbub of infectious energy and chutzpah, rallies were the strongholds of political parties who wish to woo potential voters and champion their causes.

The absence of rallies this year due to the pandemic meant a massive shift toward online campaigning, as well as both live and pre-recorded telecasts.

Kong noted that while online rallies rise above geographic boundaries that restrict the reach of past physical rallies, bringing campaigns to a wider audience, the pitfalls of solely online platforms include the threat of a far-reaching and immediate dissemination of false information.

“The damage will be done before any corrections [can] be made,” he said.

Opposition party rallies are massive. And this makes people realise every time – ‘Oh, I am not alone’, because this fear is very, very real in Singapore

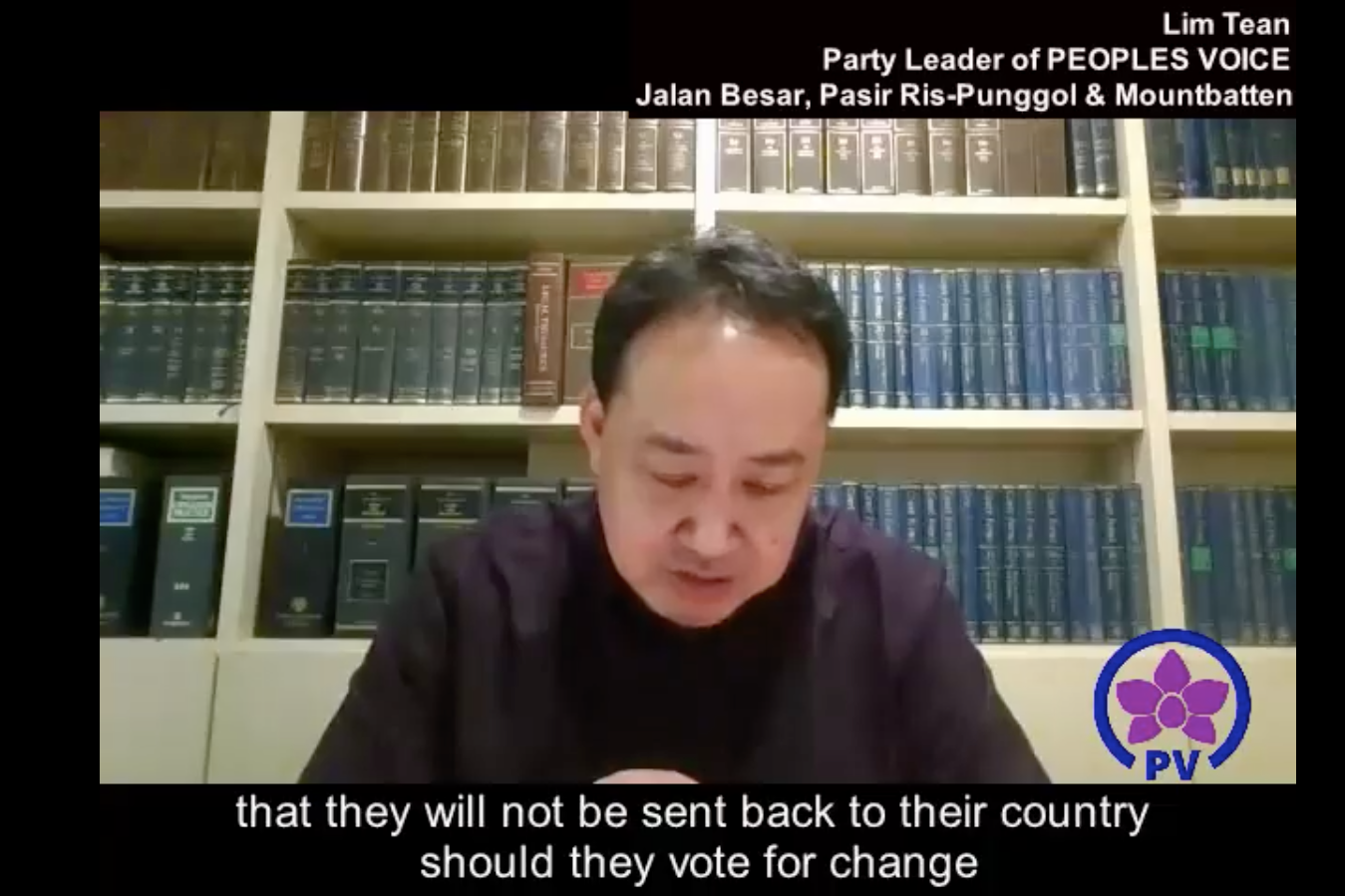

Thum is concerned the new format could disadvantage opposition parties, as they traditionally relied on in-person rallies. He also explained that being in the presence of a rally surrounded by like-minded people counterbalances the apprehension that opposition supporters may feel in Singapore – a country long-dominated by the ruling PAP – in choosing to take a differing path from the majority.

“Opposition party rallies are massive. And this makes people realise every time – ‘Oh, I am not alone’, because this fear is very, very real in Singapore.”

Han muses on her past experiences with physical rallies as a fertile site to sift out opinions on the ground. She drove home the point that social media has now become an increasingly important gauge of public sentiment as such limited physical campaigning can be done.

“However, at the same time I am also hesitant about trying to derive what the exact ground sentiments are through social media, because it’s not actually the ground,” she said. “Perhaps it might become a little bit more reflective of that when more generations are digital natives, but not now.”

That being said, Han cited some benefits that could come with an election season that had no choice but to go online. Broadcasted campaigns and live question-and-answer sessions are more conducive for facilitating political discussions and deeper conversations than what physical rallies allow, what with all the cacophony and blaring loudhailers, she believes.

“I don’t think they would be able to address these issues with such nuance in a rally,” she said. “In previous general elections, everyone was obsessed with going to rallies and planning which ones to go. I don’t remember that being such a loud call for the parties’ manifestos and bothering to understand what they champion in more detail.”

As Singaporeans wait eagerly for electoral results, what is equally important is how the country goes forward from there after forming a new parliament.

Pang believed that even though an increasing number of youths are claiming a stake in digital citizenship and heightened civic literacy, it’s still vital to learn how to critically analyse all kinds of information and hold civil conversations about certain issues.

“We can try to agree to disagree – I know this is a cliche statement and often said in every election, but in practice it is not easy,” she said.

“[With the Khan and Lim incidents] this election showed me that as a society, we really need to learn more in terms of how to do that.