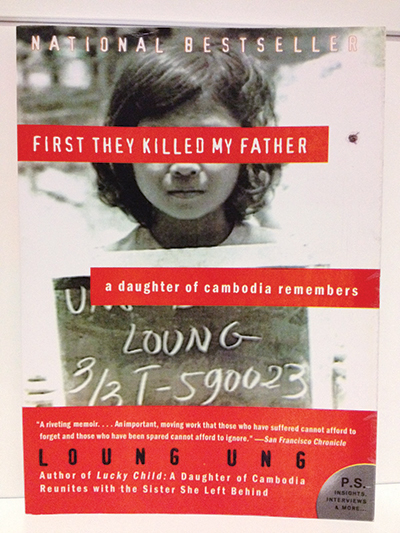

In the early pages of Khmer Rouge survivor Loung Ung’s haunting memoir, First They Killed My Father, the five-year-old narrator provides a brief yet vivid snapshot of Phnom Penh in the early 1970s, just before the ultra-Maoist Khmer Rouge regime seized power and emptied the city of its inhabitants.

The childlike prose paints Ung as the boisterous and curious tomboy in a loving, affluent family of seven children – playfully scolded by her mother and adored by her father, a police commissioner in the Lon Nol government. Commenting on Ung’s mischief in the book’s first chapter, her father tells his wife that “the fact she gets herself in and out of these situations gives me hope. I see them as clear signs of her cleverness”.

By the end of the book, the poignancy of this characterisation is revealed: these are the traits that in the following years helped Ung survive displacement, forced labour, starvation and the deaths of both of her parents and several of her siblings.

Even as, several years later, she is trained as one of Pol Pot’s child soldiers, the nourishing memories of Ung’s early life stay close to her. Through her eyes, readers are taken on a heart-wrenching journey of the author’s transition from a cheerful city girl to a nine-year-old orphan of Cambodia’s killing fields.

Ung later escaped with her older brother to a Thai refugee camp and eventually to the US. Published in 2000, First They Killed My Father exposed its readers to the atrocities suffered by Cambodians during the nearly four years that the murderous regime was in power. The book was an instant bestseller and has since been published in 14 countries.

Ung’s story has been thrust into the international limelight once again when Hollywood star Angelina Jolie’s highly anticipated film adaptation of the memoir screens for the first time at the Terrace of the Elephants, located within the Angkor Thom temple complex, just outside of Siem Reap.

Filmed between 2015 and 2016 in Khmer with an all-Cambodian cast, it is the largest, highest-profile movie ever made in Cambodia. Bophana Productions – a local company founded by Oscar-nominated film director Rithy Panh, who worked as First They Killed My Father’s co-producer – reportedly employed more than 500 Cambodians behind and in front of the cameras, many of whom were survivors of the genocide or survivor’s children.

Scenes set in Phnom Penh were shot mostly in the sleepy town of Battambang in Cambodia’s northwest, while others were shot around the rippling rice fields and dusty villages of Siem Reap, including some inside the ancient, crumbling Angkorian ruins.

Ung was played by first-time actor Sareum Srey Moch (on set, Ung nicknamed her ‘Mini-Me’), while her father was played by writer, artist and interpreter for the Khmer Rouge tribunal Phoeung Kompheak. Her mother was depicted by Sveng Socheata, a well-known Cambodian actress.

At the time of publication, details on the premiere remained scarce. Netflix representatives and the film’s production crew did not respond to requests for comment from Southeast Asia Globe, but a source working closely with the event confirmed it would screen on February 18, with a string of subsequent shows to be held shortly after in rural Cambodian towns and villages.

First They Killed My Father will then be released globally in September through Netflix, the world’s largest online streaming platform. In an interview published in the Guardian in late January, Jolie said she had approached Netflix directly because she “wanted to make the kind of film where I don’t have to compromise and put a famous Chinese actress in as the mother, or make it in a different language in order to get people in the theatres on the first weekend”.

The same year that Ung penned her book, Jolie’s love affair with Cambodia began. The action blockbuster Lara Croft: Tomb Raider had the actor scrambling over giant, tree-covered stones and sipping tea with monks outside Angkor Wat’s lotus-shaped spires. Jolie and the crew set up base in Siem Reap, less than 10km from the ancient ruins, and she soon became immersed in a society that was still reeling from a decades-long civil war. Tomb Raider was perhaps also the catalyst for Jolie’s humanitarian work: she soon returned to Cambodia, working with the UNHCR and later became one of its goodwill ambassadors.

After Jolie purchased a 60,000-hectare national park near the Cardamom mountains and turned it into a protected wildlife reserve in 2003, King Sihamoni awarded her Cambodian citizenship in recognition of her community development and conservation work. In 2006, Jolie and her then-husband Brad Pitt founded the Battambang-based Maddox Jolie-Pitt Foundation, a community development and environmental NGO.

It was around the time of Tomb Raider that Jolie reportedly first read Ung’s memoir; soon after, she made contact with the writer and they travelled through Cambodia together. It was this trip, Jolie told the Guardian last month, that spurred her to adopt seven-month-old Maddox Chivan. In the lead-up to the adoption, she said, she and Ung discussed “what would be important, to make sure he always knew about himself”.

Now, years later, she will be hoping that her adaptation of Ung’s book puts the country in the spotlight once more. It should be helped by the fact that Cambodia’s film industry has been undergoing something of a renaissance, four decades after Khmer Rouge purges wiped out most of the country’s artists, musicians, actors and filmmakers. A film commission has been established, which encourages local productions and sells Cambodia as a filming destination to foreign productions. Young auteurs such as Kavich Neang, Sothea Ines and Davy Chou have screened at big-name film festivals around the globe, while Panh’s Oscar nomination provided the industry with a huge boost.

While it has been suggested that the young film community felt they were in a better position to tell the harrowing stories of their elders than a foreigner, those Southeast Asia Globe spoke to thought that having Jolie in the director’s chair could be positive for the country’s film scene.

Chou, a French-Cambodian filmmaker whose first full-length feature, Diamond Island, won the screenwriter’s award at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival last year, described it as an “important moment” for local film.

“It looks like nearly all local technicians were hired at one point on the film, working with experienced Hollywood technicians and getting to learn intense and challenging processes, which most had not experienced before.

“This is obviously an amazing opportunity to push the Cambodian film industry standards and quality even higher. The first [trailers] look impressive, and Jolie’s name will bring much attention to the film and it will then bring awareness about the Khmer Rouge. That’s an important thing. Cambodian directors will have more opportunities in the future to tell their own stories of our history,” Chou said.

Sothea Ines, who was awarded the top prize at the 2014 Tropfest Southeast Asia short film festival, said she was excited after viewing First They Killed My Father’s trailer, despite hearing that the majority of the crew’s heads-of-departments were foreign. “It would be hard for a Cambodian director to get the kind of financing needed for this huge production and bring in such a professional crew,” she said.

Yet the central purpose for making the film is the hope that it may have some remedial effect on Cambodians still suffering post-traumatic stress disorder. Co-producer Panh has dedicated his life to ensuring Cambodia’s younger generations do not forget the past. In the Netflix teaser for First They Killed My Father, he said: “In order to mourn, we must speak. It’s the possibility of using creation to reconstruct ourselves. Telling a story is also mourning… it’s moving on.

“It goes further than a film, actually… What we are trying to do, it’s a kind of a bridge between our former selves and tomorrow’s generation. Those who left, those who’ve gone, us survivors and tomorrow’s generation.”