From English Romanticism to politicised Marxism, tracing the timeline of poetry in Myanmar

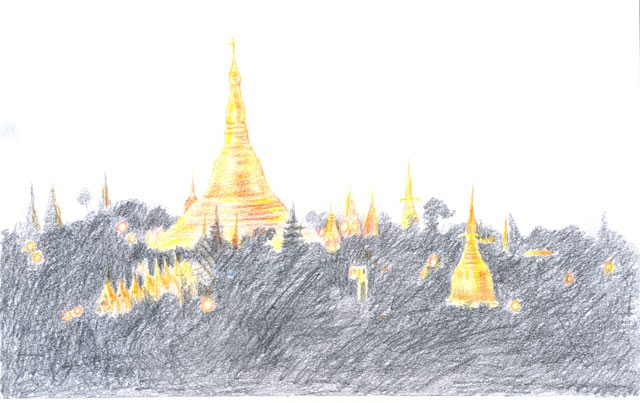

By Nathan Thompson Illustrations by Chea Vuthea

There was a revolution in poetry in the early 20th Century. In the West, poets began to do with verse what Picasso was doing with the portrait. Or what Duchamp was doing when he submitted a supine urinal to the Society of Independent Artists. The result was Modernism. And it caught on. As Gertrude Stein wrote in 1924: “The difference is spreading.” And spread it did. All the way to British-ruled Burma.

In Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, poetry is sacred. The earliest poem there is carved into a stone dated to the 9th Century AD. Over the centuries, traditional poems were composed on themes of patriotism, love and religion. During British rule, political dissent brewed in the poetry people recited. Modern poetry in Myanmar began in the early 20th Century. Influenced by translations of the English romantics and the great Indian poet, Rabindranath Tagore, Khit San, or ‘experimental poetry’, began.

Khit San used a traditional structure – like a Myanmar version of the English sonnet – but rejected the grand themes of traditional verse in favour of the language of everyday experience. Like modernism in the West, the implicit critique of traditional verse in Khit San made it impossible for poets to unselfconsciously write traditional verse any more. The only way forward was further innovation. All subsequent movements in Myanmar poetry are a response to Khit San.

The first break from Khit San happened after World War II. Marxist poets derided Khit San as bourgeois and lifeless. For them, poetry was a weapon of the people against the ruling class. Khit San poets flew the banner of ‘art for art’s sake’ while the Marxist poets cried ‘art for the people’s sake’. The Marxists named their poetry New Writing. Dagon Taya, Myanmar’s literary godfather, was one of the first writers to introduce the communist realism associated with new writing. He and his disciples loosened the tight rhyme scheme of Khit San, imbibing each line with leftist ideology. Anything that could not be easily understood by uneducated people was rejected.

The Khit San poets fought back, accusing the Marxist poets of sacrificing aesthetics for politics and turning poetry into a soapbox. The socialist coup of 1962 put an end to the squabbling. Now a single party state, political poetry was banned and Dagon Taya imprisoned. After his release, Dagon Taya went into self-imposed exile after refusing to bed down with the new regime. “You may do away with rhyme, but not ideology,” he said.

Myanmar became a hermetic state. University campuses had no exposure to foreign literature until linguist Maung Tha Noe released an anthology in 1968 containing translations of TS Elliot and Mayakovsky. The result was explosive. Young poets read the book to tatters. They began to write free verse in the local language. Moe Wei, as it became known, rejected the traditional rhyme schemes used by Khit San and new writing and mimicked instead the clipped rhythms of street speech. Poems that criticised the government and Vietnam War were published in photocopied journals distributed secretly on university campuses.

In 1987, Burma’s ruler U Ne Win instigated radical economic policies. They contributed to the financial crisis of 1988, which led to flare-ups of disorder and violence. Out of the smoke and fire, the military seized power, sweeping aside the constitution in favour of military rule. In the decades following the 1988 coup, Myanmar stabilised and opened up to foreign trade, allowing small amounts of Western culture and ideology to seep into the consciousness of the country. Influenced by Western ideals of individualism and democracy, Khit Por, or ‘modern poetry’, began to fill poetry magazines. Publishing under pseudonyms, the Khit Por poets wrote to express themselves and their feelings but often found their work slashed by the censor’s marker. A few were imprisoned, with the most famous case being Saw Wai, who was arrested and imprisoned in 2008 for writing a slushy Valentine’s poem – the first letter of every line acrostically spelling the phrase, “Power Crazy Senior General Than Shwe”.

Khit Por poetry had two problems. The first was that its clear and distinct images easily fell foul of censorship. The second was that the movement fell into repetition and mimicry. “The focus on the poet’s emotion started to take its toll to the point that poets were reproducing the same emotions in the same ways so much so that an editor of a magazine wrote that poems were becoming almost identical,” said Zeyar Lynn, one of Burma’s most acclaimed contemporary poets, in an interview with Jacket2, a poetry magazine based at the University of Pennsylvania in the US.

In 2004, Zeyar Lynn began to translate the work of the American Language Poets. ‘Language poetry’ began in the 1970s and rejects the idea that language can refer to a reality beyond itself. Instead of describing events or feelings, language poets use novel, often nonsensical, combinations of words, letters and sentences to create something completely new. As poet Charles Olsen put it: “In dismantling the scaffolding [of language], we create a literature of ‘unreadability’ – that which requires new readers, and teaches new readings.”

It was the perfect antidote to Khit Por. Where Khit Por was clear, language poetry was obtuse. Where Khit Por was authoritative, language poetry was democratic. Where Khit Por stated, language poetry implied. Myanmar poets found a freedom using language poetry. It was a way to avoid the claustrophobic sting of censorship. Language poetry requires readers to create their own meaning out of limitless subtexts, so the poet cannot be culpable for the meanings made of his poems. By writing language poetry, Myanmar poets were able to swerve any claims made about their intentions.

Some of Myanmar’s most prominent language poets are women, even though poetry was traditionally a male activity, with women often the subjects of poems but rarely the writers. In his articles, Lynn emphasised that language poetry was “a poetry of the brain” and eschews sentimentality – in essence, the poetry is free of traditional gender roles. This allowed female poets, such as Pandora and Eaindra, to become prominent in the movement. Indeed, the title of this feature comes from words written by Eaindra in her poem “Lullaby for a Night”.

“Art for no sake” scoffed the old school poets when they first read work by Zeyar Lynn and his gang. They said that the language poets, in their attempt to avoid anaemic government-sanctioned verse, went too far and divorced themselves from reality. But the works of these poets are not whimsical acts of denial but acts of craft. They resonate the poet’s intention on an intuitive level. They choose words that hint at an interpretation without making it concrete.

Myanmar’s language poets are radicals. By abdicating their authoritarian role as holder of a poem’s meaning, the language poets engage the reader in a democratic process of creation. Every reader has an equal right to create meaning. It’s a process that reflects, in the microcosm of the poem, a wish for Myanmar as a whole. Their critique of the government is shrill but impossible for censors to pin down. Their radicalism is found, as Pandora said, “reflected upon the leftover sunlight”.

* * *

Nathan Thompson is a poet from England who has taught poetry at university level. His work has been published in Errant, Firestorm and Small World. From next month, Southeast Asia Globe will begin working with Thompson on a regular showcase of the region’s finest poetry.

* * *

“Sling bag” by Zeyar Lynn

Translated by KoKo Thett and Vicky Bowman

Wherever he goes, in his sling bag

He carries his severed leg. If he has to shake hands,

He takes his severed leg out from the bag,

And touches it on the other person’s hand

As he says ‘Nice to meet you’

He must have gone through a lot of suffering

With that severed leg in his bag,

Though he still has his two legs intact.

When he needs reassurance, he’ll insert his right hand,

Like a dead hand, into the bag slung on his right shoulder,

To feel the sinews and greasy slime of the severed leg.

That’s how he recharges himself.

That’s how his pride is uplifted; his self-confidence restored.

The severed leg serves as his pillow when he sleeps.

The severed leg is placed on the dining table when he eats.

(Is he married? Let’s say he is.)

When he makes love to his wife,

The severed leg welds their two bodies together.

(Only then does he feel the hit, he says.)

The severed leg is his life, his past, his present and

His future, he says. ‘It’s truth’, he says.

‘It’s honesty’, he says.

‘It’s just him’, (says someone else).

Someone who claims to be a childhood friend.

He too always carries a sling bag.

* * *

“2010 the curvaceousness of Burmese poetry, poetics and an unknown” by Khin Aung Aye

the slice of bread buttered by moonlight on one side and pineapple jam on the other yes! the dermatological problem the shadows of the original stars banking must be this efficient and that easy as my urge to speak out spills over the petals are falling off in slow motion (read it) window/ table/ tools the hour hand travelling counterclockwise the umbrellas the peasant bamboo hats wheat as a replacement crop for poppy ‘wow, cowrie shells!’ the limelight stalking him claims ‘this is commissioner zhou enlai!’ in one song used papers carried off by a breeze into the streets smiles at me and says ‘i am still galloping’ in practice one has to be practical (even if one cannot be practically practical one must be practical) meanwhile he crashes into the scene the main actor has been wounded this part is not in the script he collapses framed in gold the golden picture of a golden beauty i have been nagging away i have been threatening as i am saying ‘don’t you see?’ the phone card the talisman hanging on my neck the sword swiftly impales me from chest to back nibbling on a potato chip i say ‘yes, sir’ am i not subdued by the blade am i not good for the blade goose bumps all over i kowtow just look after your goatee mindfulness just mindfulness will be useful for you all through the samsara engraved on the spectacles case is Inmind the filigreed teak partition masking a pair of my ears with my palms i am all ears Facebook appears on an elegantly straight bunch of hair drop by drop the way the newborn greets the world at the top of his lungs ‘U NGEE!’ how has he come up with how tediously tolerant they are he only he was capable of penning such lines but ‘’Limits/ are what any of us/ are inside of ‘’