Inside the 'World’s Saddest Zoo'

Home to a tragic menagerie of primates, tropical birds and reptiles, the infamous Pata Zoo sits atop an ageing mall in Bangkok. Its enclosures are stark and dirty, its long-term residents depressed and listless – yet this condemned zoo continues on

Words and images by Mailee Osten-Tan

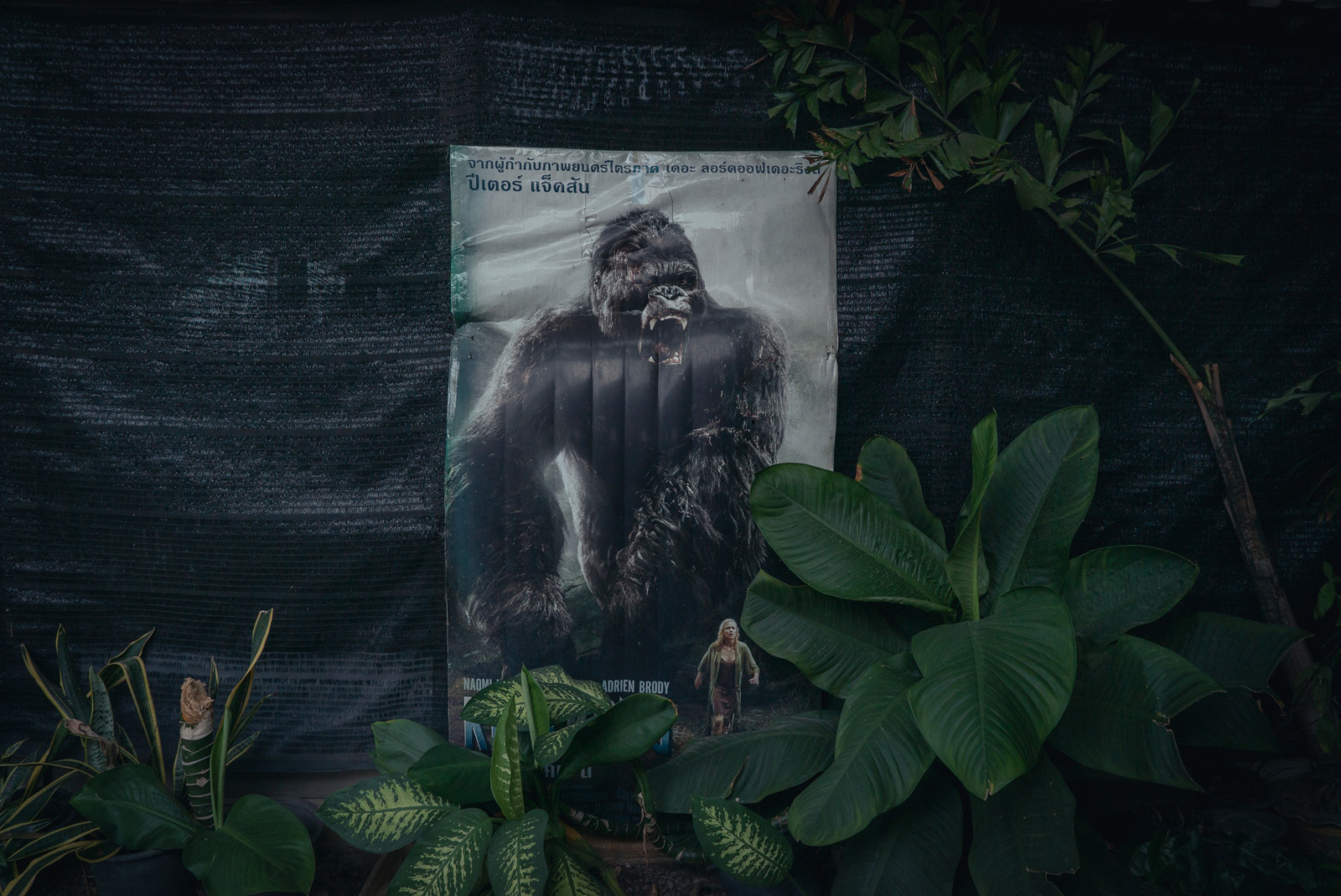

In the 2005 film King Kong, the legendary ape is shackled and presented on a stage for the thrill of a gawking Broadway audience. For those watching the film, to see a great beast with his intelligence and anthropomorphic qualities rendered powerless carries a sense of poignancy. We turn from monster to man and man to monster, presented with the task of deciphering which from which.

On the rooftop of an ageing Bangkok shopping mall selling clothing out of bargain bins, a neon pink sign points towards a 200-square metre compound: King Kong, this way. A poster of the 2005 remake is tied to a nearby piece of tarpaulin. To the right is a giant plastic rendering of a gorilla’s palm ready to receive eager children and the snap of smartphone cameras wielded by equally eager parents.

But the gorilla inside the privately owned Pata Zoo, housed on the 6th and 7th floors of the Pata Pinklao Department Store, is not the cinematic monster. Her name is Little Lotus, or Bua Noi in Thai, and she is lying on her back on the concrete floor, staring listlessly at the sky.

There is a thick, musty smell – something half-way between a humid hospital corridor and a neglected cat litter tray

Doubly sealed off with glass barriers and black, metal bars, her compound contains nothing more than a few car tires to amuse her. At her feet is a small, white, box carton of milk – well squeezed. She has lived in the zoo for over twenty years. Unlike Kong, who rips free of his chains and charges into the streets of New York, she is long institutionalised.

Cited as the last gorilla in Thailand, Bua Noi is Pata Zoo’s most famous resident. But the zoo also houses other animals on its two floors, both caged and uncaged; fearless rats run openly down the gutter drains. A jerboa paces in a small tank, the rodent’s long legs clearing a track in the sawdust, stopping only to paw against the dirty glass.

An orangutan urinates through the fence into the visitor footpath. Another blows raspberries. Another is face down, spread-eagle on the floor of its enclosure. There is a thick, musty smell – something half-way between a humid hospital corridor and a neglected cat litter tray.

The animals exist to perform for an absent audience. Pata Zoo once boasted interactive magic and animal shows on the weekends, but on a recent Saturday afternoon when these photographs were taken, visitors were few and far between, the rows of collapsible chairs in the main room gathering dust in darkness. These images capture but a mere fraction of the desolation and eeriness of the atmosphere inside.

Tourism in Thailand, unsurprisingly, dropped by 75% in 2020. Among many businesses suffering in the coronavirus pandemic’s wake, the lucrative animal tourism industry in Thailand has also taken a hit. Pata Zoo is no different, but even before the falling numbers of Covid-cautious visitors, this sense of abandon did not go unnoticed.

In 2014, animal rights activists submitted a petition of 35,000 signatures to Thailand’s Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation calling for the zoo’s closure. The petition was dismissed.

In 2015, authorities confirmed that the zoo had broken several laws and ordered for Bua Noi and the other animals to be removed. The zoo pledged to relocate Bua Noi from her rooftop enclosure to the ground within five years, but no action has yet been taken.

In December 2020, the zoo received international scrutiny when the singer Cher published an open letter to the Thai Minister of Natural Resources, Varawut Silpa-archa, appealing for the animals to be freed. Meanwhile actor Gillian Anderson and animal rights organisation PETA dubbed Pata ‘one of the saddest zoos in the world’.

In the face of this highly publicised criticism, Sky News reported that the owner of the zoo and shopping mall, Kanit Sermsirimongkol, had dismissed claims of animal cruelty and cited financial difficulties brought on by the pandemic as the reason behind scrapping plans to build Bua Noi new facilities. He has refused to allow for her or the other animals to be relocated to a sanctuary.

Now more than ever, public concern has been raised about the lack of mental stimulation the isolated animals are receiving without even tourists to provide some level of observable interest.

To see this real-life Kong in Pata Zoo today harks back to a familiar sense of poignancy. People who struggled through many months of lockdowns can potentially empathise with animals that share 97% of their genomes kept in solitary confinement their whole lives.

Recent reports claim that the zoo’s license expired in June 2020, but is still pending renewal. Whether granted or revoked, the world’s stage is watching.

![[Photos] Inside Pata, the ‘World’s Saddest Zoo’ in Bangkok](https://southeastasiaglobe.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/d387b0a7.jpg)